STILL SHOOTING

Clapperboard / Douglas Milsome BSC ASC

Still Shooting

Clapperboard / Douglas Milsome BSC ASC

BY: Ron Prince

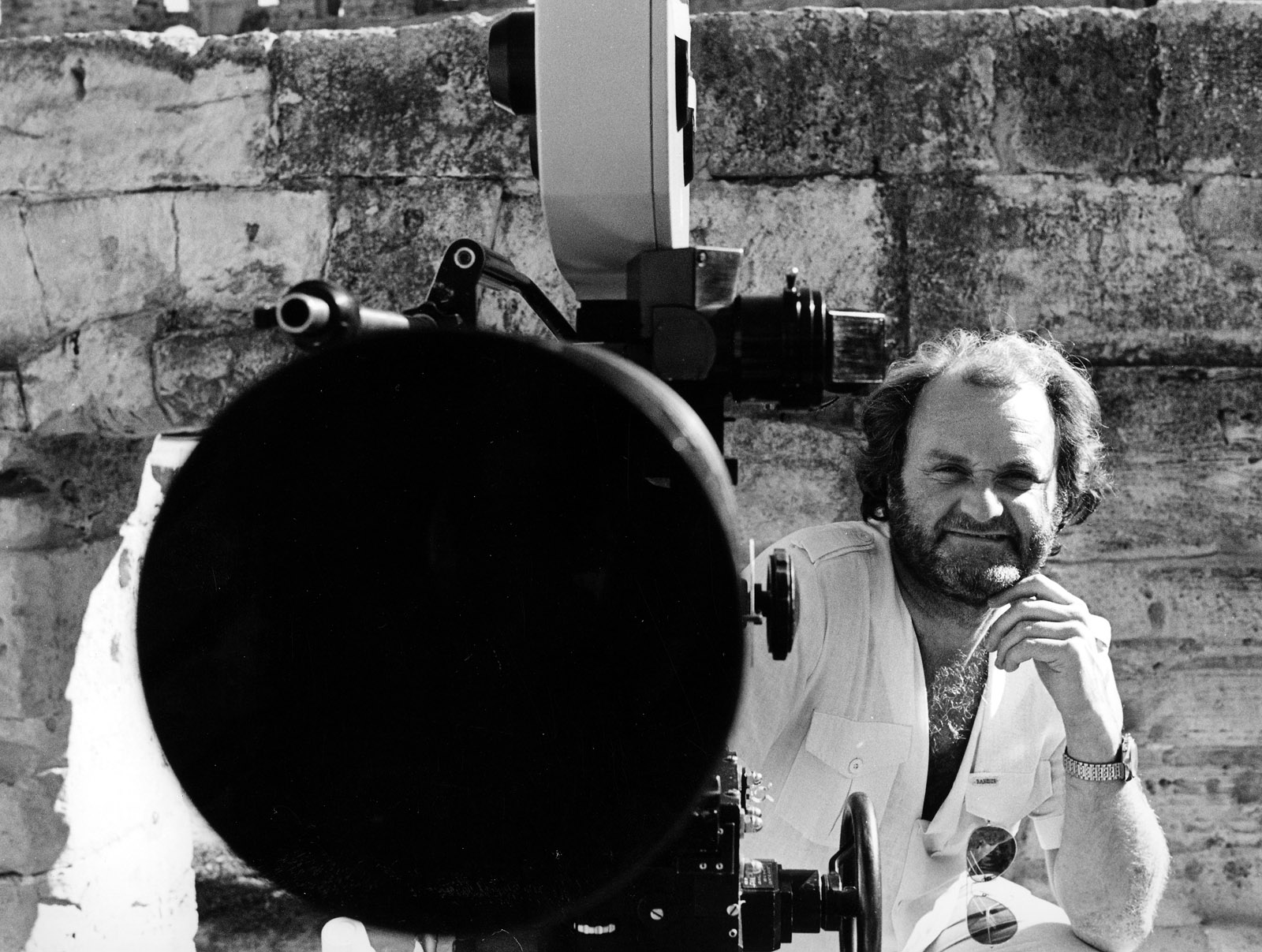

Whereas others might have retired long since, Douglas Milsome BSC ASC, now aged 81, continues to enjoy filmmaking more than ever in a stellar career spanning over six decades and more that 60 long-form narrative credits as cinematographer.

"I'm about to shoot Kingslayer in Scotland, in October, Covid-permitting, for director Stuart Brennan," says Milsome. "I told him, 'I'm old, mate.' He said, 'Are you sure? Bring your eye!'"

Born in 1939, in Hammersmith, London, from modest beginnings he rose from focus puller to camera operator and then cinematographer, working along the way with some of the world's most renowned directors and respected DPs, most notably Stanley Kubrick and John Alcott BSC.

Milsome became a member of the BSC in 1987, the ASC in 2001, and was accepted as a member of the Academy Of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences for "demonstrating excellence" in his work. Tragically, Milsome's son, Mark, also a camera operator, was killed in an incident during a shoot in 2017, and the venerable DP is on the board of the Mark Milsome Foundation, and continues to press for justice for Mark.

By kind permission, Milsome allowed us to publish some of his fascinating recollections about his early moviemaking career.

"Upon leaving a working-class school, aged 16, where I achieved only average grades in most subjects, I undertook to not end up like my father - cleaning carriages for British Rail at Old Oak Common. My mother, though, designed and made haute couture dresses for a leading fashion house, and I counted on inheriting some of her talent, albeit in a different artform.

I suppose like a lot of fellow photographers, my early career interest began from having a stills camera. A second-hand Rolleiflex, with an F2.8 Tessar portraiture lens, aroused in me endless interest and satisfaction.

In 1956, I answered an ad to assist in the camera section of commercial advertising company, Rank Screen Services, based in a small underground studio in Hill St, London, W1. They had a couple of 35mm Bell & Howell cameras and a Mitchell Standard 35mm rostrum-rigged stop-frame camera. During my 'temporary' stay, mostly making all the tea and coffee the camera operators could drink, and amid plenty of bollockings, I did at least get to load the magazines in the dark room, do dip tests, process B&W negative and log the lab reports.

In 1957, the company moved to a bigger facility, luckily me with it, at Pinewood Studios, where they had a much bigger rigged-camera layout department, with several more cameramen, and a fully-equipped model animation stage run by Tony Thompkins, an accomplished and clever DP, who I assisted. It was intricate and time-consuming work, but it was a good grounding and I learnt a lot.

Pinewood was big, with many major feature films in production, and a huge camera department with resident camera crews, who I had a chance to meet on-set. I had the privilege to learn from and assist people such as John Alcott BSC, Alec Mills BSC, Jim Devis, Steve Clayton and John Morgan, on my journey through the crew system.

After three years at Rank Screen Services, earning £4-a-week with the required ACT ticket, I entered the freelance world, thinking, 'This might be an uphill shit-fight, but I will enjoy it.'

For a while it seemed that I had screwed up by leaving Rank, but Les Smart, head of camera at MGM, helped get me my first movie job, The Doctor's Dilemma (1959, DP Robert Krasker BSC). The camera - a Mitchell NC with soundproofed blimp and a side-mounted auto-parallax viewfinder - was operated brilliantly by John Harris.

I then went on to Expresso Bongo (1959, DP John Wilcox) shot in 35mm B&W, where the Dyaliscope lens system needed two focus pullers for each lens. John Wilcox later took me to Rhodes to shoot second unit on Guns Of Navarone (1961, DP Oswald Morris BSC) in Panavision 35mm using the first combined Anamorphic lenses.

I got back to home after many weeks away, only to be greeted by regimental police - I was amongst the last intake of National Service Army conscripts. After six weeks of basic training, I married Debbie, only to get back from our honeymoon AWOL, and be slung in the growler/military clink. But I got my wings with a compassionate posting in the Army Kinematograph Service, shooting aerial reconnaissance and recruitment films with a 16mm Bolex. I was de-mobbed in 1962, with Debbie pregnant with Mark, and I started back in the business.

That year I worked as the only loader between four ARRI 2C cameras, shooting a pack of hounds in a stag hunt near Dublin for John Huston's The List Of Adrian Messenger (1963, DPs Joseph MacDonald/Ted Scaife), which got me back in shape after two years of National Service.

Many films followed. One I will always remember Never Put It In Writing. In July 1963, we were filming at Shannon Airport, when a light Proctor aircraft lost control and crashed into our Buick shooting-break camera car.

The DP, Dave Bolton got it worst - fractured skull and lost an eye from the propeller that feathered splintered wood and glass. Virginia Stone, the director's wife had both legs broken. I got stitched up, whilst Tony Spratling BSC luckily escaped serious injuries. Mark, our son was two months old, at the time. It is ironic how things can work out.

There then followed Henry Hathaway's Circus World (1964, DP Jack Hildyard BSC) shot in Technirama, using a Vista Vision 8-perf camera with a quarter Anamorphic squeeze. It took 2,000ft mag loads, and with a 22'' Mitchell geared head, needed four grips to lift it - so there wasn't a lot of handheld done!

After months of loading on Casino Royale (1967, DP Jack Hildyard BSC), I got a break to pull focus on Michelangelo Antonioni's Blow-Up (1966, DP Carlo Di Palma), thanks to Alec Mills BSC who thought I was ready, and who moved up to work as an operator on another show.

This was Michelangelo's first English-language feature - an intriguing, if self-indulgent, challenge to the idea that the camera never lies. I appeared to fit in well with Carlo the DP, despite English not being exchanged much on-set and constant Latin tantrums. Ray Parslow, the operator, spoke fluent Italian, and he reassured me "You're OK, you're not getting fired!" Actually, getting on well with the movie's star, David Hemmings, would open-up other opportunities in the future.

After ten years as a second AC, I was now established as a 1st AC. Although I worked on many features over the next 16 years, perhaps the most interesting experiences, and steepest learning curves, were with John Alcott BSC. He always struck a chord with a look, technically pushing the envelope. John was the 'Prince Of Darkness', that never actually looked dark. With Lou Bogue, his gaffer, who kept the lighting package in a small van, it was often hard work for the focus puller, as the exposure was always at the toe-end of the widest lens aperture.

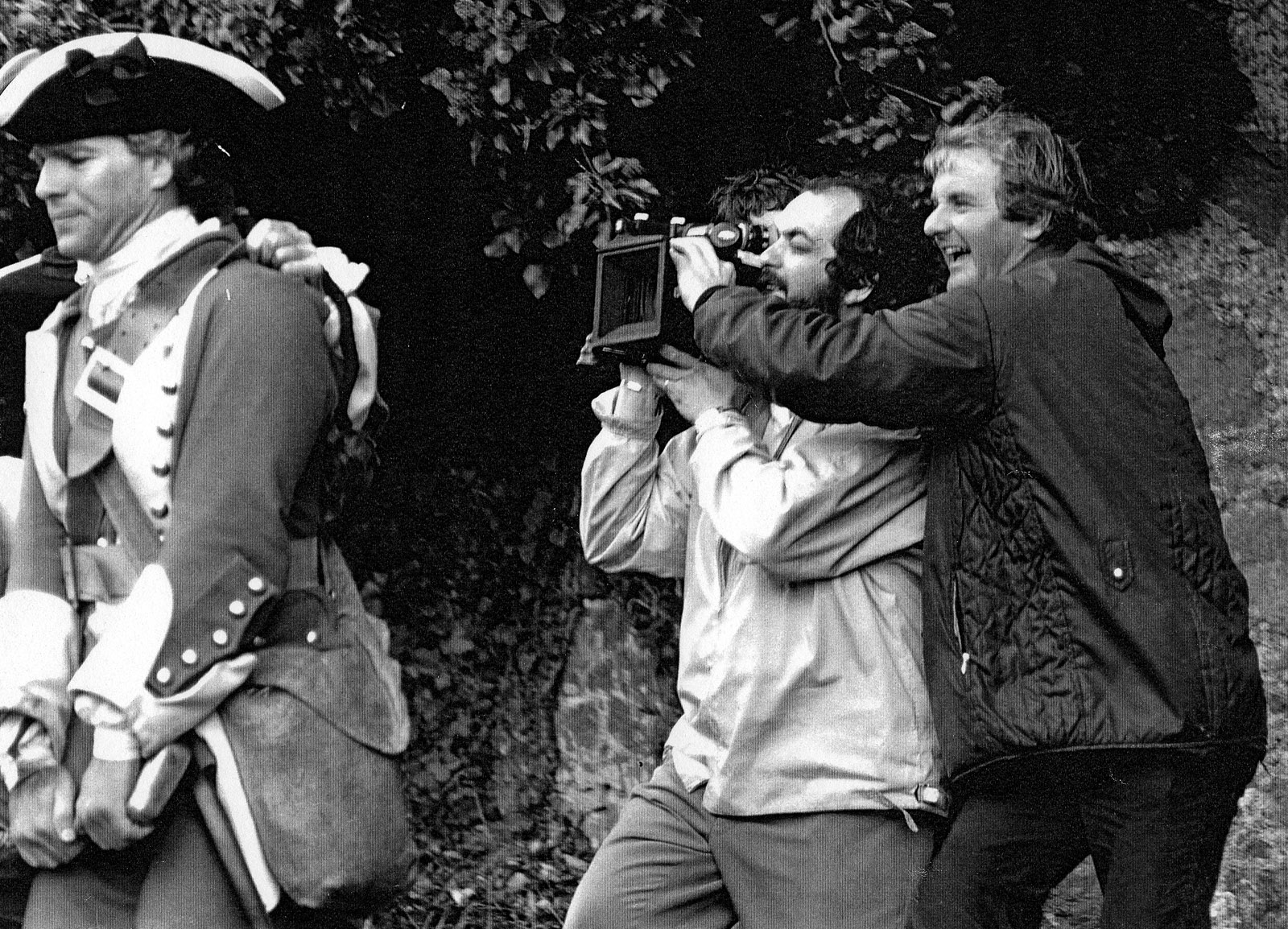

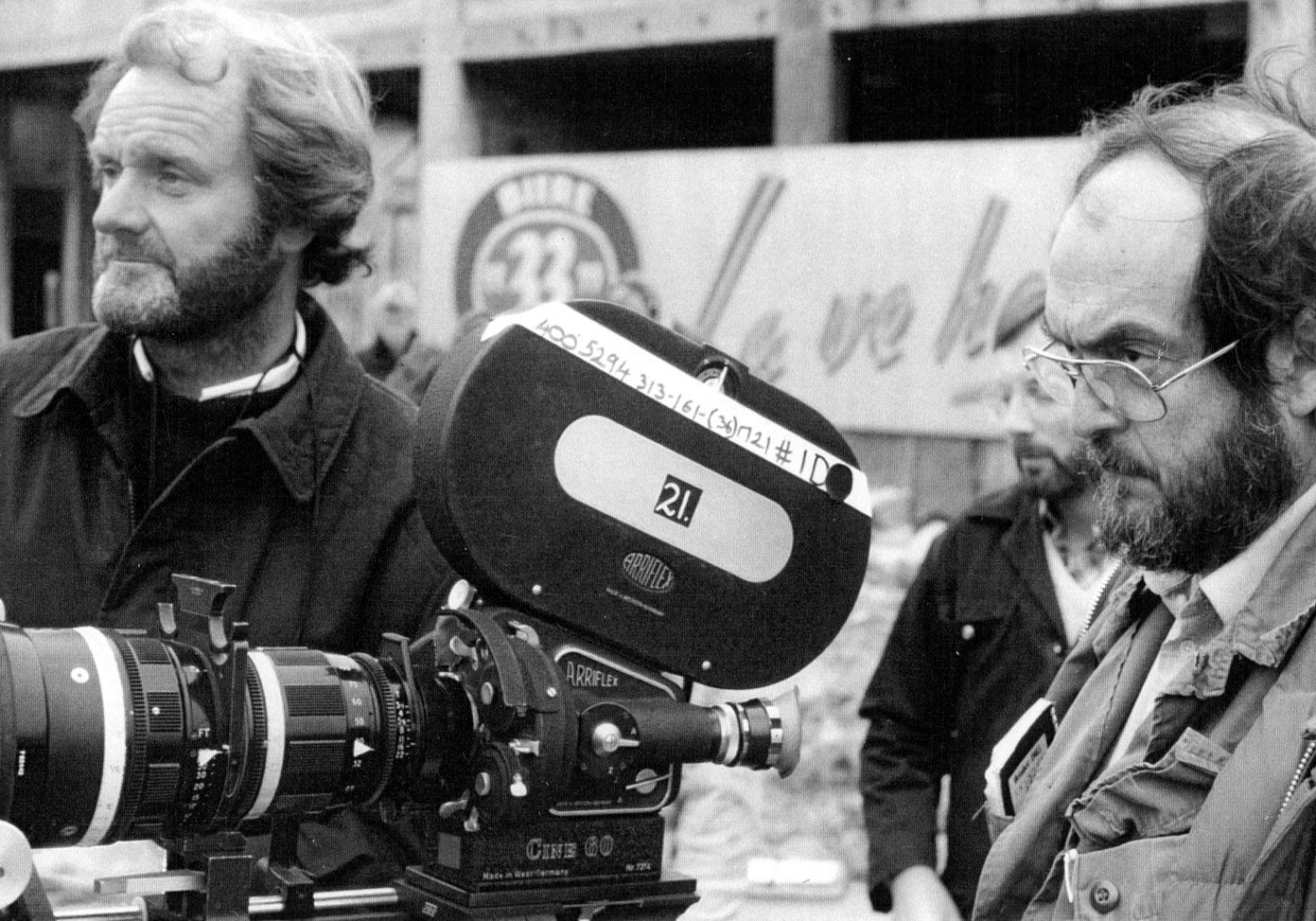

In 1973 I had my first encounter with Stanley Kubrick for Barry Lyndon (1975, DP John Alcott BSC). It was daunting, of course, being in the presence of greatness, and with his reputation preceding. Alcott briefed me beforehand in ego management. "Answer any questions with either 'Yes', 'No', or 'I'll check', and don't make excuses. He's a chess player, play the pawn. He's like a dog with a bone."

I was confident at this point, having many years of experience, and after working on Modesty Blaise (1966, DP Jack Hildyard BSC), Polanski's Macbeth (1971, DP Gilbert Taylor BSC), the storm sequence in David Lean's Ryan's Daughter (1970, DP Freddie Young BSC), The Adventures (1970) and The Horseman (1971), both shot by DP Claude Renoir.

It was Kubrick's idea to film Barry Lyndon in natural candlelight and the Carl Zeiss Planar lenses we used allowed us to shoot scenes lit only by candlelight on Kodak 5254 100ASA film. These lenses were designed and made specifically for NASA's 1966 Apollo lunar programme to capture the far side of the Moon on stills cameras. Stanley got four, all 50mm f/0.7, and then it became a long journey to adapt them to work on his blimped BNC Mitchell camera, before prepping all his other cameras - including the first ARRI BL, a high-speed NC Mitchell, plus two ARRI 2Cs and an Eyemo - followed by 70 of his other lenses. Including a year's principal shooting, this was a labour of love for a full 18 months.

However, the result evoked a genuine 18th century atmosphere of renaissance paintings and today still, in my view, it's the best collection of images ever assembled on a strip of celluloid The crown deservedly went to John, an honour I share being a part of.

To my relief, the Bond I did shortly after, The Spy Who Loved Me (1977, DP Claude Renoir AFC), with Lewis Gilbert directing and Alec Mills BSC operating, in Sardinia and Luxor Egypt, seemed an absolute vacation. This was followed by a six-month hoot on The Pink Panther Strikes Again (1976, DP Harry Waxman BSC), with the great Ernie Day operating.

In 1979, came The Shining (DP John Alcott BSC) - a much easier ride than Barry Lyndon. Some of my favourite moments were shared with Garrett Brown, inventor of the then little-known Steadicam. Kubrick called it his magic carpet. Garrett's brilliant use was a cinematic breakthrough, capturing the blunt symmetry of endless corridors, painted carpets, empty halls and doors. With this rig, he could run flat out with a 28lb 35mm BL camera, but keep the image rock steady.

My other favourite moments were being chosen to complete principle photography for a further seven weeks after John Alcott left the picture, and shooting the opening/title sequence in Oregon with Jan Harlan his producer.

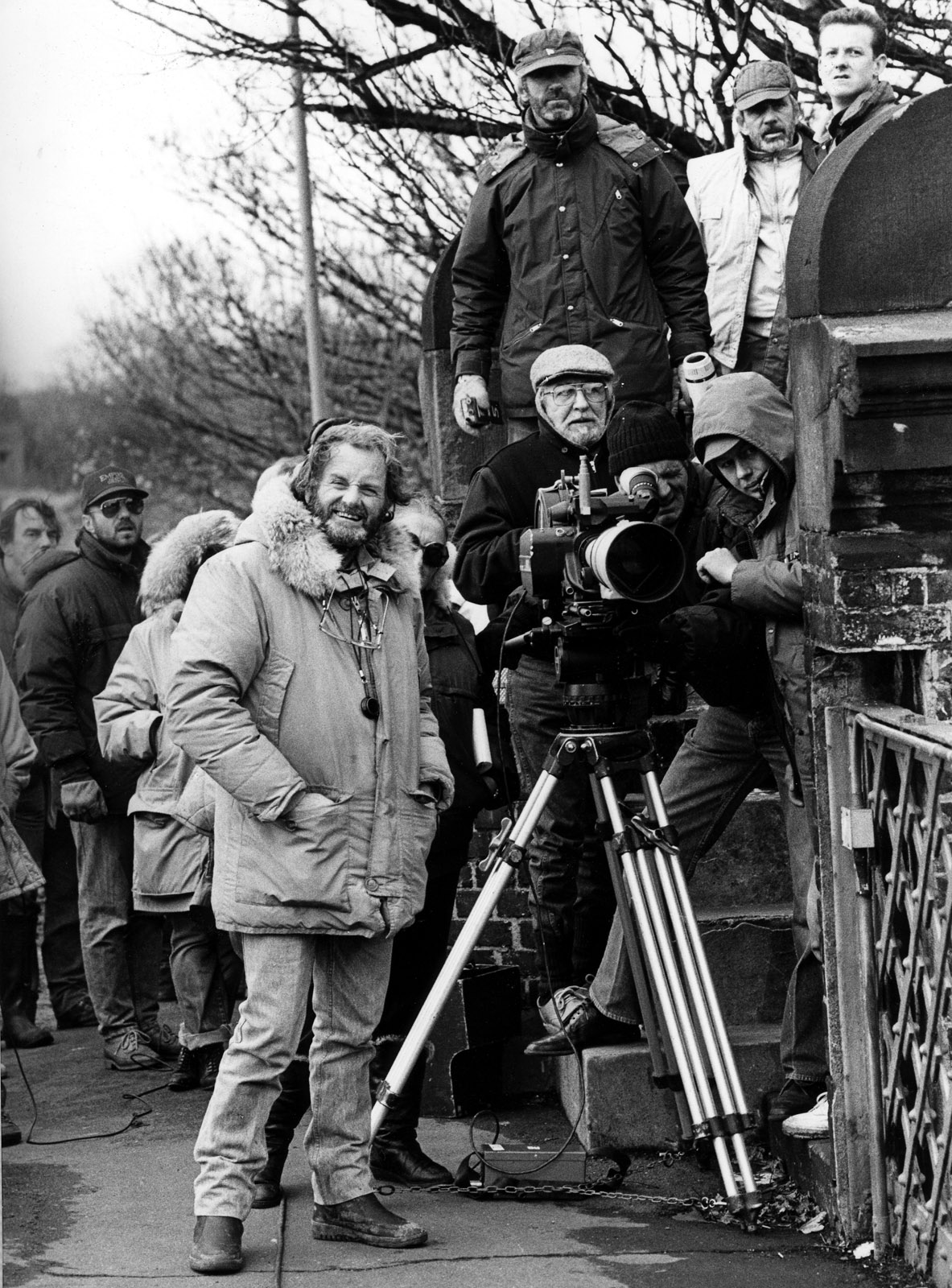

In 1980, aged 40, I decided to move up to operator. I got an offer from David Hemmings to shoot/operate second unit on the action-thriller Race To The Yankee Zephyr (1981, DP Vincent Montin), which he was directing. This proved to be eight weeks of hairy action - chasing jet boats from Hughes 500 choppers with a mount from Nelson Tyler in Queenstown South Island New Zealand. Other productions down-under followed including Wild Horses (1984), which I was asked to photograph. The Bounty (1983) came next, with the mission (if I chose to accept it) of shooting for four weeks on a 3,000-mile voyage across the South Pacific, and another three months shooting second unit on the island of Moorea. I later operated main unit on three films for different Australian directors - Bruce Beresford's King David (1985, DP Don McAlpine), Fred Schepisi's Plenty (1985, DP Ian Baker) and Highlander (1986, DP Gerry Fisher BSC), directed by Russell Mulcahy.

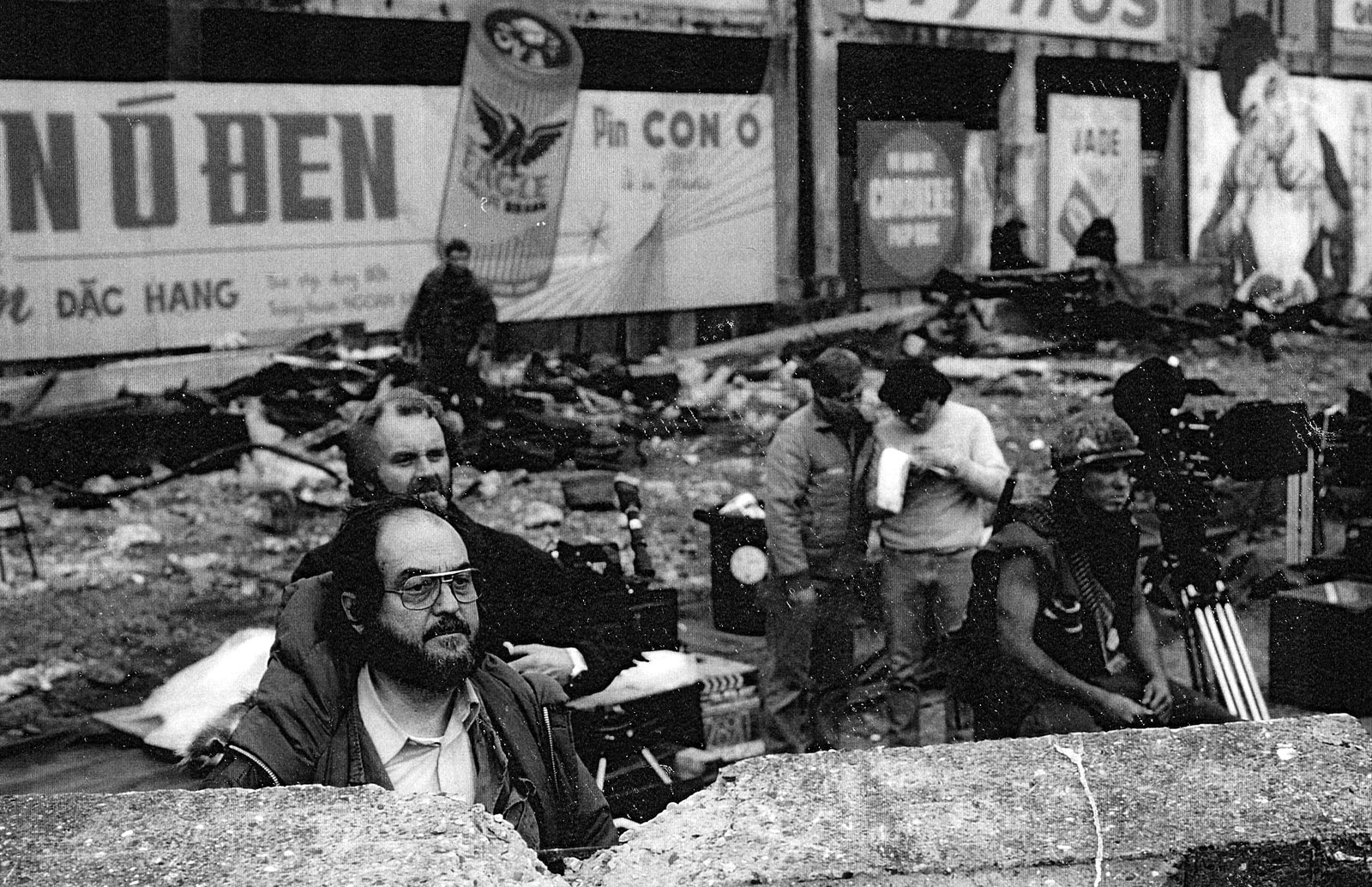

In 1985 came the invitation of Stanley to shoot his Vietnam epic Full Metal Jacket (1987) as the cinematographer. It was a long, tough shoot for all the crew, and especially for me in making Stanley think he had made the right choice in me.

Stanley's plan was to mold his actors into a form he imagined as altruistic on one hand, born-to-kill aggressors on the other, creating a sense of hopelessness - no heroes, no easy solutions, no happy ending.

Anton Furst, the production designer, reduced Beckton Gas Works to rubble, planting palm trees in skips for sub-tropical effect, to fulfill yet another idea of Stanley's to transform South East London the South East Asia. Adam Samuelson's Louma crane was mounted on a low-loader, always ready to spring into action. Jonathan Taylor, my first AC, had enough technical training to stand up to Stanley's constant inquisitorial barrage. Lovely John Wards was on Steadicam. I, myself, having learnt to become the instrument of Stanley's vision, was trusted to operate the camera for him, always with a geared head.

We shot Full Metal Jacket with fast, low contrast Kodak film, pushed a stop, and heavily ND-filtered, which increased grain and desaturated the colours. It was a study in grey/green backlight, with smoke to help evoke the mood of urban warfare.

I carry lots of personal memories of Stanley, and his films are a living memory of his status. I think he made movies to get through a case of chronic anxiety disorder. He was never happier than being behind the camera.

As a cameraman, I tried to reflect his personal authorship - a perspective that becomes open to interpretation - of letting the photography be true to the narrative, with the camera movement not in the way. Over the years, I must say that I had a harder time from far lesser talented directors than Stanley, who have been dogged by arrogance.

I went about finding distractions when Mark died. My sanity and health failing at that time, and despite two replacement knees, I took on small projects to film. Eve (2019) was an interesting, very low-budget, psycho thriller, with a bunch of refreshing young talents. Another I took was House Red, as it was shooting in beautiful Tuscany. I was supplied with a gift camera package, thanks to Movietech's John Buckley for that.

Mark Milsome's inquest takes place from 19th to 28th October, in a public hearing at The West London Coroner's Court, Fulham. We are up against the big guns of the BBC/Netflix represented by Weightmans, one of the biggest law firms, ready to eat us for breakfast. We have secured a lawyer with effective counsel in place for a fair hearing."