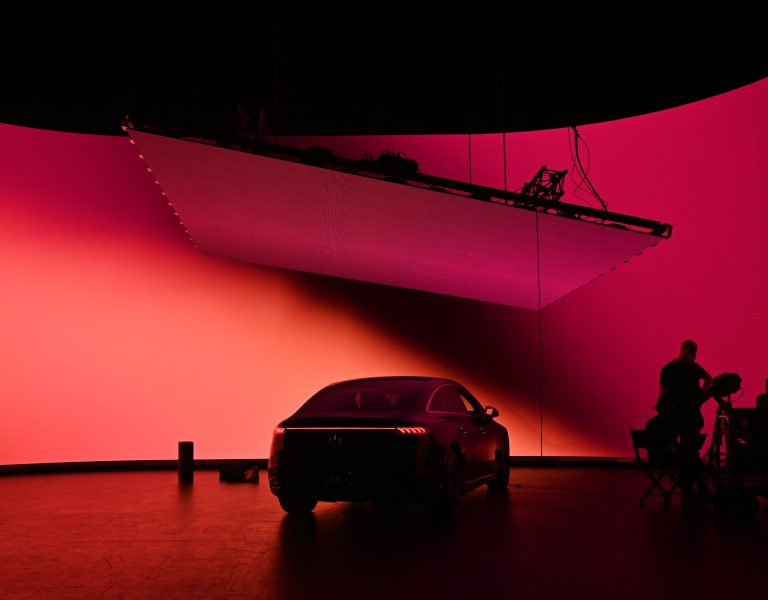

DPs, VFX supervisors, and producers discuss the myriad of factors to consider, including shooting schedules, bespoke versus existing LED stage, the needs of the scene, and the hot topic of the year – copyright issues as they relate to AI-generated content.

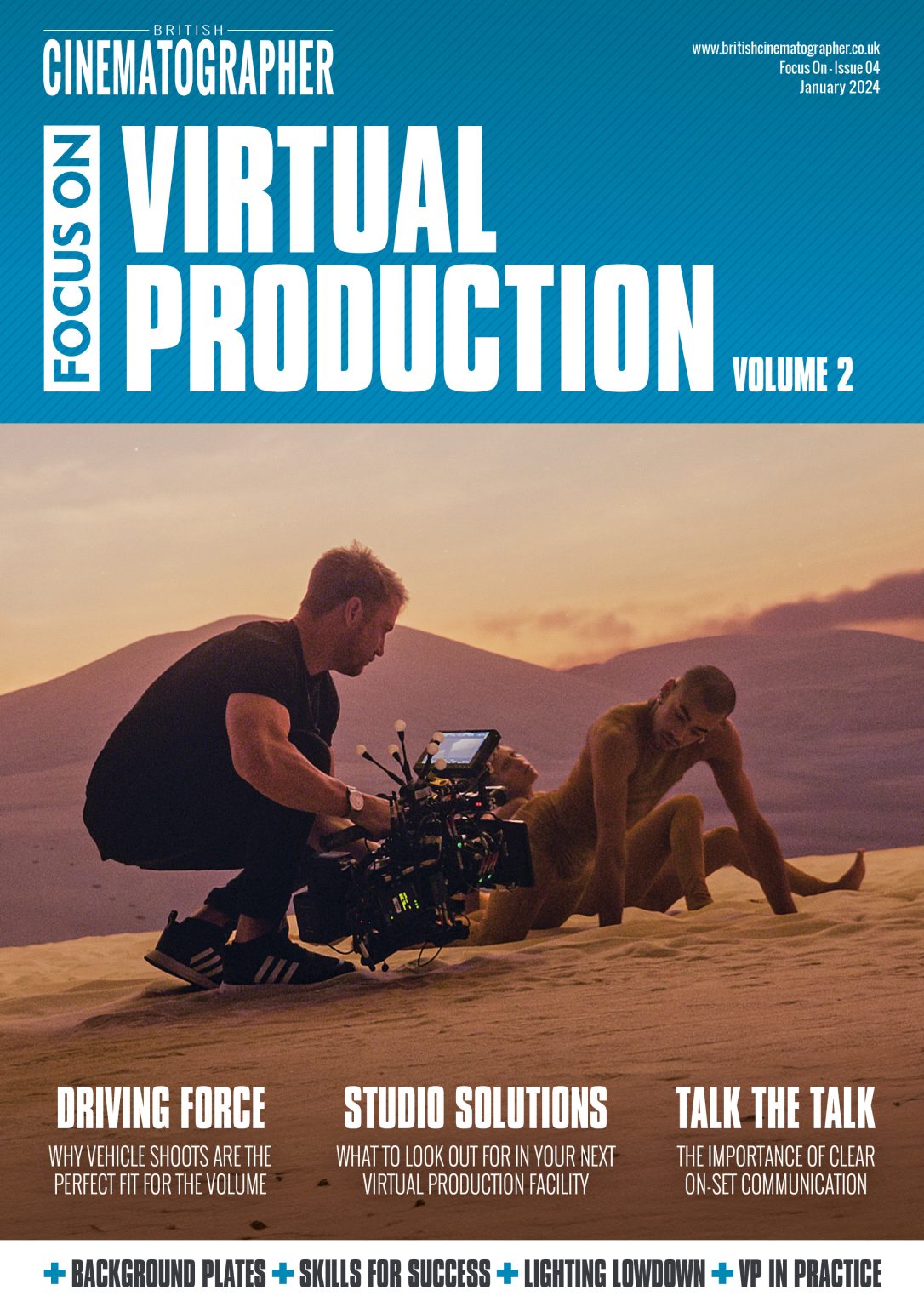

As more productions consider virtual production, we explore some of the elements that should be considered when it comes to content used on the LED volume. Aside from gaining a solid understanding of the VP workflow, the biggest factor is time, says London-based Driving Plates producer, Ian Sharples.

“The biggest element is time. A lot of the technical work is about prepping footage, rendering files and moving them around, getting them into the right codecs and onto the playback servers. You can’t decide to use a volume the night before,” Sharples says. “It takes two-three weeks to coordinate with the DP, director, VFX supervisor, and the LED screen company to get everything ready for the actors to sit inside that car [for a driving sequence].”

Offering the largest content library of HD, 4K and 6K 360-degree 2D plates of driving footage (shot in 42 countries over the past 12 years), Driving Plates also offers bespoke shooting for driving sequences, either as a standalone unit or embedded with the second unit. “We can put a crew out anywhere in the world and our equipment flies with us. We use standard unmodified vehicles with a choice of cameras, but most often nine RED Komodos with near-50k horizontal resolution,” says CEO and producer M. Shawn Lawler, who observes that in spite of the growing popularity, LED studios are not appropriate for all productions. “Our plates work for VFX compositing and LED.”

Moreover, with how quickly VP technology has developed in just the past 3-4 years – precipitated partly by COVID-19 grounding on-location shoots for months on end – keeping abreast of the latest developments is key. Driving Plates regularly consults with clients to advise and educate filmmakers. “Because we’re working with LED stages around the world every week, we see the evolution in real-time in the playback software, pixel sizes they’re using now, the manufacturers of LED panels, the colour system,” adds Sharples.

Their work also gives editors a reliable backup if their main footage does not provide exactly what is needed in post. Once the main unit has shot a sequence, “we’ll go through with the 360-degree array and grab everything. That way, they have a backup from the day that sequence was shot, which provides perfect continuity with the same lighting conditions and in the exact same setup they had,” Lawler says.

A filmmaker’s consideration also hinges on whether the content will be used as additional source of lighting to augment traditional lighting fixtures, called “out-of-vision LED” or “image-based lighting” (IBL), as VFX and VP supervisor Jim Geduldick explains. “Basically, you’re using it as an interactive lighting source that is a different approach to an in-camera with frustums via Unreal Engine. It provides the reactive lighting to your actors, props, and the set that you would normally get from a daylight exterior or other traditional practical film lights.”

The type of content also depends on whether one will be shooting on an existing LED stage or a bespoke stage. “If you’re going into an existing stage, you may be limited by the design of that LED wall, the configuration and camera tracking, and what you can and cannot do within that space. Sometimes lighting, sound, and camera tracking can get tricky. So, you have to make sure your content can be married into that space seamlessly,” remarks Geduldick.

For Gangs of London DP Björn Charpentier SBC, the decision to shoot the crucial 20-minute driving sequence in the season two finale on the volume was driven by director Corin Hardy’s desire to make it more visually interesting. “Because we shot in November/December, there was limited daylight. We wanted to have natural reflections, everything built in-camera, and have better performance from the actors,” says Charpentier. “Since they’re not looking at a green screen, they can really react to what they see on the road and the cars behind them. So, it’s very immersive for the actors,” he adds.

The volume unexpectedly saved the day during one of the sequences where a character – spoilers – bleeds out of his eyes and dies of horrific food poisoning right in the car at a gas station. Since there was a lot going on, they soon ran out of time shooting on location. “Because we had so many stages of makeup – first the eyes then the nose and the ears – all of that took so much time. So, we had second unit shoot a 360-degree plate of the gas station and got all that dialogue and makeup changes done in the volume studio,” Charpentier explains.

Shooting in the volume for part of her current project, DP Dale Elena McCready BSC NZCS thinks a lot of it comes down to the shooting schedule: “You’re dealing with a lot of technical and logistics when shooting driving sequences on-location. If your driving scene focuses on the actors talking inside the car, the background might be out of focus and using stock footage could be the way to go,” she says. “If it takes place in an urban environment with a lot of traffic, then you may have to use a multi-camera array to maintain continuity.”

McCready boils the decision-making matrix down to time and money: “Do we shoot it ourselves or send a team over there? Can we spare the crew and the rigging to do it? If stock footage suits out needs, we can save time and money because we’re buying the footage rather than the cost for the day of filming.”

Even though shooting on the volume shifts the VFX into a pre-production model rather than post, it gives McCready more control to deliver the art direction and style that works best. “I have a lot of control over filmed material, and the ability to shoot the foreground and background in-camera live allows me to fine-tune the lighting to a better degree and move the camera in a more flexible way,” she adds.

The biggest issue looming over VP in Geduldick’s mind is what everyone has been talking about all summer with the duelling strikes in Hollywood – AI. We are still in the very early stages of exploring this issue since there are currently no regulations. “As of today, you cannot copyright AI-generated content. If you create 2D moving or still assets that are generated off AI, it can be a big legal issue. Some studios don’t allow the use of AI content because you cannot always trace back the copyright,” he says.

We are not talking about stock footage companies in this case, as those are usually licensable. “Adobe Stock owns the generative AI software Firefly, so they own the copyright to that material,” Geduldick adds. “The most important thing is to know where your content comes from and to be able to prove to your client how the content was generated, whether you created it by shooting the plates or doing the CG yourself, or that you have licensed that content,” he cautions anyone dealing with licensing content for VP.

_

Words: Su Fang Tham