Deja View

Paul Cameron ASC / Total Recall

Deja View

Paul Cameron ASC / Total Recall

In 1990, Phillip K. Dick’s classic short story We Can Remember It for You Wholesale was loosely adapted into the film Total Recall by director Paul Verhoeven. The resultant cocktail of violent shocks, startling visions of an interplanetary future and earnest identity politics has since become iconic.

The story followed Doug Quaid, an everyman of the future seeking artificial memory implants of a mission to Mars. It swiftly becomes unclear whether his memories of secret agent work are real or not.

In May 2011, production began on a Columbia/Original Film remake combining elements from the 1990 film and the short story. The new film would retain many of Dick’s original plot details, set on a dystopian Earth rather than Mars, as well as political resonances: Earth has degenerated into two battling superpowers, New Shanghai and Euroamerica.

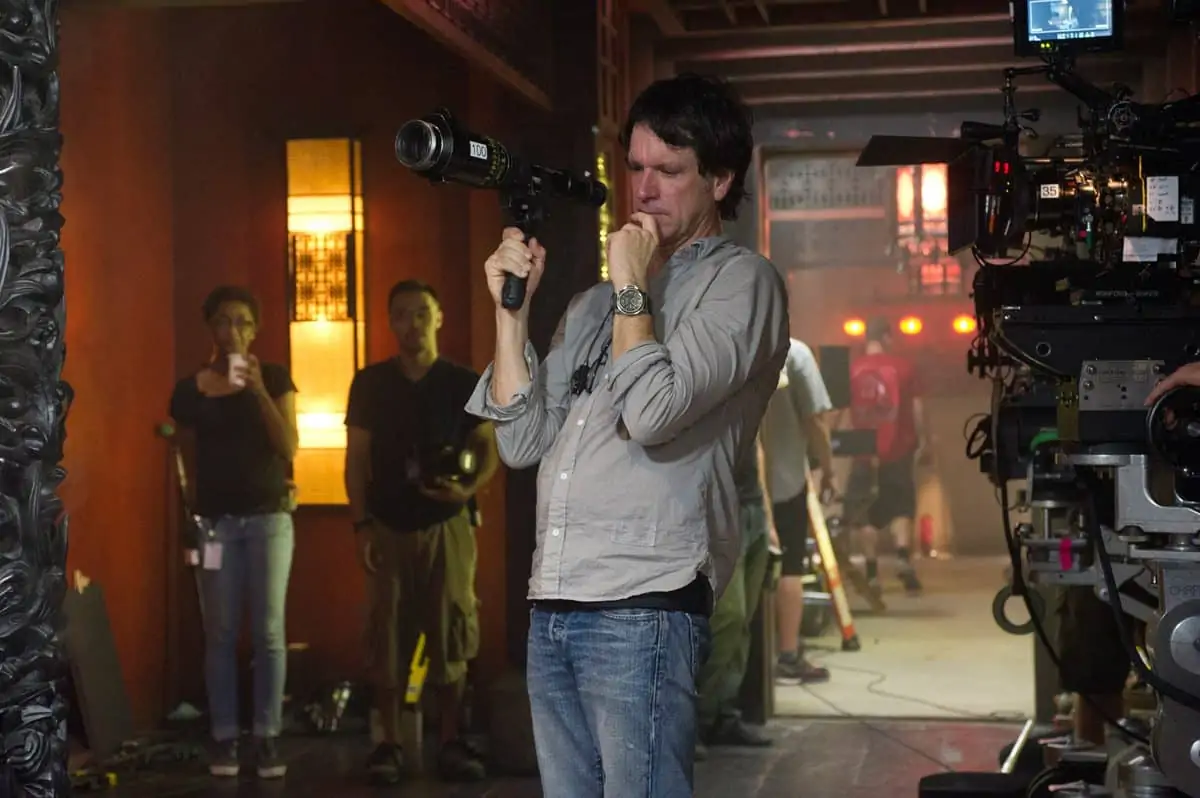

Director Len Wiseman called Paul Cameron ASC, who had just wrapped on Man On A Ledge, asking the DP to work with him in crafting a new vision of the 2084 dystopia. Their first film together turned out to be a creatively satisfying experience, shooting over 83 days in and around Pinewood Studios in Toronto, Canada.

Colin Farrell plays Quaid alongside female leads Kate Beckinsale and Jessica Biel, with turns from Bryan Cranston and Bill Nighy. Neal H. Moritz and Toby Jaffe produced the film from a script by Kurt Wimmer, Mark Bomback and James Vanderbilt.

“Fortunately, Len wanted a very rich, dark and opulent film,” says Cameron. “He asked me to bring a rawness to the imagery, something to help blend the hyper-real visual effects; he also asked for it to have its own gloss. We knew a high bar had been set by Verhoeven and Jost Vacano, who lensed Total Recall, so we made a new film in its own right rather than updating the original iconic characters and imagery.”

Having worked with Tony Scott (Man On Fire, Déjà Vu), Dominic Sena (Swordfish, Gone In Sixty Seconds) and Michael Mann (Collateral), Cameron is no stranger to large budget action films, although he has also worked on smaller, sensitive human dramas featuring intimate portraiture. Even so, the budget of his latest was a revelation and came with an array of surprising and gratifying possibilities.

Estimated at around $200 million, Cameron says, “It’s almost unfathomable to me, but that’s the incredible thing about budgets – no matter what the scale of the project you always have a larger appetite! Fortunately exec producer Ric Kidney is very supportive and understood the challenges we faced.”

The camera, lighting and art departments employed a small army of people. Walking the stages of Pinewood during prep, each open door revealed hundreds of set constructors and dressers, rigging for stunts, lighting and grip.

Working with Cameron were Angelo Colavecchia and Mike Cirella, A and B operators. Key grip Robert Johnson, a Toronto local, rose to the challenge of meeting all grip needs along with rigger Jon Billings. Pat Reddish came in from Park City to gaffer the movie with rigging gaffer Patrick Lennon.

“This is my second film with Pat,” says Cameron. “Patrick is truly gifted and a consummate gentleman; he provided amazing support.

“I was very fortunate to have a top level camera crew – all from Toronto. I am extremely demanding on my camera crew on any film, but this one in particular required a lot. Russel Bowie, my A cam first assistant is amazing, as well as B first Ciaran Copelin.”

"My theory is, although you need to know the film inside out and be as specific as possible about every detail, you also need to be open to spontaneity and making changes."

- Paul Cameron ASC

The scale of the film demanded three months of prep, with extensive pre-vis, storyboarding, scouting and re-scouting to have as much planning as possible achieved beforehand.

“My theory is, although you need to know the film inside out and be as specific as possible about every detail, you also need to be open to spontaneity and making changes,” remarks Cameron. “The downside of prep is you get attached to what you’ve thought about over and over again. Of course, many of the sequences need to be executed precisely for VFX, but there is always room for discovery. Fortunately Len is a fearless director, so when you pitch a good idea on set and it changes the preconceptions, he will just turn and say, ‘Cool, let's do that. It’s better that way!’”

Cameron and crew were prepped and ready to shoot Total Recall on Panavision 2:40 Anamorphic with Fuji stocks, but eight days before principal photography began they switched to Red Epics. Cameron kept the Panavision C and E series lenses, and a special set of flare lenses (C series installed with small ventricular mirrors, designed for Cameron by Dan Sasaki at Panavision), and shot 2:40.

Although a challenge to get the package ready on time, Cameron is well-versed in thinking on his feet and adapting quickly to changes. “Total Recall is the first large-scale film to utilise the Epic in 2D,” he said. “Panavision had to manufacture many new pieces of support equipment. We had to ship in, create and test the digital workflow with Light Iron.

“Russel Bowie did a tremendous job turning around the entire package to Epic,” he says. “We maintained a rule of thumb with Red and Panavision: we were not going to update any firmware on set. Bodies would be updated and tested for stability before they arrived. In a funny way the Epic bodies themselves were like the new disposable camera, we just traded them off constantly.”

As Wiseman wanted as naturalistic a look as possible, Cameron utilised multiple unique, large-scale locations around Toronto and maintained an ethos of integrating natural light. His crew was tasked with erecting massive greenscreens, rigged quickly and often in very unorthodox ways; they covered every nook and cranny of large outdoor spaces and worked around structures such as the postmodern concrete facades of the University of Toronto and the glass dome at Roy Thomson Hall.

A hovercar chase sequence presented one of the greatest challenges, shooting on an airfield north of Toronto and major motorways, using actual hovercars on high-speed racing chassis. “And the cars weren’t air conditioned – the poor drivers were cooking!” recalls Cameron. “Fortunately we were happy with the results in the end. It looks great, with that water canal down the middle.”

They also worked hard to present a 360-degree immersive viewing experience. Some sequences had three to eight dolly moves to achieve non-stop circular motion around the action and others employed the use of 32 Canon 5Ds to track a circle all the way around the back of a 3D hologram.

Cameron typically works with three to four cameras for most scenes. The compromise, of course, is at times the eyelines aren’t quite as tight, however using more cameras means capturing quickly and authentically the many ways in which Cameron and Wiseman can see each scene unfolding.

“At times the focal lengths are longer in order to stack more cameras together,” he says. “The bottom line is the quicker you start shooting and the more chances you take, the more real the footage is. It’s something I learned while working with Tony Scott over the years. It usually requires a slightly longer setup to get all the cameras in and ready, coordinating the operators to be at various places at specific times, and a lot of reframing and resizing within a scene. It’s a bit like conducting a visual orchestra. Mind you, watching it unfold on the stack of monitors while shooting is quite satisfying when it all comes together!”