Constant Gardener

Ellen Kuras ASC / A Little Chaos

Constant Gardener

Ellen Kuras ASC / A Little Chaos

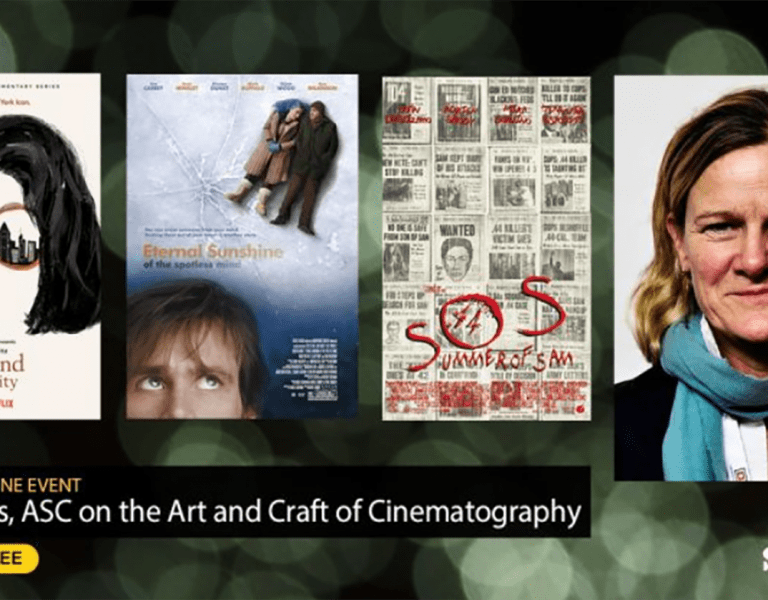

Ever since Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind (2004), cinematographer Ellen Kuras ASC and actress Kate Winslet have remained close. So when a period drama starring Winslet came across Kuras’ desk – never mind the fact that it was Alan Rickman’s first time directing since The Winter Guest in 1997 – it was only natural for the two women to come together again and create beautiful art.

A Little Chaos, which premiered at Toronto Film Fest last year and releases this April in the UK, is about the fictional Sabine De Barra (Winslet), a female landscape-gardener – a profession dominated by men – who is awarded the esteemed assignment to construct the gardens at Versailles under the guidance of real-life character Andre Le Notre (Matthias Schoenaerts), a job that lands her at centre court of King Louis XIV (played by Rickman).

“I was entranced with this script,” says Kuras. “I loved how Le Notre was a real person in history who actually thrived in Louis XIV's 17th century France, yet Sabine is an imagined character who perhaps embodies the feminine side of him. To me, she manifests the wild, the untamed, and the emotional aspects of ourselves that exists in nature - male or female. She is nature personified. For me, one of A Little Chaos' central themes is man versus nature as re-interpreted and re-envisioned by a woman who is Sabine.”

Rickman, a prolific actor since the 1980s, now again in the director’s chair, had specific ideas that he relayed to Kuras about how he wanted the story to feel and the sensibilities of the film. At their first meeting, which happened in a stroke of luck when both Kuras and Rickman were in New York (Kuras had only been sent the script that afternoon) she brought along Sally Mann’s “Immediate Family” photographic tome, which inspired her in how the spirit of Sabine’s child, could be created visually throughout the story.

“Alan responded to the textural and emotional living in those images much in the same way as I had, so we got on the same page really early on,” Kuras says. “He’s such a visionary; he has a certain way of seeing and inhabiting the world that is very unique. He has a dual perspective of being both an actor and being a director, and also of being a true visual artist who can draw expressively and appreciate the feeling that comes from the look of a photograph, not to mention his incredibly engaging sense of humanity and humour."

Given the low budget of the film, it would have been impossible to try and emulate the grandeur of locations like The Louvre or Versailles. In order to effectively have Rickman’s visuals come to life, and be communicated to key crew back at the locations in the UK, he travelled with Winslet, Kuras, production designer James Merifield (Austenland) and the producers outside of Paris to Versailles for a personal tour.

“We wanted to feel what the light felt like coming in through windows,” Kuras describes, “the scale of it all, how the rooms were set up, how the King’s bed was so high. French court society was very particular in the way life was divided. Being there, we could stand in the exact place where the King would have been sleeping with half the court standing there watching him. How wonderful it was to be there to feel these strange juxtapositions of court life, informing our perceptions of what court life was really like.”

Only the interior of Sabine’s house and the exterior of her garden were built and shot on a stage at Ealing Studios. Otherwise, they shot mostly at practical locations – palaces and manors outside of London – Blenheim Palace, Waddesdon Manor, Henry the VIII's Hampton Court Palace. Because it’s a story that takes place in the 17th century and both Rickman and Kuras come from a film background, they wanted to impart that feeling inherent in celluloid.

“I feel that film has the quality of being more 'round' and having more depth than digital,” says Kuras, who often shoots on and enjoys the ARRI Alexa. “I could achieve a more emotional sensibility with film, but as a technician working at a time when film is transitioning, it was not an easy choice to go with film. The technical lab support is no longer consistent and the choice of film stock is vastly limited compared to even three years ago. Both Technicolor and Deluxe closed their labs several weeks before filming began, so I had to deal with inconsistent processing of the negative at an inferior lab, yet we decided to continue to take the extra steps to shoot film because we wanted to capture its unique textual feeling."

“Normally,” adds Kuras, “a lot of diffusion might be put in front of the lens for a 17th century drama. Conventional filtration seemed counterpoint to what Alan had expressed in the desire to keep the film relevant and have a contemporary story in a 17th century setting. Meaning that he not interested in making some rarified period film with little relevance for today. He wanted to temper the look so that audiences would listen to what was being said and acted. I took that to heart.”

Kodak Vision3 500T 5219 was the workhorse for night exteriors and interiors, as it was the only high-speed stock available. The Vision3 250D 5207 was used for the interiors of palaces, since it’s greater sensitivity allowed fewer lights for shooting inside the palace locations, which was quite restrictive due to original antiques, tapestries and textiles still in place. These organic materials are very sensitive to heat and light, so most locations had minders with very sensitive light meters to count every single lumen in a given room. The slower-speed 5213 stock gave the day exteriors and interiors a richness of colour and depth.

"I feel that film has the quality of being more 'round' and having more depth than digital."

- Ellen Kuras ASC

For dailies and post-production, Kuras was limited in her choices of post. Although with longtime relationships at Technicolor, Deluxe and Company 3, she was at Lip Sync for the grade and other post-production, due to an equity deal that was in place in London before Kuras came on the project. Rickman was present for the grade, supervising the last week when Kuras had to return to the US for another project.

“Our UK crew was fantastic in every department,” Kuras says, reminiscing on their time together in these ornate yet challenging locations. “In the camera crew, lead first assistant and focus puller Ian Struthers, and second assistant Ryan King were by my side every second of the way. Gaffer Johnny Colley and his best boy Darren Harvey streamed light in palaces and managed a tricky schedule with the birth of Colley's first baby the day before principal photography began. Key grip David Maund kept the camera and crew literally smoothly moving above ground through knee-deep mud, and Stuart Howell brought his lovely eye to framing the B-camera as well as the second unit photography.

Kuras laughs when she gets the question again about being a female cinematographer, because it has become a rhetorical question for her. "I don't dwell in the gender discussion," she muses because she’s convinced that women actually have a little-advertised advantage in the world of cinema, the purveyor of feeling.

“Women are said to be more emotional than men, who might tend to be more analytical,” she says. “So instead of being defensive about the tendency to the emotional, I've realised that I can tap into this feeling and the ability to interpret the emotional into a technical, visual medium – which is supposed to convey emotion –and use it to advantage. I would rather focus on the work itself rather than on the gender of who is behind the camera. For me, it’s all about the meaning of the story, and how meaning is expressed through the photography.”