A PERSONAL CONNECTION

Cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos BSC GSC and writer-director Kenneth Branagh reveal how their team created heartfelt coming-of-age tale Belfast, using an unobtrusive approach to filmmaking to craft an accessible experience infused with a love of cinema that captured the trials and tribulations of life in 1960s Northern Ireland.

An instant connection to the story was formed when cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos BSC GSC read the script for Belfast. This ability to relate to the compelling narrative has been shared by many others who have watched the semi-autobiographical coming-of-age film, written, and directed by Kenneth Branagh. It follows the experiences of nine-year-old Buddy – a fictional version of Branagh – and his working-class family during the advent of civil unrest and war in Northern Ireland in the late 1960s.

“My upbringing was quite similar. Cyprus was invaded in 1974 and we had to leave, so I lived in Dubai for much of my youth while my father worked in construction,” says Greek-Cypriot cinematographer Zambarloukos, who made seven films with Branagh prior to Belfast. “A traumatic event that changes your life was something I understood, so I felt a personal connection to the story. That’s the reaction many people have to the film; they tell me about something similar that happened to them.”

Believing it to be incredibly brave to reveal such a personal experience to the world, as Branagh did by sharing his story, Zambarloukos was eager to play a part in creating a smaller and more contained project than many of their previous technically ambitious, large-scale productions.

“Our first film together, Sleuth, was a small production with a very modest budget and schedule, and I enjoyed it so much,” says Zambarloukos. “We’ve been making quite grandiose films since, and never returned to the smaller and more personal ones. It’s something I’ve wanted to do for years with Ken. Personal projects are part confession, and they set you up as quite vulnerable. Ken’s script brought me to tears. I was so proud of him as a friend and of what he had accomplished.”

First and foremost, Branagh wanted the film to be an accessible cinematic experience that was not shot in a documentary style. It was also important that that film was infused with a love of cinema – which had played a big part since his childhood – whilst capturing the trials and tribulations of life.

“Belfast is a city of stories and in the late 1960s it went through an incredibly tumultuous period of its history, very dramatic, sometimes violent, that my family and I were caught up in. It’s taken me fifty years to find the right way to write about it, to find the tone I wanted,” says Branagh.

“I wanted to show the world through the eyes of the nine-year-old – movies, romance, religion – but then from the moment that world turns upside down, from when the ground is literally taken from beneath his feet, I wanted the film to reflect Buddy’s attempt to make sense of the chaos.”

Written in 2020 during the first lockdown of the pandemic, Belfast moved swiftly into production and was one of the first films to start shooting that summer. So that Zambarloukos could get a feel for the Belfast in which Branagh grew up, the director invited him and production designer Jim Clay to visit. They walked the streets and rented city bikes to explore the neighbourhood Branagh inhabited as a child, learning about the film and its characters as well as about each other during the process. “This opened up a new part of Ken’s world to me,” says Zambarloukos. “It took us back to the essence of filmmaking and the part of human nature that makes you want to exchange stories about your personal life.”

The decisive moment

A period of visual research followed in which Zambarloukos, Branagh, and Clay further investigated what Belfast was like during the period the film would be set. They looked at the work of Magnum photographers of the ‘60s including Welsh photographer and president of Magnum, Philip Jones Griffiths. “He took fantastic multi-layered photos of Belfast at that time – children playing while soldiers walk past, people shopping while snipers are on the roof of a supermarket, a woman mowing a lawn while a patrol passes through,” says Zambarloukos. “These helped us learn about that period and reinforced what Ken was describing.”

The filmmakers kept returning to black-and-white stills photography over documentary footage from the era. Henri Cartier-Bresson’s work was particularly valuable for its framing and the photographer’s reference to decisive moments. “That’s the essence of what a photograph is,” says Zambarloukos. “And this film is also about the decisive moment that changed Ken’s life.”

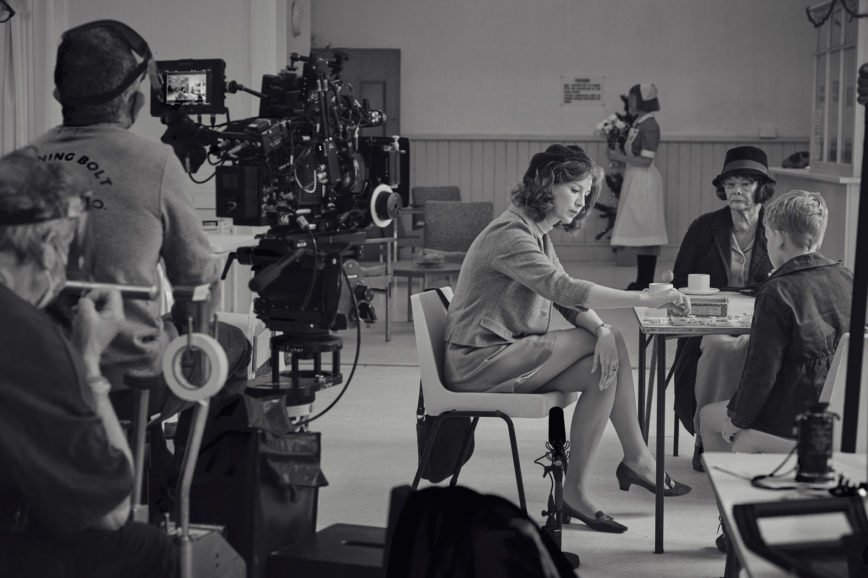

Dorothea Lange’s large-format portraiture, particularly her work focusing on people in trouble, helped evolve Belfast’s visual language and Zambarloukos was interested in the way she talked to her subjects and made them feel at ease. Whilst revisiting the work of such talented photographers who had mastered the monochrome still image, the director-cinematographer duo never considered shooting Belfast in colour. It was clear that black-and-white was the ideal choice for the heartfelt and personal story.

“Black-and-white is so lucid in its interpretation of human emotion,” says Zambarloukos. “It has this transcendental nature of being of the present and the past at the same time – it’s so truthful and emotive. By removing colour, elements such as shade of eye or hair colour aren’t so overpowering.”

Branagh made the decision to jump into beautiful Technicolour in a few select sequences such as when the family is immersed by the film they are watching – in contrast to Death on the Nile which is predominantly in colour with the first eight minutes in black-and-white. “This decision came out of a desire to first be descriptive about the real Belfast and then jump into the more fantastical to show the impact films had on Buddy’s life,” says Zambarloukos.

Branagh adds: “We were inspired by black-and-white photography. What I experienced as a child was also in a sort of monochrome palette because in Northern Ireland it rained a lot with little sunshine. For me, colour came from what was happening in my imagination. When we went to the movies, it felt like colour dragged your imagination into another place.

“I grew up with both colour and black-and-white movies, but there was what I later learnt to call a Hollywood black-and-white, a kind of velvety, silky, satiny black-and-white in which everybody seemed more glamorous. That’s what I wanted to use because a nine-year-old boy can see his parents as tremendously glamorous, and it also allows for everything to seem larger than life. I wanted that Hollywood black-and-white to be part of the mythology of this story, making even the most prosaic of environments feel glamorous or epic.”

Authentic and shootable

With the references explored and monochrome approach decided upon, Clay helped build a believable world. His accuracy when working with a variety of sizes of space whilst being conscious of how they need to be filmed has made working on Belfast and previous productions with the “master of his trade an absolute joy”, says Zambarloukos.

“He always finds the essence of something, the right kind of wallpaper, the right kind of texture. Over the years, we’ve worked on many composite sets with Jim – we built a composite 110-metre boat for Death on the Nile and a composite three-storey house for Artemis Fowl with integrated lighting. I believe our films have an authenticity without compromising shootability because of this. I don’t know anyone who is as good as Jim at that. He makes it easy. The dual nature of his craft means his creations are both authentic and completely shootable.”

Most of the film was shot on built sets in England and Northern Ireland with some city-based scenes captured in Belfast. Other locations used in and around London included a disused school site, a hospital, and a church. One of the most demanding built environments was the exterior street which was constructed at Farnborough Airport.

“We did some shooting in Belfast but because of the pandemic, it wasn’t feasible to take over a real street and ask people to move out of their homes,” says Clay. “It seems crazy that we built our set at the end of a runway at a small international airport where planes were still flying, but it worked out fine.”

A facade of houses was built which had to be shot for four different streets, so the challenge was to never shoot it the same way twice. “This was helped by the fact we shot very little coverage so rarely repeated ourselves,” says Zambarloukos. “We were quite laconic in that way, making it easy to choose angles specifically for scenes. You can’t call Belfast a studio film or a location film. It’s the result of the things we’ve learned through making composite sets with Jim on the more elaborate films, and then taking elements of that and scaling it to a very modest budget, schedule, and resources.”

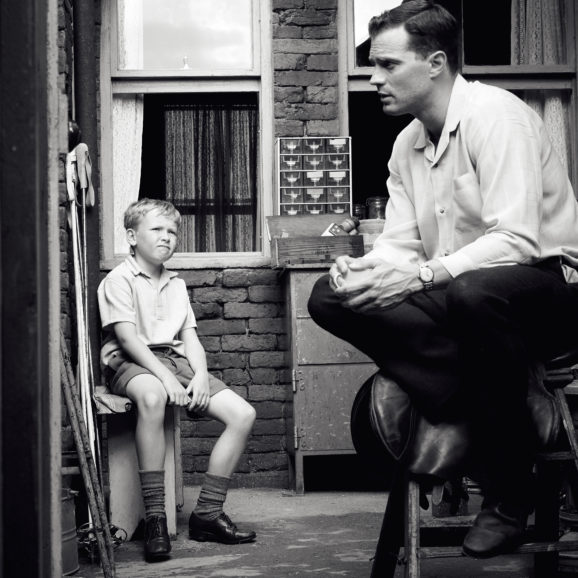

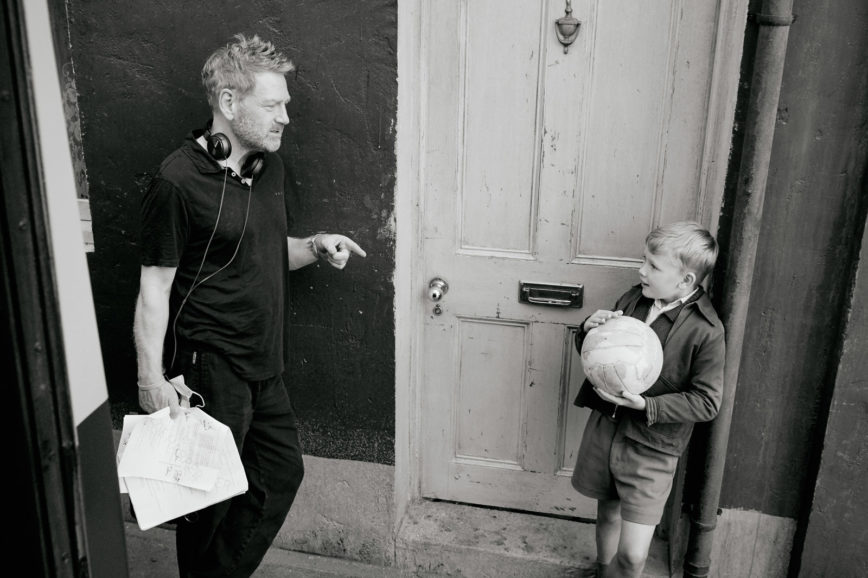

Concerned about the impact COVID could have on the production, the decision was made to shoot digital due to the immediacy it offered. Going down this route was also motivated by the fact the crew were working with a child non-actor – Jude Hill – as the lead. Hill had impressed Branagh in auditions as being “so natural in front of the camera that it was sometimes hard to believe this is his first film”. This meant a different method of rehearsing was adopted, some parts were improvised, and long takes were sometimes captured while the crew pretended not to be shooting.

“The first time I shot digital was on Locke in 2013 when I needed to film 30-minute takes. From that experience, I remembered what I would likely face when shooting this, making digital an easy choice,” says Zambarloukos.

For the cinematographer, the advent of the sensor size offered by cameras such as the ARRI Alexa LF has been a ground breaker in digital cinematography. “I’ve always loved the colour palette of the Alexa but found the sensor to be too small for some productions I was shooting,” he says. “The minute that got bigger with the LF, I felt I could achieve the definition and clarity I needed, particularly when working with wide lenses. The Alexa LF had just the colour palette, punch, and acutance I needed for Belfast.”

Panavision supplied the camera, the Panavision System 65, and Sphero large format lenses which Zambarloukos enjoyed using to shoot previous 65mm projects due to their banding and clarity.

“I tested other lenses where the fall off was quite severe, and although it appealed to me for short bursts, for prolonged takes, it was distracting,” he says. “The System 65 had just enough banding, and bokeh beauty without being distracting. They were balanced, portrait-friendly lenses.”

On this occasion, the banding was tweaked for a 1.85:1 ratio opposed to 2.40:1, and to suit Zambarloukos’ framing of Belfast which featured a lot of headroom and eyes placed low in the frame.

Conceptually and physically, the cinematographer felt he had to stand back, be silent, and listen when shooting. “That sometimes led to some odd and unbalanced framing which could be considered a mistake – too much headroom, people not centrally framed,” he explains. “I didn’t want to pan or tilt, so knowing where the action would take place, I would frame for that. This meant it wasn’t always balanced but it felt less intrusive and seemed to tell the story more eloquently.”

Branagh applauds the poetic sensitivity Zambarloukos expressed throughout the story. “For instance, in the scene where Pops [Ciarán Hinds] is in hospital, Haris found the most extraordinary angles and would go outside to find reflections,” says the director. “There’s a beautiful frame, high above the bed, of the three men. The grandfather’s slippers are empty, and the reflection of the nurses can be seen in the window. The position of the nurses was all a product of Haris responding to the scene with imagination.”

Camera movement had an “almost lyrical and musical approach”. Like in a musical score, the film needed pauses followed by more energetic moments. “Each one had to be earned,” says Zambarloukos, “so, based on the script and the emotion of a scene, we would work out a way to be still which would then lead to something more kinetic.” For instance, the camera is still for the scene in which a central character dies, but this sequence is followed by a boost of music and energy and a more lyrical approach to capture the wake.

Due to COVID protocols and the reduced numbers of crew allowed on set, Zambarloukos operated. While greatly enjoying the process and viewing “every obstacle as an opportunity for discovery”, he missed “my usual system of working with operators – my collaborators and good friends”.

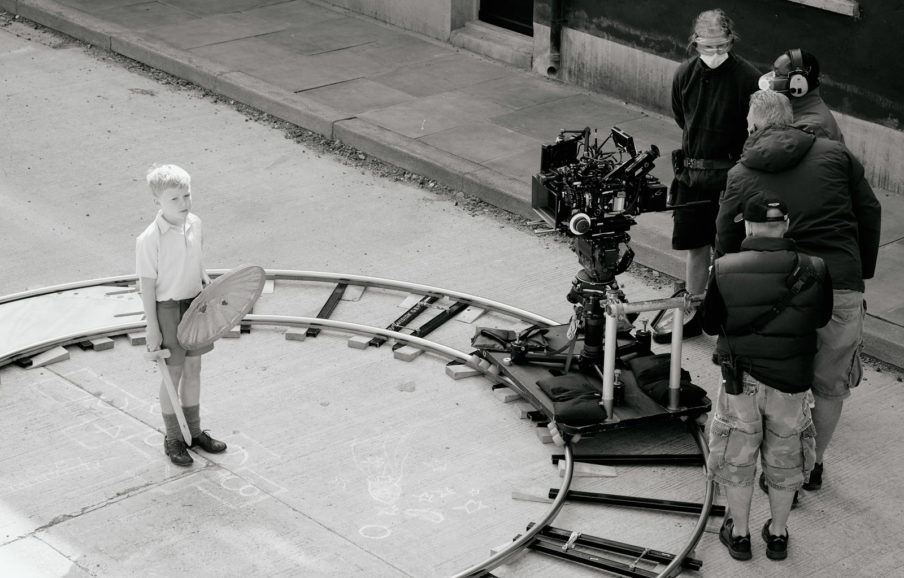

On this occasion, the cinematographer worked with his long-time collaborator 1st AC Dean Thompson GBCT; Dom Cheung – who is usually Zambarloukos’ 2nd AC and moved up to focus puller on many shots; 2nd ACs Mia Castles and Georgina Cook; 2nd unit DP Yinka Edward; and key grip Malcolm Huse. B camera and Steadicam operator Andrei Austin also operated the camera during a pivotal riot scene when a mob passes through the street and tears it apart. A circular track was used to centre the action around Buddy.

“Everything needed to revolve around him, and we didn’t want to lose sight of how his world was being turned upside down, so we decided to introduce a circular track,” says Zambarloukos. “While it was quite easy to centre the track around him, it was difficult to block the scene with so much key action in a continuous take, so everything coordinated around Buddy. Ken was so masterful in setting up and executing that scene.”

Projection specialist Lester Dunton – who Branagh and Zambarloukos had teamed up with on previous projects such as Murder on the Orient Express – offered valuable expertise in simulating vehicle movement in controlled settings. It was crucial when incorporating back projection into a scene which sees the characters returning from the theatre on a bus. Using poor man’s process, this was shot in the daytime on a stationary bus in a hangar at Farnborough Airport.

A magical realism

As with camera movement, an unobtrusive approach was implemented when lighting Belfast. People were placed near windows if they needed to be brighter or further back to appear darker. “We used the rooms and spaces to tell the story and allowed for fluctuations in weather and the shape of light to tell their part in the narrative, creating this magical realism,” says Zambarloukos.

Natural light was relied upon for around 80% of the shots, with gaffer Dan Lowe incorporating practical fixtures if needed and a few small LED units from Artemis. Textiles, flags, and silks were used, especially in the interiors of the two houses, to ward off unwanted light or reflect light. Muslin on the floor helped capture additional light, and solid black flags created contrast in the shaping of the face when shooting close-ups.

Despite Branagh’s love for stylised filmmaking, he wanted to avoid a documentary feel in all facets of Belfast’s creation. “So sometimes, if we followed that method in the lighting and framing, the visuals needed to be elevated in some way, which we achieved in the grade,” says Zambarloukos.

As with his previous productions, he worked on the dailies grade every lunchtime, this time alongside dailies colourist Jo Barker. “At first, I said, ‘I want this to be quite subtle; I don’t want to go too contrasty,’ and Jo did that so beautifully. But then as we progressed, we kept cranking up the contrast and gloss, so by the time we were grading it with Rob [Pizzey], there were very inky blacks and quite pronounced highlights,” says Zambarloukos. His on-set team from Digital Orchard included Barker, dailies operator Szymon Wyrzykowski, and video operator Mat Lester.

This process of experimentation and adjustment led Zambarloukos to settle on a higher contrast, enhanced grade rather than milky grey, which Rob Pizzey, who has graded many of the cinematographer’s recent films, helped realise. Zambarloukos wanted the “full tones of the whitest white to the blackest black” to balance out the “unobtrusive” composition and framing.

“I then suggested to Ken that we needed a Dolby Vision version, so I called Dolby and they gave us a Dolby Vision HDR grade. It really makes a difference – your zone system is expanded, and your deepest blacks are pitch black,” he says. “I noticed this on Murder on the Orient Express – my first Dolby Vision finish. At the end of the film, if you watch it in Dolby Vision, it actually fades to black, so you just hear Michelle Pfeiffer’s haunting voice as she sings, accompanied by complete darkness. In other theatres, there was some ambient light, and the emotional experience was not the same.”

After shooting large, technical films with Branagh that have seen him take on exciting challenges such as shooting a boat “floating down the Nile” in Chertsey, working in a more realistic environment requiring less technical invention was liberating for Zambarloukos.

“It reminded me that less can be more – you can be quiet, not intrude, and still get the best results. In terms of its simplicity, one of my favourite scenes is when Granny [Judi Dench] brings Buddy back from the theatre on the bus. It embodies Ken’s true love of cinema as a child. It’s all about the amazing dialogue he wrote that Judi performs so beautifully and with such warmth – everything coincided perfectly.

“If you shoot in black-and-white and you have phenomenal performances and an emotional story, the film reveals itself in its brightest and best colours.”