GILT-EDGED

Rob Hardy BSC / Devs

Gilt-edged

Rob Hardy BSC / Devs

BY: Ron Prince

"Devs defines what great art is - the epiphany that changes what you thought you felt about what you were convinced you knew. Alex's work on this is in a completely different universe, and made me think that if Stanley Kubrick was alive, it would be his favourite film this year," commented Steven Spielberg about the TV sci-fi thriller miniseries created, written and directed by Alex Garland. The show premiered on March 5, 2020, on Hulu, as part of FX Networks on Hulu, and then on BBC. Devs is also available on BBC iPlayer for the next 12 months.

The eight, one-hour episode series centres on computer engineer Lily Chan (Sonoya Mizuno), whose boyfriend, Sergei (Karl Glusman), a brilliant AI developer, dies in mysterious circumstances after he is invited to join the secretive 'Devs' division of Amaya, the computing company they both work for, run by mysterious billionaire CEO Forest (Nick Offerman).

Lily is shown shocking CCTV footage of her boyfriend self-immolating at the feet of a huge commemorative statue of Forest's dead daughter, Amaya, who was killed in a car crash, which towers over the tech firm's campus. But Lily does not believe Sergei would have taken his own life and, after finding something strange on his phone, she enlists the help of ex-boyfriend, Jamie (Jin Ha), to help investigate Sergei's death. All roads lead back to the Devs lab, a shimmering golden box enclosing a vacuum-sealed quantum supercomputer, which Forest and his team of engineers and physicists are using to explore something of immense consequence for humankind.

The $60million series explores themes of free will and determinism, as well as Silicon Valley's big-tech culture. Along with Spielberg's words of approval, Devs received a glut of rave reviews, with critics around the world praising its imagination, acting and soundtrack, together with the gloriously handsome spectacle of its immersive, emotional, elegant and chilling visuals. One even thought Devs to be worth watching twice.

Cinematography on the series was overseen by British cinematographer Rob Hardy BSC, who had worked with Garland on three previous occasions - the feature films Ex Machina (2014) and Annihilation (2018), plus a super-low-fi music video for English electronic band Beak, entitled "When We Fall II", featuring Mizuno coming in and out of shot. Hardy's other longform narrative credits include John Crowley's Boy A (2007), Red Riding: The Year Of Our Lord 1974 (2009, dir. Julian Jarrold), Broken (2012, dir. Rufus Norris), The Invisible Woman (2013, dir. Ralph Feinnes) and Mission: Impossible - Fallout (2018). Devs represents Hardy's first work on a TV series.

After six-months of prep, principal photography took place over 100 shooting days, split between distinct US and UK legs of production. Filming began in August 2018 with a two-month stint, taking in urban and woodland locations around Santa Cruz, California, including the city's university campus, as well as the conurbation of San Francisco and its famous landmarks.

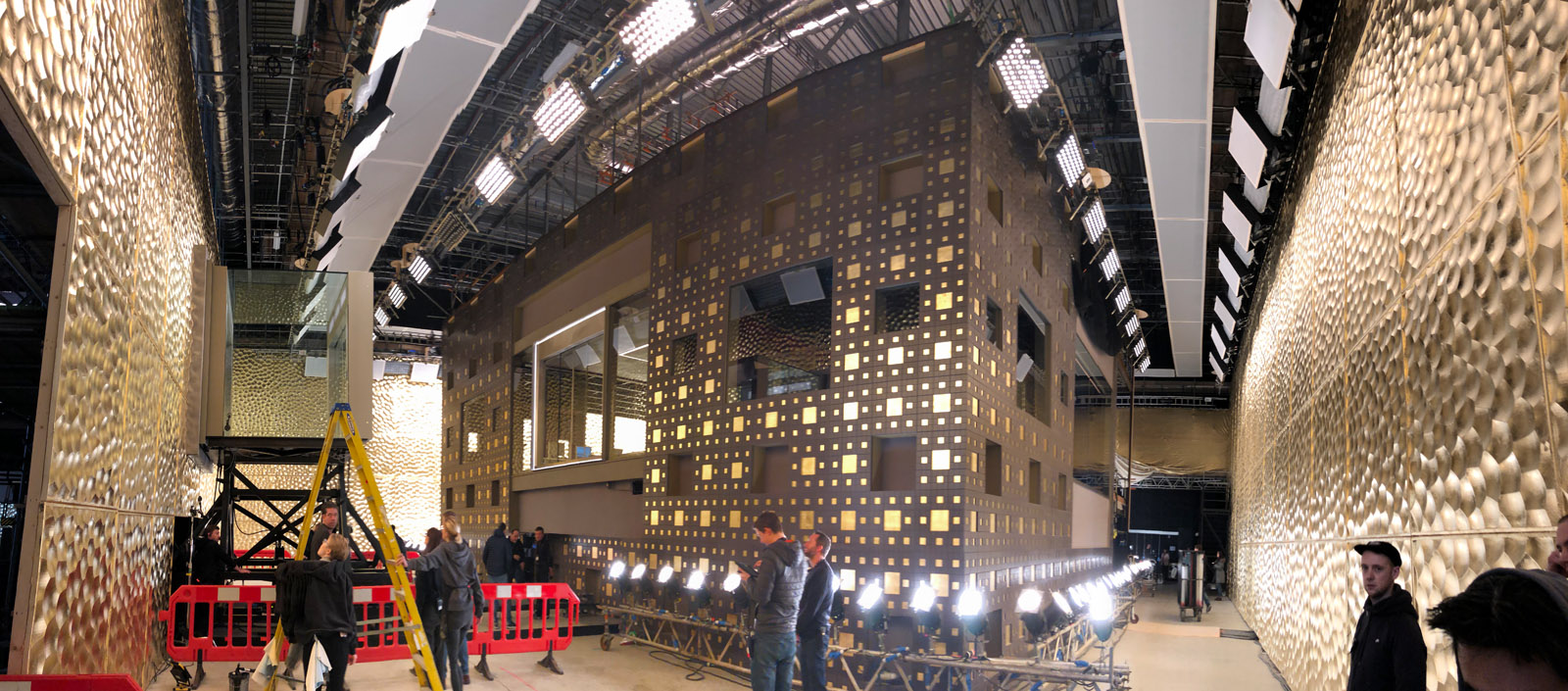

After a week's hiatus, production then resumed at Ealing Studios, UK, running between October and December, where sets for Lily and Jamie's apartments had been constructed. After a break for Christmas, the production team moved for a six-week stint at Space Studios in Manchester, where the voluminous Devs quantum-computing centre - the vacuum-sealed cube within a glimmering gilded cube - had been built. Production also encompassed The Lake District, and, later, a few additional days of aerial work of San Francisco.

"Shooting the Devs computing centre was the longest I have ever worked on the same set," says Hardy, "and a key challenge was to keep the imagemaking alive and interesting, without repetitions over such a prolonged period of time."

Ron Prince caught up with Hardy over Skype, as the cinematographer hunkered down with his young family in Atlanta after prep on his latest production, Sony's dark comedy thriller The Man From Toronto, starring Woody Harrelson and Kevin Hart, had ceased due to Covid-19 pandemic lockdown, along with all other US shoots.

Tell us about your working relationship with Alex Garland?

RH: You're part of a collaborative family. Alex has a great degree of loyalty towards his collaborators and has a tendency to work with many of the same people in key departments on his productions - like production designer, Mark Digby; set decorator, Michelle Day; VFX supervisor, Andrew Whitehurst; colourist Asa Shoul; and, of course, myself and my camera team. We had all worked together before.

Alex's scripts are always beautiful, intelligent and perfectly economical, with literally no fat, which is extraordinary. The quality of work is always outstanding and he instills great camaraderie. We have all built up excellent working relationships during the course of our work together. Prep is always thorough, with lots of roundtable meetings where everyone gets invited. During prep, I was always involved in meetings about storyboards, production logistics, costume, set design and construction, and so on.

When did you first hear about the script, and what were your thoughts about it?

RH: Alex started talking about a story idea, an hallucinogenic thriller set in a tech company, shortly after we had wrapped on Annihilation, although he was also looking at other projects at the time.

A while later he sent me the script for the first episode of Devs whilst I was still in production on Mission: Impossible - Fallout. It was instantly brilliant: compelling, concise, easy-to-read and extremely visual, but without being descriptively so. You can picture what he intends, but are not told how to picture it. He sent me the scripts for the next episodes as he wrote them. I don't think the script change at all from that time until we shot.

"For Alex, Devs was a one-off, a complete story in itself, and he was not interested in multiple series. It was never set-up as a pilot, as a single, initial teaser episode would have been neither practical nor affordable. It was all or nothing for him."

- ROB HARDY BSC

What were your conversations about the look of Devs? And what creative references did you consider?

RH: Many people use references as a shortcut to create a language between collaborators. But Alex and I don't find that necessary. Having worked together so closely and successfully before, I just know how he wants it to look, he knows how I want it to look, and we essentially just get on with it.

Our aesthetic conversations were predominantly with Mark and Michelle about defining what the Devs complex actually looked like, how it transforms and changes. But these were all on-going discussions about evolving the aesthetic in tune with the storytelling, rather having a particular hook to hang the visuals on.

Tell us about your selection of camera, lenses and aspect ratio?

RH: We shot Devs at 6K using the Sony Venice large format camera, in 2:1 aspect ratio, using specially-expanded Panavision C-series and E-series Anamorphic lenses. I also used a set of wide-angle Panavision H-series sphericals, as they were the only way to take in the expansive shots we wanted of the Devs complex that we shot at Space Studios.

I assessed all of the large-format camera systems that were available then. Beyond all of the technical analysis, we watched a blind splitscreen of the test material, and went with Sony Venice, as it was the one we liked looking at most.

On an aesthetic level, the sensor in the Venice is very sharp, which means it reads lenses well - the colours, contrast and light all roll smoothly together - and I knew it would get the most out of my choice of glass. Also, to my eye, there's a sweet spot when you shoot with the Venice at 2500ISO, but rated at 1250ISO, that gives rich blacks and highlights that round-off beautifully, with no granular artifacts. Essentially, you get a nice solid image from the Venice.

On a practical level, it is very set-friendly and simple-to-operate, and I knew the detachable sensor in Rialto mode would be very useful for the type of camera movement we were planning.

How about the 'specially-expanded' Anamorphic lenses you used?

RH: We wanted Devs to look elegant, and the C- and E-series Anamorphics - which I used on Mission: Impossible - Fallout - have a beautiful, classic and elegant filmic look about them.

We considered shooting in 16:9, but ended up shooing in 2:1, as the slightly wider field-of-view would work well for our amazing sets, but without ever feeling overtly self-conscious - as it would have, had we chosen 2.40:1 for the small screen.

However, when you shoot straight Anamorphic in 2:1 the aberrations around the edge get amplified. Whilst the image looks lovely, some of the drop off can also look like a mistake. Dan Sasaki at Panavision, Woodland Hills, expanded the lenses so the aberrations were pushed more to the edges of the frame. This dissipated any visual distractions, whilst intensifying the fall-off yet still retaining the Anamorphic visual signature. In effect a 40mm lens became closer to a 50mm.

Dan also introduced me to the vintage H-series sphericals, which I needed for wides of the Devs building. These were originally developed in the 1950s and have a beautiful three-dimensional quality about them. During the 1960s, the same glass was Anamorphicised to become the C-series lenses we know and love.

After principal photography wrapped, production went back to San Francisco to shoot aerials, and some run-and-gun on-street GVs, using the H-series lenses in combination with a Sony A7s MkII.

Did you apply any LUTs during the shoot?

RH: Yes, but I wanted to avoid having a patchwork of different looks, and to deliver visual consistency throughout the series. So I just used slightly-tweaked versions of my standard day and night LUTs, plus one for the Devs complex. I worked on these early-on during prep with my DIT, Jay Patel, and colourist, Asa Shoul.

Did you use any filtration on the camera?

RH: Just a little Tiffen ProMist diffusion, sometimes to aid the way the light behaved on certain shots, or where I wanted to mitigate a highlight, lower the contrast and soften the picture. However, I did use the amazing range of internal NDs in the Sony Venice. These are very useful as they eliminate the seesaw game you can get into with other cameras of attaching NDs between lenses.

Who were your crew?

RH: Devs was a two-camera shoot in the main, except for the scenes we shot at Space Studios of the Devs supercomputer complex, when we frequently had a third camera. I operated A-camera, with Julian Morson on B-camera for most of the shoot. However, when Julian had to leave for another project, we had several different operators covering B- and C-cameras, including Fionn Comerford, Rick Woollard, Catherine Derry and Ula Pontikos BSC. Grant Adams shot B-camera for us in the US. My long-term collaborator, Jennie Paddon, was first AC during the UK stretch.

My gaffer in the US was Todd Heater, with Lee Walters (who also worked with me on Ex Machina) in charge of lighting on the UK leg. Dave Childers was key grip in the US, with Sam Phillips the key grip in the UK. I was incredibly lucky to have had such a brilliant A-list crew.

How did you decide to motivate the camera?

RH: We wanted to shoot in a way that felt inexorable, mirroring the storyline of determinism, the inevitability of things, and, of course, to create a sense of relentless tension. Alex and I decided the camera would never stop moving, although some of those moves were very subtle and you are barely conscious of them. During the US leg, we used cranes and the dolly to motivate the camera.

However, for the scenes in the Devs building we needed a different approach, as we sometimes had seven or eight pages of dialogue to cover, and wanted to shoot these in elegant, continuous takes.

Also, because we would be shooting on that set for six weeks, we wanted to keep things visually interesting, using evolving moves around the actors, and compositions developing into other compositions - all whilst making the most of the horizontals, verticals and reflections in the set design, and all without repetition.

We needed full control to do that. Steadicam just did not feel like the right option, and some of the choreographed moves we were planning would have been too difficult or impossible to operate in a traditional way off the dolly.

So I re-explored the StabilEye system, developed by Dave Freeth and Paul Legall, which we had used previously on Annihilation and Mission: Impossible, for its handheld potential.

Up to that point, StabilEye had only been engineered to mount Red and Alexa cameras. But I requested them to quickly adapt it to take the Sony Venice sensor block. During production, the sensor block was mounted on StabilEye and tethered to the camera body via Sony's Rialto Camera Extension System. We mounted the camera body to the dolly as a transport mechanism.

All-of-a sudden, we had StabilEye working as a remote, stabilised head in the hands of our grips. I remember Dave Freeth being excited that was a first with his kit. He customised the software to accommodate our very precise and subtle compositional shifts during these long takes.

With this in mind, we had the floor of the Devs set built so that it was smooth to enable the dolly and the grip to dance floor over the surface. During production, I operated the wheels and viewed the camera output remotely, whilst being on comms to Sam Phillips, my key grip, who handled StabilEye on-set.

Very quietly, I talked him through a move, so he could slowly jib up/down, or move-in for a specific moment, reacting to whatever the actors were doing. It proved a great way to work, and gave us a variety of shots we could not have achieved otherwise. We were very much improvising, and it enabled us to work instinctively.

The lighting inside the Devs building is particularly spectacular. How did you create that?

RH: Working with Lee Walters and the set designers, the lighting was predicated around being able to move the camera 360-degrees around the set, and to shoot in different rooms - essentially to put camera anywhere and to control how the space looked.

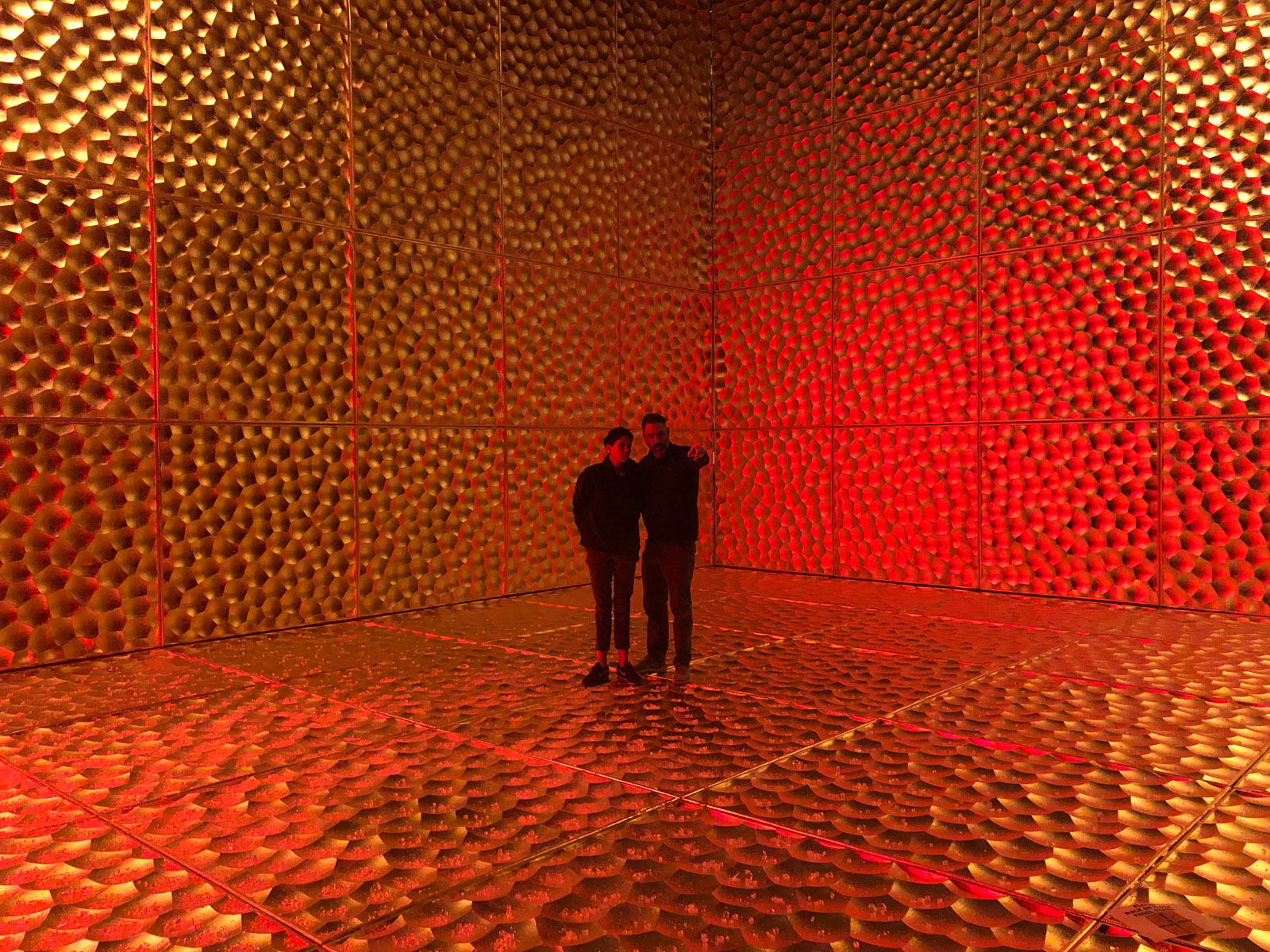

So the whole construction - the cube within a cube - was conceived as a contained set with integral lighting. The inside walls of the outer cube were lined by 4 x 4ft golden tiles, some in gold leaf, with a dimpled surface that reacted to changes of light and light direction.

A key conversation Alex and I had about the Devs cube was that it should feel beautifully elegant and lit predominantly with reflected light. We had a huge number of Tungsten Nine-lights around the entire top of the cube, plus tracers, par cans and additional Nine-lights at the bottom to create waves and pulses of light across the tiles. We could change the chase patterns of the lights in seconds. The effect looked spectacular and the reflected light was beautiful. For six weeks not a single floor lamp was used on-set.

The room with the gold hexagonal table, in which the Devs team undertake their experiments, was built floor-to-ceiling from glass, with a layer of diffusion over the surface, and over 1,000m of LED ribbon behind the diffused layer. We could change the colour of the room from white to block colours, like red, green and blue. The green looked particularly impressive, and we had a lot of fun with that.

Tell us about the DI grade:

RH: I did the final colour grade with Asa Shoul at De Lane Lea in Dean Street, Soho, part of Warner Bros'. post-production facilities. He is a true artist and has been a regular collaborator since The Invisible Woman.

We graded Devs episode-by-episode, with completed VFX scenes coming in all of the time, and gradually locked each of them down, before doing one last pass over the whole series.

We graded in 4K HDR, and the did the SDR pass after that. Working in HDR was extraordinary. It's almost three-dimensional. You see details in the HDR image - the skies, low-lights and shadows - that you would not normally pick up on in SDR. It's not sharpness, just detail. The aerial and landscape shots, such as those above San Francisco and those in the Lake District, look incredible.

Your final thoughts on shooting Devs?

RH: It was rich and rewarding experience to work with Alex again, but it was a marathon not a sprint. Perhaps the toughest thing was working on the same stage for such a prolonged amount of time, and keeping the pictures alive and interesting. We had to remain focussed and engaged with the process, and hopefully our devotion to that will mean audiences are engaged with the story too.

All images courtesy/copyright of FX Networks, LLC. All rights reserved.