The Right Amount Of Grain

Across the Pond / Mark London Williams

The Right Amount Of Grain

Across the Pond / Mark London Williams

In a lively period where the very deadlines for this column were strained nearly to capacity, we bracketed our month with visits to the former Eastman Kodak Building, now occupied by the “Sim Group” of Studios, Camera, Lighting & Grip, and Post Services, but which has coalesced under a single, branded banner.

The rebranding event took place sequentially at their various facilities, including Vancouver, Atlanta, NY, and the Toronto mothership. But they started in Los Angeles, where they occupy that aforementioned emulsion-era Kodak building in Hollywood. Which Chief Business Development Officer Chris Parker recently joked is now referred to as “the codec building.”

We shall return to the journey from Kodak-to-codec, but our peregrinations also include not only an Emmy dinner, but talks with two more DPs, both among our “Likelies” in the current award conversations.

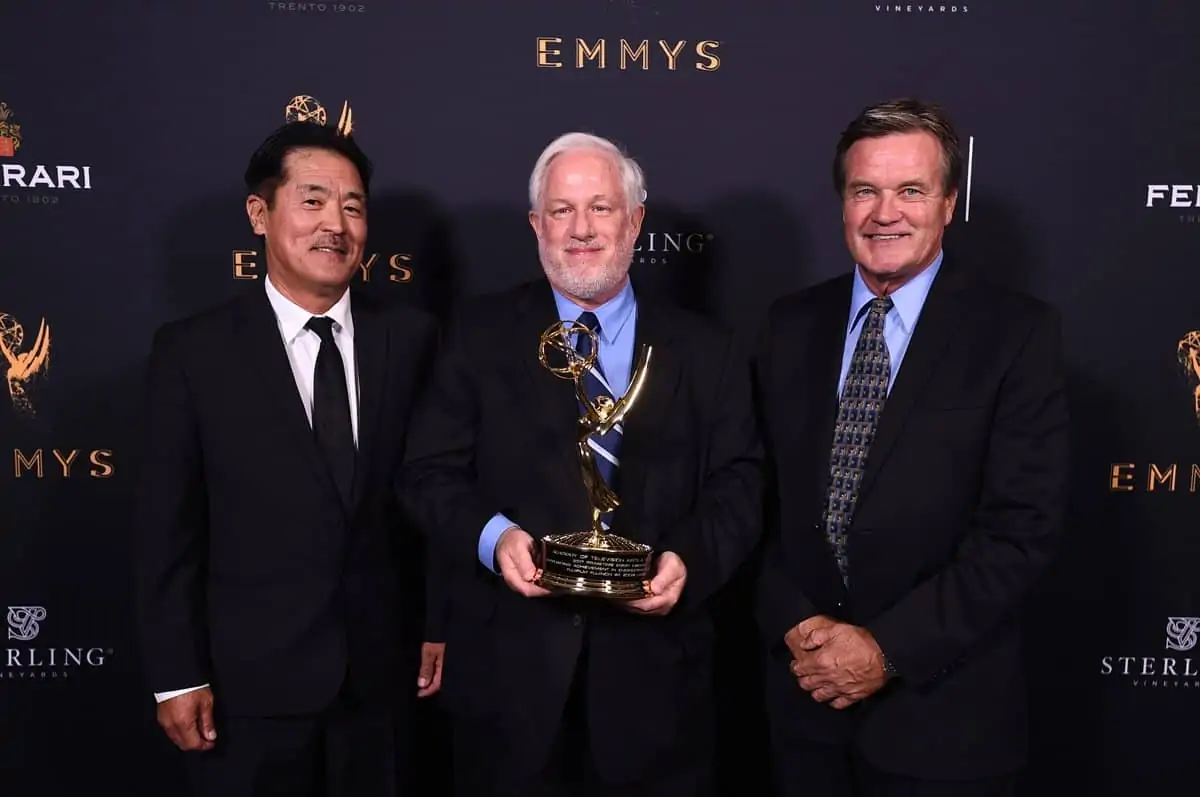

The dinner was held a few nights before Halloween, with most of L.A. gripped by another extra inning game in a World Series that would eventually break its heart. At the Loews Hollywood Hotel, however, in the very ballroom that serves as the “backstage” press room on Oscar night, the Emmys were wrapping up business in an evening akin to the Oscar’s Sci Tech Awards, celebrating inventive breakthroughs and significant additions to the toolbox, or as the official release states, “honoring an individual, company or organization for developments in broadcast technology.”

And here we pause to consider that not only does broadcast now mean “streaming” a good deal of the time, but a lot of the gear honored on the TV side is often indistinguishable from what feature “films” use - the very stuff that will be also be honored when Loews converts back to Oscar use.

Also like the Sci Tech dinner, the 69th Engineering Emmy Awards were a relaxed affair, since everyone knew in advance they’d be honored. No chance of a Moonlight / LA LA Land moment, even if Canon and Fujinon were both feted for their versions of the same breakthrough: “Each independently developed 4K field production zoom lenses for large sensor or super 35mm cameras providing imagery in television that could only be accomplished previously by prime lenses.”

Another honoree on the camera side was ARRI, spotlit for their Alexa camera system, which “along with its completely integrated post-production workflow, represent dynamic and transformative television technology,” as the TV Academy put it, which echoed what the Arri team said when they went to accept their award: They “envisioned a camera for a new golden age of television.”

One of the more humorous highlights was the pause for the evening’s own “Memoriam Reel, as the video noted the passing of now-jurassic technology such as Betamax, lens turrets, 3-D TV, Ampex tape, and others.

One thing not in that particular scrapheap of history though would be “old lenses,” since that glass, as our regular readers know, is constantly being “rehoused” for use in this brave new digital world.

But of course there is “new glass,” too, and that’s what Canon and Fujinon were being honored for, with their 4K breakthroughs.

Canon Senior Fellow Larry Thorpe showed clips from the BBC’s Planet Earth II, which splendidly showed what Canon’s “field” lenses can do (hooked up in this case to a RED Dragon). The honors included the company’s CN-E, CINE-SERVO and COMPACT-SERVO lines of zoom lenses, and Canon’s Exec VP, Elliot Peck, added some erudtion to the evening - or more eruditon, aside from the quips of the evening’s host, actress/playwright Kirsten Vangsness - noting that the philosopher Baruch Spinoza’s “day job” had been to... grind lenses.

Of course, when he wasn’t contemplating glass, Spinoza was saying things like “the highest activity a human being can attain is learning for understanding, because to understand is to be free.” And certainly, as more is understood about digital production, the increasing possibilities of what and where things can be filmed, frees up, as the Planet Earth series showed.

There were several “non-visual” honorees as well, including Disney for a system that allows for easier creation of foreign language dubs for shows and Shotgun Software for helping streamline production and workflow.

But as noted, the “freeing” aspects of that workflow is scarcely the exclusive province of small screens. DP Rachel Morrison used some of those honored ALEXAs, in this case a couple of Minis, to shoot the feature Mudbound, with director Dee Williams.

The film tells the tale of two PTSD-stricken GI’s returning to their rural Mississippi home after World War II. In their pain, they find a bond, but greater pain follows since one of the friends is white, and the other black.

"Just the right amount of “grain” is now one of the grails in the digital era... and also just one of the many things being done in the offices, editing bays and facilities at the Sim building."

- Mark London Williams

The film itself straddles those platform boundaries showing that what the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences honors, vs. what the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences does, is increasingly overlapping.

Mudbound will get a theatrical release, for Oscar consideration, in addition to its upcoming “airing” on Netflix. Morrison recently wrapped Black Panther for director Ryan Coogler, with whom she collaborated on Fruitvale Station, and has gone to shoot both fiction and “non,” garnering an Emmy nomination for her additional cinematography on Netflix’s What Happened, Miss Simone?, with a few outings for Oprah Winfrey’s Master Class.

She wanted the fictional Mudbound to look more documentary-like, however, citing the famous work of “New Deal”-era photographers Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans as influences.

Morrison assumed she’d recreate the same visual language by shooting “on film - I couldn’t imagine any other way.” Though the additional cost would’ve meant only 26 days of production time, instead of the already jam-packed 28 they wound up with. “As soon as film was taken off the table,” she said, “it really became about the ways to make the digital seem tactile, feel humane.”

That was done by putting “old glass” on the two Minis used to shoot in the film’s close-quarters: All real farms and plantation houses (though in Louisiana instead of Mississippi).

That glass was primarily rehoused Panavision Ultra Speed Prime Lenses. “For scenes that were dependent on firelight, I ended up using spherical lenses,” she said, which were a “mixture of uncoated super speeds and medium speeds.”

After shooting at a high enough ASA to introduce some grain in the images, she added more in the DI, to bring the digits not only closer to film, but to the work of Lange, Evans, and the colors of Gordon Parks, whose photography she also referenced.

Recapturing, or at least distilling, the past was also cinematographer Ed Lachman’s job in his latest collaboration with director Todd Haynes, in the visually wonderful Wonderstruck, which adapts Brian Selznick’s primarily visual book, and follows the ultimately intertwining stories of two deaf children, one in the 1920s, the other in the ‘70s.

The film is visually multilayered, with the ‘20s sections playing as a “silent movie,” replete with subtitles, and films-within-films, as Rose, the girl from this segment - played by a marvelous Millicent Simmonds - also watches silent movies on screen, done in a D.W. Griffith-esque style distinct from the “wrapping” narrative.

All of which is, in turn, intertwined with the ‘70s story, for which Lachman told us, he consulted Owen Roizman, of French Connection, Three Days of the Condor, and other midcentury fames, along with looking at Kent Wakeford’s work in Scorsese’s Mean Streets. “I try to use tools of the era,” he told us, which meant Panchro lenses, Western dollies with pneumatic wheels to mimic camera moves, and “zooms as visual punctuation” for the later sequences.

His research even found that with certain zoom lenses, like those from Angenieux, “there was more lead in the glass” in those gritty Eastman Color-era movies (well, heck, there was more in the gasoline, too). To get some of that same grit, Lachman said he “pushed modern day film a stop,” for more grain.

And if just the right amount of “grain” is now one of the grails in the digital era, it is also just one of the many things being done in the warren of offices, editing bays and facilities at the aforementioned Sim building, where we came in this month.

On their rebranding night, CEO James Haggarty mentioned the separate former brands under the company’s purview - Tattersall Sound, Pixel Underground, Bling Digital Dailies, and more - that were now all coalescing under Sim’s one-stop banner, as they endeavor to offer not only all the gear on the rental side, but the various solutions for workflow on the finishing, or “post” side. Though as Bling’s founder Parker pointed out - the very one who is now Sim’s BDO - when we returned for our follow-up visit: “the line between production and post is blurred,” and only getting more so.

We walked around the former Kodak building, where now shows like Game of Thrones are now colorized, which was left with only its history, its outer four walls, and the inside stair cases, before Sim moved in with a complete overhaul that includes everything from a 4K DI theater to a sound room with a live feed to the company’s larger mixing room in Toronto, for concurrent mixing sessions, to rooms where “a DP can shoot a test and walk up to a color bay and send out footage.”

Once, that would’ve literally meant literally “send.” Now it can mean a connection to Malta, Morocco, or some other tax-incentivized locale, via the 170 miles of cable that Sim installed throughout the building.

“We look for adequate, local bandwidth,” Parker told us, when planning real-time workflows with remote productions.

But it’s an era where everyone’s “bandwidth” needs to remain open enough to encompass changes coming far faster than they did in the era of Mr. Eastman.

It’s just too bad he never picked up his honorary Oscar or Emmy.

We’ll see you next time, even deeper into the holidays.

Meanwhile, write us: AcrossthePondBC@gmail.com