GOLDEN EYES

Clapperboard / Phil Méheux BSC

Golden Eyes

Clapperboard / Phil Méheux BSC

BY: Ron Prince

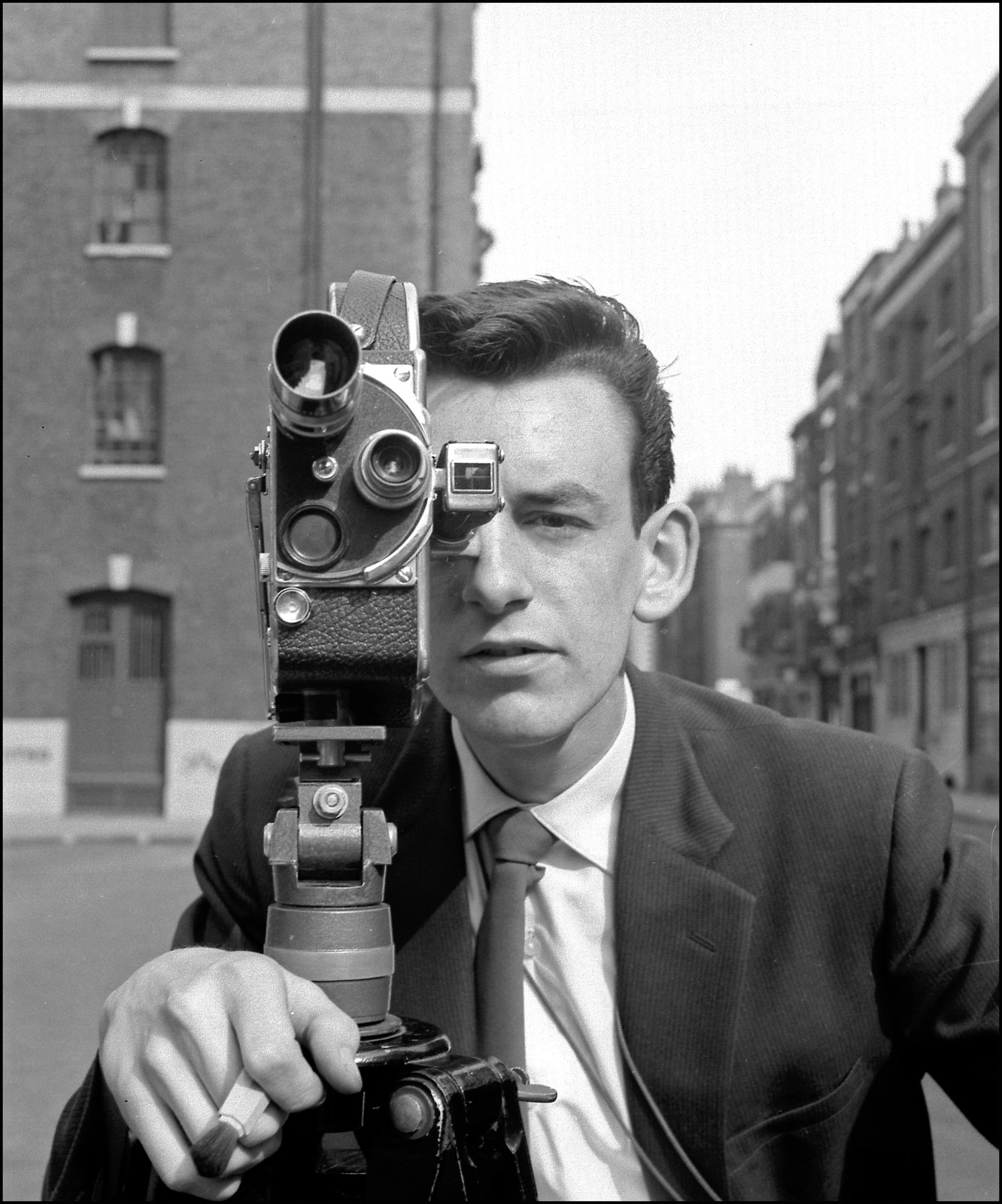

Offering an imaginative and intelligent approach to cinematography, award-winning DP Phil Méheux BSC has enjoyed a stellar filmmaking career spanning the best part of six decades.

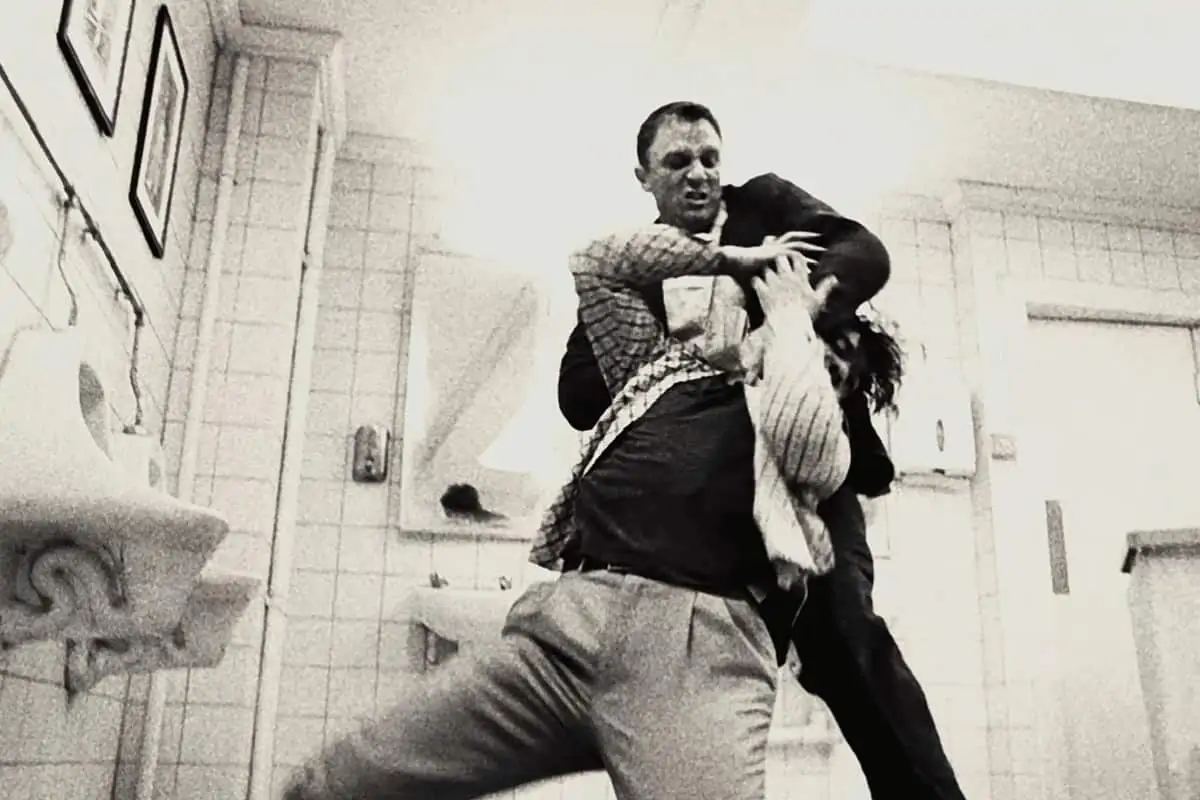

Continually sought-after, his outstanding photographic talents led to collaborations with renowned directors and resulted in him shooting a range of critically-acclaimed and bankable features - including The Long Good Friday (1980), The Mask Of Zorro (1998), Entrapment (1999) and two 007 James Bond pictures - Goldeneye (1995) and Casino Royale (2006). The latter of these successfully rebooted the franchise in adrenalised, action-packed style, with Daniel Craig entering the fray as a meaner, moodier version of the famous super-spy, earning a BAFTA Nomination and the BSC Best Cinematography award.

Méheux's star is such that he served as president of the BSC from 2002 to 2006, and was honoured with the prestigious International Award from the American Society of Cinematographers in 2015, "reserved for cinematographers of international repute who have made extraordinary contributions to the art form."

Méheux was born in 1941, in Sidcup, Kent, during the height of the WWII blitz. He says that his interest in visual media began before he was even five years of age. He recalls his grandmother taking him and his older brother on an excursion to Wembley Ice Rink to enjoy the Christmas 'Pantomime On Ice', but remembers being more fascinated by the spotlight operators following the skaters and the "dubbing box" from which singers and the orchestra added voices and music, than the actual show.

He also recollects weekly visits to the local cinema, especially the viewing experience of Walt Disney's animated classic Bambi (1942), at the age of seven, being completely captivated by the colourful images projected on the big screen and the emotions they created.

Growing older, he became besotted with films and filmmaking, poring over magazines and books with illustrations of studios at work and behind-the-scenes articles. From as early as age ten, he says, "I knew I wanted to be the man who sat on the camera crane as it swooped over marching soldiers or costumed extras," and he spent many happy times in the family garden re-enacting scenes with cardboard models of cameras.

The young Méheux also saved enough pocket money to buy a hand-cranked 9.5mm projector and rented newsreels and two-reel comedies from a local photographic shop, which he projected on the wall of the family domicile. During his early teens, he also taught himself to take, process and print still photographs - ranging from countryside scenes to people on the street and objects in his parent's home.

"That's when I learned what happens if you under or overexpose film and change the development process," he says. "I also learned about resolution and grain, how to compose images and find the right light for different photographs. I remember once waiting for over an hour, for the sun to set for just above a line of trees, to get the perfect shot."

Leaving school just before his 16th birthday, with five O-levels to his credit, he had the fortitude to decline a job offered by the careers adviser as a shipping clerk at London Docks, preferring to stay true to his own ambitions. As luck would have it, sitting one afternoon in a Lyons Corner House near Charing Cross railway station, he spotted a recruitment ad in the London Evening news for a promising-looking opportunity - in the sales department of MGM Film Distributors, St James Street. The fledgling film fanatic got the job as a clerk (grade three), paying £3.10s a week.

Méheux quickly made friends with other teenage film enthusiasts at the company, and their mutual interest in home cinema led them to pool their finances to towards the purchase of two 16mm sound projectors. On most Sundays, they could be found with the curtains drawn watching rented feature-length movies - from Singin' In The Rain (1952, DP Harold Rosson ASC) to The Seven Samurai (1954, DP Asakazu Nakai) - complete with reel changeovers.

"I believe the BSC and other cinematography organisations have a responsibility to help everyone understand that people working together is what makes filmmaking an art. We should be making the decisions about how to produce our films not always being led by economics and the latest invention."

- Phil Méheux BSC

That experience motivated them to try their hand at creating their own stories on film. Calling themselves Studio 16, and buying a second-hand 16mm Bolex camera, their first collaboration, with Méheux designated as the camera operator, was a short documentary based on classical composer, Malcolm Arnold's 'The London Fantasia' about London's regeneration after World War II.

"I learned so much about composition, camera angles, double exposures and editing, as well as other tricks of the trade, by making amateur films for Studio 16," says Méheux. "We had no access to sound equipment, so we learned to tell stories with pictures. Films like Black Narcissus (1947, DP Jack Cardiff OBE BSC), The Red Shoes (1948, DP Jack Cardiff OBE BSC) and Lawrence Of Arabia (1962, DP Freddie Young OBE BSC) and are good examples of films that did wonderful jobs of telling stories with images that evoke emotional responses."

Méheux's second job, aged 18, was as a projectionist and librarian at a London advertising agency who made commercials. The firm had a small screening room and editing equipment. When the staff went home, Méheux and his friends would often gather in the screening room to watch other people's films or see art house films - such as John Cassavetes low-budget 16mm Shadows (1959, DP Erich Kullmar).

Encouraged by the success of that film, Méheux and his friends developed a script for a feature film to be shot in a similar manner and set about trying to get it going. They found two potential backers and ultimately gave up their regular jobs to concentrate fully on the project. Unfortunately, however, as often happens, the backers dropped out at the last minute and, in 1962, Méheux found himself working as a projectionist for the now defunct Cameo Royal Cinema, Charing Cross Road.

Fortunately, an usherette friend pointed out an advertisement in the Sunday Times for a 'trainee assistant film cameramen' at the BBC. Although Méheux discovered the training course was full, his skills earned him the role of studio projectionist. His desire to get behind the camera was not long unrequited, and in 1964 he began a traineeship in the camera department at BBC Television Film Studios at Ealing. He became an assistant and ultimately a documentary cameraman.

"The great thing about documentaries is that they teach you to be ready for anything," he says. "I learned to compose shots on the fly. I knew the editor was going to need cutaways and reverse shots. It was up to me to get them by being in the right places at the right times."

Méheux spent twelve years at the BBC, an experience he says was "priceless", travelling the world and assisting many different cameramen with many different styles, and working more and more in drama on BBC's Plays For Today (1975-77) series and even night action sequences for the popular police series Dixon Of Dock Green.

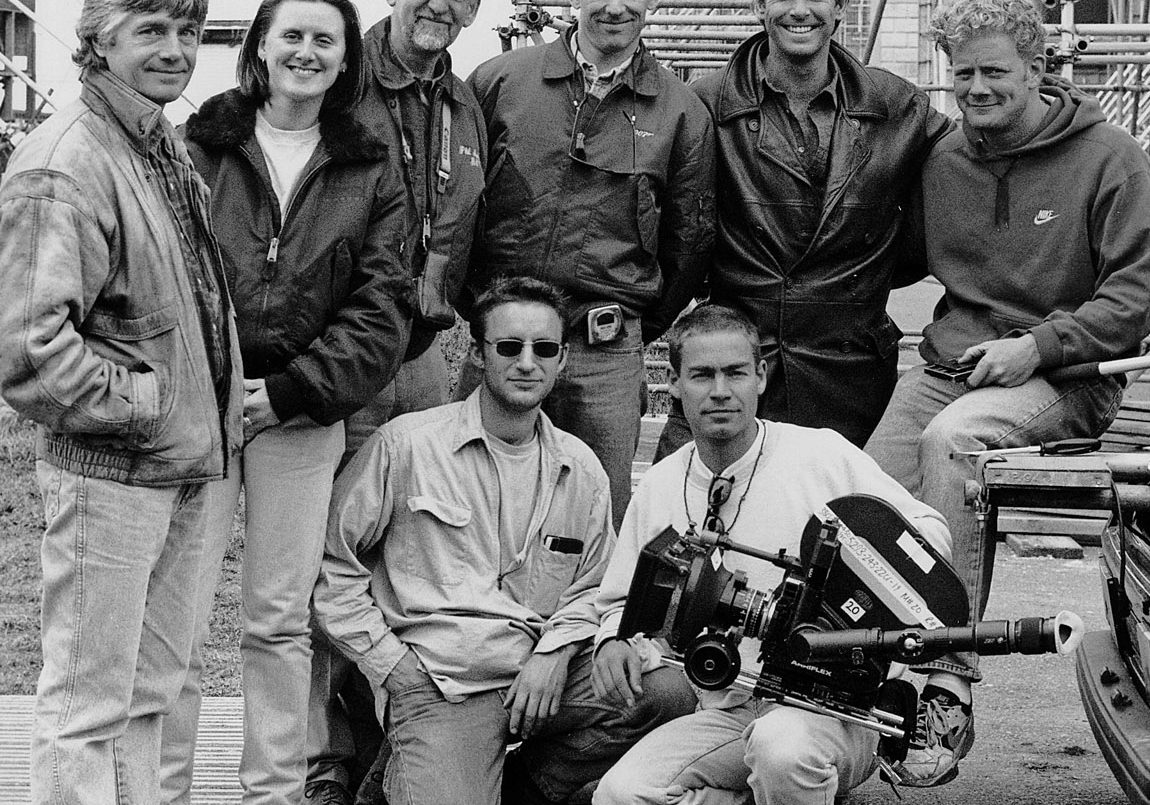

Having seen Méheux's TV work, Tony Simmons, a freelance director, persuaded him to be the cameraman/operator on Black Joy (1977), a low-budget feature requiring extensive use of documentary techniques. Although this meant him leaving the BBC, destiny was calling. The 35mm feature became the official British entry at Cannes Film Festival in 1977, and film's line producer Martin Campbell, was to have a definitive influence on Méheux's later career - the pair collaborated on 19 feature films together with Campbell as director, including both 007 films and the feature film version of Edge Of Darkness (2010).

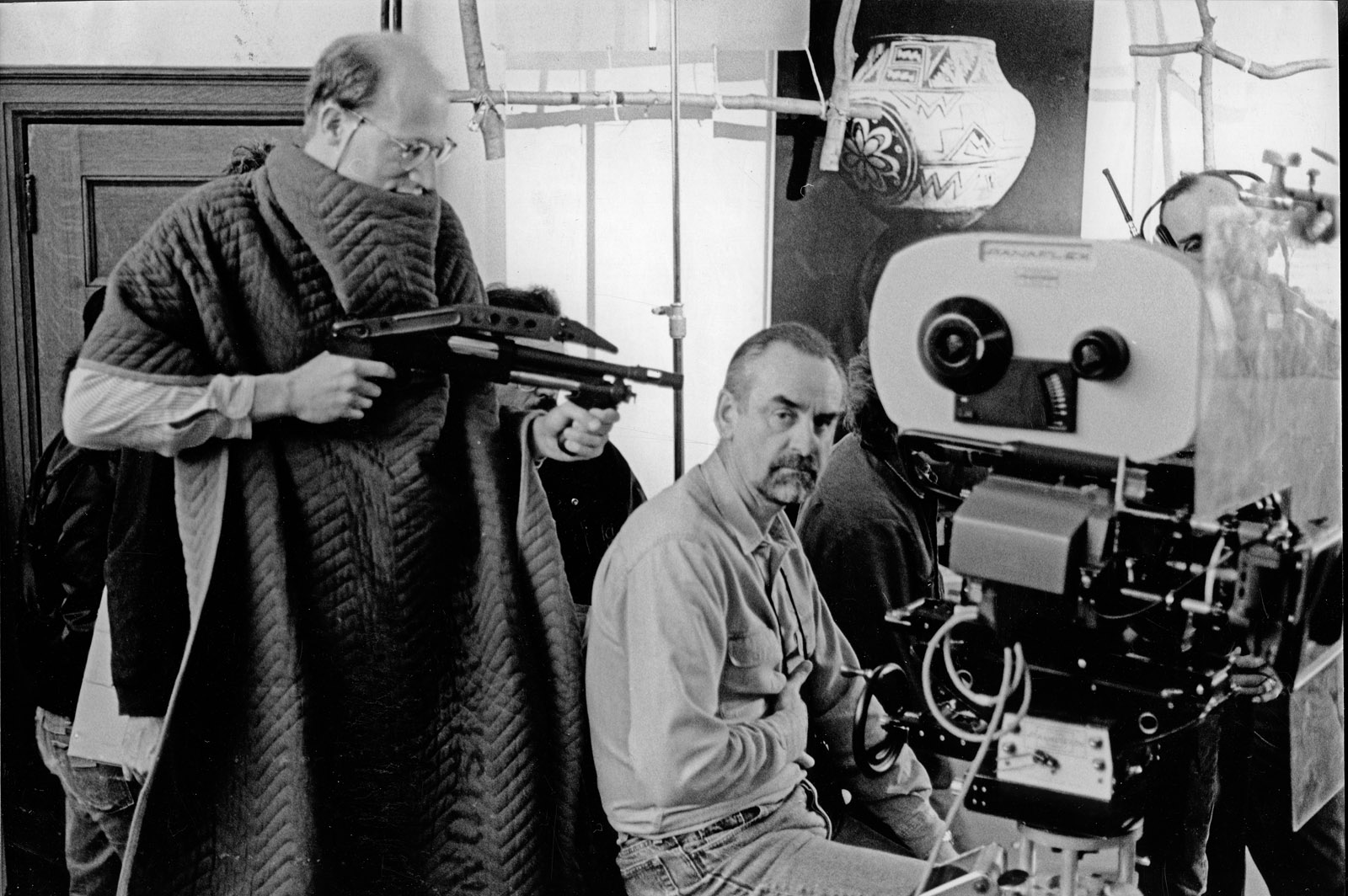

From here, Méheux carved an enviable reputation as one of the most versatile directors of photography. In the meteoric career that ensued, he collaborated with renowned directors on a variety of productions: Scum (1979, dir. Alan Clarke), The Fourth Protocol (dir. John Mackenzie. 1987), Max Headroom (1985, dirs. Annabel Jankel/Rocky Morton), Ruby (1992, dir. John Mackenzie), The Saint (1997, dir. Phillip Noyce), Bicentennial Man (1999, Chris Columbus). Méheux also explored new territory when he filmed Smurfs 1 & 2 (2011 and 2013) in 2D and 3D. He also shot countless TV and cinema commercials for the a wide variety of products, ranging from cars to food.

In 1979, Méheux was invited to full membership of the BSC and has been a board member since 1999. He was elected president in 2002 and served two terms in this position until 2006. He is also an elected member of the Academy Of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences and an honorary member of the Australian Cinematographers Society.

"We think of books, paintings, sculptures and things like that, which are created by one person, as art," Méheux says. "Filmmaking can be an art too, although it involves writers, directors, actors, music composers, cinematographers and other people collaborating together.

"I believe the BSC and other cinematography organisations have a responsibility to help everyone understand that people working together is what makes filmmaking an art. We should be making the decisions about how to produce our films not always being led by economics and the latest invention."

Méheux still lends his cinematic skills in mentorship of friends and aspirant filmmakers. He also often teaches and participates, as either a judge or speaker, at filmmaking events around the world. And, in keeping with his innate enthusiasm for all-things-cinematographic, he edits the BSC Newsletter, is shooting conversation pieces with leading BSC members, and is collaborating on book about BSC members past and present.

For those beginning their journey into the life cinematographic, Méheux advises, "Study the light around you, and how it affects the way you feel about what you are observing. Anyone can press a button and get an image with a digital camera, but is the light really telling the story? You need to be able to adapt and manipulate the light to tell that story.

"My lament is that reality TV produced stories and images that are not photographed, but captured. This is slowly permeating high-end TV and feature films, where there's a trend to shoot handheld in available light. To me that's not making films, that just capturing what's in front of you.

"What we need to hold on to is the ability to create imagery and tell stories with light and lenses, editing, costume and set design. I learnt my craft from a standing start, working my way through different roles. That was my university education. So along with your own craft, the more you can learn and understand about the roles of other people around you, the better filmmaker you will become."

So, is he about to retire? "Not yet," he laughs, "I'm available!"