SOARING ONTO THE SCREEN

More than three decades after Top Gun became a high-flying force of filmmaking, aviator Pete “Maverick” Mitchell returns to the screen for more airborne thrills in Top Gun: Maverick. Cinematographer Claudio Miranda ASC and the talented team of aerial specialists reveal how air-to-air and ground-to-air techniques along with in-cockpit cameras captured the speed of the aircraft and immersed audiences in the supersonic action.

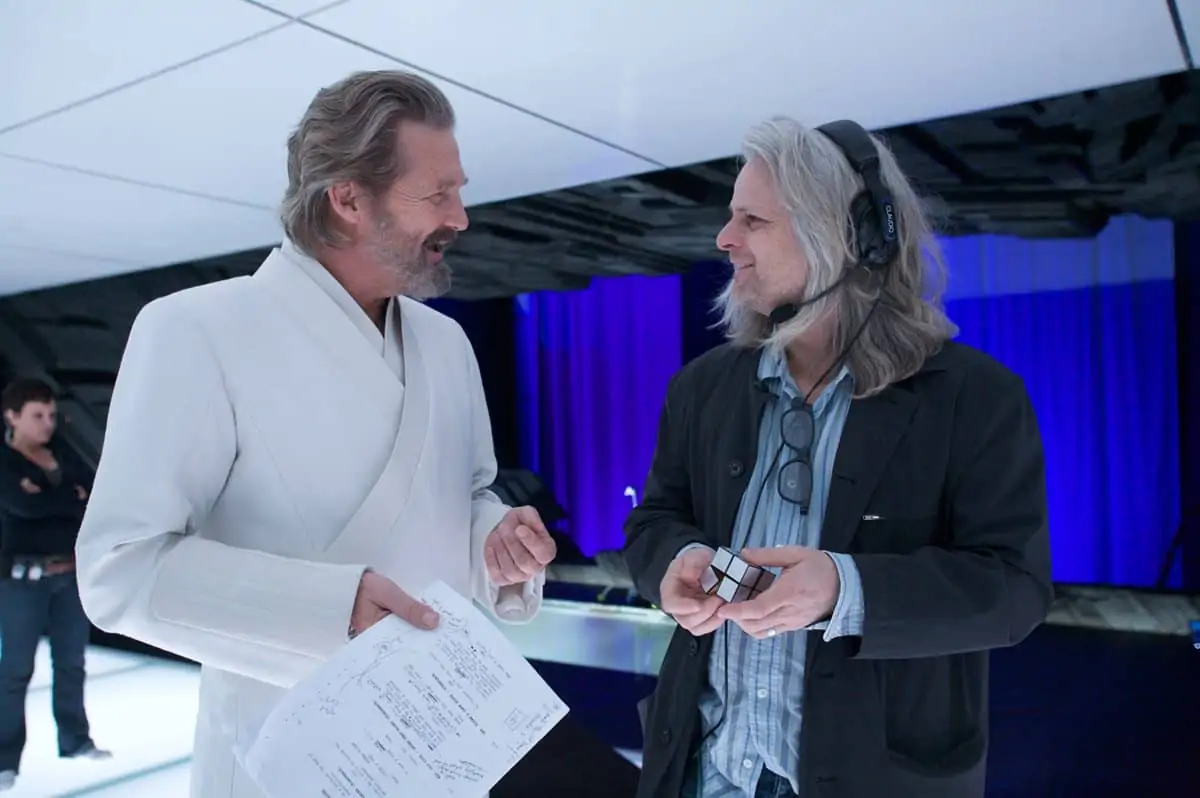

The filmmaking values and ambitions of cinematographer Claudio Miranda ASC and director Joseph Kosinski have aligned throughout their collaborations. On their latest production, Top Gun: Maverick, they were once again in complete agreement that “nothing beats reality.”

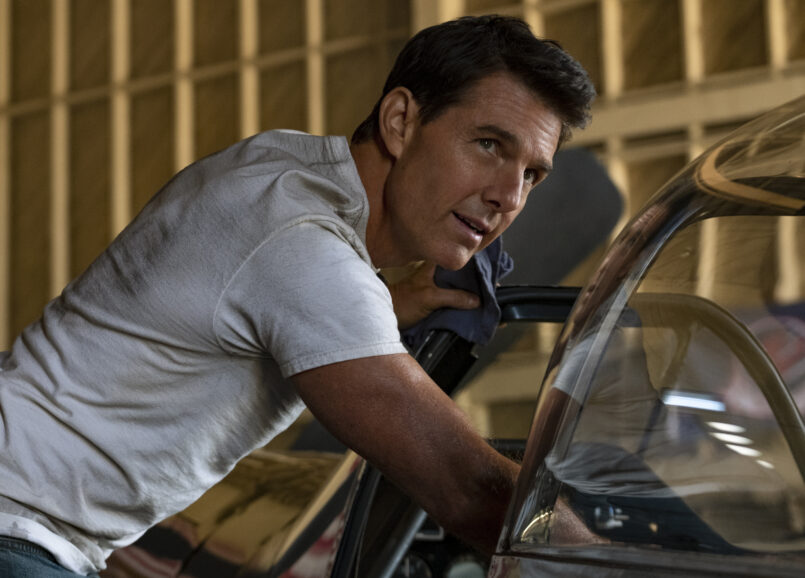

Having united on movies including the artistically bold and technically adventurous Oblivion (2013) and TRON: Legacy (2010) through to the more grounded firefighter action-drama Only the Brave (2017), their sixth collaboration sees the pair achieve a visually spectacular and immersive cinematic experience as Navy aviator Pete “Maverick” Mitchell (Tom Cruise) returns for more fast-paced and daring aerial missions.

“Joe and I like to do things in camera as much as possible while always striving to do something different from our previous movies,” says Miranda. “We hated the idea of putting pilots against a blue screen or shooting in an LED volume.”

To keep visual effects to a minimum the filmmakers – working closely with Cruise and a tenacious crew – investigated how to place multiple cameras inside and around the aircraft cockpit to capture the actors as they soared through the air in addition to the other air-to-air and ground-to-air aerial photography. Miranda knew he must start early to receive Navy approval for the plans to capture the footage, a process which included investigating aircraft modifications that might be needed and discussing safety regulations with the Naval Air Systems Command.

Starting planning three to four months prior to principal photography, Miranda modelled a mock-up of a Cinejet – an Aero L–39 Albatros jet featuring a customised gyro-stabilised Shotover F1 Rush camera platform designed for high-speed aerial cinematography – and visited the naval bases to demonstrate to the Navy where he and the team planned to position the cameras.

Although initially met with the response, “You’ll never get six cameras in there,” the cinematographer was undeterred. Continuing his aircraft research, Miranda discovered an older model of the F-18 fighter jet which he thought could offer the perfect platform for the cameras.

“I asked the Navy what each instrument was for and then, working with 1st AC Dan Ming and key grip Trevor Fulks, we stripped out anything that wasn’t required until there was enough room for six cameras,” he says. “That was only possible because we had early access. It was also beneficial everyone in that group at the Navy loved the original Top Gun. It was the reason some of them joined the Navy, so there was tremendous support there.”

A eureka moment

Prior to becoming an award-winning cinematographer, Miranda was a gaffer on three movies directed by the late Tony Scott, who was also at the helm for the original 1986 Top Gun. “I knew nostalgia would be an important part of creating this movie,” says Miranda. “Tony was always one for sunset grads with that orangey top. We honoured that in a couple of shots, so it felt connected to the first film.”

While not wanting to “copy the original”, partly because they could not capture shots of Cruise in the air when shooting Top Gun, Miranda took cues for colour and some longer lens choices. “Tony also loved blinds and slats, so there’s a reference to that in the scene where Rear Admiral Chester “Hammer” Cain (Ed Harris) is in his office,” says Miranda.

Filming took place almost entirely in real locations with long periods spent on aircraft hangars to establish real photography. Like the original, much of the movie was filmed at the Naval Air Station military base in Lemoore, California. “San Diego was also a big location in the first film, so we shot at the naval bases and hangars there, filmed the classic motorcycle chasing the F-18 sequence, and built the bar at the beach on the base,” says Miranda.

Many of the flight scenes over land were captured from the ground at NAS Fallon, Nevada. Other locations included in and around Lake Tahoe and the Washington State Cascade Mountains, where the final fight scenes were filmed, the USS Abraham Lincoln, where flight deck operations scenes were captured, NAS Whidbey Island, and USS Theodore Roosevelt.

Working with production designer Jeremy Hindle was a “wonderful experience” for Miranda and they talked extensively about how he would dress each real location, when required. They then went on to shoot another film with Kosinski, Spiderhead, which was a “completely different animal and required huge set builds.”

Two weeks prior to principal photography, Miranda was asked to shoot elements for the montage sequence on the aircraft carrier such as jets taking off, taxiing, and landing, working with a small crew and no directors. When planning how to capture the sequences initially he struggled to achieve the right light. But then he experienced a eureka moment.

“The way the ship, which the aircraft were on, was positioned wasn’t allowing me to achieve the desired light,” he says. “Feeling dejected as I walked down the hallway, someone asked me how the shoot was going. I explained the lighting problems I was encountering, and they replied, ‘Son, we have 23 years’ worth of fuel on here, and we can turn wherever you want.’”

At four o’clock the following day, the boat turned to the exact position Miranda had requested. “It was so amazing, I almost cried with joy,” he says. “I later discovered the person I had talked to was one below the captain; he was one of the best gaffers I’ve worked with. From then on, each day I was assigned someone to turn the boat to the desired position.”

Having been a gaffer, Miranda admits he can find it “tricky to let go” when working with other gaffers. “I like to plan and plot everything,” he says. “On previous productions, I had an excellent gaffer I loved working with – Erik Messerschmidt. I thought, it’s not going to be long before he’s a star. And then he went off and became an Oscar-winning cinematographer.”

On this occasion, Miranda worked with chief lighting technician Andrew Korner to achieve his lighting ambitions.

Miranda’s philosophy is “to light as naturally as possible. It’s all about the eyes and how we connect with them. Especially in a close-up, the eyes reflect the natural environment around them – real reflections versus a square or rectangle that’s synthetic.” He also considers skin another precious reflective medium and finds “the world and natural environment does an amazing job of lighting people in a way that makes a film feel grounded.”

That is one reason he delights in shooting in real locations. “It’s what makes me want to make a movie. Being surrounded by green screen or an LED volume for two months does not appeal to me in any way.”

If a scene looks unrealistic, Miranda instantly spots how to adjust the lighting to rectify the problem. When shooting the scene in Rear Admiral Cain’s office, initially an ARRIMAX on a Condor was placed 300 feet away to create the effect of sunlight shining through windows of the set. “But that just didn’t look far away enough because that’s nothing compared to the distance of the real sun. So, we often moved the light even further away to make it more believable.”

His process of planning and visualising scenes and how they will be lit has also been transformed by using Cinema4D modelling software and OctaneRender render engine – an innovation Miranda plans to include as part of his lighting toolkit moving forward.

“I’m really into pre vis and do my own modelling of scenes,” he says. “It helps me define borders, decide if I want walls removed, and work with the production designer on colour. I’ll set up my own lighting schemes, run simulations, and then share them with the gaffer.”

This method was used to visualise the set-up needed to create the red lighting featuring in a scene in as Maverick walks down a hallway before boarding the hypersonic Darkstar. “It had to be really a neat and tidy rig because all the lights are in shot,” says Miranda. “That lighting effect was achieved using the new Kino Flo four-foot RGB FreeStyle T41.”

Restricted spaces

When determining the best approach for Maverick, discussions with Top Gun cinematographer Jeffrey Kimball ASC about challenges he faced when lensing the 1986 movie, such as those relating to aircraft and heat, were invaluable. These highlighted that the set-up would need to be small, light, and offer close focus, and confirmed shooting spherical was most suitable.

Kimball stressed Miranda would have to be mindful of weight because a small item weighing 5lbs could weigh more than 40lbs when flying at 7Gs. “Shooting anamorphic would be heavier due to the added complexity and larger glass elements,” says Miranda. “And as we also couldn’t operate the cameras once they were locked in the cockpit, I thought shooting spherical might give us more latitude if the actors moved up or down due to G-force.”

The confines of the cockpit sometimes meant the whole system had to fit in the space of a few inches alongside the actors. Having already helped Sony with the development of the Venice camera, Miranda also played a vital role in informing the development of the Rialto, the extension system which was instrumental in the success of the aerial scenes captured from the cockpit and allows the Venice’s front image block to be removed and mounted in smaller housing.

“We wanted to shoot full frame as much as possible, so I asked Sony if they could figure out a smaller solution, because the Venice was too big to fit in the cockpit with the recorder,” says Miranda. “They came up with the genius idea of remoting the sensor.”

The concept evolved into the Rialto as it is today, allowing Miranda to mount cameras all over the cockpit and making Top Gun: Maverick one of the first films to use the Venice and Rialto. Miranda originally planned to implement this in the sequences shot by aerial DPs in the Cinejet too but decided to use a smaller lens package.

“When using the Rialto’s E-mount option, the camera package, including the lens, was about two-and-a-half inches long in the cockpit. That was super critical because no lens could go beyond the ejection seat pathway,” says Miranda. “Rialto also made it easier to mount a camera on the front of a motorcycle which Tom loved because it wasn’t a big beast on the front of the bike making it wobbly or unsafe.”

The cinematographer has the same aim for his next production exploring the world of Formula One racing. He’s been “figuring out what kind of camera systems to use on the cars to achieve everything in camera, and to feel the speed with the actors. That’s key as the audience knows, even with the best CG, what’s real.”

Renowned for his ambitious and daring performances and dedication to his productions, Cruise drew on his passion for and knowledge of flying to take to the skies in a jet with a pilot performing the aerial stunts, complete with huge G-force. Rather than being filmed in front of green screen or in an LED volume, the other actors also braved the G-force with Cruise in the jets.

The actors flicked a switch on a system built by the crew to turn on and off all six cameras in the cockpit. Working with Keslow Camera, the crew also designed and implemented a device which displayed the status of all the cameras. Nothing could be attached to the airship’s power system, meaning lithium batteries offering 90 minutes of flight time were required.

“I also worked with a fantastic key grip, Trevor Fulks, who sadly passed away from cancer during the production,” says Miranda. “He oversaw all rigging around the jets and was outstanding. Trevor worked with the Navy, heading up the planning, mounting of equipment, safety considerations, and calculating weight load.”

The ability to change the Venice’s internal ND was critical in saving time on the occasions when Miranda had to guess exposures for aerial sequences captured in the cockpit, “looking where the jets were flying, what the weather would be like, assessing the canyon they would fly through, and locking in exposure.”

Knowing the RAW recorder could not fit inside the cockpit, footage shot inside that space was captured 4K to SxS cards at full frame, compared to the rest of the film’s 6K sequences. At first Miranda was a “little nervous about not having the full bit depth RAW recording, but to get all the cameras in there, that was the only option.”

The only other camera small enough was the GoPro but he “wanted something more cinematic, and to be able to control the camera, shutter, and NDs. Now the Venice 2 has been released, we wouldn’t have any issues, because it’s smaller and the recorder is built in.”

A bold and multi-faceted production such as Maverick also demanded an extensive lens selection to suit. ARRI/Zeiss Master Primes – 50mm and upwards – were used to cover full frame, with Sigma FF High Speeds covering everything below that in the prime world. Elsewhere, the Fujinon Premista was used, and the interior of the planes was filmed using 21mm, 25mm, 35mm, and 50mm 6K full-frame Zeiss Loxia E-mount lenses.

“The lens list is ridiculously long,” says Miranda. “To go even further beyond that wide angle, we used the small and robust 10mm, 12mm, and 15mm Voigtländers. And in full frame, that’s pretty wide. The centre top camera in the aircraft was paired with a 10mm Voigtländer.”

For the ground to air shots, they wanted to use long lenses, and chose the 75mm-400mm Fujinon Premier with doublers and converted Canon 150mm-600mm still lenses also with doublers. In the jet’s Shotover F1J systems they also used Super 35 Fujinon Cabrios – a 20mm-120mm and an 85mm-300mm – and a 25mm-300mm Cabrio in the helicopter. Fujinon zooms were also used for most of the ground-to-air and air-to-air footage.

Flying force

From the sequences inside the cockpit with the actors through to the air-to-air and ground-to-air shots, the ways in which the multiple forms of aerial sequence were as ambitious and wide ranging as the aerial stunts.

“Smooth motion does not always create the feeling of speed on screen; it’s sometimes produced through misframing, for example,” highlights Miranda. “And when a jet is moving at speed and shooting another jet, it doesn’t always make it feel like it’s very fast. Therefore, shooting from a helicopter was also a great solution.”

The cinematographer avoided film references because they “had been done before”. Instead, inspiration for some of the aerial shots came from a rather unusual source – Paths of Hate – an “obscure and rather dark animation includes an incredible aerial sequence.”

“Top Gun wants to stand alone as being different,” he says. “So, I thought, why not go to where people can fly and move the camera more freely? In animation, you can do anything you want, so let’s make that the goal and come down from there.”

Outside of the action captured in the cockpits with the actors, a team of talented aerial specialists were instrumental in the sky-high success of the soaring shots. Miranda brought friend Kevin LaRosa II (Iron Man, The Avengers, Transformers 5) on board, a third-generation pilot and second-generation aerial coordinator and stunt pilot who had already discussed Maverick with Cruise when they collaborated on previous projects.

“Tom always emphasised how important it was for the aerial sequences to be real,” says LaRosa. “I knew the jet-based platforms we had back then in around 2012 were antiquated, so I set to work trying to figure out how to set the bar higher and develop next level systems to help tell this incredible story.”

As LaRosa’s design went through multiple iterations he experimented with which jets and camera gimbals were most effective. In 2017, he created a design of an L-39 Albatros with a highly manoeuvrable Shotover gimbal on the front. This later became the Cinejet. LaRosa worked with Patriots Jets – a civilian-run jet aerobatic team with a fleet of L-39 aircraft – teaming up with Randy Howell, Patriot Jets team owner, to modify the jet with cabling and bracketry that could hold the Venice camera.

“It was specifically made for Top Gun: Maverick and Shotover modified the F1 Rush so it could fly 350 knots and 3Gs,” says LaRosa. “It was my dream to have an aerial DP sit behind me while I flew the jet, so we could get in the dogfight aerial battle, fly through the canyons, right next to the afterburners, and capture the action using the latest and greatest technology.”

The moment LaRosa discovered the dream would become a reality will live long in his memory. “An executive producer on the movie called me and said, ‘We know you built the Cinejet and that you’re an incredible jet pilot. We want you to do the jet work on Top Gun: Maverick.’ I remember keeping my cool and then when the call ended, I yelled at the top of my lungs because it was one of those incredible moments in life.”

Prior to principal photography, aerial camera tests continued, testing a variety of lens combinations and camera moves in the different aircraft. “Claudio and his team were right there every step of the way, critiquing and giving notes,” says LaRosa. “Claudio didn’t rest until he had the perfect product. The Cinejet gave him the ability to fly his preferred camera package, which wouldn’t have been possible with the technology that existed before.”

As well as helping achieve the epic exterior aerial shots – flying either the Cinejet, Phenom 300 jet, or helicopter equipped with camera gimbals, and joined by aerial cinematographer, David B. Nowell ASC – LaRosa’s role as aerial coordinator saw him work closely with the Navy. Collaborating with Navy technical adviser, Captain Brian Ferguson, LaRosa scheduled assets and crew and determined how to turn Kosinski’s “creative wishes into reality, in a safe and legal way, whilst pushing the limits of what had been done before in aerial cinematography.”

Aerial cinematographer David B. Nowell ASC – who had worked with Tony Scott on the original Top Gun and collaborated with Miranda and Kosinski on Oblivion and Only the Brave – once again captured scenes of aerial magnificence for Top Gun: Maverick, scouting the most suitable locations with LaRosa and then working alongside fellow aerial cinematographer Michael FitzMaurice in the aircraft LaRosa flew.

In prep, Nowell and FitzMaurice decided what the aerial scenarios should be and how they would be achieved. FitzMaurice was “honoured to help create such an iconic movie” and work with the aerial DP who captured the first Top Gun, referring to Nowell as “the godfather of aerial cinematography.”

“When I was asked to come on board to work alongside him, I jumped at the chance. How could I not want to work on this?” he says. “David, Kevin, and I cringe when we see CG aircraft in films. They never get the physics right; it just doesn’t look real aircraft. It was fantastic everybody involved in this production wanted to use real aircraft.

Before shooting commenced, Nowell, LaRosa, and FitzMaurice filmed small model F-18 jets on sticks on their iPhones and used the edited sequences to outline their plans to Cruise and Kosinski. “Editor, Eddie Hamilton, really liked it, and used some of it as the rest of the film was being shot, plugging it in to roughly envisage how the aerials might sit within the film,” says Nowell.

LaRosa, Nowell, and FitzMaurice also created “an aerial menu book” of moves and angles that had not previously been captured in films. “We wanted to create the most dynamic, energetic aerials ever seen,” says LaRosa. “To do that you had to test extensively to see what works and what doesn’t.”

After deciding which platform was best to shoot each type of sequence, the aerial team broke it down into what should be filmed in the morning and evening, working around the Navy pilots’ schedules. To capture the best quality of light, Miranda wanted the two daily runs to be East or West facing as much as possible, shooting towards the East in the morning, and the West at sunset.

“That informed how we mapped everything and how deep in the canyon we could go,” he says. “One really low aerial shot in the desert, below 100 feet, almost looks synthetic and like a CG shot, but that’s completely real. Maybe because we just don’t see planes flying that low, it seemed like an unreal situation.”

In the original Top Gun, almost every scene involving aircraft was captured in a studio, with the actors in a mock-up cockpit against rear projection. “But the difference is striking in the few shots where the camera was in the backseat of the F-14, aimed at the pilot and capturing their reaction,” says Nowell. “Tom, Joe, and Claudio wanted to achieve that kind of look, so they proceeded down that road of how to get the cameras in the cockpit which also encompassed Tom’s idea to have all the actors in there too, going through the training to be able to withstand all these Gs.”

However, as 75% of the original Top Gun was captured from a mountain top using long lenses, Nowell emphasised that type of photography would also be essential in making Maverick a success. “All the other footage from mounted cameras on the jet and in the cockpit was great but to get outside and capture the speed the jets can travel through the canyons, you need a long lens look,” says Nowell.

This saw Nowell and three camera operators spend a week on top of the mountain, shooting from four camera positions, while FitzMaurice captured footage from the helicopter and LaRosa’s father Kevin LaRosa Sr. – who LaRosa refers to as “his idol and an amazing aviator with a wealth of knowledge” – was on the ground helping coordinate the capture of air-to-air and ground-to-air footage.

For the editing to work and to push the energy, FitzMaurice believes “having the different angles is essential. If you just go up with the jet and track with them together, it can appear too slow.”

Nowell also shot a ground-to-air scene of the jet flying by the tower at NAS Fallon near where he had captured a similar scene with Tony Scott for the original Top Gun. “Filming at the same location I had been with Tony 34 years prior was a nostalgic and very special experience,” he says.

Expanding the horizons

Once Cruise and Kosinski began working with the actors and pilots, the planned movement of the jets allowed LaRosa, FitzMaurice, and Nowell to decide which shots were best covered from the air by a jet or helicopter or from the ground.

The Cinejets were the first aircraft to be brought into the aerial mix. “As we had to keep the camera and recorder package together this limited the lenses we could use, eventually working with the Fujinon Cabrio 20-120mm and 85-300mm,” says Nowell.

The first aerial sequences Nowell captured in the backseat of one of the Cinejets flown pilot LaRosa were of Cruise’s canyon runs. The L-39 was suitable due to its small size and ability to fly at the same low height as the F-18s. “But we were limited by the fuel we’d have to fly quite a distance, so we would do a couple of runs and then return to base.”

Later, as they captured scenes in the Cascades Mountains, the Phenom 300 was used because it offers two cameras, three hours of fuel on board, and both Nowell and FitzMaurice could be on board with LaRosa, shooting different coverage simultaneously.

“In that scenario, I was always in the back of the cabin looking forward, using the camera mounted on the nose and a 20-200mm lens, but I could also turn around to look back,” says Nowell. “Michael’s responsibility was shooting the more exciting footage using the longer 85-300mm lens, looking rearward at the front of the jets.”

Miranda had initially thought the 20mm-120mm would cover everything, but then found “sometimes the longer lenses made it more messed up and created a greater sense of speed.”

Although the aim was to push for as much speed as possible and the aircraft the actors were in reached 7Gs, the jets Nowell and FitzMaurice were capturing the action from were limited by the speed of the camera of 350 knots and 3Gs. “To make it look a little faster without becoming too jerky, we dropped the frame rate down to 18 frames,” says Nowell.

“That camera system can go faster and handle more Gs than others though, so we were working with the best system for the production,” adds FitzMaurice. “We also had a whole support team behind us – the technicians for the Shotovers, the ground crews for all the aircraft. It’s quite a list and we couldn’t have done any of this without all of them.”

As well as starring as Pete “Maverick” Mitchell, Cruise was one of the film’s producers and encouraged the crew and cast to go further, if possible. “He also helped ensure the pilots had the resources and time to film more aerials,” says Miranda. “In the end, around 500 hours of aerial footage was captured.”

LaRosa finds Cruise to be a “consummate professional and a true entertainer” and was impressed by his passion for coaching and assisting others around him so they can have the same drive to create the best production possible.

“Early in filming, Tom gave a speech to the cast and crew and said, ‘Guys, we are at a disadvantage because we are making a sequel to a very iconic and historic movie. We had to wait 30 years for there to be a story worth being told and for the technology to help us tell that story. We have no choice but to shoot this movie with a level of cinematic perfection that’s never been obtained before.’” says LaRosa.

“It was that drive and setting that bar so high that gave us our motivation as a crew to stand with him and Joe to make this production. That’s why it’s doing so well – cinematically, the movie is beautiful, the story’s incredible, and every sequence is perfect, in my view.”

Kosinski’s talent for storytelling and eye for symmetry was also integral. “The creative direction he gave the aerial DPs and I allowed us to be an extension of him when we were in the air,” adds LaRosa. “He’s so good at translating his thoughts, debriefing us after watching footage, and sharing critique and ideas.”

Immersed in the action

Top Gun: Maverick was among the first releases certified as “Filmed in IMAX” as part a program launched in 2020. IMAX has also certified independent camera rental houses who can supply accredited cameras – including the Sony Venice – worldwide. One of the first rental houses announced was Keslow Camera, which supplied the camera package for Maverick.

IMAX will select a limited number of films to participate in the programme each year, implementing best practice guidelines for the production to take advantage of each camera’s highest possible capture qualities and settings to maximise the IMAX experience. This includes IMAX’s exclusive expanded aspect ratio, which delivers audiences at least 26% more image than standard theatres.

“We still wanted to honour the 2.35 anamorphic aspect ratio for the most part,” says Miranda. “So, most normal theatre viewing is 2.35, except when the film opens up to full screen 1.9 for the IMAX aerial sequences which make up almost an hour of the film. The aspect ratio we shot most of the film at is 17:9 to offer a little room for reframing.”

The cinematographer believes IMAX is a different viewing experience because it was built to immerse the audience in their surroundings. “You sit in the middle seat of an IMAX theatre, and you’re fully submerged in the frame, whereas when you visit other movie theatres, the screen is set back a little, and you see the physical frame. IMAX is a different animal, you’re just more involved in the movie.”

LaRosa commends Paramount, Cruise, Kosinski, and producer Jerry Bruckheimer for delaying the film’s release for two years to ensure audiences could watch it at the cinema. “Top Gun: Maverick is huge, epic, and stunning,” he says. “You absolutely need to watch this movie on the biggest screen with the loudest sound system possible. When an F-18 flies by, you feel the rumble in your chest, so to let the audience live this movie as if they were there, you also need the immersive sound of the cinema.”

Audiences can also enjoy a ScreenX version of the film, displayed in a panoramic format and projected on expanded dual-sided, 270-degree screens on the walls of a cinema. “For this, we used extra wide cameras to fill in left and right projectors, since we didn’t have cameras shooting those angles,” says Miranda.

Placing reality at the fore throughout allowed the team to capture aerial sequences to be proud of when viewed on the biggest screen possible. “There’s a difference between the carrier take offs in some other movies and Top Gun: Maverick,” says Miranda. “Most people know the pilot is thrown back and audiences understand that language. However, they don’t understand that when you take off from a carrier, you drop for a second. That’s what most movies are missing – that visceral drop and that’s what makes our film feel real and why we tried our hardest to keep it all in camera.”

Outside of the almost completely in camera production, visual effects required for elements such as aircraft explosions, were carried out by the team at Method Studios, headed up by Ryan Tudhope. Miranda also worked with Stefan Sonnenfeld, senior colourist, co-founder, and CEO of Company 3/Method Studios, to refine the look in the grade.

As Sonnenfeld was responsible for the 4K grade of the original Top Gun, he was well versed in the look that needed to be achieved to remain true to the original. “For Maverick, we added a grain in DaVinci Resolve to make it feel more filmic,” says Miranda. “That’s also why I didn’t go for shooting at 120 frames per second. Our minds enjoy being active on a creative level and love how 24 frames per second feels and to fill in the blanks. I feel like grain is also part of that abstraction.”

When Cruise saw the effects of adding grain, he agreed that the less sterile feeling suited the visual language of the production, as it had the film which preceded it. “We didn’t want this to be shot clinically, seeing every pore of someone’s face,” says Miranda. “It’s not that kind of examination. It’s an examination of a story point and the filmic grain gives you that feeling of those photochemical distortions similar to when you shoot on film. It just feels tangible, making your brain feels like it’s in a home environment.

“Some of the complaints about digital feeling cold or synthetic don’t apply here as this film is very warm, and it has distortions. We love imperfect framing and when jets are flying, and things are not centre frame. That’s what makes it real.”