SHOW TIME

Cinematographer Pat Scola’s Sing Sing employs Super 16mm film, vintage lenses, and natural light to authentically capture the emotional depths and stark realities of prison life.

“There’s a lot of sadness and hope,” cinematographer Pat Scola says about the prison-set drama Sing Sing. A phrase which might describe much of the world right now, but here applies to the inmates and characters in the award-buzzed film which shares its name with the titular prison in New York’s Hudson Valley. A prison – like most – where when “you’re in the same place for 20 years…nothing really changes.”

At least, not compared to what’s happening outside the prison walls. It was a concept Scola alighted on that “stemmed from a watch” one of Sing Sing’s inmates was wearing. “One guy wore a big fancy watch – but the time was always wrong.” Because the actual “outside” time didn’t matter.

It was one of the many insights into life in lock-up that Scola picked up while shooting the movie, which came together because of a previous project that he, and director/co-writer Greg Kwedar had been working on, that “ended up falling apart at the last minute.” In retrospect, Scola says, Kwedar and he “are glad it did.”

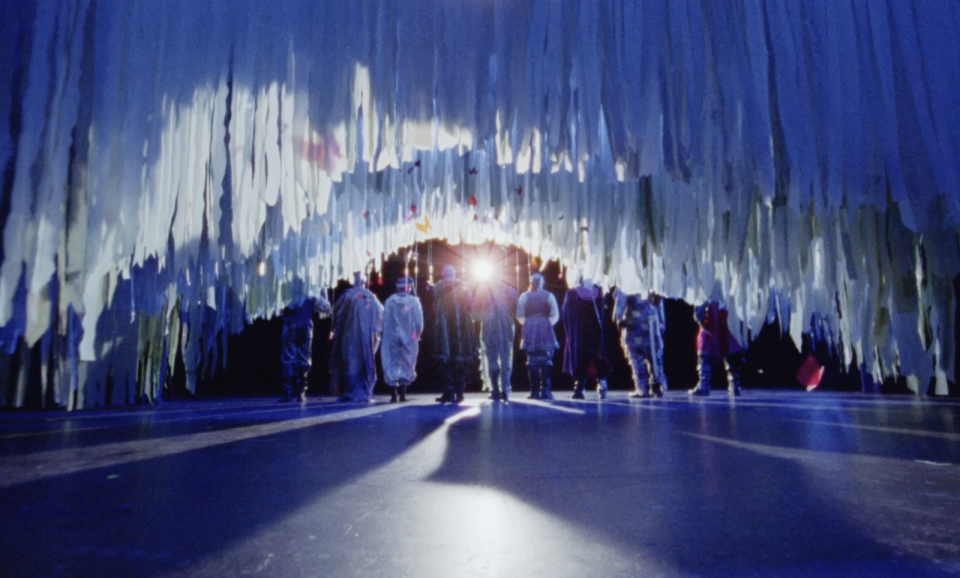

Kwedar wound up calling him to pitch the new project verbally. The script is based on books about, and stories by, former inmate John “Divine G” Whitfield, who helped oversee a theatre company in Sing Sing, part of New York’s still-remarkably-extant RTA programme, or Rehabilitation Through the Arts, which, as its mission statement declares, helps “develop critical life skills through the arts.” And if the film is anything to go by, some of those skills are astonishing indeed.

Whitfield – who was already performing and writing when jailed for a crime he didn’t commit – shares “story by” credit with Clarence “Divine Eye” Maclin, who was a fellow prisoner, and co-stars in the film with Colman Domingo, who also co-produced.

While it’s no surprise that Domingo’s performance, as Whitfield, is likely to be part of any handicapping for this year’s Oscars, Maclin, playing a version of himself – an inmate both intrigued by, and resistant to, what RTA offers – seems to have fully sprung into the supporting actor discussion as well.

And though the film isn’t set in the ‘70s, it plays like one of that era’s vital character studies, which legacy studios used to produce more regularly, before such terrain was ceded to companies like Sing Sing’s A24. Scola calls it “the kind of movie I got into making films for”.

To make it, he even chose a somewhat retro toolbox, driven not only by aesthetics, but other practicalities such as shooting in Super 16mm with both an Arriflex 416 and an SR3, with Zeiss Ultra 16s, noting that there isn’t “a whole tremendous selection of Super 16 lenses.” But, he adds that by “lean(ing) into much older glass – there’s a haziness to it. It has a texture of something that is not of today,” emphasising the different rhythms, or lack of rhythms, from being locked up. “You don’t know when (this) time is.” There was also a certain stillness to the focal length, with much of the film shot from 25mm.

The choices helped emphasise something Scola “found terrifying [when I was] scouting: the amount of windows in these places”. He considered that might have made things harder still for these men who “find themselves inside this oppressive place,” to glimpsing the world outside, while knowing how absolutely severed they were from it. This was especially profound in Sing Sing itself, located along the lush Hudson, and the very prison that prompted the American slang term about being “sent up the river.”

It is, however, quite a gorgeous river, so “you stand there, you look over the Hudson [and] that’s worse in some ways than the wire and everything else. That’s why we wound up using so much of the windows. As a result,” he says, “film became increasingly important there. Most digital sensors wouldn’t have been able to handle the highlights outside,” with that outside world “becoming an extension of the inside sets”.

He also found film “much more forgiving [when] using lots of untreated natural light and often shooting 360 degrees”. Ultimately, he felt the minimal use of lighting “helped the performances of a lot of our cast who were primarily used to acting on stage”.

Though the actual stage sequences, capturing dress rehearsals and performances, were filmed at New York’s Beacon High School, a college prep school in the Hell’s Kitchen area of Manhattan. “Obviously the theatre scenes had a bit more lighting, but we were clever in utilising a lot of what existed in the high school,” he says. “We even paid a high school theatre student to run their lighting board.”

It was another detail about the shoot that made it the “polar opposite” of the $100 million horror franchise prequel he did right after, marking what he notes has been “a busy two years for me,” which also included an Independent Spirit nomination for the Chicago-set We Grown Now.

“I’ve made movies that aren’t special, and I’ve made some that are,” he says, applauding A24 for “taking that risk,” on Sing Sing, something that wasn’t “just some bleak or artistic film,” but instead, for Scola and everyone involved, one clearly in that “special” category.