Who's Afraid Of Red, Green and Blue?

Vittorio Storaro AIC ASC / Wonder Wheel

Who's Afraid Of Red, Green and Blue?

Vittorio Storaro AIC ASC / Wonder Wheel

By the master himself, triple Oscar-winning cinematographer, Vittorio Storaro AIC ASC, shares his experiences of shooting Woody Allen’s Wonder Wheel digitally, and offers more sage advice for up-and-coming cinematographers.

“I see in colours the effort of matter to become light” (Plato, Greek philosopher, 427–347 BC)

"Red has an expiatory, protective function" (Lia Luzzato/Renata Pompas, Italian scholars)

"Green is a moral colour" (J. M. Vincent, American Scholar, 1906–1987)

"Blue, the king of colours, comforts the heart" (Guillaume de Machaut, French poet,1300–1377)

I think I heard someone say: “Look at what those two ‘young visionaries’ of the cinematic image, Woody Allen and Vittorio Storaro – the one with his writing with words, the other with his writing with light – are up to on Wonder Wheel, their second film together. They only just entered the world of digital cinema with their first movie together Café Society!”

Indeed, looking back, Woody and I seemed quite happy in our classic world of celluloid, so familiar with the mysterious filmed image and the way it is revealed after it has been conceived, as if it were being born. Matter – through the physical elements of the camera, lenses, film stock, and the language of light – was transformed into visible energy, into an image. With that image all doubts, uncertainties and questions vanished, and we revelled in the wonder of cinema. It was a terrific thrill that we experienced every time, especially at the first screening of a new film.

By constantly imagining, thinking and dreaming, it is possible to materialise the feelings, emotions and filmic intuitions that both the director and the cinematographer – each in their own “space” and in their own imaginations – had in mind and wanted to see on the screen.

As I recall, the filmed image was viewed with the trepidation that precedes a discovery. Despite our knowledge of its history, of technique, of the mysterious nature of the camera obscura, etc., we were accustomed to, and had developed and matured with, a system that could be improved, that was not finite, but infinite.

The initial education regarding photographic and cinematic images, the knowledge, and the distinctly pictorial style until around the 1970s, had led the film industry to believe that B&W was most appropriate for dramatic films, with colour for comedies, Westerns and musicals. Shade, they thought, was not captured well by colour.

Then, probably with the arrival of colour television, they insisted on films being made in colour for the benefit of the international film industry. The public wanted colour, so B&W appeared to be a thing of the past. On the majority of productions, most directors and cinematographers preferred to stay with the monochromatic style, with tone on tone, nearly always imagining the beautiful look of the daguerreotype – a warm ochre/orange tonality, very maternal, as some psychoanalysts would say. Bold colour images were not considered creative, refined or artistic, and many people still see it that way.

"Colours are the children of light and darkness" (Leonardo da Vinci, Italian genius, 1452–1519)

"Colour has an amazingly variegated, expressive and harmonious vocabulary"(Alexander Blok, Russian poet, 1880–1921)

I instead rebelled against the classic education, and ventured excitedly into the world of colour, although I was unaware of its various meanings during the years I studied photography and cinematography. I gradually encountered the great Italian masters such as Leonardo, Michelangelo and Caravaggio. In my early films, my chromatic inspirations sprang from emotion, an innate instinct, and being in love with the image.

Looking back to the 1980s and early ‘90s, Woody and I drew on the cinema of the past: Woody with iconic cinematographers like Gordon Willis and Carlo Di Palma.

Myself with iconic directors like Bernardo Bertolucci and Francis Coppola on films such as Il Conformista and Apocalypse Now.

Then someone invented the digital image, and in the last five years the film industry has changed almost completely. So when Woody asked me to collaborate on Café Society I read the screenplay, which gave me various figurative ideas for the different stages of the story. These I based on the works of painters like Georgia O'Keeffe and Tamara de Lempicka in contrast to those of Otto Dix and Edward Hopper. Well aware that progress can be slowed down or speeded-up, but never stopped, we decided to enter the digital world together.

For Café Society I proposed to Woody two very different worlds for the Bronx and Hollywood in the 1930s/40s, and he completely agreed. He immediately loved the idea of digital and the colour variations that accompanied the story in the various stages of its development.

In actual fact, digital cinema was not something new for us, but rather a confluence of the individual paths we had trodden to that point. Woody forever in in New York, New York, New York. Me in Sienna during childhood, Rome for my studies, Parma on films with Bazzoni and Bertolucci, and L'Aquila where I taught at the Accademia dell’Immagine. Woody with all the nostalgic evocations, the amarcord/remembrances of his New York in tow. Me with a weighty baggage of images, which were often markedly pictorial, since I love the Renaissance, and am obsessed with Caravaggio and his constant conflict between light and shade. Woody with his monochromatic, desaturated tones. Me with my powerful chromatic emotions deriving from my studies on Isaac Newton, and Goethe and the symbolism, dramaturgy and physiology of colour.

I have always thought that no matter what profession we practice, we inevitably seek to recognise our own expressive potential, to come up with answers to our own questions. So I was very happy when I initially found some figurative hooks in the first version of the screenplay of Wonder Wheel, which would allow me to express myself through my chromatic tones and my visual vocabulary in Woody’s story.

I was faced with a story that at first seems tranquil on the surface, but has a variety of conflicts going-on underneath. It is a story about an American family set in 1950 on Coney Island and an amusement park in Brooklyn, with very long scenes full of dialogue between the various individuals.

In my ignorance I knew nothing about Coney Island. I was afraid that I would not be able to come up with a pivotal, figurative idea for the visual. I confessed all this to Woody, who immediately put my mind at rest by assuring me that we would come up with a specific vision of the production.

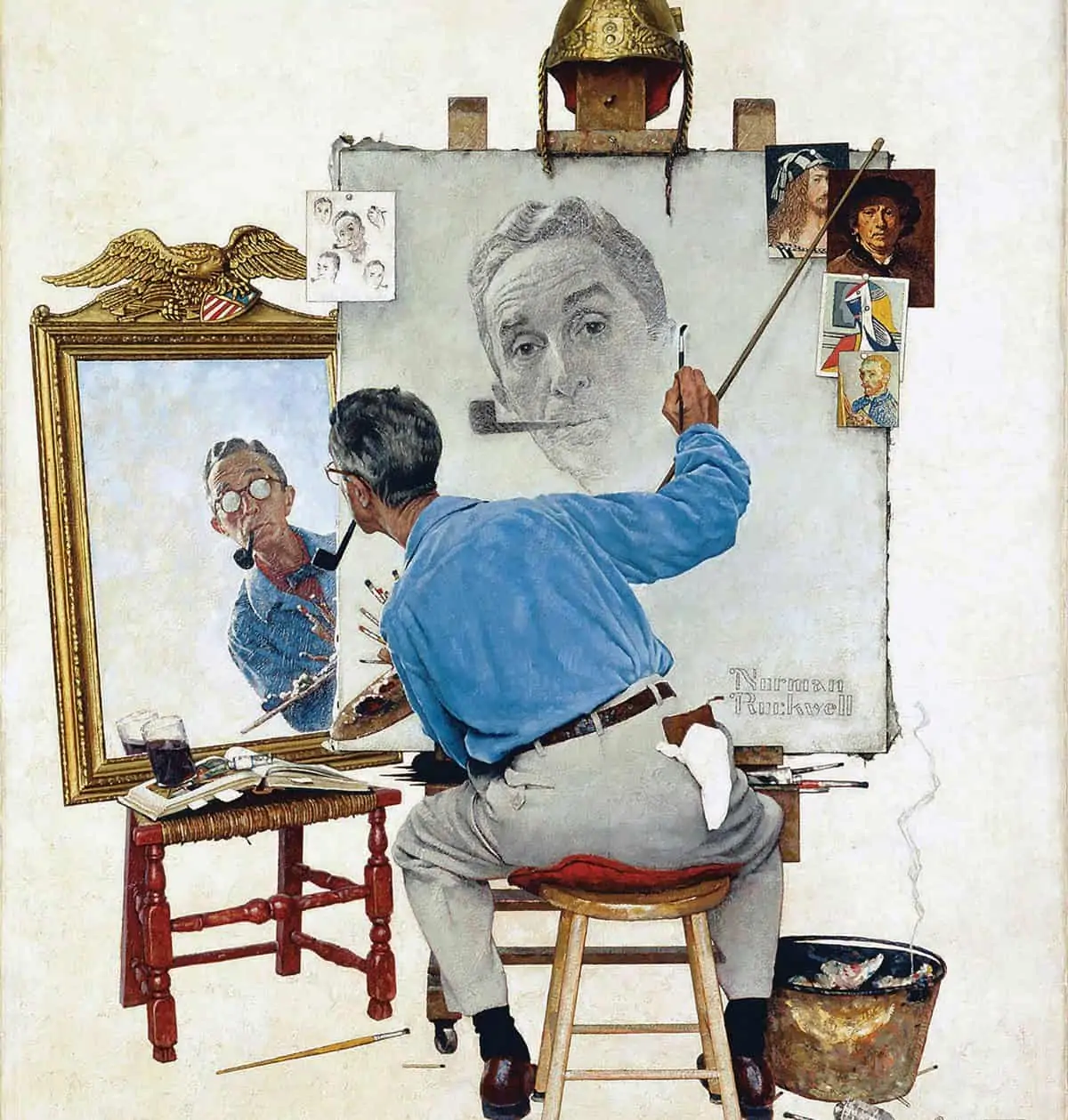

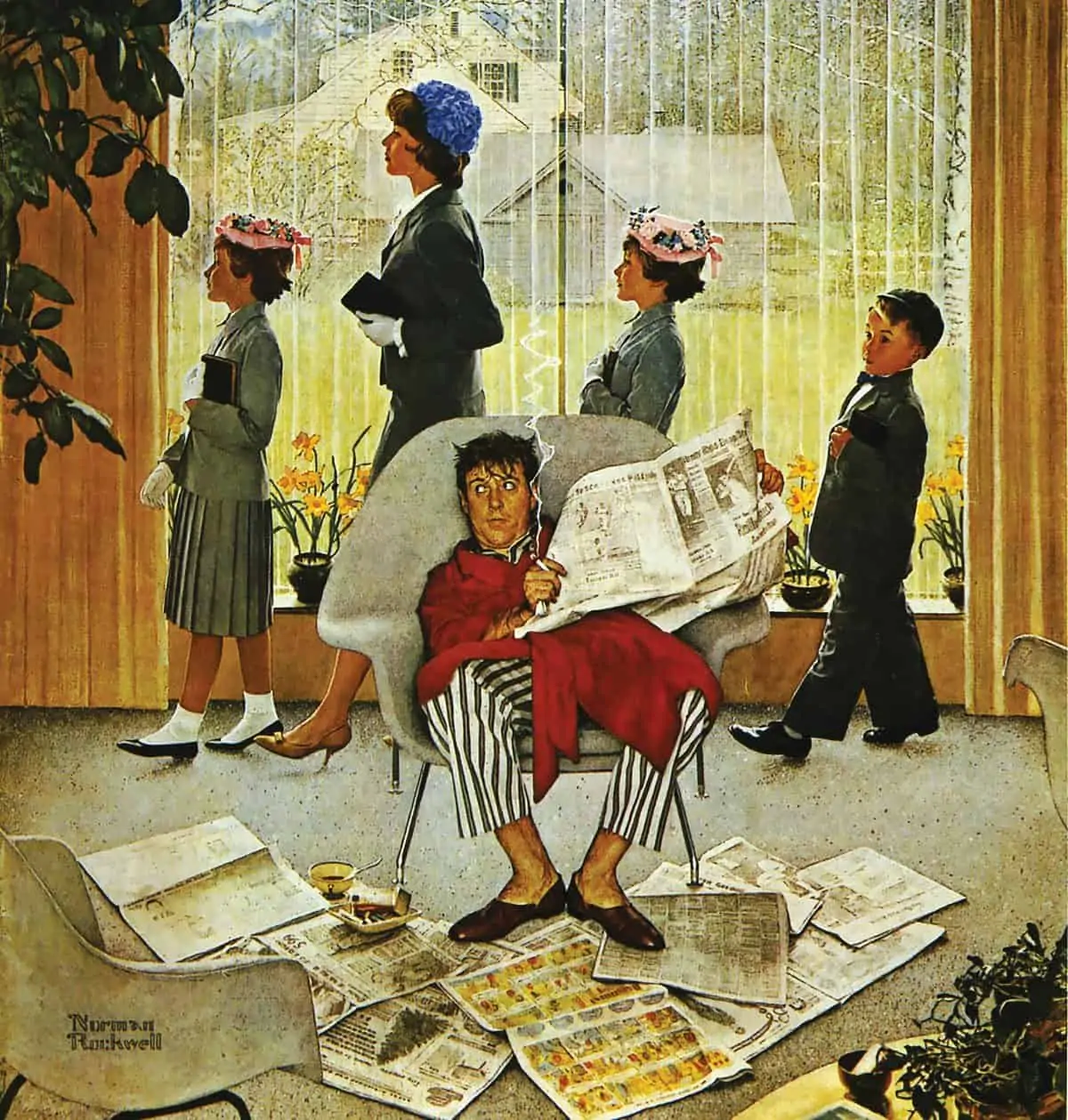

And then the idea of a superficially serene world, in which life’s problems later surface, suddenly brought to mind Norman Rockwell’s painting of the post-war period: a vision of life that was all sweetness and light on the outside, but conflicted at its heart.

When I arrived in New York, we began the scouts – we being: myself, Woody, the production designer Santo Loquasto, and the co-producer Helen Robin – and when I discovered Coney Island, I understood its visual possibilities right away.

The characters in the story lived with the fantastic world of the amusement park outside their windows, and with their family conflicts inside their apartment. The actors – Ginny (Kate Winslet), Mickey (Justin Timberlake), Carolina (Juno Temple), and Humpty (Jim Belushi) – made up a great cast and truly completed the whole picture. Certainly their great acting allowed us to realise a specific visual style, in the long scenes of dialogue, which were very complex but became efficient on various levels: the luminosity, composition and rhythm of the images.

My specific vision for the cinematography was inspired by various painters of the period, especially Reginald Marsh, one of the many who depicted the fantasy world of Coney Island.

Then I had an even more important idea to visualise the story. Ginny and Carolina’s worlds are in conflict, because they are both in love with Mickey. It made me think of applying the Physiology Of Colour theory and how colours are perceived by humans for dramatic effect.

Human beings not only receive light through their eyes, but all over their bodies. In fact, we are like a sensitive photographic plate. When visible energy and its colours strike our body, they modify our metabolism and blood pressure according to their intensity and chromatic frequency, creating unconscious emotions.

Woody immediately saw the visual potential of the story told according to this specific vision, and being no longer afraid of Red, Green and Blue he helped, indeed spurred me, to formulate a figurative structure, a cinematographic concept that divided the two worlds between fantasy and reality: Ginny’s world, experienced through the warm tonalities of an orange sunset, and Carolina’s world, experienced through the cold tonalities of a blue dusk.

This is how we created a palette of lights and colours that accentuated the variations in the dialogue by reflecting the character’s emotions.

When I shared my theories with production designer Santo Loquasto and costume designer Suzy Benzinger, in full agreement, we started to create a specific vision of the film together. This is what should always happen: each film should have a special vision, in keeping with a particular story.

"Red has represented our existential dawn since human life began. It increases blood flow, muscular tension, and pulse rate. It signals the Positive, and is the flame of the human spirit. It is the colour of the past" (Vittorio Storaro)

So with the help of: different scenographic and costume elements; various filters in front of the Cooke S4 lenses; two Sony F65 4K 16-bit colour cameras, prepared for image composition with an aspect ratio of 2:1 at Panavision by Chris Konash and Steve Will; assistants Bobby Mancuso and Beka Venezia; Rosco gels on the Cinelease /Iride projectors controlled by the lighting console; the collaboration of gaffer Steve Ramsey and key grip Bill Weberg; and especially through natural light of the afternoon/sunset and dusk/evening, and dividing the spectrum into two different emotive tonalities, I was able to write the story of Wonder Wheel with light.

Thanks to Isaac Newton’s science and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Theory Of Colours, and their palette of Red–Orange–Yellow–Green–Blue–Indigo–Violet, I had the “Seven” colours at my disposal, but I used the language of colours, basically extracting only two. Orange and Blue.

No one should be afraid of colour. We have to get to know it and its expressive potentialities. By creating harmony or conflict between the three primary colours Red/Green/Blue, and their three complementary colours Cyan/Magenta/Yellow, we can convey visual emotions to the audience, in the same way that words convey sensations in literature, and notes in music.

I think knowledge of the symbolism, dramaturgy and the physiology of colour are fundamental, particularly in the digital age. This knowledge allows us to use colour with greater awareness in the visual arts, and especially in cinema.

Today, the cinematic image no longer has the mystery it once had, and a knowledge of the meanings of light and colours is both indispensable and essential – to suggest, to create and, if necessary, to modify the colour images that the monitor shows us on the set, in front of everyone.

In digital cinema, the arrival of the HDR (High Dynamic Range) system – that offers enhanced colour saturation (much in demand by young audiences) and produces bright, high-contrast, colour-saturated images suitable for action movies and spectacular special visual effects – may lead us to believe that this kind of vision is not appropriate for films about human feelings or for dramatic stories.

But actually, it can be a great help if we use the dramaturgy of colour with awareness. I know that Amazon will request the HDR version of the film Wonder Wheel and I'm happy that I prepared it, because it is in line with the vision of the story.

"Green is positioned in the middle of the spectrum. It links the two worlds of the 'beginning' and 'end', of light and darkness. It divides materiality from the destiny of spirituality. It is the colour of the Soul, and represents knowledge" (Vittorio Storaro)

The Univisium 2:1 composition; the rhythm of the images captured by the digital cameras, guided by operator Will Arnot; the quality controls carried out by DIT Simone d'Arcangelo; and the close examination of those images for the rushes, by colourist Anthony Raffaele at Technicolor PostWorks in New York, were fundamental for me in envisaging, creating and perfecting the figurative quality of Wonder Wheel during the entire period of preparation and production.

With the authenticity of some additional images outside the windows of the family’s apartment, created by the visual effects department at Brainstorm, and VFX supervisors Rich Friedlander and Eran Dinur, we completed the harmony between the visual work and the dramaturgy of Woody’s original screenplay.

I have always thought that today’s sensors, and the filmstocks that came before them, have always been and will always be more sensitive than technicians tell us. They are actually able to capture the emotions of the whole crew that participate in making a film. And when this is done in creative harmony there is a strong probability that the film will turn out well, that it will be a good film.

"Blue is the colour of thought and intuition; it is conducive to keen intelligence. Of a spiritual nature, it has something superior to the human being itself. Psychologically speaking, it increases a tendency toward sensibility. Its movement is centrifugal; it tends to recede from the eye. Blue is the colour of intelligence and the future" (Vittorio Storaro)

Whilst we were wrapping the film, I heard someone say: “If Woody and Vittorio have a bit of a future together, who knows what those two will do next?”