The Storyteller

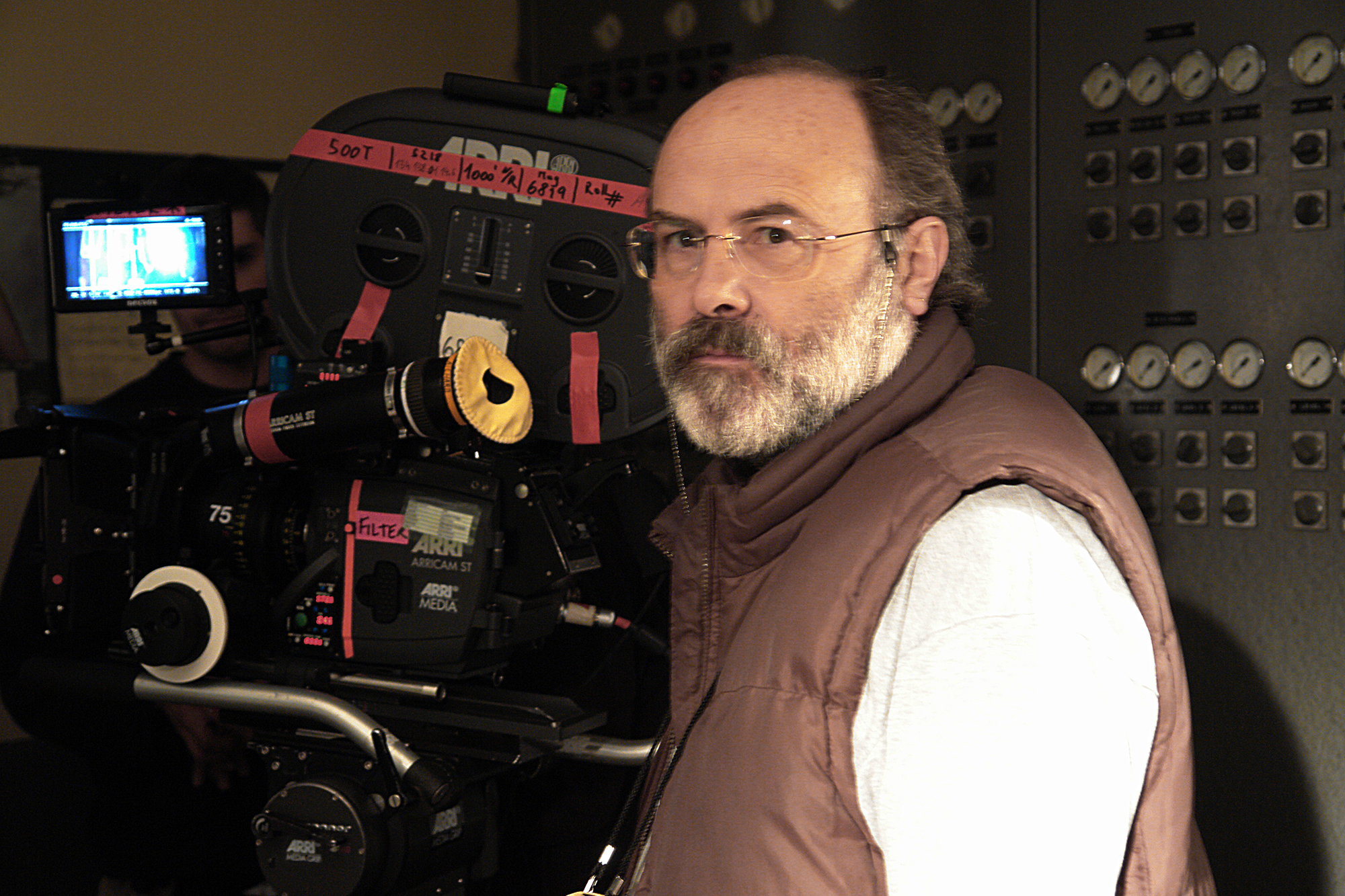

Clapperboard / Richard Greatrex BSC

The Storyteller

Clapperboard / Richard Greatrex BSC

BY: David A. Ellis

Award-winning cinematographer Richard Greatrex BSC, now an honoury member of the BSC and these days a dedicated stills photographer, was responsible for the look of dozens of films, including Mrs Brown (1997), Flawless (2007), A Knight's Tale (2001), Warriors (1999), The Woman In White (1997), for which he earned a BAFTA, and the highly-acclaimed Shakespeare In Love (1998), for which he was Oscar-nominated.

Although he no longer shoots movies, having moved into the world of photography, he still likes to tell stories with his cameras. Brandishing his Canon or Panasonic Lumix DSLRs, he photographs local people, artisans making beautiful or functional objects - such as bicycles and guitars - and also does community work with disadvantaged children.

"Thirty years as a cinematographer taught me a great deal about storytelling," he says. "I use the tools and methods of filmmaking in my photography. Composition, structure and rhythm. Establishing shots, close-ups, points-of-view and eyelines. Montage, dissolves and superimposition. Together they make stories. We all need stories."

Richard Greatrex was born in Swansea, South Wales, in 1947. After leaving school he trained to be an electrician, staying in that role for eight years. In 1968 he worked as a technician at the University Of Sussex. Following this he became a mature student at Coleg Harlech (Wales). He then entered Balliol College, Oxford and studied politics, philosophy and economics, which he says gave him a questioning mind.

It was whilst at university that his interest in film began, previously having had no interest in the business. A fellow student, who became a friend had a Sony Porta Pak video camera which he couldn't operate. Greatrex, who was technically-minded did some shooting for him, covering the mining community in South Wales. Later, Greatrex went to America for a couple of years working in Tennessee on community videos and worked on material for the United Mine Workers of America. On his return to South Wales he made a series of videos documenting what life was like without the pit.

Having grown tired of the video equipment he was using, he decided he wanted to learn about film cameras. He went to the National Film & Television School to study cinematography, and says it was the best three years ever, because he was introduced to a whole new world he knew nothing about. This included being introduced to Michael Samuelson, who would take students around film sets to investigate the lighting being used. Several years later, it was Samuelson who suggested that Greatrex join the BSC.

Before leaving film school as a qualified DP, Greatrex shot concerts. After leaving, his film career took off. His early projects included shooting the heavy metal band Judas Priest and the opening night of Channel 4. His first feature for the cinema was Knights And Emeralds (1986, dir. Ian Emes).

Recalling the challenges of being a cinematographer, he says Warriors (1999, dir. Peter Kosminsky), about the PTSD affecting a Bosnian peace-keeping force after their return to civillian life in the UK, has became one of his favourites.

"The director's style, was to try to recreate things as they really happened," he says. "For example, you couldn't be the other side of a door, you had to go through the door with them, which meant changing the exposure correctly as you walked through. There were lots of physical challenges like this. In a battlefield scene none of us were really sure where the safe explosions were, neither did the actors or the extras.

"Shakespeare In Love was tough too, because it was a huge set-up, which I hadn't experienced before. It cost a lot of money and there was a lot of expectation riding on it. Also, it was a long shoot and the studio were watching all the time. People from the company would want to watch dailies with you. So I got into the habit of going to the lab at five in the morning to see the dailies before anyone else."

Sir Sydney Samuelson CBE said, "The movie Shakespeare In Love was beautifully photographed. One of my great puzzlements was how come it did not go on to win the actual Oscar. Richard was not only a superb technician, he was really a nice guy, a pleasure to be with and a loyal rental customer of ours."

"Thirty years as a cinematographer taught me a great deal about storytelling. I use the tools and methods of filmmaking in my photography. Composition, structure and rhythm. Establishing shots, close-ups, points-of-view and eyelines. Montage, dissolves and superimposition.

Together they make stories. We all need stories."

- Richard Greatrex BSC

Greatrex says he never worked on second units, but was always conscious of wanting a consistent look to each production and asked his main camera team to shoot second unit footage. "I think bringing in a second unit completely cold, and without any of our members, was a tough one. When we needed a second unit, I ensured the B-camera operator went along with a crew they chose."

Greatrex, who shot all of his films on celluloid, admits to not being overly technically-minded. "I am not really interested in things like that. I would always keep the technical stuff as standard and consistent as I could, so I knew what I was going to get. I stuck with the same filmstock for years and I would stick to the same camera." He says he started out with Panavision and later went on to ARRI cameras. "The camera was important to me in only two respects. Did it have a good viewfinder, and would it take a set of lenses I always liked, which were Canon."

Asked what he thinks of digital imagemaking, he says, "It's a completely different world to film, but the cameras are only there to record the story that you are going to put in front of the audience. So saying one is better than the other is nonsense. I think people who say they prefer the look of film are being nostalgic. Digital as well as film is a recording media and it is up to you to make the story in front of it. With digital you can make it look like anything as long as it's been exposed properly."

Are there any cinematographers he admires? "As far as DPs go I admire the work of those where you cannot tell who shot it. I don't have a great deal of admiration for DPs who bring a style to the film regardless of the needs of the film. One DP who shines to me is Roger Deakins CBE BSC ASC. He reads the script, he understands the director, he knows the story, he knows what is needed and can change his style."

His advice to newcomers wanting to become cinematographers is simply go out and make films. "There is nothing to stop you today, because so many of the costs have been reduced. Digital equipment is much cheaper and simpler to use, and you don't need the big crews. The less kit I could see on my set the happier I was, and if you could do it with one light source you were getting there."

Asked why he retired from cinematography - his last outing as a DP was the TV mini-series Moby Dick (2010) - he says, "I quit when things were really good. I didn't want to go through any professional decline. I had seen fellow DPs start to take on rubbish projects, because they felt they had to as the offers weren't coming like they used to.

"The other reason was, if you have developed a good working relationship with a director and were lucky enough to continue that relationship, which I had with three or four, you could have a say in the way the story was told, the way it was developed and the way the shots were put together. You could become a creative member of the team. The one thing you never had influence on was the story itself. I reached a point that I wanted to tell my own stories in my own way."

Greatrex now lives in the small, historic town of Hay-on-Wye, Powys in Wales, from where his plies his trade as a photographic storyteller. His visual works include portraits of industry friends and colleagues such as Nina Kellgren BSC, Steadicam operater Gerry Vasbenter and Russell Allen at ARRI, travelogue images from places such as Japan and Cuba, illustrative pictures for books, and shots of local artisan makers. Many of these are published on his website.

"Stories help us make sense of our world, whether thay are brief or extended, simple or complex." He says. "I see myself as a storyteller."