Eyes wide open

Clapperboard / Nina Kellgren BSC

Eyes wide open

Clapperboard / Nina Kellgren BSC

BY: Valentina Valentini

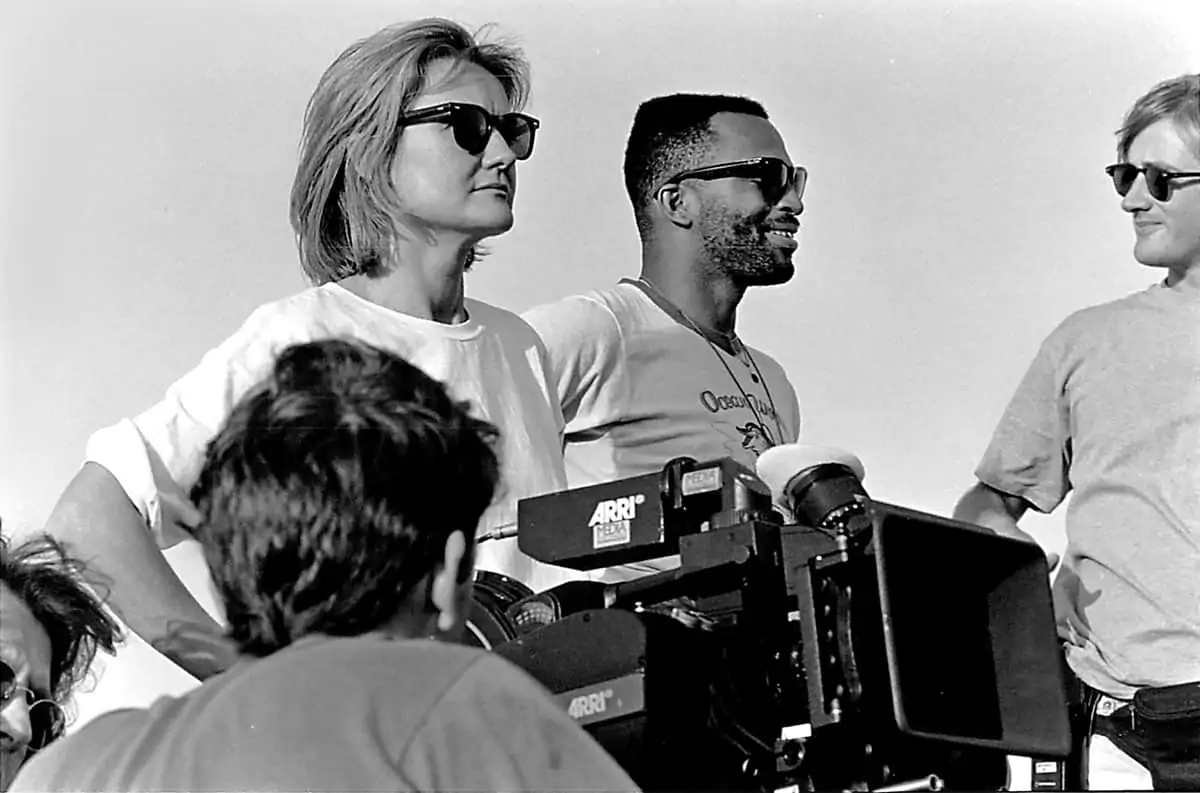

Lead image: Up on the crane during the shoot of Solomon & Gaenor

Nina Kellgren BSC was recently named most prolific female cinematographer by the British Film Institute. Though this was not the path she thought she’d lain out for herself, her 30-year career has brought her not only BAFTAs, but respect, admiration and collaborations that, at the end of her career, leaves her on the up not only in status.

“I have had a marvellous working life,” she says over tea in North London. “I feel very fortunate and privileged to have found cinematography – a perfect combination of art, interpreting the world visually, working with skilled and talented directors and teams, and a decent income.”

That said, of course it was not without its hardships and frustrations. Kellgren, who grew up in the UK in the middle of the last century is now focusing her energy on advocating for inclusion and diversity in the film industry, connecting cinematographers internationally through IMAGO, the international federation of cinematographic societies, teaching the next generation of filmmakers and creating her art when the inspiration strikes.

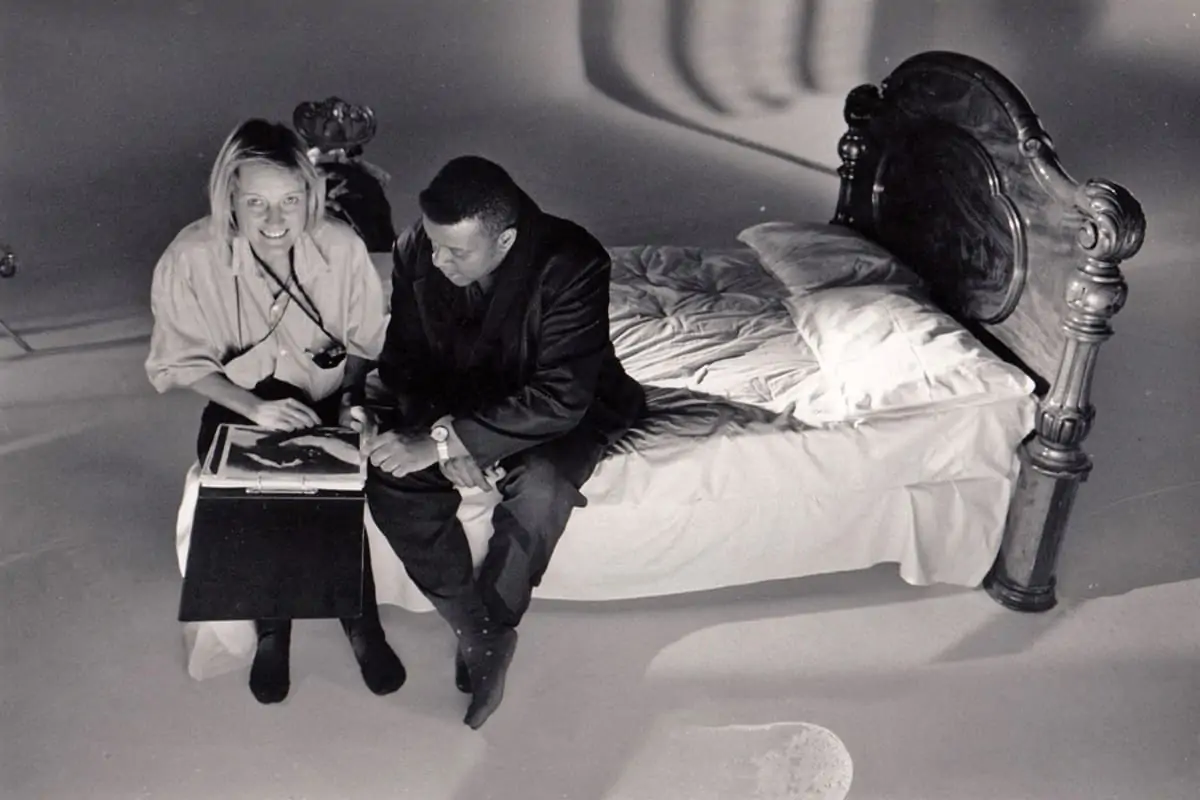

Her credits include countless documentaries, such as Drowning By Bullets, which won the FIPA d’Or at Cannes and an Amnesty International award, Looking For Langston, Al Pacino’s Looking For Richard, BBC’s The Women Who Smile and Under The Sun series, Young Soul Rebels, which won the 1991 Critics Prize at Cannes, Solomon & Gaenor, which won a BAFTA Award and was Oscar-nominated for Best Foreign Language film, The Making Of Maps, which won her another BAFTA, along with many other narrative and documentary projects and commercials with Paul Arden (Saatchi & Saatchi) at Arden Sutherland-Dodd and Thomas Thomas Films.

She won the Panavision Craft Award for Cinematography in 1999 and, in the same year, was elected to the British Society Of Cinematographers as the third woman ever. Kellgren was on the Board of Governors from 2005-2008. Since 2000, she has been a visiting tutor at the UK National Film & Television School, has served as a member of various BAFTA jury panels, and was on the international commissioning and mentoring panel of STEPS South Africa in 2001. From 2005 to 2006, she was on the Board of Directors of Women In Film & Television, UK, and in the last couple of years began her most recent outreach work as a member of the board and VP of IMAGO.

Kellgren was born of an American nurse and a Swedish-Russian doctor working with the American and British armies, respectively, who met during World War II. “It’s a Diaspora tale,” she says, linking the beginnings of her own narrative to her current work with bringing together cinematographers internationally. “I grew up in a very open and multicultural household.”

And so she graduated with a Masters in Fine Art from The Slade School Of Fine Art in 1972 and was doing still photography among her paintings, had a studio and began to get some exhibitions and teach a little as well. Of course, she used to venture out of her solitary artist life to catch a movie at the local cinema.

“I remember watching Kurosawa – I know, I know, why not start at the top, right? – and I remember thinking ‘I don’t know how to do that, but I know I can.’ Firstly, though, I didn’t know being a cinematographer was a job. And secondly, I didn’t know women could do it. But nonetheless, I thought, ‘that’s it for me, that’s what I want to do.’ I just needed to find out how to do it.”

Because Kellgren didn’t have any connections to the film industry – though her personal life was now filled with the work of Vittorio Storaro, Robbie Muller, Raoul Coutard and Gordon Willis – it took her a while to find it. She knocked on anyone’s door she could think of to try and begin to train herself as a camera assistant, walking into rental houses and asking to be taught anything and everything.

“When you find something you want to do, you pursue every path,” she remarks. Finally, she landed in an assistant position in the world of television documentaries.

Channel 4 began airing in November of 1982, and around that time there were quite a number of documentaries being made about women’s issues – such as pregnancy, cancer and working rights. There was a cinematographer, Diane Tammes, who may have been the first woman in the UK to get her union ticket, which at the time, was essential for working. Simply because these “women’s stories” needed female camera teams to be granted access into labour wards and other sensitive areas and subjects, that was how a number of women got union tickets and started working, as Kellgren explains it.

“I had been finding my feet,” she says, “but Diane gave me my first job in television as a film camera assistant. It was the beginning of a swiftly moving path towards becoming a cinematographer shooting fiction; and it was a timely breakthrough, as I also had a child to support.”

"What’s really hard for all of us in the film industry to be aware of – and I include myself in this – is that exclusion is an active process.

So many times you have heard: ‘Well, it’s just like that. There aren’t any women. It’s too hard. They don’t want to be cinematographers…’ None of which has ever been the case."

- Nina Kellgren BSC

Channel 4 also had an experimental arm to it in the mid-80s, which set up workshops that were funded and gave emerging filmmakers license to make films to air on mainstream TV. Kellgren began what would be a working relationship that has lasted until today with director Isaac Julien. Sankofa was a black film collective and Kellgren shot the critically acclaimed Looking For Langston, which Time Out Magazine called, “visually stunning and atmospheric black and white… moody, moving and memorable.” It was a poetic documentary that weaved-in recreated narrative to tell the story of Langston Hughes and the Harlem Renaissance, which premiered at Berlin Film Festival.

“Berlin has quite a proactive audience who have always been vocal,” recalls Kellgren. “They asked us why a woman shot this film. Isaac responded with ‘Why not?’ But we were able to have an interesting discussion on the stage about that question: he’s gay and black and I’m white and heterosexual – you never know where those great collaborations are going to come from. It’s not someone who looks like you, it’s all about sensibilities and empathy to get the best stories out there.”

As to the point that the industry is still having conversations around inclusion and exclusion, Kellgren says it means that unconscious bias is alive and well. “I was on an equality committee back then in the early ‘80s, and I am now,” she says.

When she joined the board of IMAGO, she proposed an additional committee on diversity and inclusion, which the board took up unanimously. President of Estonian Society Of Cinematographers Elen Lotman ESC and Kellgren are co-chairs and have run the Friday events on diversity at the Camerimage Festival Of Cinematography for the last two years with great success and participation by Illuminatrix and sponsorship from ARRI, Panavision, Hawk, Panalux and Vantage.

There are only five women in the BSC today, and Kellgren can’t count how many times she’s been asked why this is so. Things are changing at a rate far slower than is needed or warranted.

“What’s really hard for all of us in the film industry to be aware of – and I include myself in this – is that exclusion is an active process. So many times you have heard: ‘Well, it’s just like that. There aren’t any women. It’s too hard. They don’t want to be cinematographers…’ None of which has ever been the case. You have only to look at the range of impressive work on the Illuminatrix website, International Collective of Female Cinematographers and Cinematographers XX in the US, to see this is not true.”

Kellgren is confident that things are shifting more rapidly now, though. There has been a groundswell of studies, awareness campaigns and desire for change in the film industry recently, which she feels is heartening. “BSC President Mike Eley has said that the BSC is committed to the aim of encouraging women cinematographers in our industry,” she adds.

Kellgren is at the end of her career, so she says, though she’s currently prepping for another project with longtime collaborator Julien about the American social reformer and abolitionist, Frederick Douglass.

“I first went to IMAGO as a delegate three years ago,” says Kellgren. “It’s a great organisation and more important than ever, enabling cinematographers to share information and collaborate on international common interests. As countries retreat into nationalism, keeping borders open is crucial through whatever your discipline is. In these times of Trump and Brexit, we must remain open to understand each other. Telling stories is how we make sense of the world and we all benefit from having a film industry that reflects the diverse reality of the world we live in.”