Eye Spy

John Mathieson BSC / The Man from U.N.C.L.E

Eye Spy

John Mathieson BSC / The Man from U.N.C.L.E

BY: Adrian Pennington

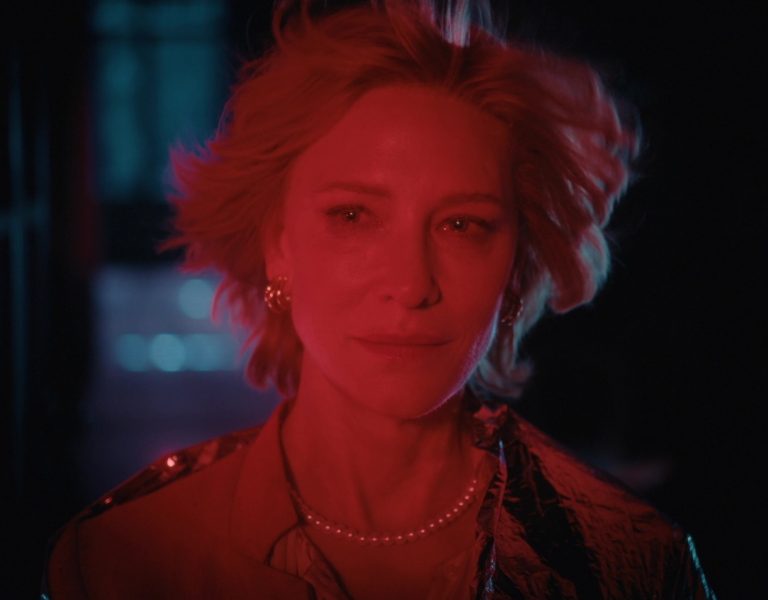

Guy Ritchie's new spy-fi action comedy pairs a duo of special agents on opposite sides of the Cold War, in roles popularised in the 1960’s MGM TV series starring Robert Vaughn and David McCallum. The characters, like the cars featured in the movie, are vintage, but the story is new, writes Adrian Pennington.

For the film, Ritchie and co-writer and producer, Lionel Wigram, conceived the idea of an ‘origins’ story that would reveal how CIA operative Napoleon Solo (Henry Cavill) and KGB agent Illya Kuryakin (Armie Hammer) met and arrived at their unlikely collaboration for the mysterious United Network Command for Law and Enforcement (U.N.C.L.E.).

Philippe Rousselot AFC ASC, who had lensed Sherlock Holmes: A Game Of Shadows for Ritchie was assigned to the project but unfortunately had to withdraw at the eleventh hour. So the ball passed to John Mathieson BSC – a more capable substitute you could not imagine.

As far as Mathieson can tell, he got the gig following recommendations from co-producer Max Keene, gaffer Chuck Finch, and camera operator Chris Plevin – all collaborators with Ritchie on Sherlock and each with connections to Mathieson, the two time Oscar nominee (Gladiator, The Phantom Of The Opera), through their work together on films such as 47 Ronin, Robin Hood and Kingdom Of Heaven.

“I kind of got the show by way of a few references and the misfortune of a fellow DP,” explains Mathieson. “It came rather quickly and the technical crew and much of the key decision-making was already in train.”

The timing wasn't ideal for this avowed enthusiast for film. In early 2013, in the wake of the pending closure of Technicolor's processing lab at Pinewood but before Deluxe-owned Company3 joined with iDailies, and long before Disney landed Star Wars in the country, UK film processing was on the verge of collapse. “There wasn't a choice about U.N.C.L.E.'s shooting format, we had to shoot digital,” he says.

Mathieson had shot with REDs and ARRI Alexas previously but doesn't favour one over another, viewing all digital cameras as essentially inferior to negative. “I couldn't really care if I never saw a digital camera ever again,” he says. “With digital you don't have to be a craftsman. You can shoot and add colour and exposure in hindsight rather than sculpt instinctively in stone. But U.N.C.L.E. was not a bad project to do digitally. Digital cameras will give you synthetic primaries, rather than burnt Renaissance painting colour, but then this is a Sixties’ pastiche comic-strip with bright, bold colours. So I thought, 'let's just go with it and not be a Luddite about it’.”

Principal photography began in September 2013 on Alexa XT with some B-roll shot on GoPro Hero (unused in the event). Canon EOS 5Ds proved more useful for stunt sequences, including one which resulted in a car being submerged underwater. “We sank the vehicle and couldn't retrieve the footage until a week later but it was perfectly serviceable,” he says.

Like Ritchie's Sherlock Holmes films and his 1998 feature debut, Lock, Stock And Two Smoking Barrels, The Man From U.N.C.L.E. inhabits a world of both flash and toughness. The director largely left Mathieson to his own devices, concentrating on working with the actors rather than engaging his cinematographer in animated shot-by-shot conversation or suggesting a definitive look.

“We tried to tip our hat to the period,” says Mathieson. “We shot mainly with Panavision E Series Anamorphic primes and older Technovision spherical lenses, which all had the feeling of the time. They possessed aberrations and a fogging or veiling which helped to set the film back, not as far as the Sixties, but certainly a throwback to the past.”

"You couldn't really cut directly to the Alexa. It's about bending the format to taste. This the look of the 1960s from a 2015 lens"

- John Mathieson BSC

Other glass included an old Cooke Cine Varotal MKII 25-250mm T3.9 zoom, Cooke Varotal 40-200mm, an Elite zoom 240-1040mm and Cooke Varotal T3 for night work.

The closest filmic references for The Man From U.N.C.L.E. were the early 007 James Bond movies of Dr No (1962) and From Russia With Love (1963), both shot by DP Ted Moore BSC. “A lot of the look of those films was achieved in the styling – of two-tone suits, jet-black waxed hair and skinny ties with girls in polyester dresses and classic cars, but the look was quite colourful too,” observes Mathieson. “The film stock of the time is quite rich and contrasty with strong blacks and deep colours. That's not quite so easy to achieve on digital.”

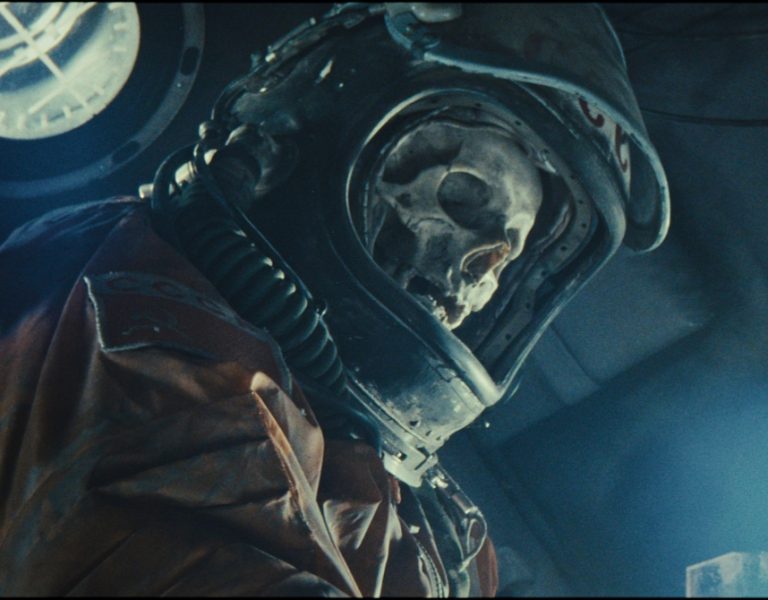

Some 16mm Bolex negative was shot as a transition between the title sequence, containing scene-setting newsreel of President's Kennedy and Khrushchev during the Cuban missile crisis, “to bring us into the digital world as gently as possible,” he says. “You couldn't really cut directly to the Alexa. It's about bending the format to taste. This the look of the 1960s from a 2015 lens.”

Mathieson's lighting package was generally in keeping with the period, mainly met with Tungsten 5K – 20Ks. “We were not using HMI, Kino or LEDs. The Sixties had a lot of fantastic design conveying an opulence and optimism about how things should be, but the computers in our world flash like car indicators. It's not high-tech. The palate for this film is colourful and warm and we felt Tungsten lamps suited that mood. We'd probably have gone with LEDs and fluorescents if we were shooting a more modern type of film.”

Although some Steadicam was deployed, the period nature of the piece lent itself more to track work. “I think we'd all rather track if we could,” he says. “In some ways it can be much quicker to work on set using tracks. It doesn't take long to run a track around and it means you can stop and interrogate a frame, talk about a shot, redress the set or adjust for lighting as necessary while the camera operator isn't bending their back.”

Being a Warner Bros project, Leavesden was the show's studio home supplemented with a considerable amount of location shooting. The Royal Victoria Docks near London's City Airport was a mock-Mediterranean harbour. An old mill near City Airport and derelict buildings at Chatham Docks provided a backdrop for bombed-out East Berlin. A scene set under Brixton's railway arches was used for “spies coming out of greasy garages exchanging packages, picking up fast cars”, and Greenwich's Maritime Museum doubled as Berlin and the backdrop for a car chase. Various London interiors in keeping with the ‘60’s period were also used. A café was specially-built in Regent's Park.

The mission itself begins in Italy on location in Rome, Naples and Neapolitan islands, including interiors of large municipal buildings of the La Dolce Vita period “with shiny floors, columns and lots of glass. A certain degree of elegance you wouldn't get anywhere else,” Mathieson recalls. “We shot in the Grand Plaza hotel near Rome's Piazza del Popolo which we just shot for what it was – falling down rococo with old-fashioned décor, a wonderful staircase and reception areas.”

The Alexa data was handled by DIT Francesco Luigi Giardiello on-set and on to Technicolor for post, using the Codex workflow, but Mathieson professes to be more interested in getting the images right and controlling the final look than the technical process that happens in between.

“If you give it the right exposure you can achieve a very different feeling within the same lens,” he says. “If you want a hard look or a soft, swimming look with flare you can do so within the iris. Some of the older zooms have had their front elements taking quite a beating which was great to play with.”

He continues: “When you look at the Log or at the RAW image in digital it's horrifying, but you want to make sure the images are as good as graded rushes. When things are in editorial the scenes will move up and downstream and the story arc and time of day will change and, therefore, so will the look. You might then have to soften the lighting to move from a dawn to dusk scene.”

He worked with colourist Paul Ensby over ten days, locking the picture down by summer 2014. “I'm not someone who spends hours in the grade finessing each detail. I view the DI process as a piece of music with shades of fortissimo and mezzoforte and that the more you tinker with the image, the more you risk ruining its rhythm.”

He says, “The way I like to grade is to take the best shot in a particular sequence then grade around that, rather than trying to add in windows which just tends to average everything out. Maybe the end result is rough around the edges, but I'd rather have that than a piece which is bland and boring. I got it to where I wanted it to be. But I would have made it look better on film.”

This from a craftsman who learned his trade on U-Matic and BetaSP before graduating to film. “It's a great shame that there's a generation of kids who have never had a chance to try 16mm. Now everyone graduates to shoot digital. Even if they want to shoot film they are not given the confidence to expose film.

“We're talking about the key craft skill of using one's eye to judge exposure, to really look at the light rather than looking over your shoulder at a monitor with a waveform and vector scope before pressing a record button.”

He adds: “I can't tell the difference between the looks of a lot of the big VFX films. Did any cameraman put their stamp on it or even design it?”

Mathieson is well aware of the irony of currently filming the hefty CGI fantasy Knights Of The Roundtable: King Arthur, also for Ritchie, back at Leavesden.

“There is a place for massive stories told in VFX using a computer, but the sadness is that we've lost a generation unable to make the leap to shooting film,” he says. “I could teach twenty students how to light for greenscreen in just half a day. When I shoot greenscreen my arm is tied behind my back and I just glaze over since my input is redundant. If I sound disillusioned, I'm afraid that's how I feel.”