Doing the trick

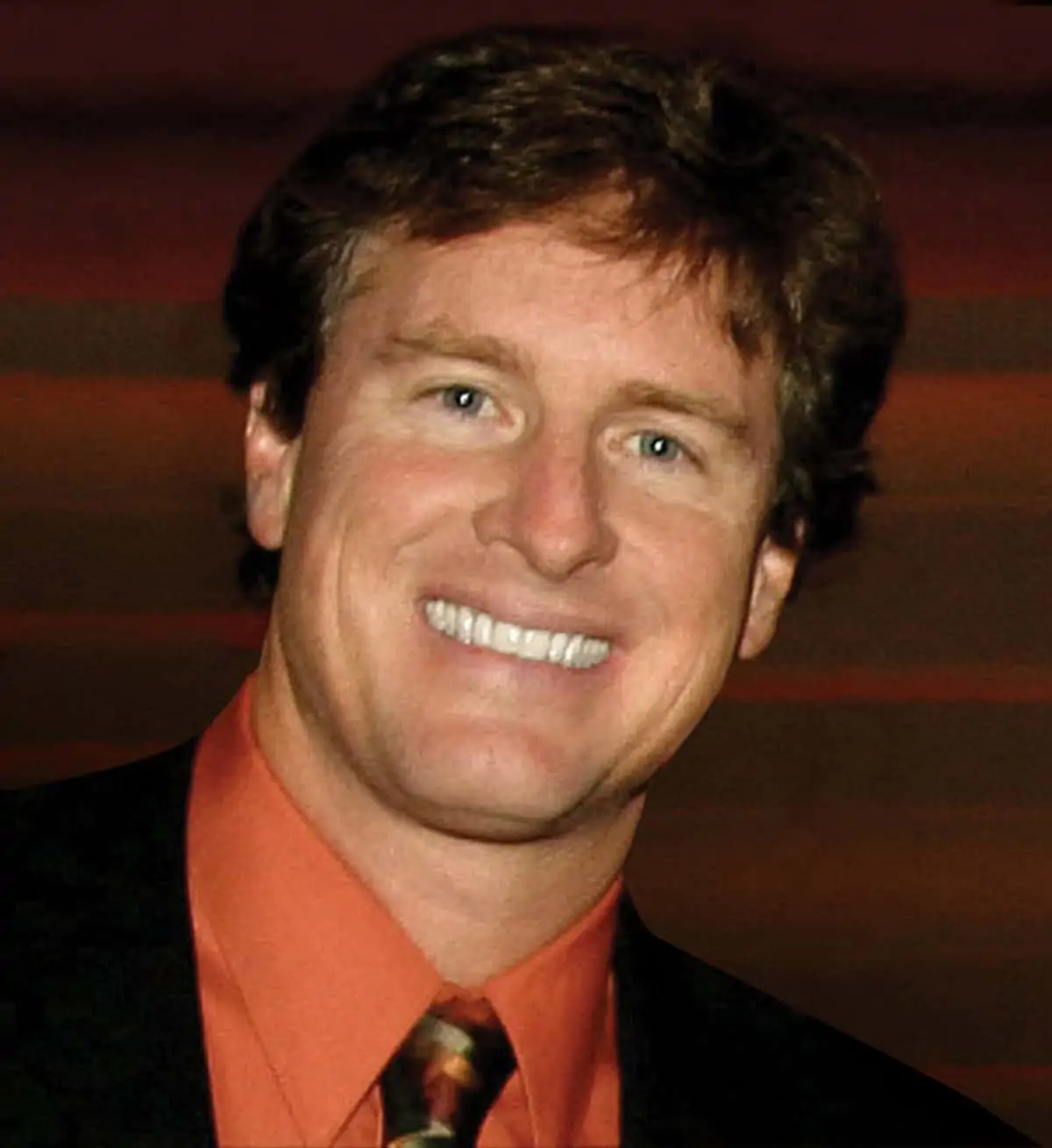

Clapperboard / Steve Begg

Doing the trick

Clapperboard / Steve Begg

BY: Michael Burns

One of the leading practitioners of the arts of special effects and VFX working today, Steve Begg was the visual effects supervisor on the recent clutch of 007 James Bond blockbusters, and has worked with directors from James Cameron to Christopher Nolan. It’s clear that talent and sheer drive have played no small part in getting to this high level – as well as some chance meetings.

Born in Edinburgh in 1960, Steve Begg had a passion from an early age for a particular kind of filmmaking. “As a kid I was inspired by a lot of the Gerry Anderson and Ray Harryhausen type of special effects work,” he says. “It made such a big impact on me. I knew had to get involved with that.”

Thus inspired, Begg invested in some hardware – at the tender age of 12. “I got myself a Standard 8mm camera, and started playing about with multiple exposures, stop-motion, all sorts of tricks that I could do with that camera. That’s how I sort of kick-started myself.”

Aged around 16, when he started working and earning some money, he bought himself a Bolex H16, a 16mm camera. “I pushed that thing as far as I could,” Begg recalls. “It was a semi-professional camera, and I learned a hell of a lot by just playing around with it. I actually took a lot of that experience with me into a professional environment later on. Around that time I plucked up the courage to meet, through a mutual friend, Gerry Anderson. I showed him a couple of my 16mm films.”

Anderson seemed suitably impressed and told the teenage Begg to keep in touch: “Which I did, to the point of pestering him,” he admits.

Made redundant from his day job as a payroll computer operator in 1982, Begg almost immediately got a phone call from Anderson, who asked him if he could draw. Impressed with the storyboards he received in reply, Anderson took Begg on-board as a designer and effects assistant on his show, Terrahawks (1983-86). “It was like going to film school for special effects,” says Begg.

However, Anderson wasn’t particularly happy with his existing special effects technician on the show, and offered Begg a chance to take over. Says Begg, “I gulped, and said, ‘Yes’. I was so full of piss and vinegar that I thought I could do anything.”

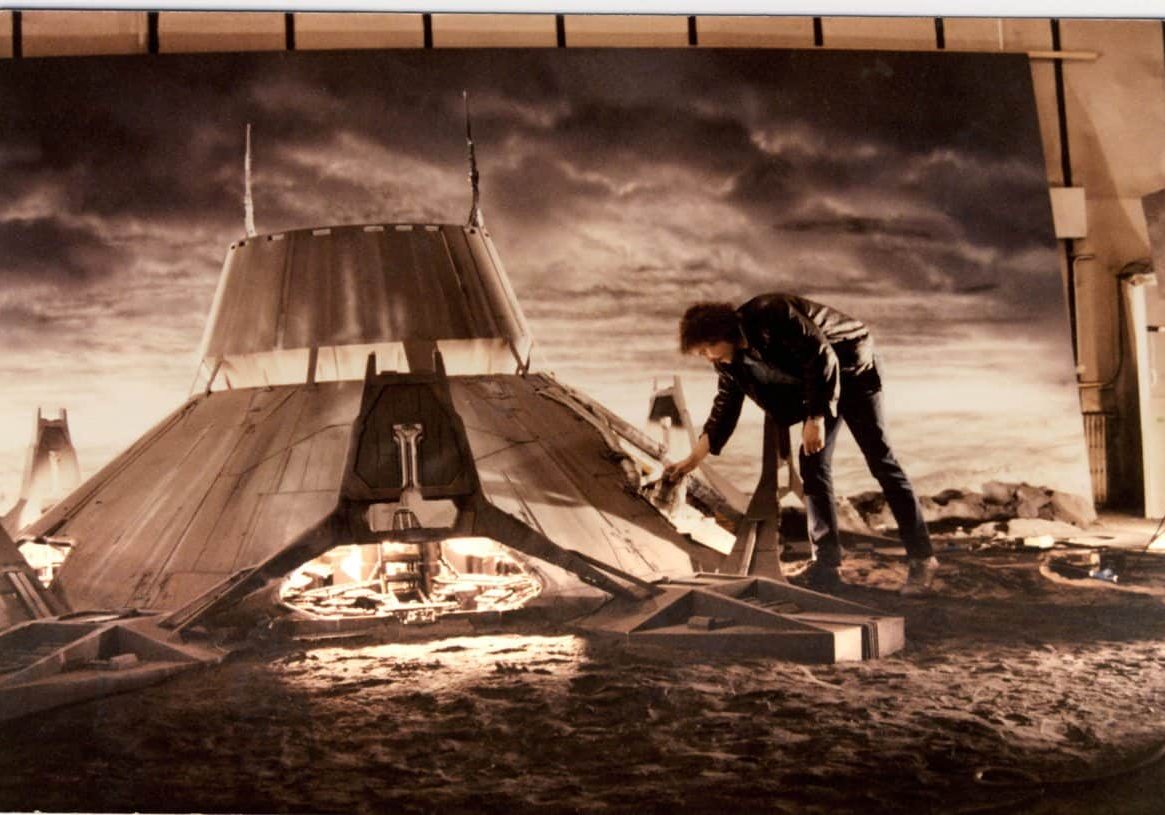

Given the reins of a professional special effects unit on Terrahawks, Begg’s on-the job effects education really went into high-gear. “Every single shot was a miniature effect, or a special effect of some sort. Shooting at high speeds, slow speeds, stop-motion, and all sorts of tricks,” he says.

Begg worked on Terrahawks for two years. Through various contacts, he was then “fortunate enough to meet with the American effects team on James Cameron’s Aliens (1986, DP Adrian Biddle BSC).”

“The Skotak brothers [Robert and Dennis] got me on board Aliens to help them out,” he explains. “I was doing storyboards, and occasionally they’d let me take care of a smaller effects unit. This typically involved creating some background plates that were going to be back-projected on the live action sets, usually with Sigourney Weaver in front of it. It was quite a responsibility and I’m very pleased that they allowed me that opportunity.”

Begg continued to work over the next decade with Anderson, including on commercials.

“I kept my hand in with Gerry. I was very fortunate, courtesy of Terrahawks being screened on TV, to meet Derek Meddings. He was an longtime collaborator of Gerry Anderson, and was the special effects guy responsible for Superman and the 007 James Bond films, and I ended up working with him.”

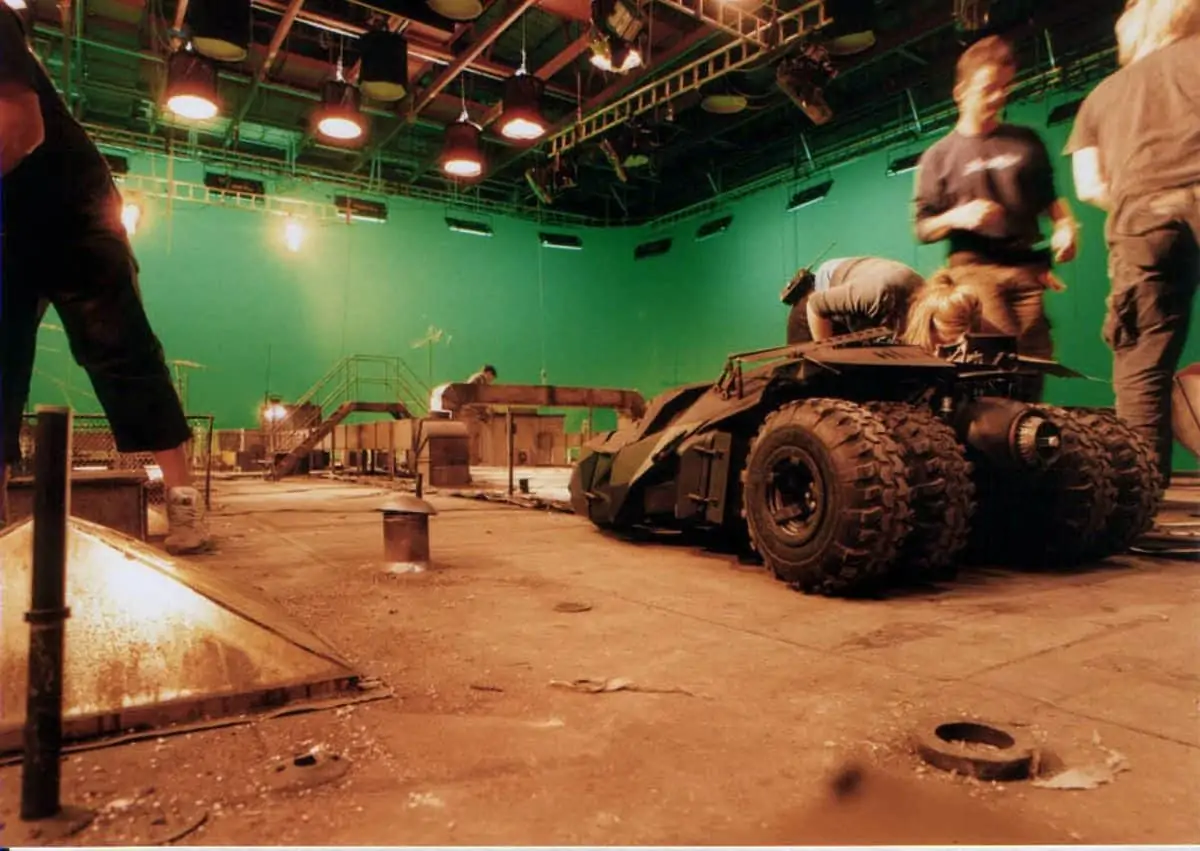

"I went on to supervise the miniature work on Batman Begins. The miniatures were anything but - they were quite colossal. Even as a third-scale model, the Batmobile was five feet long... it could break your leg if it hit you."

- Steve Begg

Oscar and BAFTA-winning Meddings had set up his own visual effects unit, The Magic Camera Company, and Begg worked with him on films including the first Tim Burton Batman, as well as doing digital animation on GoldenEye (1995, DP Phil Méheux BSC). “It was great,” Begg says. “As with Gerry Anderson, and fellow SFX collaborator Brian Johnson, Derek was one of my heroes when I was a kid, so to actually end up working with him was terrific.”

Begg’s first experience with CGI was in 1998, as a visual effects co-supervisor on Lost In Space (1998, DP Peter Levy). (Begg is also listed on the film as 2D digital artist and model unit director).

“By the time I was the main visual effect supervisor on Lara Croft: Tomb Raider (2001, DP Peter Menzies Jr.), we were almost entirely using CGI visual effects. Becoming the overall supervisor on these big action effects movies was a highlight. Around this time I met the special effects guy, Chris Corbould, who was doing the Lara Croft work. I became friends with him, and I went on to supervise the miniature work on Batman Begins (2005, DP Wally Pfister ASC). (Corbould was special effects co-ordinator on the Christopher Nolan film). The miniatures were anything but - they were quite colossal.

“Even as a third-scale model, the Batmobile was five feet long,” he adds. “It was radio-controlled and could break your leg if it hit you. They were models and miniatures, but they were not small – I think we were the first to coin the phrase ‘maxitures', or ‘bigitures' for that sort of stuff.”

After this, Begg was introduced to the team working on the Daniel Craig reboot of the James Bond film series. “That led to me to initially do the miniature work on Casino Royale (2006, DP Phil Méheux BSC),” says Begg, who would subsequently become the overall visual effects supervisor on the movie, which he considers another career highlight.

“It was great – a really lovely hybrid of CGI effects, real effects, stunts and miniatures,” he recalls. “I try to use all sorts of techniques when I can, and when they fit the bill. I enjoy mixing stuff, because I feel you get the best of both worlds.

“For example, the big building sinking at the end of Casino Royale – you knew it was real in one way or another, albeit a miniature, but courtesy of digital effects we put it into real background plates and real plates of Venice. So we had the best of both – miniature effects with a little help from CGI effects.”

Begg feels that this approach gives a sense of realism when it comes to the compositing stage. “I do think if you can start with something real and then help and augment it with CGI, then you get a much better effect.”

Other Bond movies followed – Begg was overall visual effects supervisor on both Skyfall (2012, DP Roger Deakins CBE BSC ASC) and Spectre (2015, DP Hoyte van Hoytema FSF NSC) “And in charge of miniature shooting, if there was some,” he reminds us. “On the last one, Spectre, we had no miniature work whatsoever; it was all CGI. But to be honest the subject matter didn’t lend itself to miniatures.”

In terms of industry accolades Begg was given the award for Outstanding Contribution to Craft by BAFTA Scotland in 2013, whilst in the 2016 year he was recognised for leadership and the advancement of visual effects in the UK as part of the inaugural UK Visual Effects Society Awards.

“I was particularly chuffed with the award from BAFTA Scotland,” he says. “The VES Award was great fun, and it was great to be considered by your peers.

“Obviously the UK VFX industry is very vibrant at the moment,” he says. “I think the weaker pound and exchange rate helps, as well as the amount of very talented and experienced people here. The thing is though, the work is not country-centric. It’s based on money. So the talent will have to go where the money is – at some point it will shift away from here.”

At the time of writing Begg was on the set of Liam Neeson’s latest vehicle, The Commuter (2017, DP Paul Cameron ASC). “It’s a thriller, set on a train,” he reveals. “But just before I got involved with that, I helped Gerry Anderson’s son, Jamie Anderson out with a project called Firestorm, which used marionettes and model, special effects and digital effects. It kind of felt I was going back to my roots.”

He suggests those who might like to follow in his footsteps get on a computer and study 3D or 2D packages, put together a showreel and try to get work in one of the big VFX facilities in London.

“Looking back at the route I came, I was fortunate,” he admits. “It didn’t feel like it at the time, because it took a hell of a long time to happen, but every few years something profound would happen and then push me in a certain direction. I was lucky.

“It’s funny – when I was a kid I wanted to do two things,” he muses. “One was to work with Gerry Anderson and the other was to work on a James Bond film. It’s amazing that I’ve actually managed to do that.”