Into the unknown

Documentary cinematographer Tim Cragg focuses on the breathtaking world of freediving for Laura McGann’s gripping documentary.

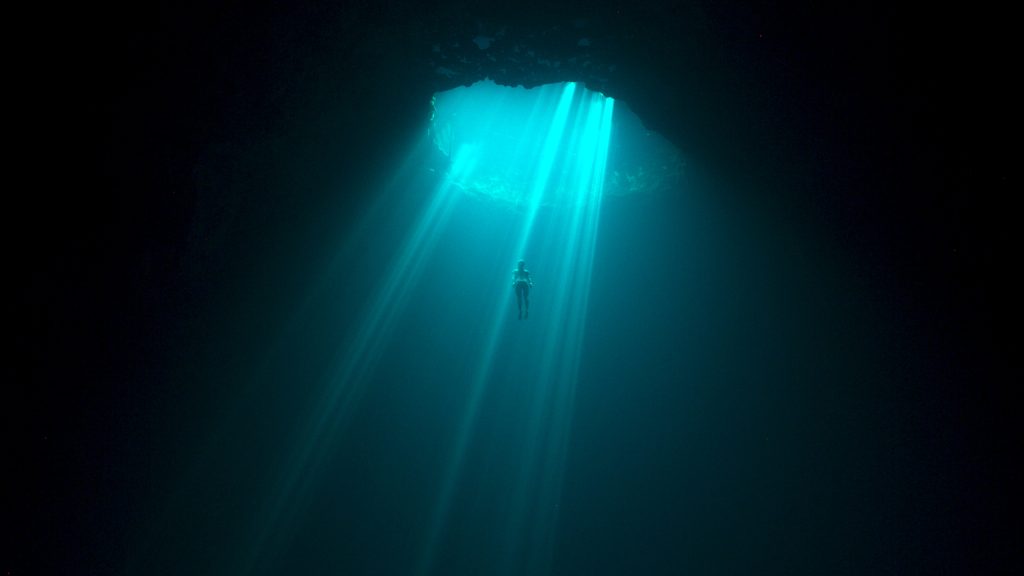

It’s not often that a film comes along that makes you – quite literally – hold your breath. But in the opening scenes of The Deepest Breath, watching champion freediver Alessia Zecchini descend to what she describes as “the last quiet place on Earth” without any breathing apparatus feels suffocating.

Laura McGann’s documentary, which had its UK premiere at Sheffield DocFest, follows Zecchini and her safety diver and friend, Stephen Keenan, on her attempt to break another world record. Blending archive footage from Zecchini’s flourishing career with interviews with family and friends, it paints a compelling picture of a life lived beyond limits.

McGann looked to BAFTA Award-winning cinematographer Tim Cragg to lens Zecchini and Keenan’s story. Cragg, who has shot feature documentaries for Netflix, the BBC, HBO and Amazon, began his career in 1989 as an editor, before transitioning into shooting in the early ‘90s. “I was lucky – I just found an angle that did well,” he says. “I had an old 16mm Aaton camera and that was the start.”

He is also a prolific stills photographer, enjoying shooting on film. “I like the idea of controlling the image and seeing the world through a frame,” he explains. “What I like about photography is the purity of it. It’s easy compared to cinematography in that you don’t have all the people around you – it’s the freedom without the massive teams.”

With an in-demand eye for a shot, Cragg admits he is offered around five projects a week – so what stood out about The Deepest Breath? “I choose projects that have an expectation to do well and have stories that I’m attracted to, and then try and mix those up. This film was made through the pandemic, when everyone was feeling restricted at home, so we wanted to bring the outside world to our audience because at that stage, the outside world didn’t exist.”

Interestingly, it wasn’t Cragg’s first foray into freediving – he’d worked on a sequence on the topic for an episode of BBC’s The Human Body.

Although he had not worked with McGann before, the DP was familiar with Revolutions, her documentary on Ireland’s roller derby scene, and was intrigued by the subject of her newest project. “Sher was a joy to work with – talented, humble, open to suggestions. Really impressive,” he adds.

McGann wanted Cragg to bring sunlight into the film in his lensing. “That was something extremely new to me – most of what I shoot is very dark, very lit and film noir-ish, as I do a lot of true crime” he say. “She wanted the interviews to be bright and almost hopeful, and to have windows behind with sunlight pouring in. It would almost be like we were at the beach with these people and they’d just been doing their dive, and we’d wandered in in a very casual way to chat to them.”

In terms of references, the DP recalls: “Laura and I both loved the large-scale black-and-white seascapes of the Japanese photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto and the work of photographer Corey Arnold who captured the relationship between human beings and the ocean in his images on Fish-Work: The Bering Sea.”

The documentary were captured on two RED Geminis, coupled with Cooke 2X Anamorphics, from London’s Big Eye Rentals. An initial worry with shooting anamorphic was, would it be too much of a clash when used alongside the archive footage? Ultimately, Cragg and McGann opted for the more cinematic look that the lenses offered.

Filming for the project, which took place over eight months in 2020, was a real globe-trotting endeavour, with trips to Egypt, the Bahamas and the south of France. Faced with the double whammy of COVID restrictions and remote locations, the filmmakers sometimes needed to hire private planes to get their desired shots.

When shooting the interviews, Cragg and McGann were conscious of how they framed the speakers. “When we looked at the main character, Alicia, we wanted to make sure we photographed her in a different way,” the DP explains. “She would be singularly framed in the middle of a frame and extremely close, so it would feel like you’re in her world. I love it when you’re so close – there’s nowhere to go and you see every single muscle… It’s not just the words, we start reading all those details and those tensions. It’s very powerful.”

Cragg’s lighting package for the interviews included Aputure’s Nova P600c, LS 300s and LS60s. “I like the Aputure kit because I can operate them all off an iPad – I can control every single light.”

With the subaqueous material – shot by underwater cinematographer Julie Gautier and Florian Fischer – the filmmakers’ aim was to create an almost space film-like environment, highlighting the vastness of the ocean. “The underwater scenes were where we could really let the lid off and allow the breathing and the elegance to happen – Julie was the perfect person for that,” says Cragg.

Other key collaborators were editor Julian Hart, who Cragg credits for helping to build the film’s ever-increasing tension, and Molinare’s Vicki Matich, who worked on the grade. “We wanted it to feel hopeful, with sunshine pouring in, and she did a great job at that,” the DP adds.

How does Cragg see the role of the documentary DP compared to its narrative counterpart? “As a [documentary] DP, what you’re bringing to the project isn’t just the look of the film, but making sure the contributors felt comfortable,” he muses. “All the contributors that we filmed got upset at some point and everyone in the crew was brought to tears at points, because it’s such a powerful love story. We were very much part of allowing a space for people to feel safe to talk. The craft that you bring to a documentary can not necessarily be an aesthetic one but something that protects the director, supports them and gives them the confidence and allows everybody a space to be their best. Sometimes you make sacrifices for that – sometimes the light would suddenly change outside and sometimes you’ve got to go with that, whereas on things that are more controlled, you’d stop and do another take. But if someone’s baring their heart and bawling their eyes out and something goes wrong, you live with it.”

The Deepest Breath is released on Netflix on 19 July.