CLOSE ENCOUNTERS

Shelly Johnson ASC / Greyhound

CLOSE ENCOUNTERS

Shelly Johnson ASC / Greyhound

BY: Ron Prince

In a thrilling WWII story, inspired by actual events during the Battle Of The Atlantic, Captain Ernest Krause leads an international convoy of merchant ships across the treacherous ocean to deliver soldiers and much-needed supplies to the Allied forces fighting in Europe. Written by and starring Tom Hanks, the movie is available to watch on the Apple TV app.

The $50m production was directed by filmmaker and former DP Aaron Schneider ASC, and shot by renowned cinematographer, Shelly Johnson ASC. It is based on the 1955 book The Good Shepherd by C. S. Forester, a nautical war novel depicting the difficulties of the Atlantic war: the struggle against the sea, the unseen enemy, and the fatigue brought on by constant vigilance.

Set in the winter of 1942, during the early days of the United States' involvement in WWII, the movie follows US Navy Commander Krause on what turns out to be his first war-time assignment in command of a destroyer, the USS Keeling, call sign "Greyhound", and his leadership of a multi-national escort group defending a 37-strong flotilla being hunted by a wolfpack of German U-boats. Unlike the prototypical hero, he must battle his own self-doubts and personal demons to be effective.

The cinematic evocation of this single, 72-hour moment in the Battle Of The Atlantic is powerfully realised. The enormity of the decisions and the procedural complexity of commanding the convoy are conveyed with historical accuracy and technical detail. Although the events and characters are fictionalised, the story depicts the real difficulties faced in wet and freezing conditions, and stresses just how attentive the men on-board, especially the sleep-deprived commander, had to be in dealing with sonar/radar equipment and unreliable communications between different parties.

Greyhound was scheduled to be theatrically-released in the United States on June 12, 2020, by Sony Pictures Releasing, but was delayed due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The distribution rights were then sold to Apple TV+, which has released the film on its Apple TV app.

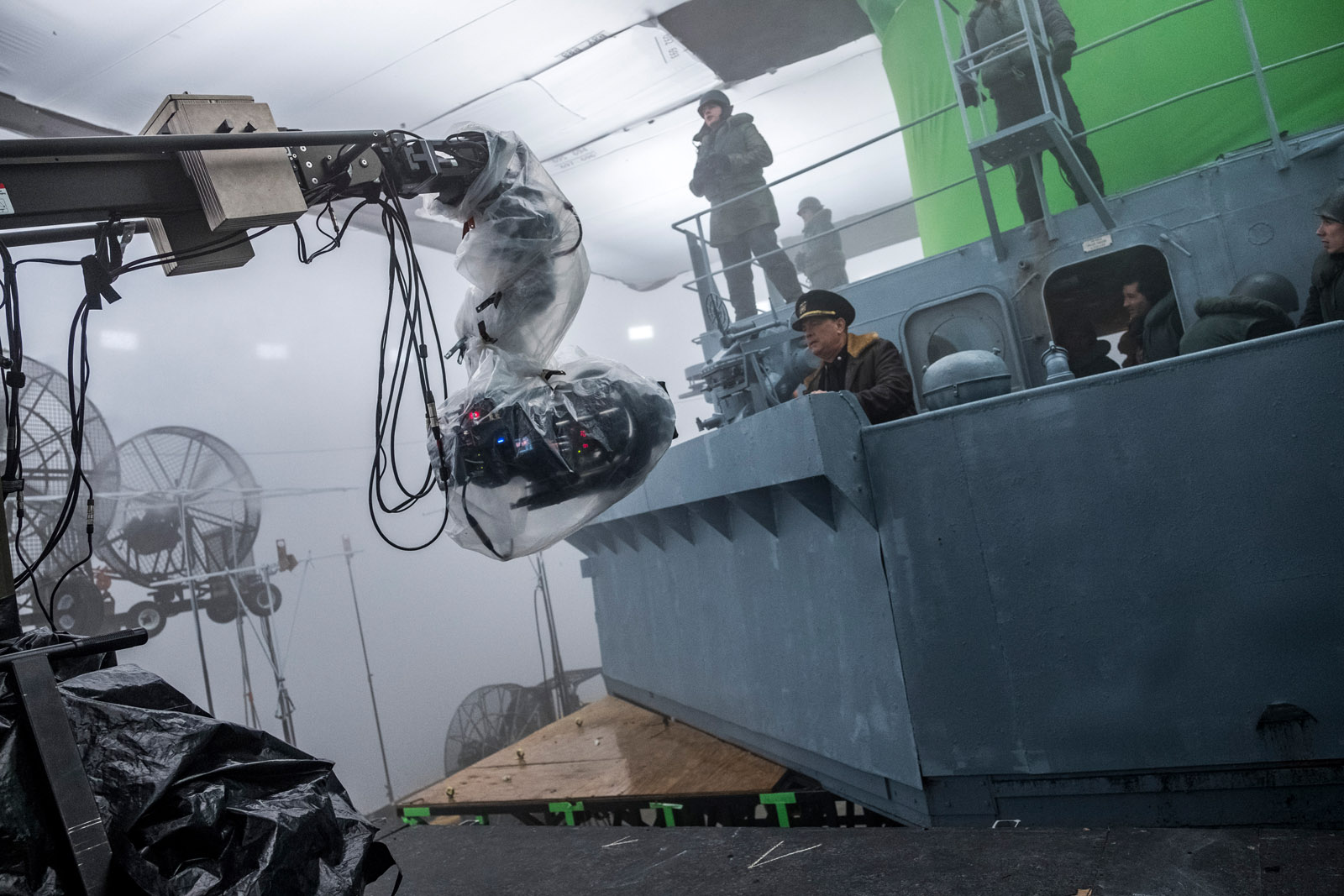

Based in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, pre-production on Greyhound began in January 2018, before principal photography took place over 40 shooting days between March and May. As Schneider was keen on authenticity, part of the production took place aboard the USS Kidd, a WWII Fletcher-class destroyer now permanently moored as a museum piece in the banks of the Mississippi River, and also on meticulously designed sets constructed at Celtic Media Center. These included the ship's bridge and surrounding deck - built on a programmed gimbal to simulate the swell of the sea - plus the Command Information Center, the captain's quarters and various adjoining passageways, which were static and freestanding.

Depicting the real-thing required Johnson to learn a great deal about the practices and procedures on-board a wartime destroyer, as well as how the ship itself manoeuvred around the flotilla in high seas. Whilst many cinematographers compile general story and colour arcs in advance of their work, Johnson created what he calls a "manifesto", detailing scene-by-scene changes of camera and lighting "to make every shot speak as loudly as possible."

"Greyhound was a unique and unusual project because most of the film takes place within the bridge of the ship, following the decision-making process of the ship's captain and crew, often under extreme stress and in ever-changing sea and lighting conditions," says Johnson, whose credits include Hollywood blockbusters such as The Wolfman (2010), Captain America: The First Avenger (2011) and Percy Jackson: Sea Of Monsters (2013). "This film was anything but typical of the Hollywood tradition, and would not conform to any sort of established visual or production plan either, which I found both challenging and freeing at the same time."

Along with Greyhound, Johnson was recently the DP on two additional movies slated for release in 2020, Honest Thief directed by Mark Williams and Bill & Ted Face The Music, directed by Dean Parisot. Ron Prince caught up with the cinematographer as he hunkered down in this Santa Barbara home, to discover more about his work on Greyhound.

What were your first thoughts about the script?

SJ: I thought it was a very interesting story and great for a film. Tom is a self-confessed WWII enthusiast and historian, and I really liked his idea of basing the story around Krause's experience and inexperience, what he does and doesn't know. The story goes through incredible peaks and valleys, swells of hope and desperation, with never a moment's rest, in an incredibly tense situation. He had penned it with a lot of procedural details - with dialogue about compass headings, rudder commands, ranges to targets and torpedo trajectories - and much of it was based around the audience needing to absorb the inner drama.

"To me, the expressive character of the cinematography was the changing light and the camera performance. So I wrote a long document and broke the whole movie down scene-by-scene in regard those elements as a visual manifesto."

- SHELLY JOHNSON ASC

What were your initial discussions with your director Aaron Schneider?

SJ: I knew Aaron back when he was a cinematographer - a very good one I might say. We had met at events at the ASC Clubhouse and I knew his work in episodic television and features. So when he called and asked me to come for a meeting I was absolutely tickled.

He explained more regarding the procedural component of the story, but the first thing we talked about was an early scene in Close Encounters Of The Third Kind (1977, DP Vilmos Zsigmond ASC HSC) set in the air traffic control room, when the air-traffic controllers converse with the plane crew over the radio and listen-in to what they are seeing in the distance from on-board. This is what Greyhound was all about - the evocation of an unseen enemy.

The second thing Aaron told me was that he expected his cinematographer and first AD to learn as much as they possibly could about sonar tracking, radar, maritime weather, how a crew would plot and execute a strategic engagement, and the way a destroyer manoeuvres through the ocean. His reasoning was that during the production, he would be very involved with cast, and providing for the audience an understanding of these details was fundamental to us getting an authentic and compelling drama on the screen.

Did you consider any references?

SJ: This was a unique story, with a participatory camera that would be up-close with the actors, particularly Krause. We looked at Das Boot (1981, dir. Wolfgang Petersen, DP Jost Vocano BVK ASC), which was most like our film regarding its subjective immersion for the audience. However, there are not a lot of sea-going movies that have the same sort of internal focus and action as we intended.

In reality, I took most of my cues by how we wanted the film to feel. This movie was written in such a very different way, it had to feel authentic, with no false Hollywood tone. We knew Tom would deliver in his performance, and it meant the rest of us turning up with our A-game so that we could keep up with him and what was going on in Krause's head.

To me, the expressive character of the cinematography was the changing light and the camera performance. So I wrote a long document and broke the whole movie down scene-by-scene in regard those elements as a visual manifesto.

Tell us about your choice of cameras, lenses and aspect ratio?

SJ: When it came down to focussing on the visual intent, for Aaron, the story was about the faces, but he did not want any distortion in the image. Being a cinematographer himself, he asked me about shooting in large format and the use of spherical lenses in this respect. I agreed with him that shooting widescreen would give the production a textural, cinematic feel, and also allow us to do wide close-ups, with one or more characters in frame at the same time.

After testing the available options, we settled on the Panavision DXL1, based around the RED Dragon 8K Vista Vision sensor, shooting for a 2.39:1 extraction, using Panavision Sphero 65s. Those lenses are very popular and we got a set about three days before we started shooting, so I had very little time to get to know them, and how they would take to our lighting.

But, right off-the-shelf, those lenses and that camera were our look - the pairing delivered a very sweet and deliberate tone, like the right guitar and amp. I was very impressed by the Sphero 65s' subtle aberrations, their rounded capture properties, pleasing flesh tones and soft, classic overall look. I liked the way they gathered the atmosphere and veiled the highlights of the incandescent lamps on our interior sets. And, I was blown away by how the camera and lenses together handled the mixed warm and cool colours of the overall lighting - all without needing any filtration on the image.

We mainly shot with 35mm, 40mm and 50mm focal lengths, but went with a 24mm for a handful of wide close-ups. The Sphero 65s are small, and this meant the camera package was of a decent size to fit-in amongst the crew and actors in the very tight confines of the bridge.

As we had many dark scenes, I typically rated the DXL1 it at 1000ISO, and also played with the shutter angle to get the correct exposure. This also helped us be fiscally responsible with the lighting budget. For the "red scenes" in the sonar room, I cranked the ISO up to 1600 or 2000, and was not averse to any noise this introduced, as it had the textural feeling of film grain and was expressive.

Did you develop/use any LUTs for the production?

SJ: I used one base LUT that I developed a few movies ago, which maximises the sensor's response and puts the image in a good place to start grading. It has some desaturation, but not much, with good colour tone separation, and it holds the highlights well. Essentially, it allows me to overexpose and open-up the camera a little to capture shadow detail.

What's your on-set workflow?

SJ: I have evolved a filmic style of workflow and monitor the exposure myself on-set. I prefer to work without a DIT, and to put that budget into proper dailies grading. On this film the dailies were managed by Technicolor from a nearby suite on the lot at Celtic Media Center. At lunchtime, they would take footage from the morning's shoot and grade according to my notes. By the time we wrapped, I could go to the suite for an hour or so, view and comment on rushes, and also give my instructions for the material we had just shot in the afternoon. Every morning I would see stills of what had been done overnight. It's an efficient way to work, away from the hustle and bustle of the set, and means editorial gets material graded the way I prefer.

Who were your crew?

SJ: We shot Greyhound largely handheld thanks to the masterful talents of two venerable camera operators - Don Devine SOC and George Billinger SOC and their focus pullers Michael Charbonnet and Ryosuke Kawanaka. Our grip/electric crews lead by Bob Babin and gaffer Bob Bates were also up to their usual stellar standards and approached their jobs with creativity and an indomitable spirit that transformed our small set into a living and ever-changing environment. I was so fortunate to have these people as part of my collaborative crew and will forever be in their debt for their efforts.

I must also mention the VFX supervisor, Nathan McGuiness - he did an unbelievable job in putting the ships on the water, and in making the CG VFX and live action coalesce. We worked very closely together. He grew to understand how the movie was shot, the lighting changes, and added to that. I think Greyhound took on more of an epic quality because of his work.

What was your camera movement strategy?

SJ: Except for a flashback scene to a hotel, and exteriors around the USS Kidd, the movie was predominantly handheld, with some Steadicam. We went handheld, on the shoulder, as it was expressive of Krause's human experience, and I felt it was the best way to put the audience on the bridge. It also had the advantage of freeing-up the camera from the sway and swelling motions of the gimbal, and gave us good manoeuvrability around the bridge.

Having shot on the gimbal, Don and George did a wonderful job in harnessing their muscle memory to mimic the rocking of the ship in-camera when we subsequently shot on our static, freestanding sets. Their performances, along with our focus pullers, were just as important as the actors, and I am in awe of their impeccable work.

For the medium exteriors we shot around the USS Kidd. We had to get 50ft above the waterline to see the deck of the bridge, so we used a remote head on a 75ft Technocrane that was fixed to a barge on the river. On separate barges we also had wind and water machines, plus construction cranes suspending silks and greenscreens. All-in-all there was quite a tangle of gear in our own flotilla on the Mississippi.

On these exterior shots, we had to give the impression of a ship moving thorough the sea, sometimes with 30ft and 40ft pitches over just a few seconds. To achieve the effect of being in swells at sea, I remotely operated the roll axis, with Don on pan and tilt.

Please give us some insight into your lighting plans?

SJ: Overall we wanted an expressive naturalism. Along with the camera moves a lot rested on the achieving right lighting. Even though we were shooting on-stage I made every endeavour to make it feel real.

The Greyhound was always moving in and around the convoy at different times of day and night, which meant the light changing all of the time. It was never just from one direction. So we necessarily needed interactive lighting that we could animate as required, and the skills of my lighting crew were very impressive.

For example, we surrounded the set on the gimbal with white muslin in a huge horseshoe shape, with more muslins above, and shone arrays of ARRI SkyPanels through these. We also had moveable soft boxes, again with SkyPanels, if I ever needed more directional light.

The great thing about the SkyPanels is that you can colour mix them and programme the illumination as you need it. This was where my manifesto proved very helpful. I could cool the lighting between midday to late afternoon, go even cooler on the dusks, create a greyness to the night scenes, and make the dawns very cyan. We could also programme fire, explosions, star shell bursts and muzzle flash effects all in tune with the swell of the gimbal, sometimes give the impression of the ship turning around. We generally lit the interiors of the ship with incandescents, augmented with small LEDs.

The beauty of shooting "whitescreen" using the muslins, meant that it was much easier to light and much easier for the VFX teams to deal with in post-production than the green spill associated with traditional green screen.

What were your working hours?

SJ: We worked five-day weeks, 12-hours-a-day, with a break for lunch, nothing crazy. I would start and end each day reviewing the rushes, and spend some time on weekends creating temp VFX comp-stills, to see how the VFX elements were working with my live-action lighting. For me the shooting day is very physical, and the weekends were also a time to relax, recharge and think about what was coming next.

Where did you do the DI grade?

SJ: I completed the grade with colourist Bryan Smaller at Company 3 Los Angeles. He has a great eye, and like my crew, he was similarly willing to go all-in. Because of the Covid-19 outbreak, it was required that much of our work be carried out remotely, either from my home or isolated in a theatre on the Sony lot. Bryan and I finally got to grade in the same room for the final two days of the DI in late June.

How challenging was this as a movie?

SJ: All movies are a challenge. I have been a DP for 34 years, shooting in mud, mountains or underwater, being either cold, hot or wet. But, I am no stranger to being uncomfortable or away from home. It's now become a lifestyle.

On this movie, whatever distractions might have come up - about the cameras, lenses and lighting - the initial visual goals that Aaron and I made regarding the cinematographic storytelling, were the food we had to keep swimming for. We had to stay focused on the narrative in a highly-technical environment - that was probably the greatest challenge.

Any final thoughts?

SJ: Looking back - beyond shooting 8K large format and the cool LED lighting set-up - the talent and dedication of the cast and crew are what brought life to this project. Also, every day, as I climbed up the scaffolding and onto the gimbal, I quietly said to myself, "I am very lucky to have the job I do, and I have a lot to be thankful for. I am going to give it everything I have."

Comments are closed.