THE NEW WORLD OF WAKANDA

Returning to Wakanda following the death of its beloved king to tell a tale that is epic and intimate demanded writer-director Ryan Coogler create a sequel that is both a poignant portrayal of grief and a tribute to Black Panther’s leading actor. Joining forces with Autumn Durald Arkapaw ASC and a crew who were devoted to cinematic storytelling, they crafted a film with a unique identity that views loss through a new lens.

When Autumn Durald Arkapaw ASC read the script for Black Panther: Wakanda Forever and discovered the story writer-director Ryan Coogler (Black Panther, Creed, Fruitvale Station) and co-writer Joe Robert Cole set out to tell included a whale jumping over a bridge, it offered an early indication of the film’s soaring aspirations. “This movie is so ambitious, as it should be,” says the cinematographer. “Ryan dreams big and to be on set with him, to realise these dreams with him, was very rewarding. I’d do it again in a heartbeat. This film made me want to continue approaching stories and concepts that are bigger while also making them feel intimate.”

Rachel Morrison ASC, who lensed 2018’s Black Panther, was unavailable to shoot the sequel because she was directing Flint Strong, so she recommended Coogler collaborate with her fellow cinematographer and friend Durald Arkapaw (Loki, The Sun Is Also a Star, Teen Spirit). The timing was perfect for Durald Arkapaw – who was “already a big fan of Ryan’s work” – as she was finishing shooting Marvel series Loki when she received the call.

Having taken two months off after wrapping Loki, Durald Arkapaw began nonconsecutive prep with Coogler in February 2021. Although having not yet met, the pair instantly clicked, and Coogler invited the cinematographer to get involved in the early pre vis he had begun. “There was so much to do, it was pretty insane. I ultimately worked on the film for more than a year and a half,” says Durald Arkapaw.

“Chadwick [Boseman] had passed, and I was already aware when I came on board that the script would be revised and that it was important for Ryan that there was this through line of grief. He was great at giving soulful insight into what he felt this film should be and what Chadwick’s character T’Challa leaving meant for the family, the culture, and Wakanda.”

Continuing Black Panther’s narrative, Wakanda Forever sees Queen Ramonda (Angela Bassett), Shuri (Letitia Wright), M’Baku (Winston Duke), Okoye (Danai Gurira) and the Dora Milaje (Marija Abney) fight to protect their nation of Wakanda from intervening powers in the wake of King T’Challa’s (Chadwick Boseman) death. When Namor (Tenoch Huerta), king of a hidden undersea nation, alerts them to a global threat and his disturbing plan to thwart it, the Wakandans join forces with the help of Nakia (Lupita Nyong’o) and Everett Ross (Martin Freeman) and forge a new path for the kingdom of Wakanda.

“Ramonda realises that it’s been a year since T’Challa’s passing and Shuri’s still not healing—she’s not taking steps to move forward in a healthy way,” says Coogler. “They take a retreat—stepping away from the city, from the technology—to sit with no distractions and perform what is essentially a grief ritual. That’s when Namor shows up.

“We were really excited to explore the relationship between Ramonda and Shuri. The first film has a lot of father-son dynamics—both the protagonist and antagonist had to deal with moving on after his father passed away. This film very much became a story with motherhood as a motif. So often moms have to continue to mother through difficult situations.”

When Boseman passed away in 2020, the filmmakers carefully considered what the next film and its narrative could be. King T’Challa was the heart of Black Panther —and Boseman remains in the hearts of everyone who worked alongside him including director Coogler. “Chad’s passing affected filmmakers and the actors in a way that was incredibly profound,” says Coogler. “Chad was very much our artistic partner in this project, in this franchise and in this storytelling. I would spend time with him, just he and I, talking about where we wanted to see the character go, where we wanted to see the story go, how much he admired the other characters and the actors that portrayed them. We realised that it would only be right for us to continue the story.”

Many discussions between Durald Arkapaw and Coogler about making Wakanda Forever centred on character and emotion and the “deep feelings audiences would experience when watching the film”. The cinematographer found this more helpful than being sent references outlining what Coogler wanted the film to look like. As well as exploring how people deal with grief and overcome loss, and “how it can feel like a dream, and a layer of fog over your sense of who you are,” Coogler emphasised the importance of the migration of the cultures at the heart of the story. “We delved a little into the Mayan culture,” says Durald Arkapaw. “And the film is essentially multiple movies in one because it also introduces a big new underwater world.”

Accomplishing such ambitious set-ups required detailed planning and collaboration with the costume and production design, SFX, and VFX teams. “A lot of our time went into that upfront because for the underwater world, we had to build a tank and create costumes that react properly in water sets. Many stunts were underwater, and a big car chase sequence also demanded a lot of time in prep.”

One of the first scenes explored in storyboard form was the Wakandan bush sequence in which Shuri talks to her mother about how she is dealing with grief following her brother’s passing. “On paper that could look simple but it was important to Ryan that the scene was the core of the film. We then continued the nonconsecutive prep, a few calls a week, before my prep on the ground started in Atlanta in April 2021.”

A new lensing of loss

While conveying emotion was essential, films such as Alien and Terminator 2 also shaped the approach. “Ryan’s a cinephile and a big fan of those films, as am I,” says Durald Arkapaw. “They have so much texture, and even though there are visual effects, they feel real, and you feel for the characters.”

This approach aligned with the way the cinematographer likes to shoot and determined lens choice. Coogler, who had never shot anamorphic – Durald Arkapaw’s preferred option – was open to exploring new territory due to the texture and dreamy quality of the aberrations. “They’re very emotional, and that’s something he wanted to portray because it’s about which lens we’re using to look at this new world, and most importantly, to look at Wakanda without its king,” she says. “It shouldn’t be through the old lens, it should look different, because things have drastically changed, and everyone is mourning.

“The lead actor – the heart of the film – unfortunately passed away and the story was rewritten. It’s not about taking the first film, which was so beloved, and remaking that without him. The sequel needed its own identity – the format, camera, lenses, and DP was changing. And the way I shoot and see the world is very different to anybody else – every DP is different. I’m also a mother, a daughter, and I’ve experienced grief, so the story was personal to me too.”

Bringing a new cinematographer on board and changing the format was a sizeable decision for Coogler. His “strong and soulful” references determined that the lens needed a lot of character and texture and to convey a “fog of grief” through aberrations and flare. Having seen Durald Arkapaw’s work, Coogler was aware of her love for anamorphic shooting.

“He teases me about being anamorphic’s biggest fan,” she laughs. “I’m pretty much 99% a Panavision lens shooter so I’m familiar with their anamorphic glass, having worked with them since the start of my career. During testing I showed Ryan some T series and B series anamorphics that had been detuned and modified by Dan Sasaki at Panavision to look more like the C Series. Dan is accustomed to my sensibilities and how I embrace all of anamorphic’s qualities. This time I came to him with references like Alien, so the lenses have a nostalgic quality and a lot of personality which impressed Ryan. One lens in particular – the 35mm B series – was used extensively for many scenes and became our emotional storytelling lens which we shot many of our pivotal close-ups with.”

When shooting the IMAX sequences, Durald Arkapaw could not shoot with the 2x anamorphic lenses she adores as they cannot be used for a 1.9 IMAX deliverable. To gain more top and bottom, she used 1.33 squeeze Panavision Ultra Panatar anamorphic lenses which have similar characteristics to the main format used but can cover an IMAX deliverable. “It was important that stayed consistent when the aspect ratio changes as even though we didn’t shoot true IMAX, I didn’t want those sequences to feel different and bump,” she says. “And as the Sony Venice we shot with also covers the IMAX deliverable it was possible to film all sequences with that system.”

Family focus

Durald Arkapaw believes the production’s visual and narrative success is largely a result of Coogler’s direction. Combining the new underwater world with Wakanda was ambitious, but Coogler’s skill as a leader, and ability to “see everyone and be very collaborative but also clear about what he wants” was advantageous. Whether it was capturing an action sequence or an underwater scene, Coogler wanted to be involved in every part.

“His direction guides those who are creating the story and he wanted the visual language to be consistent,” says Durald Arkapaw, who thrives on taking on challenging productions that are outside her comfort zone, or bigger than her previous projects.

“The whole crew had a positive attitude when solving problems encountered while making such a huge film. Having someone like Ryan, who knows who they are and how to guide people on a set like this, is important. Directing is so many things, not just storytelling, and speaking to actors. At times, you’re a coach or a general, and you’re also sometimes a psychiatrist. To be all those things, and also be a family man and a friend to everyone around him, is impressive. And he does it with such grace. There can be frustrations on set and things can get pretty gnarly at times with the organisation of things, weather delays which in turn affect your schedule. But I would do it any day for him.”

It is fitting that a film focusing on family was directed by a filmmaker who appreciates the importance of maintaining a healthy work-life balance. “Ryan sees the importance of being there for your family and appreciates people have lives outside of their jobs, and that makes you feel better about giving a year and a half to someone who you’re trying to create art with,” says Durald Arkapaw.

While most of the film was shot on location and on soundstages in and around Atlanta, some sequences were captured in Puerto Rico. Durald Arkapaw and production designer Hannah Beachler – who won an Oscar for her work on Black Panther and collaborated with Coogler on Creed (2015) – wanted the scenes in Haiti and the Mayan flashbacks to feature a real beach that felt like it could be in those parts of the world. “Obviously, those beaches cannot be found in Atlanta, so, it was a big discussion to move a crew and cast to Puerto Rico which takes a lot of effort, time, and money,” says the cinematographer.

Discussions in prep determined which sequences would be shot on location, stage, or backlot. “I was involved early on in logistical discussions about the space and height needed and what size tank we’d have to build for the underwater scenes,” Durald Arkapaw continues. “I’d talk with my crew, because rigging is such a huge part of this type of film. Your rigging crew are the bones of the structure of your shoot because you’re constantly moving from stage to stage, and it must be rigged to fit in with all your ideas. Everything needs to be ready in advance so when you walk on set, you’re mainly lighting on the floor and adjusting.”

Playing a crucial part in creating the multifaceted world was Beachler, a production designer Durald Arkapaw considers to be bold and talented. “She’s so thorough in her research and infuses her ideas and designs with this research to stay true to the culture.”

For Wakanda, Beachler was tasked with expanding the nation, creating new, never-before-seen areas. “We’re going to see more of our capital city, our golden city. You can think of it like Manhattan, where you have the culmination of all of the different districts of the country in one place,” says Beachler.

“We get to see more of the day-to-day life of the normal Wakandans as well as North Triangle, the oldest place in all of Wakanda, which is inspired by ruins in Zimbabwe. We’ll see a little river town for the first time and more of Jabari. We also have new aircrafts for the Wakandan Navy that we didn’t have before.”

Sets that featured in the first film were approached differently, with new elements being added to spaces such as Shuri’s lab and tribal environments. “Tribal is a very strong set and people are very familiar with it, but it doesn’t mean the lighting can’t change,” highlights Durald Arkapaw. “Every DP lights differently and while some shots pay homage to the first film, as far as the lighting and lensing, we embraced a different look.”

Beachler was excited to rebuild Shuri’s lab which was blown up in the first film. “This time, we gave Shuri a vibranium-powered, floating elevator and we painted a beautiful mural on it,” says Beachler. “Her space has become a computer in total, so she very much has control of it – imagine it being like 4D. It’s my favourite set.”

Bold and brave

Coogler embraced a moodier tone and a braver look for Wakanda Forever, being ambitious with camera and lighting in a way which also aligned with Durald Arkapaw’s taste. “There’s tension and beauty in what you don’t see because darkness and the unknown can sometimes tell more of a story than seeing everything. You’re playing with the audience, using darkness to create mystery. There’s also sadness in darkness,” she says.

Balancing an action-packed story with more intimate moments was a pleasure for the cinematographer who “loves the intersection of drama with action”, having shot smaller indie films such as Teen Spirit (2018) in which a world is built around one protagonist and often filmed handheld.

“Ryan captures emotion so well and his characters are so full, so to have intimacy in certain scenes in Wakanda Forever was beautiful and grounded the film,” she says. “There’s so much of him in this movie and it’s so intimate and personal. But then you shoot a huge action scene which when edited has a life of its own but also feels personal. While the bigger fight sequence at the end of the movie has a lot of scope and becomes much broader – going from a ship to the Atacama Desert – even those epic scenes have a humanistic quality.”

For Durald Arkapaw, the film “was a dream come true” because she’s “always loved big action films, but not many female DPs are shooting them. So, to get the opportunity to shoot a huge movie such as this for Marvel – which are so far and few between – and with a director like this was incredibly rewarding. Having Ryan’s trust to execute something as big as this is also confidence building.”

Camera choice was integral in fulfilling Coogler’s ambitions and saw Durald Arkapaw work with the system she used to shoot Loki – the Sony Venice. “It was introduced to me by director Abteen Bagheri who I was working with on a Samsung commercial,” she says. “I’d never experienced a director falling in love with a camera that much. I then fell in love with it too. On that commercial I paired it with anamorphic Cooke Special Flare lenses and used a LUT created with Company 3 colourist Tom Poole. It turned out beautifully.”

As well as being impressed by the camera’s colour science, she was a fan of how it dealt with the shadows. “I like to sit my shadows pretty low,” she says. “You don’t want to introduce any digital noise, but you also want the shadows to feel filmic, so you don’t want heavy contrasts. I like a nice fall off and a soft shadow.” Being wowed by the combination of Poole’s LUT and the Venice, Durald Arkapaw shot more commercials with the camera, “working out how best to deal with highlights and lowlights” before Loki. “Loki was a great experience because it’s such a dark production, moody and mysterious, meaning a lot of our references were noir. So, I became accustomed to dealing with the shadows and the camera’s ISOs before Black Panther,” she says.

Connection with the character

While some directors allow the actors to fill the space and appreciate a quieter camera, Coogler “loves to have fun with it and move the camera.” Durald Arkapaw elaborates: “Ryan has good sensibilities and is very camera savvy. He has strong ideas about how he wants to cover things, where he wants to put the camera. Working with someone like that who’s very collaborative and open is fun.”

Durald Arkapaw tends to “centre punch” framing, believing this allows a better connection with the characters, as does sometimes “being a little lower on the eyeline”. Coogler also embraced the centre punched look for the film’s stronger frames. “When shooting anamorphic, it’s important you have a strong frame and the audience knows where to look,” says Durald Arkapaw. “We were shooting queens, generals, and important people and were working with a different format and bigger field of view to the first film, so it feels much stronger when people are in the centre of the frame.”

The cinematographer believes handheld has a place and is personal to the DP and camera operator. For each shot, she and Coogler examined whether handheld was the right tool and whether it would detract attention from the story or if Steadicam would be more appropriate. “For the opening sequence, which was one handheld shot, he really wanted to be with the character, so we worked out which were the best tools to achieve that.”

Having operated on previous productions, Durald Arkapaw operated some shots that were important to her because she wanted to be with the character. “Ryan appreciates that emotional connection an operator has with a character’s face,” she says. “I was excited to show him, and to connect with the character and the actor.”

Detailed pre vis was required, especially as some of the VFX sequences were fully CG, meaning it was vital to ensure the camera on set matches the pre vis for the next VFX shot. The cinematographer worked with A camera/Steadicam operator Jason Ellson and B camera operator Josh Medak. “Jason works with Mandy Walker a lot and had just finished Elvis,” says Durald Arkapaw. “He’s very collaborative and great on set at working with the grip team with the cranes. For some of our handheld work, he used a customised slingshot rig that’s smoother and more delicate than straight handheld.”

Guy Micheletti is “one of the most kind, fun and talented key grips” Durald Arkapaw has worked with: “His personality fills the set, but he also loves making rigs and worked with production to problem solve ahead of time, so I’m not affected when I’m trying to make decisions on the day.”

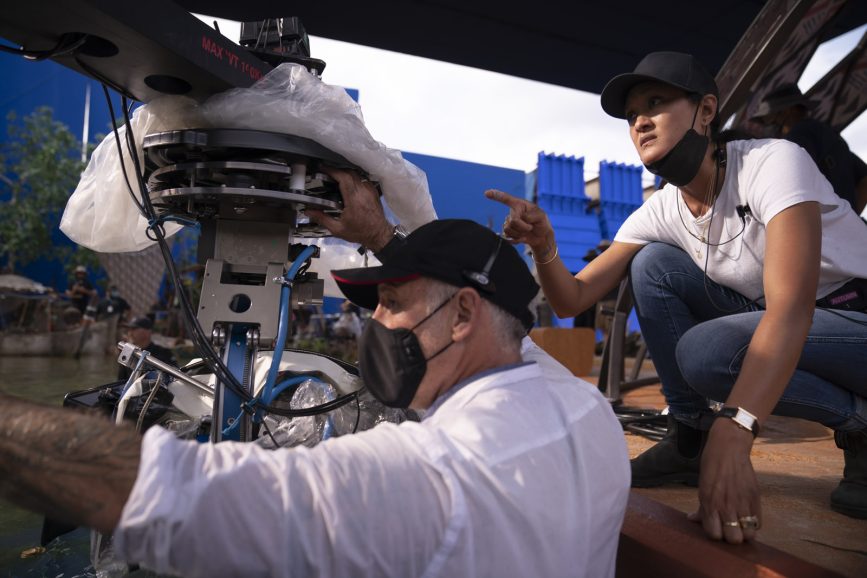

The camera crew worked with a vast arsenal of tools including a 73-foot Chapman/Leonard hydroscope with an amphibious underwater head and a 45-foot Scorpio telescoping crane to shoot the North Triangle flood sequence. “Ryan and I wanted to film a top down shot that tracks back with the procession of people. During the flood, when the crowd ran down the long road, the camera started far back and pushed in to a little boy as he is snatched up by Okoye. This was complex to tackle, especially with a crane in the water, and needed a great problem solver like Guy.”

Getting creative with colour

Talented experts in their fields including costume designer Ruth E. Carter (Black Panther, Coming 2 America, Selma) and production designer Beachler were engaged in in-depth explorations of colour. “Ryan also has amazing taste in fashion, music, and art and everyone on the team is very savvy when it came to discussing colour,” adds Durald Arkapaw. “A lot of the colour exploration starts with Hannah and Ryan’s discussion about the world, aided by the extensive research they did. Ruth also did so much research into what actually existed, and what was important to Mayan cultures.”

Carter wanted to honour Shuri’s emotional journey. “We knew this was a film about grief and loss and didn’t want to accentuate Shuri’s costume because the somber mood when she’s introduced was important to hold on to,” says Carter. “In the first film you saw her in brights. In this film, you see her in grays, somber colours… And then as she starts to develop through the storyline, we see a lot of her innovations.”

Having been given vast amounts of information, Durald Arkapaw put it in front of the camera to test it and make sure the colours were appropriate. Areas examined included what colour the sun should be in line with the Mayan culture, and what colour the water should be in the depths of the ocean and outside of that in Wakanda.

The colour of the light was also important to determine early and guaranteeing this was maintained all the way through the VFX pipeline. “Also in the grade, we needed to use the same LUT, so there were no huge surprises,” says Durald Arkapaw who wants the director to see close to the final image on set for scenes that are in camera. “But we didn’t want to change all the colours of Wakanda – it’s something special which we built off. When you use a new camera, or you’re introducing a new colour science, it’s about making sure everyone likes that colour. Even though the shades may be different to the first film, we needed to make sure this lens and camera stay true to what the colours represent.”

Having worked with gaffer Brian Bartolini for almost a decade on multiple projects, Durald Arkapaw has developed a shorthand with him. She sent him references including beautiful illustrations from Beachler and underwater images to examine when discussing where the source of light would come from and starting to build the look. “Brian is a talented gaffer, and we share the same taste in lighting, he also runs an amazing crew. The images I sent him aligned with the ideas Ryan wanted to develop which included a deep space vibe for the underwater world where you’re not sure what you’re seeing and can’t make out far in the distance.

“I’m so in tune with light, from the way I like it to fall in a room through to the combination of hard and soft light. Brian and I have the same sensibilities and taste – we tend to like a lot of soft overhead light as our base, but we bring in other sources. I like a mix of hard and soft sources. When you have a great crew supporting you, and they’re amazing in prep, rigging and thinking ahead, you can also make changes on the fly that don’t affect production, director, or actors.”

Preferring not to light on the floor – “as you don’t want actors walking on set and seeing a bunch of lights on the ground and having to move through them” – soft boxes with different diffusion were often used from above. “For our big Boston night exterior set we used two 40×40 soft boxes with 64 S60 SkyPanels rigged with movers, in addition to some S360s in scissor lifts for our ground package, allowing us to work with units that could move and be turned on and off to create the desired contrast as we shot different directions.

“It was important not to affect production by bringing in big rigs that take a long time to adjust or move on the shoot day. We like to build it into our rigging plans, and then tweak and shape it on set. One of my favourite sets is Jabari Land Council in M’Baku’s lair where he’s sitting in a beautiful chair with all the tribes around him and snow is falling. We used a really hard source that bounces into the snow and skip bounces onto the character which is something we liked to play with. I also love Hannah’s work in that set and the burnt wood that creates a beautiful contrast. When combined with Tom’s LUT, the skin tones are very dense and have so much life.”

The cinematographer was also delighted to have “genius fixtures foreman” Phillip Abeyta on board, creating a variety of bespoke fixtures. As Durald Arkapaw likes to use sodium vapour units for night exterior work, Bartolini and rigging gaffer Adam Harrison introduced her to the Fiilex Matrix Color 320W LED Fresnel Punch Light, which was used for the night exterior work in the cargo ship sequence and at Riri’s garage night exterior in Boston.

“We also used a lot of Creamsource Vortexes in our bigger blue screen stage rigs, which were amazing because they’re very punchy,” she adds. “Brian and lighting control programmer Scott Barnes could pixel map them. We used them as a punchier backlit sun source or sometimes we used it for our fire effects work.”

Thriving on collaboration

Although virtual production was not used extensively, some car work pickups in Boston were shot over a few days using the technique. “It takes a lot of preparation shooting the plates and getting all departments on the same page,” she says. “We like to do as much as we can in camera, so the images look their best. Giving the VFX team at Weta as much as you can in camera is also essential because even if there’s VFX extension, you still want to give them something to ground it. Give them foreground, and middle ground, so they have something to hold onto.”

One of the most thrilling sequences to capture was a slo-mo scene which sees a bomb roll under a car and explode, flipping the car onto the bridge and throwing Shuri from her motorbike. “Ryan likes to direct the stunts as closely as possible which is fun for me because I get to be there every step of the way too. It’s so exciting when you can use a Phantom camera on a big set to film an action scene which features huge SFX elements,” says Durald Arkapaw.

“That car flip shot was filmed high speed at 312 fps, and we were working with a big night exterior set which required Hannah and her team to build a portion of the Boston bridge on our backlot set in Atlanta that then needed to be rigged. This meant we needed asphalt, rail guards, and lighting fixtures that matched those you’d find on the bridge in Boston which was around 500 feet long.”

The second unit in Boston including second unit DP Carlos De Carvalho shot pickups in camera on the Cambridge streets near MIT. The bridge fight that then occurs between Okoye and Attuma (Alex Livinalli) was also shot outside, on the same set the car crash sequence was captured.

Lessons learnt whilst shooting action sequences on Loki which were valuable when lensing Wakanda Forever. Durald Arkapaw likes to approach action scenes simply, breaking them down into steps: “If your main actor cannot do all the stunts and you need the stunt person to do the more complex stunts, but you can’t show their face, you’re not going to want to do face replacement for hundreds of shots. Therefore, you need to break it down by the numbers and figure out what’s needed for the sequence, and then approach it simply with the camera, whether it’s crane work or handheld.”

Adopting this approach, the cinematographer worked closely with the camera operator. “You make sure they know where cameras are going to be and that everyone is on the same page, so nobody gets hurt,” she says. “Shooting stunts can be tedious and there are a lot of people involved, which in turn means things go slower. Our stunts are thoughtful in their approach because Ryan is particular about how he wants to cover them and what he wants for his edit. There were also so many complex costumes and head pieces to take into consideration which took a lot more time too.”

The cinematographer felt “lucky to work with thoughtful and talented VFX supervisor” Geoffrey Baumann on such scenes who wanted the photography to stay consistent throughout and checked in with her frequently to guarantee this. In post, she worked with the visual effects team every day in the DI process, providing as many notes as possible.

“You want that through line to stay constant with the lensing in the VFX extension. This required a lot more mapping and charts than usual by VFX,” she says. “When you’re working with computer graphics and lighting in 3D, you must give notes to make sure elements such as the sun direction stay consistent with your on-set plates. I shared notes on how I like to frame, my preferred contrast ratio, and how I light on set. The VFX team did a beautiful job of making sequences such as those on the Boston bridge at night look like real extension in combination with our final grade.”

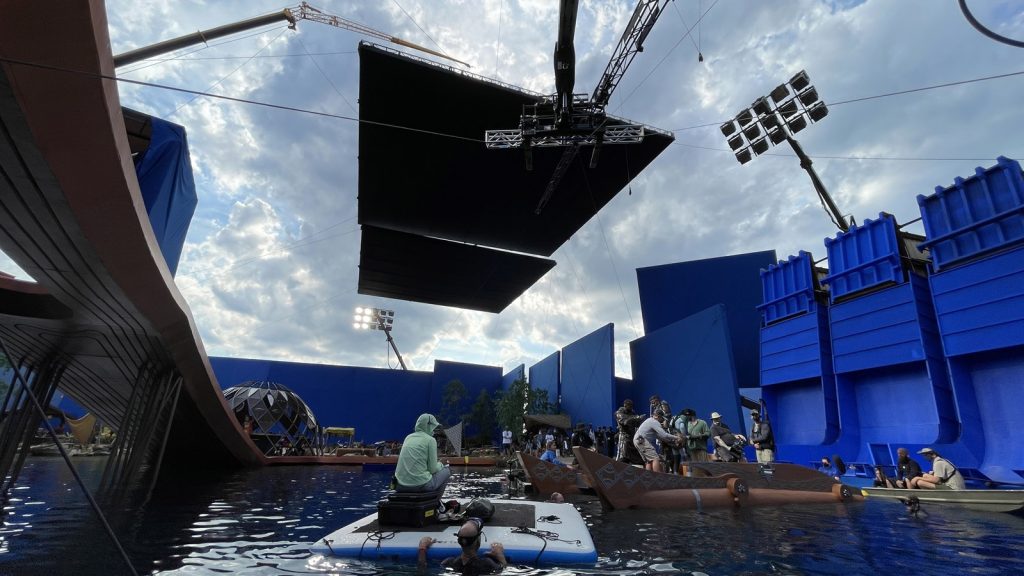

Creating the underwater kingdom of Talokan was demanding, realised through a team effort and boundary-pushing techniques. According to Beachler, Talokan took nearly two years to develop. “We started at the very beginning,” she says. “Where are they located? How did they get there? How did they survive?’ We wanted the underwater city to be modern but with the architecture they would have taken with them. It’s mysterious and provocative and gorgeous.

“It’s a big city. It was built largely in VFX, but we built Namor’s throne room, which is fabulous, bright red—that is the colour of Talokan. I think it works really well under the water. When you’re in his throne room, you can see hieroglyphs that surround the back.”

Beachler felt the underwater city should be built mostly with stone, and couched it in Mayan-inspired architecture, colours and iconography that is a homage to a civilisation that is still very present but also has a classic feel to it. “It felt like starting over just like when I walked into Wakanda,” says Beachler, who developed a 400-page guide for the undersea kingdom.

A signature colour of Talokan, red features throughout the film in key areas. But placing it underwater proved challenging. “We’re breaking some barriers with colour because red is very hard to see in certain depths of water,” says Durald Arkapaw. “But red is an important colour and we made sure it pops in water. VFX post supervisor Geoffrey Baumann, Hannah and I worked together, making sure everyone was getting what they wanted in colour and seeing things at certain depths. And Ruth [Carter] has such beautiful costumes that you want to make sure that those colours pop and that they flow the right way. With this challenge came a lot of creativity because it is a new world.”

Capturing the underwater shots called for a strategic approach, using the same 2x anamorphic lenses as were selected for the rest of the film. Intricate planning was demanded for a scene which sees villain Namor descend into his underwater throne when Nakia tries to save Shuri and one of the Talokanils is killed. Pre vis and Unreal Engine were integral to visualise how light would fall and the texture it would have underwater.

“We shot it wet for wet and also dry for wet. Hannah made his Megalodon thrown which we had on a stage and instead of using blue screen, we printed the circular texture of his throne room onto material so the light would bounce off the surface and produce the right colour quality,” says Durald Arkapaw.

“So, we filmed him descending on wires into his throne in water, as well as in a dry environment so we could see how his headpiece, mouth, body and costume moved, lighting them the same in both scenarios. When we shot it underwater it was rewarding to see the end result after elements such as the wires and the straps to keep his headpiece in place were removed by Weta who did all our underwater VFX work and were brilliant.”

The crew also flooded large sets for sequences such as one featuring the North Triangle. Bringing such scenes to life required 40 feet high water tanks to flood the street “that would fill your average swimming pool in two seconds, and led by Dan Sudick, one of the most talented SFX supervisors with extensive experience,” says Durald Arkapaw. “I always work closely with SFX, for example, because it’s so rewarding for me to capture scenes in camera, even if things might be altered in post.

“While some say they don’t enjoy the big budget stuff, I really do. I like working with multiple teams and helping the director tell a story that’s big and broad, but also making it feel intimate and using effects to make it look real. That takes skill from all departments, and I thrive on that collaboration.”