Pet Project

Nicolaj Brüel DFF / Dogman

Pet Project

Nicolaj Brüel DFF / Dogman

BY: Michael Burns

Dogman is the atmospheric and critically-acclaimed 2018 film by Gomorrah director Matteo Garrone, which manages to display both documentary grit and cinematic richness at the same time.

This is no small part due to the look and lighting created by Nicolaj Brüel DFF, who won the David Di Donatello award for best cinematography in 2019 for the film, among a profusion of other nominations and awards.

The story of how Marcello, a diminutive dog-groomer and small-time cocaine dealer, dances around the inhabitants, both canine and human, in a run-down Italian town, is told with both despair and humour by Garrone. However, working with the director was initially a step outside the comfort zone for Brüel, a Dane known for his lush commercials work.

"Matteo wanted the freedom to shoot at all angles at all times, which obviously is a huge challenge for a cinematographer," explains Brüel. "I think Matteo somehow feeds on the chaos: he likes to be unprepared and see what comes out of it. It has to be real and spontaneous. It gives him a lot of freedom to create, on the spot, in that very second. He likes to call positions, and just go for it. You put the camera on your shoulder, head to the location and off you go!

"Being Danish, I like to be well-organised and well-prepared, so it was very different," he continues. "It was quite frightening really, especially coming off commercials, which because of reasons of time and money are much more organised, and more prepared. Early on in the process, I realised that I had to treat this completely differently. I just had to let go of all the control and just go with the flow."

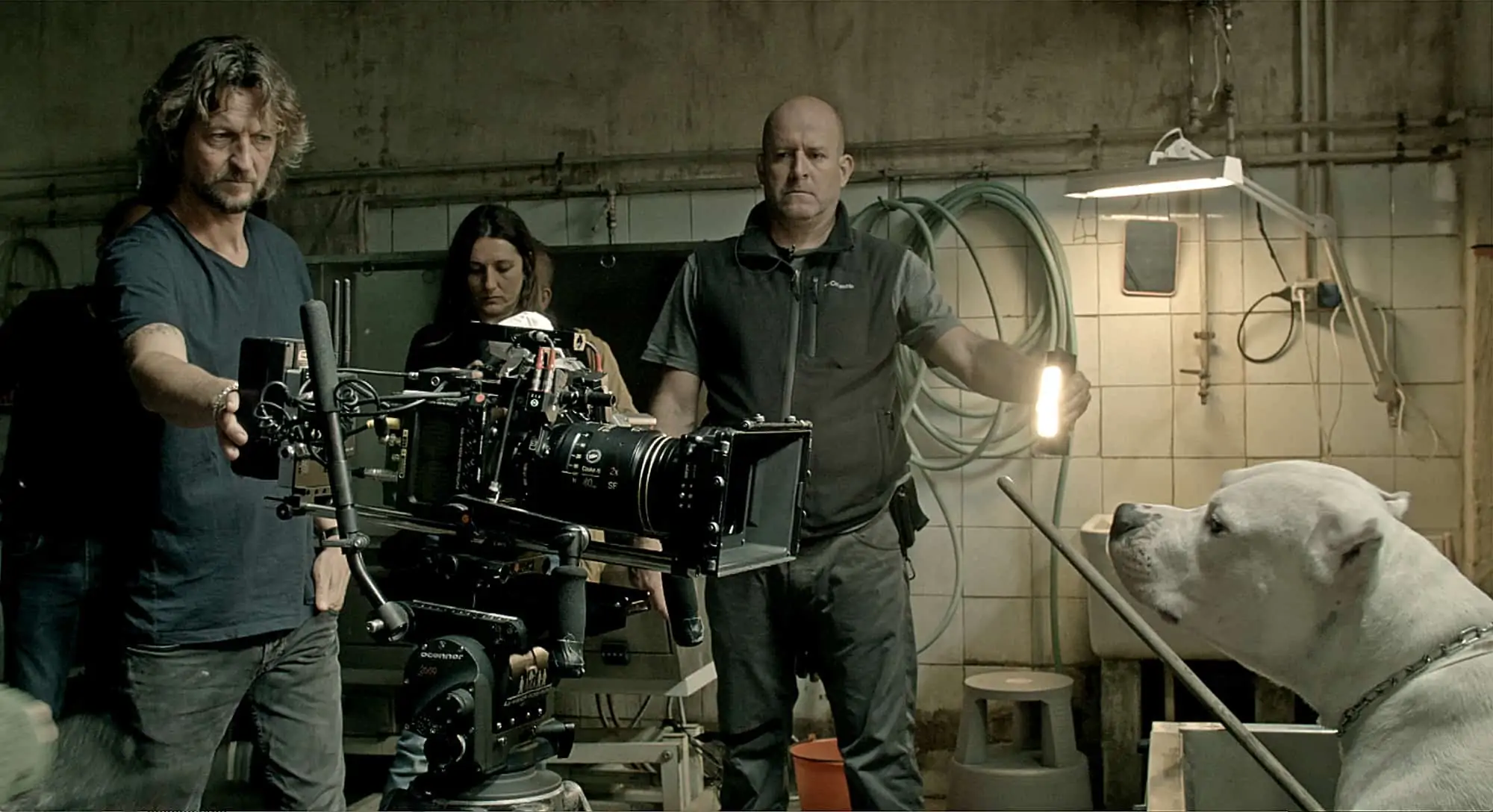

"Originally we discussed if we should shoot Dogman on film," says Brüel. "But the film labs in Rome were closed down, and we would have to wait two or three days to get the rushes back from London or Germany. So, we ended up shooting on ARRI Alexa. We used Cooke Anamorphic SF lenses. They're a little bit softer. In my opinion, it's good when you're shooting digital to use lenses which are not too sharp, something a bit more organic.

"We liked to use the 40mm Anamorphic for the close-ups, which I think worked really well," he says. "It adds this almost three-dimensional feel to the face; this cine wide-angle lens lets you feel really 'close and present' to the actor."

Currently working again with Garrone, on Pinocchio, Brüel describes Dogman as "almost a project that came out of a drawer" before the collaboration on the bigger fantasy period piece began.

"Dogman was very low budget and had to be lightweight in terms of how we shot it," he says. "It all happened very quickly. There was almost no prep. My focus puller Eleonora Patriarca did an amazing job, shooting handheld mostly full open at T-Stop 2.3 with no rehearsals. Dimitri Capuani also did a great job as production designer."

Not to give too much away of the plot, one notable scene involves an actor scaling the outside of a house to stop a Chihuahua's owner from getting a chilly reception, "For this we used a big Technocrane 50, but it was mainly handheld and Steadicam [on the production]," says Brüel. "We had a few long dolly shots, but only five or six in the entire movie."

Garonne operated the camera a lot. "He loves to operate it handheld, and I'd say around 80 per cent of the camera work on this film is by him, and the rest is Steadicam. Maybe two per cent is me, and that was mainly down low shots of dogs."

When it's mentioned how close this sounds to documentary filming, Brüel agrees. "It is! That is how we shot it. I cannot praise my gaffer Alessio Bramucci enough, the patience and the hard work he and his guys put into this. Without them, it would have been absolutely impossible to work this way."

The lack of rehearsals meant it was also very difficult to plan lighting - but with so many night scenes, preparation had to be made. Bramucci and Brüel devised a plan to tackle this.

"We were shooting outside of Naples, in this very rundown place," says Brüel. "The area we shot was quite contained, so we could actually pretty much light the scene in 360-degrees. It sounds crazy, but we did it very cheaply. We had a week's prep before we actually started shooting, so we spent two days pre-lighting the square and the small alleys around it."

Thinking ahead, the team scouted out where shooting might occur and placed practical lighting in preparation. "We had these old street lamps - so we'd find an interesting little alley and put a street light there, or put some fluorescent tubes on a back wall. As much as we could.

"We put 10K and 5K lights on the rooftops, a lighting technique I actually have been wanting to try out for some years," Brüel continues. "I imagine this was the way they lit the old Black and white studio movies in Hollywood."

This was only one of the interesting solutions he adopted.

"The whole square was basically on one big dimmer board," he explains. "We could control everything very quickly, every light. So, it was like: 'now the camera's pointing that way, OK, put that on, put the others off!' It was very scary, but also in a way, quite exciting. It also was very efficient. We were supposed to shoot in nine weeks, and we finished after seven."

"For me the most exciting part of Dogman was to let go of all control, to go with the flow and really trust Matteo and his way of working rather than work against it. Then realising how little light we could use, what we could get away with."

- Nicolaj Brüel DFF

The front room of the grooming parlour is often bathed in ambient sunlight, but the back room where the work goes on is starkly delineated with top lights, which not only served to centre the dogs in the frame but also added a great deal of shadow.

"We started off having the soft sunlight coming into Dogman's shop," explains Brüel. "As the story grows darker, we would increase the contrast. Instead of warm colours, we'd go for more greens, and blues, and obviously go darker. The front of the shop is a façade, I guess. A metaphor for his life. A front which is bright and friendly and a back side which is much darker."

The colour palette was also chosen carefully to lift the mood in certain other places in the story. Marcello is rewarded for his loyalty to local thug Simone when the gangster takes him to a nightclub. Brüel tried to provide a sharp contrast to the rest of the story here: "I thought the club needed to feel completely different, more modern," he says. "For me, the rest of the movie has a feel of a '70s or '80s film. But suddenly he's brought into this new world, outside the village, with pretty women and loads of techno music. We used red colours, highlights, and flares in the lens, trying to add a more modern look here.

"It's always interesting when you're telling a story, to break it up once in a while," he explains. "It would have been easy to shoot the whole thing in the back room, with the dogs being top lit, and blues and greens and darkness. If you do that for an entire movie, that becomes your white balance in a way. You simply get used to the otherwise quite stark look and it does not feel as effective anymore. So, you have to plan to have some change of visual style to wake the spectator up. When we come back to the village, you know you're in a world that you know: 'OK this is normal now'."

A similar approach was taken with scenes where Marcello takes his daughter on scuba-diving trips [with underwater camera work by Aldo Chessari]. "That was the same thing, to take Marcello away from the neighbourhood, away from the square where everything happens, and into another life," says Brüel. "He wants to get away from the dogs, from the violence of the village, he wants to be a good father to spend time with his daughter. The sun, water and nature, is a contrast to the darkness of the neighbourhood, his real life. He hopes and dreams of getting out, but he's completely trapped in that world."

While pre-lighting the square, Brüel created some looks for the interiors, and some for the night scenes. "I think we had between five and seven LUTs, and some specific looks for the separate scenes," he recalls. He also used Blackmagic Design DaVinci Resolve to colour grade on set.

"In the days of film, the DP was the only one who knew how the scene was going to end up looking, we were the ones who had the light meter, and control of lighting and colours. Now, shooting digital, you have a really good monitor, and everyone can have an opinion and a say on the look and everything else. If you show something random, the director might get used to that, sitting month after month in the editing suite, and find it difficult to get away from that look. So nowadays I try to get it as close to the final look on the monitor on the set, so everybody including the director can get used to that look."

"For me the most exciting part of Dogman was to let go of all control, to go with the flow and really trust Matteo and his way of working rather than work against it," says Brüel. "Then realising how little light we could use, what we could get away with. It was a completely different approach to filmmaking, and I think in this case it actually added something.

"I think it's important to say that Matteo manages to stay in charge," he concludes. "He's the captain of the ship. He is both the author and the creator of Dogman. It's his vision and it's important that he is allowed to create in that way. It's a true art project."