A Moment Of Critical Mass

Across The Pond / Mark London Williams

A Moment Of Critical Mass

Across The Pond / Mark London Williams

Sir Patrick Stewart recently ended his hosting of the Academy’s SciTech awards with an off-the-cuff rendition of Puck’s closing monologue from Midsummer Night’s Dream : “If we shadows have offended/Think but this, and all is mended /That you have but slumber'd here /While these visions did appear”.

The “visions,” of course, were what was being honored at the SciTech dinner - which most viewers know as a highlight reel during the main Oscar telecast. Yet they would still miss some of the highlights.

Among this year’s honorees were Leonard Chapman and his team for the company’s “Hydrascope” - Leonard for the design, Stanislav Gorbatov for the electrics, and David Gasparian and Souhail Issa for the mechanics and integration. The invention allows a shot “as old as movies themselves,” as Stewart put it - the crane shot - to be done in and out of, and through, fresh or salt water.

2nd Row: Vikas Sathaye, Shane Buckham, Tom Hahn, Jason Smith, Alex Wells, Jason Reisig, Cristin Barghiel, Abigail Brady, Jeff White

3rd Row: John Coyle, Rob Jensen, Mike Jutan, Rachel Rose, David Gasparian, Martin Watt, Alex Powell, Brad Hurndell, Jerry Huxtable, Mark Tucker

4th Row: Adam Woodbury, George ElKoura, Dirk Van Gelder, Souhail Issa, Stanislav Gorbatov, Leonard Chapman, Joe Mancewicz, Matt Derksen, Jonathan Egstad, Jeff Lait, John Lynch, Jon Wadelton. ©A.M.P.A.S.

On the digital side of the equation, awards were also given to a lot of software and digital innovators as well, or in some cases “re-honors,” for previously awarded systems still being updated, such as foundational VFX systems like Houdini animation and Nuke compositing. Nuke’s honor included two from the U.K., Abigail Brady and Jon Wadelton. Brady made a bit of history herself, as the first transgender honoree in SciTech’s history, but as a result, now finds herself among a too-small handful of women who receive such honors. ILM’s Rachel Marie Rose was one for her role in creating ILM’s BlockParty rigging system, who noted her award was “proof you can,” to any other young women wondering about scaling the gender battlements of a tech career.

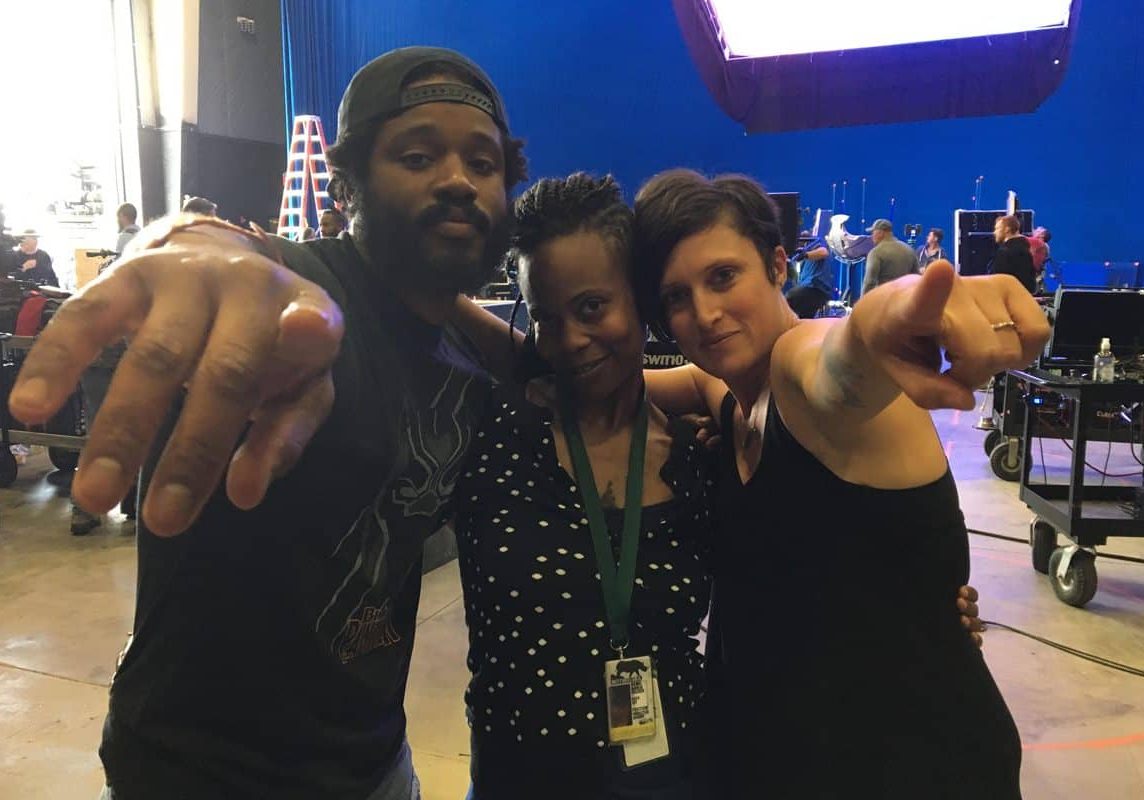

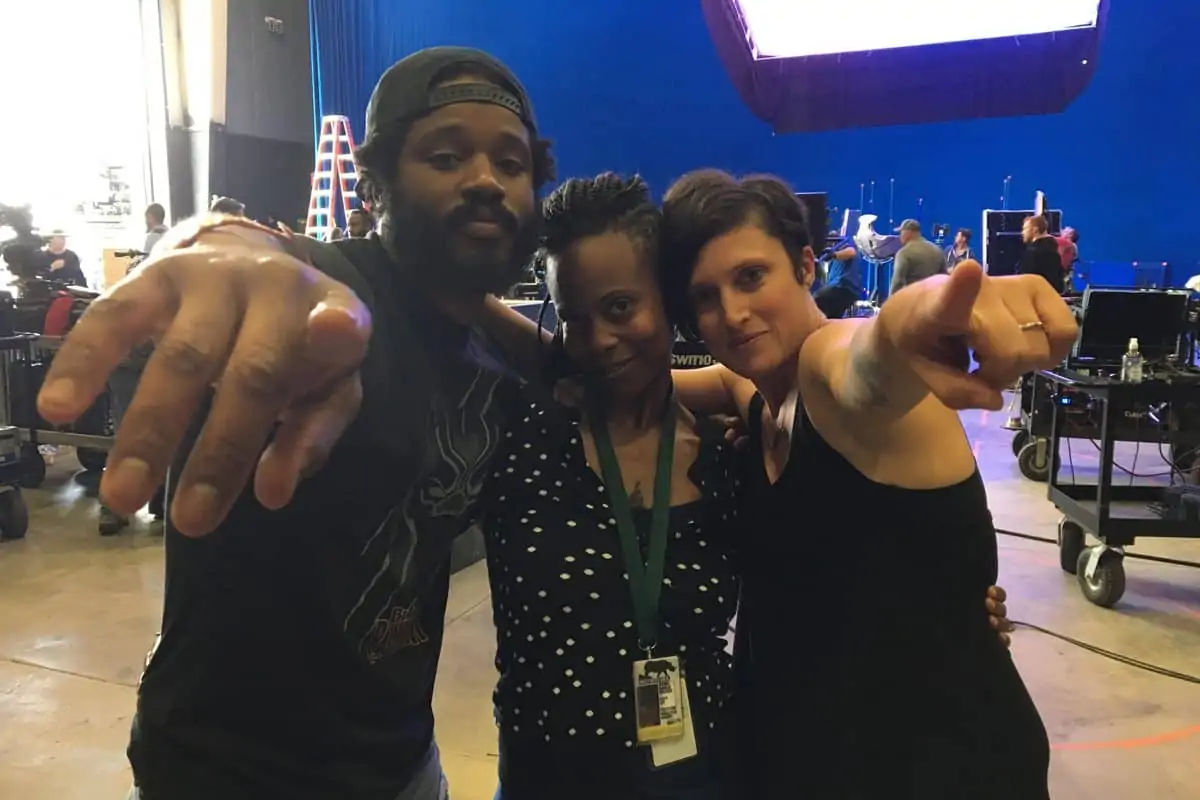

And yet some of those battlements are giving way, just a tad. We recently caught up with Hannah Beachler, whose resplendent production design on Black Panther is a key part of the accolades the film is winning. She’s been a collaborator with cinematographer Rachel Morrison since they both came up with director Ryan Coogler on his lauded indie effort, Fruitvale Station.

Of the battlement-breaking Morrison - who is, of course, the first woman to shoot a feature and get nominated for an ASC Award or Oscar for it - Beachler says, of the two years spent on Panther, she was “really excited to take a journey like that with people you know and love and aesthetically respect. Ryan is the type of director who develops his crew, and brings them into his fold as family.”

Photo Credit: Location Mgr. Ilt Jones

Photo Credit: Location Mgr. Ilt Jones

Of her role in that family viz, Morrison teases that “sometimes I’m the doting mother or the bratty sister,” but in the end, “you’re still loving family.” Or in the case of Beachler and Morrison, neighbors in Louisiana.

Of her neighbor’s eye behind the camera, Beachler says “Rachel in particular is good about sitting down and talking about the aesthetic - a sense of how the lighting design will be as how it pertains to the set - how we can play with it in the sense of using aesthetic through our sets to capture lighting. It’ll be very noticeable how the two play together - that was a lot of collaboration between Rachel and me (on this film).”

And Beachler wasn’t the only production designer to shout out to her DP; at the Art Directors Guild awards, Dennis Gassner capped off the evening with a win for his design for Blade Runner 2049, and gave loud thanks to Roger Deakins (and others) for the “amazing collaboration.”

Deakins’ name is, of course, being bandied about quite a bit on the awards trail, as the likely favorite for both ASC and Oscar, though the latter is often prone to “sweep balloting” if a certain film catches fire with the other branches of the Academy.

"We are in a moment of critical mass. The more types of women in positions of power will continue to lead to more types of women being brought to the table. The current movement is different because folks are finally seeing that female-helmed projects make money."

- DP Autumn Eakin

We’ll know by our next column, of course, how it all pans out. Among those nominated with Mr. Deakins is Bruno Delbonnel, for Darkest Hour, who immediately turned around and praised his production designer, Sarah Greenwood, when we spoke with him. He cited her “fantastic job in recreating what London was. Everything came from the production design,” including, he allows, his own sense of what wartime London was like.

He took into consideration the dimming of lights during blitzes, and the fact that “a lot of things were blacked out, (like) Buckingham Palace.”

But his sense of lighting also derived from character, as he considered Churchill “a very special man who wanted power, but didn’t want it. There’s a duality,” as he’s said before about his film’s lead character. And he used that duality - wanting to be in the light, yet sometimes in shadow - to help create his lighting scheme.

“In the beginning of the movie there’s this big crane shot (in Parliament) - then we track back and see the bull hat. The bull hat is in shadow. I wanted the beginning to be like Churchill, hiding. When we go into his bedroom, he’s in pitch black. Then he lights his cigar. It was always playing with the idea ‘he cannot hide anymore.’”

To capture this tale of Sir Winston coming out of hiding, and straight into the history books, Delbonnel used an Arri ALEXA, though he hastens to add, a studio version - “the only one with with an optical finder, which I really like.”

To this he added lenses from Cooke, Fujinon, and Angénieux. He liked the latter because “we wanted a lightweight zoom - because of all the fake steadicam shots we were doing.”

By which he means prowling the recreated war cabinet rooms and bunkers with a camera mounted on a Stabileye lightweight remote head. “It’s an English piece of equipment,” he notes, of which Churchill would doubtlessly approve. “A lightweight remote head that a grip can handle, and In some ways more interesting than the Steadicam. It allows you to move faster, and we were able to (do that) without flying out the wall. When you fly a wall you waste half an hour or more.”

He also mentioned that going handheld wasn’t an option, because he thought that would make the film look too much like a documentary, even if it was recreating so much shared history.

But whether doc or narrative, portability and ease of movement is increasingly important for digital-era DPs. That was confirmed by Autumn Eakin, who was part of a “DP First: Women Who Shoot” panel at last month’s Sundance Film Festival.

The panel was part of a series of programming sponsored by Canon, who is the camera sponsor of the event.

Eakin, who has operated on series like Master of None and American Pickers, has also DP’d HBO projects like Lenny, and numerous other documentaries, such as 11/8/16, and the upcoming Hard Hatted Woman.

She’d already switched to digital gear “in narrative before my non-fiction work, with the good ol' Panasonic HVX200! Haha!,” but finds that lighting trends that began in earnest on the docu side, like LED and lightweight illumination sources, “are making their way into narrative. Even the burliest electrics don't want to lug a bunch of sixty pound lights around if they don't have to. I'm looking forward to seeing what adjustable diffusion will become. I saw Chimera's Active Diffusion from NAB and while it's in its infancy stages it could mean not having your crew taking the time to cut and line frames.”

She says that DPs “feel the pressure to do set ups as quickly as possible in all fields. As someone who shoots narrative, doc and commercial projects the unifying aspect is always how to satisfy my eye, the director and the schedule. The idea that documentary filmmaking is always in need of quick set ups and minimal lighting is a misconception. It just depends upon the style of the project. On Lenny, an HBO doc-based anthology series which just premiered at Sundance, we had proper prep, camera tests and time to rig lights in the space prior to filming. Whereas on The Light of the Moon, a narrative film I shot that won the SXSW Audience Award, we had such a tight schedule that I had to weigh out whether we had time to have the Swing take the flights of stairs down to the truck for the meat axe or if I could just 'flag' the wall off in post.”

A similar consideration, even if at a different scale, to what Delbonnel, and director Joe Wright, wrestled with for Darkest Hour’s narrow bunkers and flying walls.

As for Delbonnel’s co-nominees, in particular Morrison, does Eakin think the landscape for female cinematographers is getting wider? More inclusive? She allows that it is, but “maybe that's a delusion we have to tell ourselves, because if you look at the numbers they've barely moved in decades. But I think we are in a moment of critical mass. The more types of women in positions of power will continue to lead to more types of women being brought to the table. I believe the current movement is different because folks are finally seeing that female-helmed projects make money. And as filmmaking is an art and a business, money talks and the public is saying they want more women involved in making films by using their wallets.”

As for the non-public, which votes on awards, we’ll be back in our next column for the wrap-up of this year’s statue season, after the ASC, BAFTAs, and Oscars make everything official for the record books.

But you don’t have to wait for either wallets or envelopes to open to write us anytime: AcrossthePondBC@gmail.com.

See you next month.