Summit to think about

Letter from America / Richard Crudo ASC

Summit to think about

Letter from America / Richard Crudo ASC

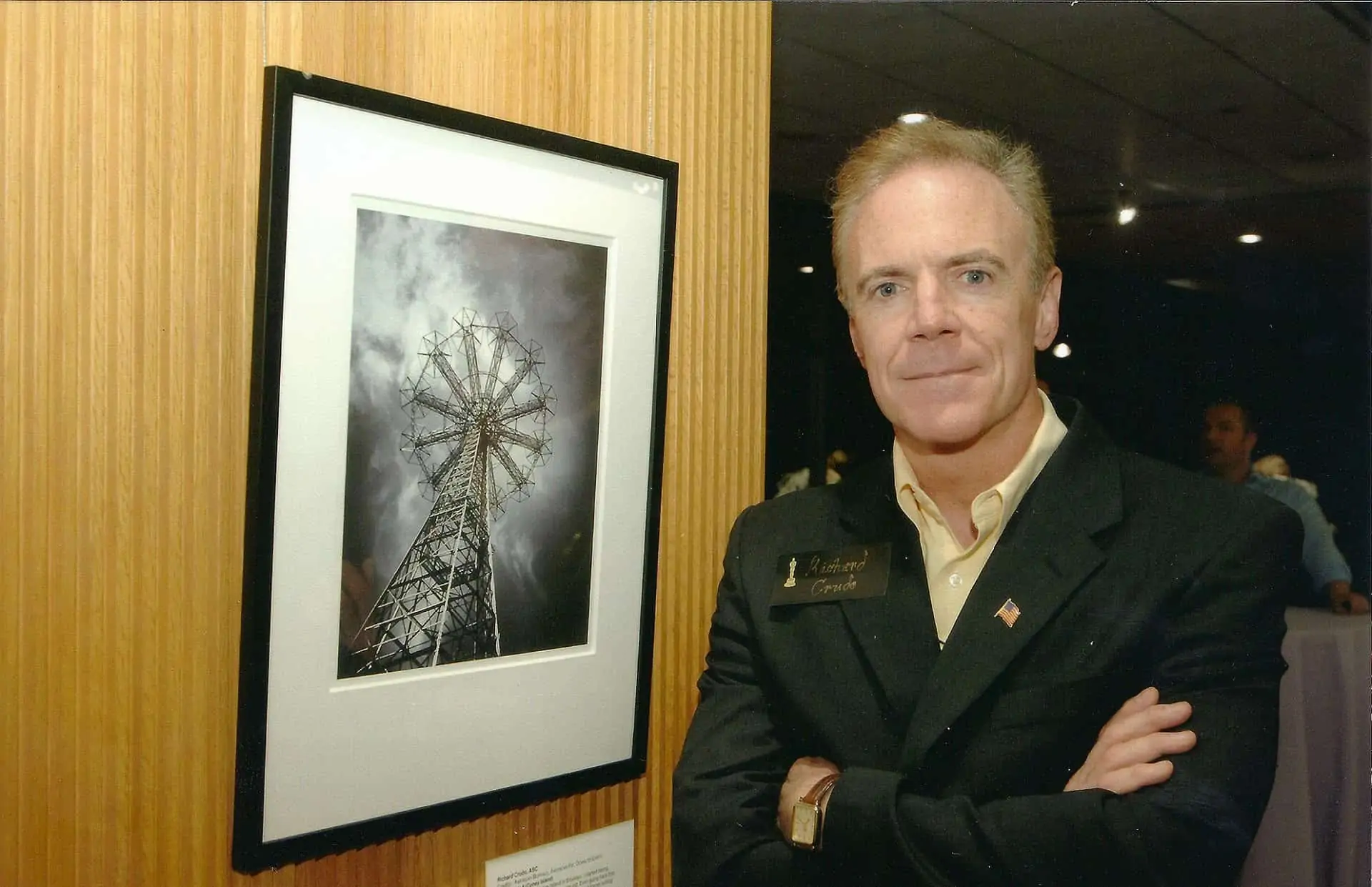

Outgoing ASC president Richard Crudo ASC reflects on the big issues debated during the 2016 International Cinematography Summit in Los Angeles.

In addition to the many good things that can be said about cinematographers, people often lose sight of the fact that we're also the most generous in how we regard our colleagues. No other discipline in the motion picture industry can make a remotely similar claim to such solidarity, affection and respect within the ranks. Anyone who has had the good fortune to attend a gathering of our number will instantly recognise the special bond. Cinematographers have always been known as the most passionate artists in the business; it's no surprise that our shared understanding of the “how” and “why” of what we do translates so easily on a social level as well.

And this is precisely why we regularly meet in our home countries in an effort to protect and expand our interests. Seeking to bridge the geographical distance, early this past June, the ASC hosted the second International Cinematography Summit at our Clubhouse in Hollywood. It was attended by representatives of more than thirty cinematography societies from around the world for the purpose of increasing communication and interaction surrounding the artistic and technical changes that are affecting our craft. The first summit was held in 2011 and was a huge success; the results this time were even better.

Standardisation of emerging technologies, educating the next generation, archival concerns, future trends - these issues are at the forefront for all of us, regardless of where we live or work. Beyond those however, a few critical items seemed to permeate the zeitgeist.

One concerned an aspect of artist's rights. It's scary to think that at this late date we're still hearing reports about cinematographers being blocked from supervising the finish of their work in the DI suite. Does discouraging or altogether barring the cinematographer from placing the final touches save money or time? Example after example has proven the opposite to be true. Equally troublesome, artistic integrity is compromised every time the original intent developed by the director and cinematographer is cast aside. Since we're hired for our taste and expertise – which are generously proffered at every point in the process, by the way – you really have to wonder what's going through someone's head when they choose the exclusionary route. Compounding the insult, throughout the world we are rarely paid for our post-production labour.

Short of a binding, right-of-authorship agreement – which I assure you will never be enacted in the United States – we're pretty much left to our own devices in this respect. Our employers are aware of the great commitment we bring to the job and many of them are all too eager to use that against us. Right now our only recourse is to develop strong relationships early-on with directors and producers that will serve to protect us when necessary. The irony is that the smart ones understand how important our contribution is and generally insist that we supervise the DI. Problems usually emerge only when the uninformed are in control, and sadly there are enough of those running around the industry to fill the London O2. Hopefully the feelings stirred at the International Cinematography Summit will spread some desperately needed knowledge and lead to an improved situation.

A second topic that drew a great deal of momentum was the problem of excessive working hours. This has become a nearly universal policy that is by nature insidious; on the surface it doesn't seem dangerous, but it is. Speaking from my own considerable experience, it's a miracle that on innumerable occasions the extreme exhaustion experienced by myself and my fellow crewmembers hasn't led to disastrous consequences.

"As Directors of Photography, our responsibility is to the visual image as well as the protection of our crew. The continuing and expanding practice of working extreme hours seriously compromises both the quality of our work and the health and safety of others. It is our obligation to oppose a situation that threatens the well being of every member of the crew."

When the late ASC legend Conrad Hall expressed this sentiment in 2002, he had just endured (survived, is a better term) an arduous – but not particularly uncommon – schedule on the feature Road To Perdition (2002). He returned home with a desire to alert the industry and incite reform of a mindset, which had taken an enormous toll on his health. For the first time, he put forth the notion that excessive hours had become a type of officially sanctioned abuse. In 1997 Los Angeles-based assistant cameraman Brent Hershman was killed while driving home from a shoot in a sleep-deprived state. Countless others continue to avoid a similar fate merely by luck or the hand of God. It remains a black mark on the industry that no substantive action has been taken to reign-in the thinking that leads to the working under these onerous conditions.

The international assembly agreed: this needs to change and the sooner the better. As always, the “how” part is the difficult part and no course of action was determined. Perhaps it's just as well that we continue to chip away little-by-little as we engage the battle to maintain our dignity.

Nonetheless, the summit concluded with a spirit of accomplishment and optimism. It was gratifying to witness so many cinematographers from so many parts of the world acting so intently upon the challenges of our day. It came as no surprise, though. When you think about what we do and what we all represent, it goes to show you that once again: that's just who we are.

Richard Crudo ASC

Past President

American Society Of Cinematographers