Face Off

Rob Hardy BSC / Ex Machina

Face Off

Rob Hardy BSC / Ex Machina

BY: Ron Prince

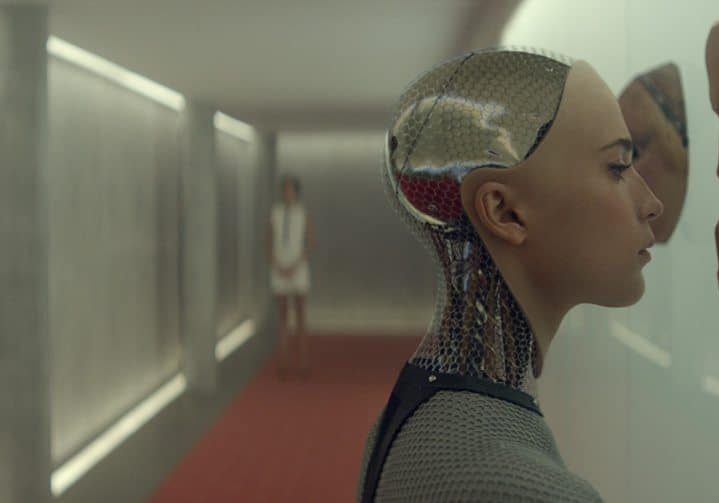

The extraordinary British sci-fi thriller Ex Machina is set in one central location and has just three speaking parts. Its premise is based on the central theme of what it is to be human - to determine whether a machine might experience or develop a sense of consciousness comparable to our own.

In many ways serves as a companion piece to both Her (2013, DP Hoyte Van Hoytema) and Under The Skin (2013, DP Dan Landin), which each address similar themes in their own invigorating and original ways.

Written and directed by Alex Garland, making his directorial debut, the movie stars Domhnall Gleeson as Caleb, an up-and-coming computer programmer who wins a contest to meet with Nathan, played by Oscar Isaac, the reclusive internet genius and CEO of Bluebook, a large search engine company. However, when he arrives at the Alaskan underground laboratory, Caleb discovers he’s part of an experiment to test the artificial intelligence of an android, named Ava, performed by Alicia Vikander.

Is she still a machine, we wonder? Or are we witnessing something as alive and self-aware as any human? The movie taps directly into modern-day anxieties about technology and our potential obsolescence. It's a topical subject, as Professor Stephen Hawking evoked explicitly last December when he spoke of his fear that “the development of full, artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race." However, unlike Hawking and even Stanley Kubrick, Garland claims he has no fear of technology – he’s all in favour of robots and whatever their unstoppable destiny may hold, which adds an inherent twist to the proceedings.

That said, the dangers this implies about the downfall of man are foreboding, unnerving and have been strikingly rendered for the big screen at 4K by Rob Hardy BSC.

Ex Machina was shot over the course of six weeks on two large, self-contained sets forming a warren of rooms, inside dual stages at Pinewood. The movie also shot in Norway, with exteriors doubling for Alaska that serve to highlight the freedom Ava appears to be longing for.

The £16m DNA Films/Film4 production includes Andrew Macdonald, Allon Reich, Scott Rudin, and Tessa Ross amongst the producers. By dint of coincidence, Ex Machina goes on general release in the UK on the same day as Testament Of Youth, the first instalment of Vera Brittain’s memoir, covering 1900–1925, which Hardy also lensed at 4K. Ron Prince caught up with Hardy over Skype to discover more about his creative approach and working regime on the movie.

What intrigued you about Ex Machina?

RH: A number of things. The chance to work with Alex was top of the list, and Ex Machina was simply the most original and intelligent script I’d read in years. I had read Alex’s script for Never Let Me Go (2010) and, although I didn’t shoot that movie, I thought it was so beautifully written. Ex Machina was the same. I devoured it, as if it were a fantastic novella. It had a different edge – questioning your perception of the world around you. It asks what is human? What isn’t human? What it is to be human? For a British script to tackle these themes with such originality is quite an extraordinary thing to be part of. Recently, it seems, there has been a trend towards exploring notions of what it is to be human based on already existing historical figures in both art and science, but Ex Machina does something utterly different: it uses original characters that ask new questions, and faces the future head-on, rather than relying on the dramatic safety net of history. From a script point of view this is an unusually bold move. So all credit to Alex and of course Scott Rudin, Tessa Ross, DNA and Universal for seeing the truth in that.

From a practical point of view, it was different to the location-based dramas I’ve shot such as Boy-A (2007) and Red Riding: In The Year Of Our Lord 1974 (2009). The science-fiction framework and the enclosed setting presented new and exciting challenges to me. So when Alex contacted me, I jumped at the chance to work on the movie.

What was the nature of you creative conversations with Alex the director?

RH: Alex and I had a sort of on-going, evolving conversation throughout pre-production that revolved around the idea of how to turn the contained space of the labyrinthine set into something quite elevated and epic, and also about Ava, the AI centrepiece of the movie, and how she develops into becoming more and more human.

Our visual manifesto for the movie came from a true collaborative effort. It was as if the film’s looks were creating themselves by a strange form of visual osmosis. Let me explain. During the build, I spent every day at Pinewood, working with Alex, liaising with the art department, as well as Movietech who supplied the camera package. The actors came down to the set too. It felt like a family in many respects. We could all get a feel of the sets, try out the emotional choreography of the scenes and discover how the characters would perform there – all as the sets were being built. Things fell together for us. Our conversations went on constantly, about the functional aspects of the set design, as well as the emotional centres of each scene. To have the two aspects run side-by-side in that way was a new thing for me. I normally do the script work first and then the location and tech recces, and then start. It was an extremely organic and honest process. Through a constant dialogue based on trust and a common admiration for the material, all the usual ego’s were stripped bare and we managed to bypass all the bullshit that can sometimes stack up, and just get on with making the best possible film we could as a single perfectly functioning unit.

What creative references did you research?

RH: With a science fiction film, that’s shot on a set, with counterpoints of the natural world, and a touch of a love story too, you just can’t avoid thinking of classic movies. But I deliberately didn’t talk about them nor even allow them into my thinking. This was such new territory for me, and I wanted to bring a new interpretation to it. I recall that Alex and I spoke about the photographic work of Saul Leiter early-on during our very first interview, and discussed the abstracted forms developed by Malevich and the painterly qualities and innovative compositions of their work that might form touchstones for the vision of Ex Machina, but that was about it.

How did you decode the Aspect ratio and decide on the cameras?

RH: We didn’t ever have an aspect ratio conversation. We just assumed from the outset that we would shoot as 2.35:1 to capture the internal concrete spaces of the set, and the actors, and the external landscapes of the glaciers and forests. This aspect ratio would handle all of these needs equally well, and provide a seamless visual link between the different landscapes, whilst also giving the epic, elevated feel.

As for the cameras, that was more tricky. Film appeared to be a dirty word to the some of the production team, and the door to that world was firmly shut. I had shot Every Secret Thing in NYC using Red Epic, which I liked very much. So we tested Red Epic and ARRI Alexa with as much varied Anamorphic glass as we could find from Movietech, Take Two and Panavision. I remember thinking about the beautiful imagery of the old PV Genesis camera, whose inner workings were designed by Sony. This led me to consider the F65. I’d heard reports from Andy Cooper (at Movietech) that it was an interesting camera, but I didn’t know enough about it at that time. So I added that to the tests.

We shot in a film-style test environment, with different textures, surfaces, colour temperatures, light sources and contrasting exposures, and screened it at all at Theatre 7 at Pinewood. The choice then became a no-brainer. The other cameras either didn’t have true rendition on the landscapes, or made my lens choices look very samey, so I disregarded them. The F65, however, rendered everything the way my eye saw it. The images had soul. Extraordinary. I thought, ‘maybe film has a true companion now’! It rendered the light the way that I tend to see light. The subtle colours were there. I could see the detail and aberrations that I wanted from my lens choices. And later, although I wanted to shoot Testament Of Youth on film, I ended up using this same combination of camera and Anamorphics.

Movietech had the F65 camera I wanted, whilst Panavision had the lenses. I am thankful to both companies for working together so well and supporting me. Although we tested with re-housed Kowa Anamorphics, I went with a set of Xtal express from Panavision.

I have to say that there was some negative reaction from certain quarters regarding my choice of the F65 – particularly about the back-end workflow – but that fear of change was fuel-to-the-fire for me. I had made my choice based on the quality of the images I wanted, and fought my corner. Pinewood Digital stepped up and were brilliant on the back-end side of things during production.

"Using the dimmable lights, plus the Perspex lighting box for reflections, I was able to create subtle visual shifts between each of the sessions."

- Rob Hardy BSC

The VFX are simple but stunning. How did you shoot Ava?

RH: Yes, the final result on screen is very powerful, and it was a lot easier than I imagined to shoot the VFX. I worked closely with Andrew Whitehurst from Double Negative from the early stages. He is a genius, and I considered him part of the camera crew. He was positive, a great enabler, and always able to slot around whatever we were doing. For example, although the main shoot was with the F65, I sometimes used an F55 for handheld. Andrew found ways fit the VFX to those different styles of footage, rather than me having to work other way around. I never felt restricted at all by the VFX.

Before principal photography, Andrew tested our lenses and mapped these for the VFX team. On set, Alicia wore a very tight-fitting mesh bodysuit, that just exposed what you see on screen – her face, hands and feet. We shot with our regular lighting set-up and also shot plates for reference purposes. We didn’t shoot a single frame of blue or greenscreen. DNeg did an excellent job in replacing the mesh suit with their CG AI creation, and the final results are very dramatic, in perfect sympathy with the story.

Who were your crew?

RH: I operated on the movie. The glorious Jenny Paddon was the 1stAC/focus puller working alongside Tim Morris the 2ndAC, Sam Phillips was our terrific grip, and Jay Patel our brilliant DIT, making sure the dailies from Pinewood Digital were on-time and in the format I wanted. Andrea Fishburn proved a fantastic trainee and Tom Storey took care of all things in the Go-Pro world for the CCTV footage we shot. In addition to this Stuart Howell operated Steadicam and came to Norway to shoot the second unit landscape photography. Lee Walters was my excellent gaffer. Along with Andrew from DNeg, I would also include Asa Shoul the DI grader at Molinare as part of the carema team. He helped us with the look form the very start, creating LUTs in pre-production, and did a sterling job later in the DI in integrating the VFX and live action and fulfilling my overall ambition for the final look.

How long did you have to prep, production and what were the working hours?

RH: I had six weeks in pre-production, and spent every day at Pinewood working with Alex, the production team, the actors and my camera and lighting crew. We shot the movie over the course of six weeks – four weeks at Pinewood, and two in Norway shooting the exteriors and landscapes, that doubled for Alaska. We worked 11-day fortnights, with every other Saturday off, and did 11-hour days. I think we only went over once or twice, and thankfully did not do any nights.

What was your lighting strategy?

RH: As we needed to be able to work in 360 degrees at all times, within an extensive, completely enclosed set with ceiling pieces, the plan was to light using embedded practicals. However, I did not want the stark, white light you get from strip lights and KinoFlo tubes, as that quality seemed atypical of what you might expect in a sci-fi movie. The set design was minimal – very sharp and clean, modern and clinical. I wanted to counteract that and explore ways to make it feel more warm, human and natural.

So, keeping with the idea of lighting with embedded practicals, I had the set fitted with Tungsten bulbs, around 15,000 of them in all. It took about two weeks to have them installed. Lee, my gaffer, and his team did a wonderful job. They wired and carefully labelled sets of bulbs to dimmer boards, all provided by Panalux. This gave me control of the lights in each of the rooms and corridors, and allowed me to adjust the direction, level and quality of the light as I needed. Overall, this lighting set-up let me shoot in a very naturalistic way, and gave me and the actors lots of flexibility and easier set-ups.

I knew there would be a lot of glass in the movie – windows, apertures, frames and other barriers – and wanted to find ways to treat all of this to show that Ava is effectively trapped, a slave. I asked Lee to build a long, thin strip of tungsten lights, contained in a Perspex box. I used it beside the camera to create reflections with geometric shapes as I composed the imagery, and get over that sense of her isolation.

The movie is punctuated with Ava Sessions, as Caleb and Ava interact during the Turing Tests. In each session they play a game, and the dynamic between them changes, gradually becoming more tense and intriguing. Using the dimmable lights, plus the Perspex lighting box for reflections, I was able to create subtle visual shifts between each of the sessions – gradually moving from bright to dark as things turn more sinister and mysterious.

What was the reasoning behind your camera movement?

RH: In the underground lab settings, the camera is generally and observer. But, as it’s a thriller, I gave a constant sensation of us just leaning in, to get a closer look, by using “imperceptibles” – slight, slow forward motions of the camera, to give a creeping sense of dread. During the Ava Sessions I purposefully positioned and moved the camera to make the audience question who’s trapped and vulnerable? Is it Caleb or Ava?

The exteriors of the glaciers and forests counterpoint Ava’s enclosed world, but I didn’t want typical swooping aerial imagery. The landscapes had to be much more than just throwaway shots. They had to have intention and intensity. To achieve the strange sensation I wanted, my instruction Stuart Howell was to take just one lens – either a 32mm, 25mm, 18mm – and to hovver just above the ground, with one central element in frame – like a mountain, log, chunk of ice, waterfall – and shoot controlled linear moves, a jib up, track along or a track back. I love the images we rendered from the gyro-stabilised F65. We got a kind of Ansel Adams-type result.

How did you work with Alex during production?

RH: I attended scripts sessions each morning with Alex and the actors, and discussed the best ways of getting to the emotional heart of each scene. There were very long dialogue scenes, like a theatrical play, and we worked on finding the points in each scene when the emotions heighten or the plots twists, and how best to capture these.

Alex is a true collaborator, and he engendered a great family spirit throughout the production. Even the sparks had read the script and were excited by the plot. As a writer with some formidable credits, he understands filmmakers and knows ultimately what makes for a good cinematic experience. There’s no pretence with Alex, just truth. He was always up with me, beside the camera, working with the actors, always willing to show trust and he had no problem in making changes.

What can you tell us about Testament Of Youth?

RH: It’s the same actress, Alicia, same camera, F65, plus and F55, and same Anamorphic lenses, as on Ex Machina, but the similarities stop there. Testament Of Youth is a sad, harrowing, visceral journey through an appalling period of history with heightened emotions.

We viewed split screen tests, with Asa at Molinare, of digital cameras versus 3-perf 35mm and 16mm, which looked gorgeous. But you need will and determination to fight for film these days, and I was the only one pushing for it. I knew the F65 from my work on Ex Machina, and shot with that alongside the F55 – probably about 50-50.

Although we were on a northern road trip between Leeds, York and Scarborough, the movie is very much about the landscape of the face, and seeing the world through the eyes of the protagonists. I knew Alicia’s face very well. My goal was not to create a typical period-drama look-and-feel, but rather to be true to the light around us. I kept the look soft and natural, absorbing the textures and wanted to create a feeling of the air around us.

My constant journey is to control light, and not rely on post production. I wanted to use the camera to do that, and to keep it as authentic as possible to the time we were there.