Presence of mind

John Toll ASC / Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk

Presence of mind

John Toll ASC / Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk

BY: Ron Prince

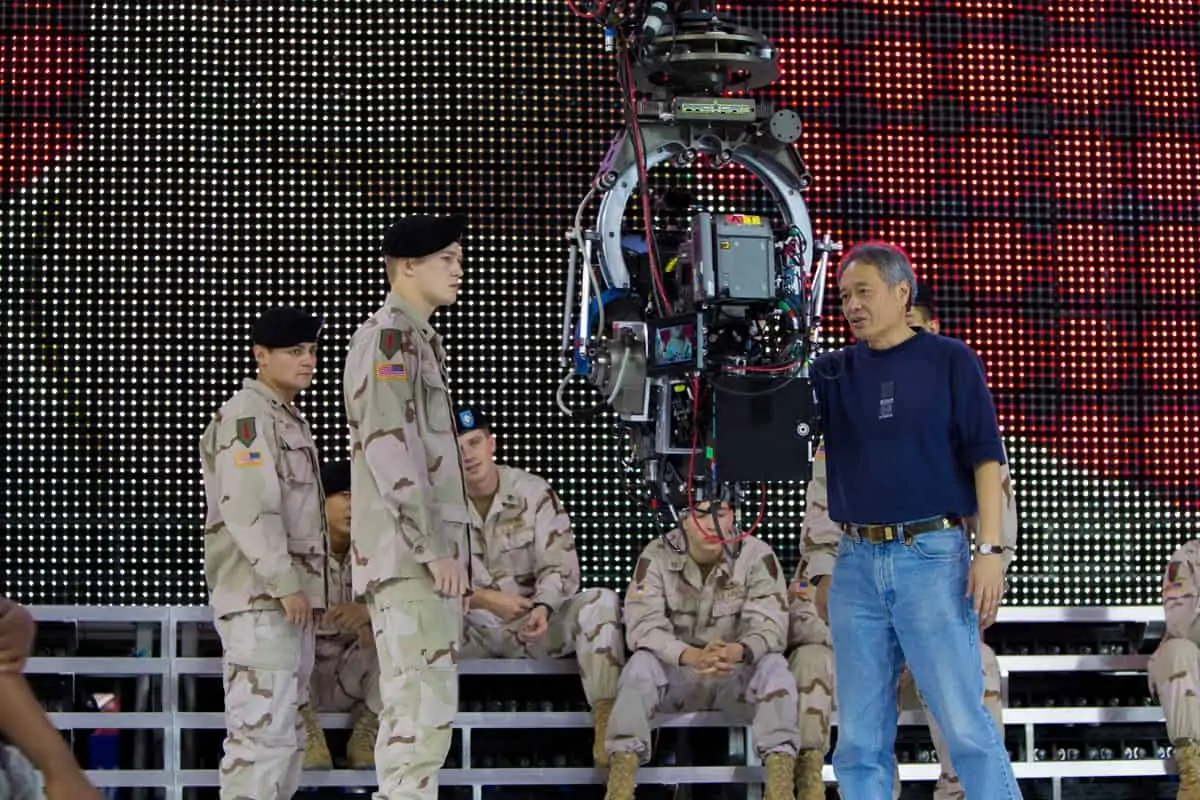

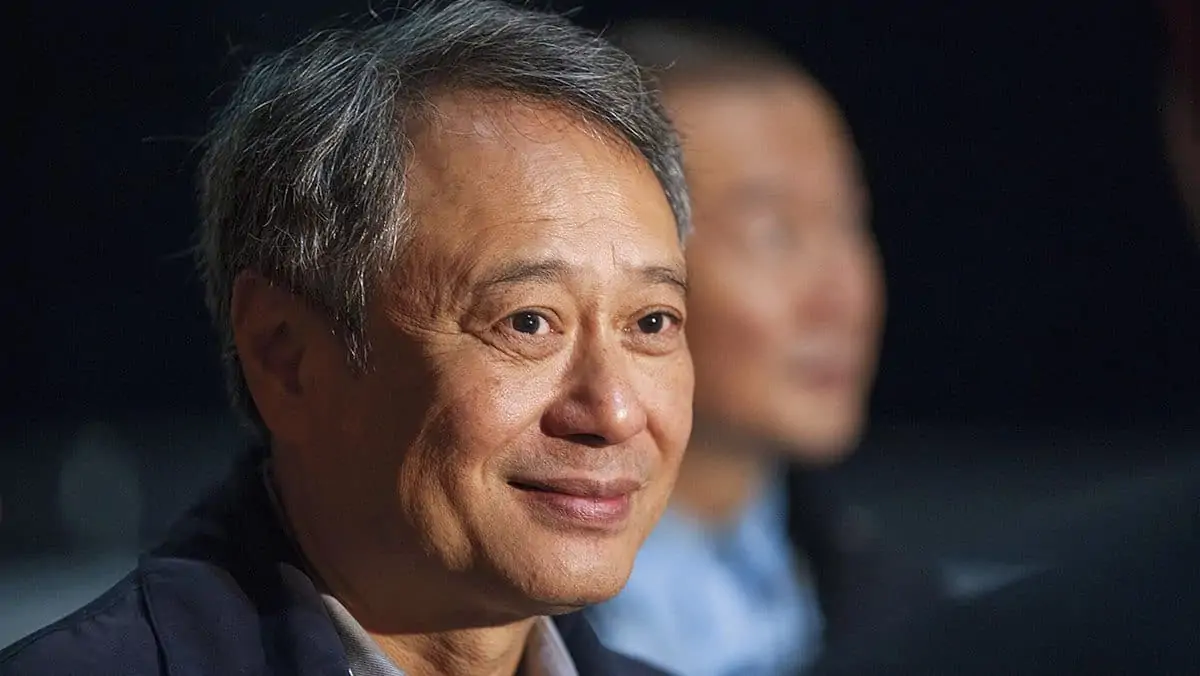

Three-time Academy Award-winning director Ang Lee harnessed his extraordinary powers to create extraordinary visual images for Sony Pictures’ Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk.

Using new camera technologies, shooting at 4K in 3D stereo, and at the ultra-high frame rate of 120fps for the first time in moviemaking history, Lee has created an immersive, digital experience that dramatises the realities of war in a way that has never been seen before.

Based on the acclaimed, best-selling novel of the same name by Ben Fountain, the $40m movie, produced by Film4/TriStar Productions, is told from the point-of-view of 19-year-old Billy Lynn (played by newcomer Joe Alwyn) who, after being co-opted into US military service, is sent to fight in Iraq. When Billy and his comrades in Bravo Squad survive a harrowing battle that receives broad news coverage, they are celebrated as heroes and brought temporarily back home by the Department of Defence for a promotional tour.

Culminating at the spectacular halftime show of a Thanksgiving Day American football game in Dallas, the movie reveals through flashbacks what really happened to the squad in battle – delivering a sharp contrast between the brutal realities of the war and America’s perceptions. Written by Jean-Christophe Castelli, the production also stars Joe Alwyn, Kristen Stewart, Garrett Hedlund, Vin Diesel, Steve Martin and Chris Tucker.

Double Oscar-winner John Toll ASC (Legends Of The Fall, 1994 and Braveheart, 1995) was chosen by Lee to oversee the cinematography on the production. After a ten-week prep period, principal photography began in the second week of April 2015, at locations in Georgia, including the Atlanta Georgia Dome, which doubled for the Dallas grid-iron stadium. The Iraq battle scenes were shot in Morocco. Shooting took place for 48 days in total.

Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk is the first feature ever to be shot at such a high frame rate. It is over twice the previous record set by Peter Jackson's 2012 The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey (shot 4K at 48fps) and, conveniently, it is five times the standard projection speed of 24fps.

After directing Life Of Pi (2012), Lee had intended his next project to be Thrilla In Manila, about the legendary 1975 heavyweight boxing match between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier. Wanting to broaden and enhance his use of technology in filmmaking, excited by what a higher frame rate might mean for the pugilistic sequences, and hoping to mitigate motion artefacts – such as blur and strobe effects during camera pans – Lee connected with filmmakers James Cameron and Douglas Trumbull, both proponents of higher frame rate production.

Inspired by them he shot a 60fps test for Thrilla In Manila, but when the production was postponed, Lee focussed his attentions on Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk. He invited Toll to shoot tests for the production at the higher frame rate of 120fps.

“Billy Lynn is a very personal story, and relied heavily on intimate character drama as well as action sequences. Ang wanted to depict the emotional journey of the soldiers, and to provide a new, immersive, realistic experience for audiences,” says Toll, who also adds, “although I had never met Ang before, I was hugely impressed by his knowledge, sheer talent and how he goes about doing his job with inspiring confidence.”

Curiosity is often a trademark of great cinematographers, and Toll undertook tests with five different camera bodies at 120fps, using different lens sets and rigs, to determine which combination was most appropriate to create the 120FPS, 4K, 3D imagery.

“While 120fps had a positive effect on undesirable image artefacts, it was also immediately apparent there was much greater clarity, more presence, depth and image detail at 120fps. It seemed to make the surface of the screen invisible, and gave visual access to characters like never before. It’s a bit like when you first wear glasses, and you get your 20/20 vision back. Additionally, 120fps, had the advantage that it could be easily converted down the line to the Hollywood release standard of 24fps, which was an important consideration for the worldwide release of the movie, as only a limited number are equipped to screen at 120fps/3D/4K.”

Considering their equipment options, and consulting with lead technical supervisor Ben Gervais, Toll and Lee selected Sony F65 4K-capable cameras and unfiltered ARRI Zeiss Master Primes, fitted to Stereotec mirror rigs.

“Billy Lynn was principally an A-camera shoot, with the B-camera used when we could,” says Toll. “We opted to shoot 1:1.85 aspect ratio, rather than go widescreen. The concept behind Billy Lynn did not need that sort of exaggerated help. Rather, we wanted to be inside the story, and to deliver a more honest and real presentation of the lead character and the drama. I did not filter the images in any way, as it would have been counterproductive to our reality.”

"There was much greater clarity, more presence, depth and image detail at 120fps. It seemed to make the surface of the screen invisible and gave visual access to characters like never before."

- John Toll ASC

The 3D camera rigs were assembled by Panavision in Los Angeles, a process which Toll describes as, “very technical, detailed and laborious – simply because no-one had ever put this particular combination of equipment together before. We were pretty much learning on-the-fly.”

Toll says that given the modest budget, and due to the complexity involved in shooting at a very high frame rate, the production could not afford to do many takes for any given scene.

“Ang knew that every shot would be difficult and at the same time be precious. So he meticulously planned in advance what he wanted to achieve. Before production began in the stadium, we spent five days working out the staging using stand-ins, and storyboarding every shot. By the time we came to shoot for real, we knew exactly what camera positions, angles and focal lengths we would need. Ang conducted regular morning meetings with key crew members to highlight things they needed to be alert on, and rehearsed every scene before we shot for real. We did exactly the same in Morocco for the battle scenes.

“I have never been better prepared on a movie, and reckon we had well over 70% of the shots nailed-down before we turned over. Ang knew the technology, what would make sense for the final image, and how to accomplish it. He revealed what a brilliant filmmaker he really is. He’s the real deal, and this is how we met the 48-day schedule.”

Toll’s camera, grip and electric crews on Billy Lynn included A-camera operator Kim Marks, supported by Chris Toll as A-camera first assistant, and Sal Alvarez as second assistant. B-camera operator was Greg Smith, with Clyde Bryan working as B-camera first assistant, and Jamie Pair as second assistant. Jarred Waldron was the gaffer, with Al Laverde the key grip, and Mike Moad the dolly/crane grip. Indy Saini performed DIT duties, with Kevin Wilson loading, and Jonathan Bennett and Clayton Smith undertaking digital utility tasks.

Shooting in stereo always brings with it the dual challenges of camera mobility and increased levels of illumination. While the Steroetec rigs are themselves lighter than most, the assembled 3D rigs for Billy Lynn still weighed-in at around 100lbs, and were voluminous items on-set. “There was no way we could just pick up those cameras and go grab a shot,” quips Toll.

Having in mind Lee’s request for Steadicam-style tracking shots in the stadium scenes, Toll turned to Herb Ault, veteran vehicle maker for motion picture productions, and his silent Grip Trix electric dolly vehicle, for a solution. The Grip Trix vehicle was adapted to fit a MovieBird telescopic crane, to which a remote Libra Head and a Stereotec 3D rig with cameras were attached.

“It was a more cumbersome way of doing it, with so many crew – three grips, two on the crane, the camera operator and the driver – all aboard the electric vehicle,” Toll says. “But due to their skills, and plenty of practice, we managed to create shots that are very similar to an operator wearing a Steadicam vest.”

To shoot the Iraq battle sequences, Lee eschewed the obvious tactic of moving cameras to create a sense of confusion. Instead he and Toll opted for quite the opposite, shooting from Billy Lynn's point-of-view to capture the realism and emotion of the scenes.

Indeed, both Lee and Toll were highly aware that performance is greatly affected by shooting at 120fps, calling for a more restrained acting style. Toll remarks that one of his favorite scenes in the movie is the salute to the US National Anthem, The Star Spangled Banner, in the Georgia Dome, featuring a tight close-up on Billy Lynn.

“The camera was incredibly close to Joe, and I imagine he could see his own reflection in the mirror on the rig,” he says. “Not a word is spoken in that minute-long scene, and there’s barely a change in Billy’s facial expression. Except that he begins to cry. The 120fps/3D/4K approach really made all of that emotion more readily accessible to the audience, and it’s incredibly moving and believable when you watch it.”

Due to the level of detail delivered by the high frame rate and high definition, Toll says the production team had to rethink everything. Shooting close-up shots, for example, meant the cast could wear only the lightest touches of cosmetics. Make-up artist Luisa Abel spent several months of preparation on skin tones, and used a silicone-based make-up instead of traditional cosmetics.

With the 3D mirror rigs and the high frame rate combining to reduce exposure levels by 3 1/4 stops, while also gaining one stop of exposure with the use of a 360-degree shutter, Toll addressed brightness issues in the stadium shots by various means – rating the camera at 800 or 1250 ASA, supplementing the ambient daylight coming through the translucent stadium roof with the stadium’s own lighting, adding powerful Helium lighting balloons fitted with mercury vapour bulbs to match the stadium lighting, as well as LED illumination on the football pitch.

“The aim, which we pretty much achieved, was to stay at T4 and have decent depth-of-field,” he says. “When you shoot in 2D, you would typically use shadow and contrast to create a sense of depth and volume. But shooting 3D, by definition, we got that depth and volume, and we actually wanted less contrast in the image, because we wanted to see the detail. So in that sense the process played into our hands.

“Of course the relentless, blasting of the sunlight in Morocco meant we needed much less lighting, perhaps a subtle fill here and there. I have to say that because of the pre-planning and the clever time-of day scheduling by Richard Styles, our first AD, we shot throughout the days in Morocco, just changing direction as the light changed to keep the visual constancy.”

Toll notes: “Although we beat the phrase to death, working on Billy Lynn was a truly collaborative experience – more collaborative than anything I have ever done before. To bring Ang’s vision to reality, Ben Gervais, our technical supervisor across the entire pre-production, production and post, was one of the key people involved. He proved absolutely brilliant with all aspects of the 3D production, workflow, editorial and grading.”

The DI grade on Billy Lynn was conducted by colourist Adam Inglis at a bespoke facility established by Gervais at Lee’s New York office. Due to working commitments, Toll was only able to attend the grade for one week, but says, “Adam and I spoke the same language. It was as if we had been working together for years, and he did a great job in delivering the final result.”

Toll concludes: “I have to say that until I was contacted by Ang, I had never been particularly drawn to 3D, and had never shot any 3D material whatsoever. But my experience on Billy Lynn was one of pure excitement, and it was a genuine thrill to be on this voyage of discovery. The possibilities for visual storytelling have expanded tremendously with Ang’s 120fps/3D/4K approach.”

Comment / April Sotomayor, head of industry sustainability, BAFTA Albert