Diversity, Dogs and Docudrama

Across The Pond / Mark London Williams

Diversity, Dogs and Docudrama

Across The Pond / Mark London Williams

Lead image: The Chapman Leonard Diversity Panel headed by (l-r): John Newby ASC, Donald A. Morgan, Patrick Cady ASC (c/o Chapman Leonard)

We’re in the midst of that “advent calendar”-like season between NAB and Cine Gear, with film town events filling the weeks between each expo. Indeed, we’re filing this column shortly after Chapman Leonard’s annual open house, at their sprawling North Hollywood headquarters, and a little ahead of J.L. Fisher’s own open house and BBQ, a couple weeks later.

Indeed, standing on the tarmac on the hot afternoon of the Chapman Leonard event, ICG 600’s Steven Poster and Michael Chambliss strolled by, having left the Local’s own booth around the corner from the main stage.

As they walked past, they expressed faux-alarm at what we might be writing down. They were assured it was all “mostly true.” And then we agreed about the general blur of the calendar, before the briefest of respites before the whammy of Emmy-then-Oscar season - with, as Mr. Poster reminded us, ICG’s own Emerging Cinematographer Awards in the fall as well.

But we get ahead of ourselves.

While the Chapman Leonard event was an all-day Sunday affair, we caught most of its midday section, including a panel on the need for greater diversity among crew folk, and in particular, camera crew folk, up to, and including the DPs.

![2018_CL_Showcase_0123_preview[1] Craig “Burnie” Burns (Applebox Network) & Nichole Huenergardt. (c/o Chapman Leonard)](https://britishcinematographer.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/2018_CL_Showcase_0123_preview1.webp)

![2018_CL_Showcase_0363_preview[1] Chapman Leonard employees – James Razo & Hassan Khan (c/o Chapman Leonard)](https://britishcinematographer.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/2018_CL_Showcase_0363_preview1.webp)

![2018_CL_Showcase_0714_preview[1] Dean Cundey ASC captivates an audience (c/o Chapman Leonard)](https://britishcinematographer.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/2018_CL_Showcase_0714_preview1.webp)

![2018_CL_Showcase_0967_preview[1] Taylor Stoffers & Brian Sergott capture a lively performance (c/o Chapman Leonard)](https://britishcinematographer.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/2018_CL_Showcase_0967_preview1.webp)

In an ironic twist, the panel was all men, but in fairness, that’s because they’d been called in, with about 48 hours notice, to replace the original trio. We chatted briefly with Donald A. Morgan afterwards. Morgan is well-known for his TV work, including the Tim Allen productions Home Improvement and Last Man Standing.

Talking with him after, he relayed how shocked he was to find, after being invited into the ASC, “that I was the third black cinematographer.” Ernest R. Dickerson, who collaborated with Spike Lee on so many of his early works - and who now directs episodes of shows like Bosch and Walking Dead - was the first.

And while it might be startling to consider how long it took for that to happen, since Dickerson rose to prominence in the mid-to-late ‘80s, Morgan says that “now there are six or seven of us.” He also noted there were about fourteen or so female numbers, so things are slowly - slowly - improving.

The aforementioned ICG however - the union to which virtually all ASC members belong - has over a thousand female members: About 15% of its membership, contrasted with the 4%-ish number for the ASC.

The good thing is the conversation isn’t only “saved” for events like NAB, but precisely that it continues at places like Chapman Leonard’s open house, or presumably at the J.L. Fisher event where Women in Media is specifically leading a tour for its members.

"The ICG - the union to which virtually all ASC members belong - has over a thousand female members, about 15% of its membership - contrasted with the 4%-ish number for the ASC."

And speaking of “conversations,” a couple that we’d had earlier ran up against our expanded NAB coverage last time out, so we return to them now.

The first of these was with Tristan Oliver, DP for director Wes Anderson’s delightful stop motion film Isle of Dogs, and an alum of the director’s earlier animated work, Fantastic Mr. Fox. His other stop motion stops have been equally illustrious, with films like ParaNorman, Chicken Run, and all those great Wallace & Gromit shorts to his name.

Of acquiring stop motion cinematography as a specialty, Oliver said it all happened “completely by accident, when I was first starting out - I ran by Aardman to borrow some equipment, and they said ‘what are you doing next week?’ It was pretty much like that.”

Aardman (Studios or Animations, as they variously fill out their official name), was then concocting a short called The Wrong Trousers, about a cheese-eating pensioner and his smarter-than-him dog. Oliver recalls that Aardman was a company of “three or four people then - and they liked me.” He kept freelancing, including work there, and notes that he’d gotten in “on the ground floor when stop-frame achieved credibility.” Plus, “I had a family that was young - and it was a reliable income stream.”

On the differences between doing stop-frame versus live animation, Oliver says “I always like to think there shouldn’t be a difference - and if we’re doing our job properly, you don’t consider you’re watching animation.” But regardless of how captivating the final product, he does acknowledge the practical differences along the way.

“Typically on live action you’d have one main camera - and occasionally a second or third one. But we’re working right on the macro end of photography. It’s often difficult to get light on a character when the camera is so close,” so one of the challenges, he says, is finding “ways to work around the size of the camera. Typically the art department comes in, the set is lit, and changes are programmed in. The set is brought to a point of readiness, and the crew vanishes,” at which point the animator takes over.

That animator then spends “hours and hours in front of the camera, manipulating the puppet (and) doesn’t want to be bothered with anything technical whatsoever - they have a button and press the button. They’re not thinking about anything technical.”

As for that button, it isn’t found on a traditional “motion picture” camera, though: “Our weapon of choice has been a digital still camera - we’re asking (it) to make a coherent sequence of images,” which in turn is “run as if it were a sequence.”

Which all makes sense, when you consider that the entire film is created with frame-by-frame movements of puppets.

Their camera of choice lately is a Canon 1D-X - and there are about “seventy or eighty of them” being used in a production. This is because numerous “small sets” are built, and animated on, simultaneously.

Helping to keep track of it all is Dragonframe software, an industry standard for single frame cinema, with “a camera control page (providing) full control over shutter speed, ASA, whatever. If I’m shooting in stereo, I can pull up left and right eye images, and all my dimming control for lights - up to hundreds of channels.”

And you can also do your color control through the software, which, in its way, brings us to our next DP chat…

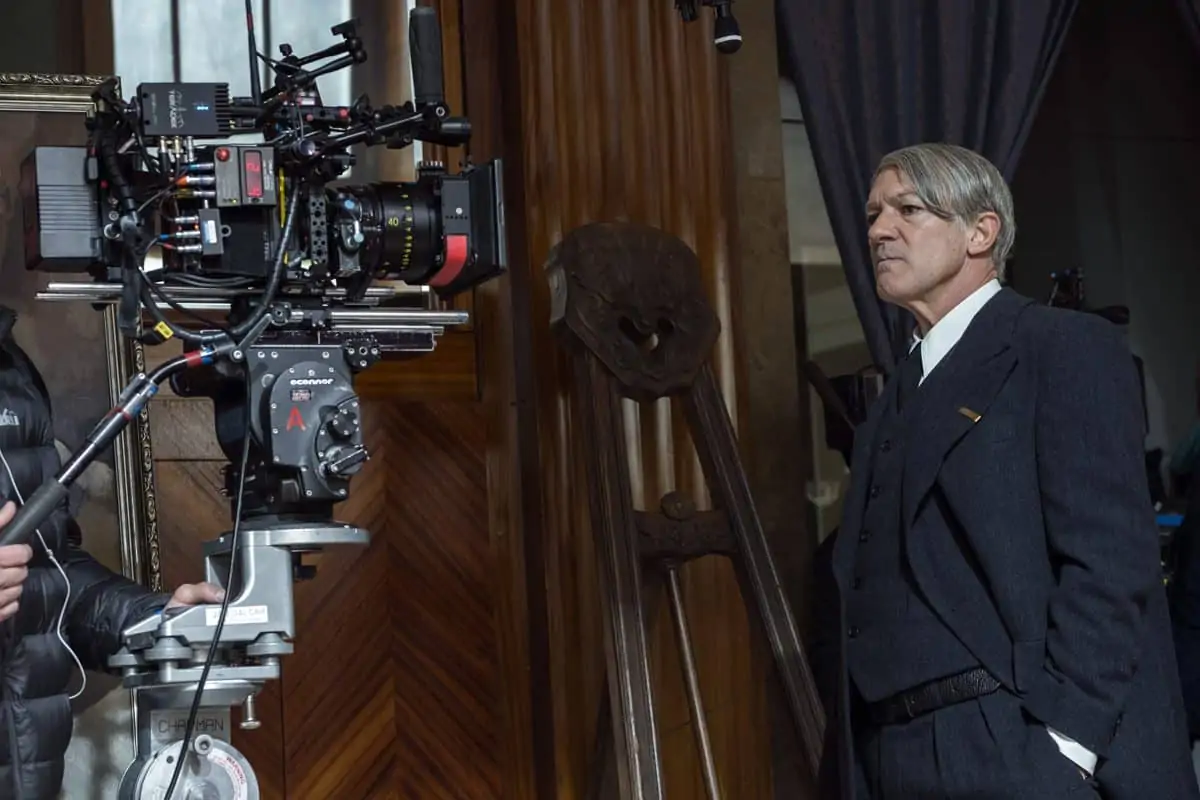

Mathias Herndl has been the DP on National Geographic’s Genius series, and is charged with helping visually recreate the lives of men whose genius lead them to give real-world expression to often intangible, abstract ideas: Albert Einstein, via quantum physics, and currently, Pablo Picasso, attempting to change the “physics” of what could be seen on a canvas, and the colors used to show it.

(National Geographic/Dusan Martincek)

“Last year,” Herndl told us, “in order to capture Einstein's present day storyline, we used Vantage T1 lenses and an energetic, kinetic, moving camera, hand-held stylistic approach. The lenses supported the desired feel by being softer, smoother, slightly vignetting, with halos in highlights, a touch of breathing and unparalleled texture. I like to refer to them as ‘perfectly imperfect.’

“This visual recipe has become a major part of the branded look of our series. But we took our approach to the next level. Picasso's present day storyline is once again shot using Vantage T1s. But in order to help us truly capture the Mediterranean light - which has influenced and inspired the great Picasso to the tune of over fifty thousand works of art - the guys at Vantage outdid themselves again for this season. They custom built one set of T1 lenses which are ‘uncoated’ - built with little to no flare coating on the optical elements inside the lens - specifically for our show. The results in terms of texture, color, creaminess, and flare structure are incredible. I have never seen light break this way before. It is incredibly exciting.

“Our flash-forward storyline is once again shot on ARRI Master Primes. But in an escalation of last year's approach, this season, our camera is not slower, heavier and more classic, but completely still. In a nutshell, Picasso's flash-forward storyline is told in paintings. The frame is set and the story happens within it. If something happens outside this still frame, and is important enough to be shown to the audience, it deserves its own painting to cut to. This stubborn camera adds strength and tension, which serves the exploration of Picasso's character extremely well.

“And I have now had the pleasure to work with Pankaj Bajpai as my colorist for the last three years. He is an incredible artist and craftsman and when it comes to my imagery, truly my other half. I always say that nowadays, if you claim that fifty percent of all cinematography is not happening in the color suite, you're either lying or not doing it right. “

As for how they “do it right,” Bajpai adds that “early on in the project, the conversations Mathias and I had were based on matters such as quality and texture of light. For example, there was a particular spot in Málaga where Picasso derived his inspiration (which) was pointed out to Mathias by (Picasso actor) Antonio Banderas, who also grew up in Málaga, and in Picasso’s neighborhood. That spot became a focal point of inspiration for the look of the show. The goal is to create imagery in the photography and color that resonates with the experience of having walked through an art gallery. It’s an appreciation of the vicissitudes of being a painter who is a creative genius.”

“Vicissitudes” is always a good word to use when it comes to the unpredictability of making art. Our calendar ahead, at least, remains someone knowable, so we’ll see you in a month.

In the meantime, don’t let the vicissitudes keep you from writing in: AcrossthePondBC@gmail.com

Comment / David Raedeker BSC / member of the BSC sustainability committee