REACHING NEW HEIGHTS

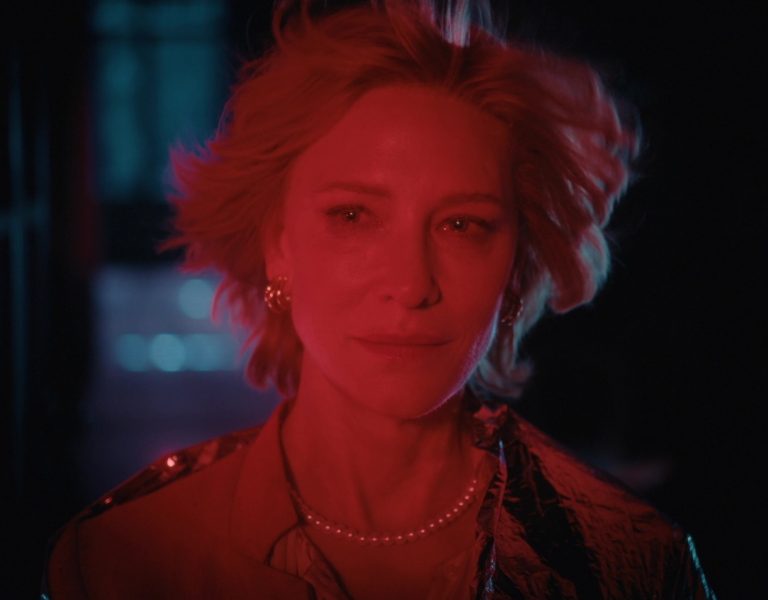

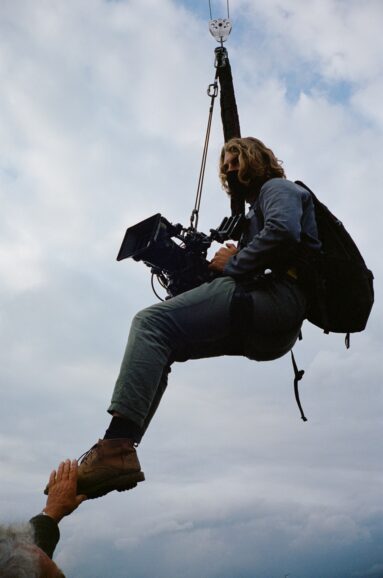

Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No, it’s Justin Brown soaring above the fields, shooting a Burberry spot. The cinematographer reveals how a dreamlike concept was brought to life as he took flight with airborne actors to capture a unique commercial with sky high ambitions.

Audiences and filmmakers alike have been wowed by the high-flying ambition and technique on display in Burberry’s Open Spaces commercial. Blurring the lines between reality and fantasy and encouraging people to “embrace the outdoors and explore new places and spaces”, Riff Raff Films’ spot sees four gravity-defying characters take flight as wind ripples through golden cornfields. Spinning and tumbling through the air, they then bound through a forest before the four bodies soar over clifftops in stunning airborne choreography to unite as one above the sea.

The commercial’s directors – Clement Gallet and Leo Berne from The Megaforce, a team of four directors who work in pairs – wanted to capture as much in camera as possible and for the camera to fly with the performers. The seemingly impossible challenge saw cinematographer Justin Brown and the crew embark on a mission to shoot the acrobats’ phenomenal choreography using a combination of wire work, practical helicopter shots, Russian Arm, Steadicam, and Technocrane.

“Most commercial treatments have been written by an agency which the director riffs off, but The Megaforce directors came up with the concept and had a lot of creative freedom,” says Brown. “The overriding ambition was to create a dreamlike feeling, and then the structure was established by Leo and Clement during rehearsals. They knew they wanted to start in a field, move through woods, back to fields, and then open sky. But how we would get from A to B was still to be figured out which was incredibly exciting.”

Brown, Gallet, and Berne had not seen anything quite like the dreamlike concept they envisaged creating and which had not been captured using green screen. “We looked at Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon as to how the actors might move from A to B, but not the way it was filmed because it was captured on quite long lenses or using a track on a rooftop, with the actors on lateral wire,” says Brown.

The first facet of the concept to explore was how to make the acrobats fly. Initially the best solution was deemed to be using two cranes with a single straight wire going from A to B, or a few wires, depending on how many actors were flying at the time. But as that proved too difficult to achieve within the timeframe, the crew opted for a huge construction crane that would rotate on a 180-degree arc and which the actors would be suspended from.

Next, the crew needed to determine how to capture the action. At first, they considered the Russian Arm approach or using a 100-foot Technocrane, but then they realised the best solution would be for Brown to strap into the harness and the wire rig with the actors. “This meant we really felt that motion because I kept the same distance from the actors throughout the whole shoot,” he says. “It was almost as if there was a drone flying near them.”

To perfect the technique before the shoot, the directors spent three days in a studio, finalising the choreography with the acrobats. The crane was then installed at Dunsfold Aerodrome in Surrey where the rig was refined, and its weight limit was determined during rehearsals.

“I had to carry the camera, batteries, and film, so we needed to work out the total weight the wire could carry,” says Brown. “To make the shoot achievable in terms of physics, I was positioned nearest to the arc. Once we had perfected the camera position at Dunsfold Airfield, we spent three further rehearsal days figuring out the shots. The actors’ movement feels very free and fluid, but to create that feeling, especially between the different locations, required a lot of rehearsal.”

Safety was always a priority, headed up by stunt safety specialist and wire specialist Bob Scholfield. “That’s why calculating my weight was so important. If I was a stone or two heavier, I would not have been able to ride the rig,” says Brown. “The actors were completely safe at all times and each person was on a specific wire, which was controlled by a specific bell ringer.”

The shots in the cornfield in Coulsdon and the Surrey airfield were captured using a rotating crane and a mixture of Russian Arm, 50-foot Technocrane, Steadicam operated by Richard Lewis, and handheld, with an aim to feel as free as possible. The sequences in the forest – the same space where Brown captured scenes for The End of the Fucking World – were achieved using straight wires and a combination of Russian Arm and handheld.

The shoot was not only challenging due to the technically complex processes involved; filming during the pandemic presented other obstacles. “There was a specific radius in which the construction crane could move, and it had to be in a position which meant we wouldn’t have to retract the arm too much and the arm would not need to spin too fast to keep up with the actors,” says Brown.

“All of this calculation was carried out and then our key grip Tony Shultz got COVID, so we had to think on the fly. We ended up moving some of those Technocrane shots to Russian Arm. Working with the seven-metre extension arm meant we could get the camera completely over the grass and in between the camera and the actors, so you never see trampled grass in the shot.”

When filming in the woods, a Flight head stabilised head on a Russian Arm was also used because the camera needed to shoot straight up or straight back to capture the actors as if they were skipping along the tree trunks. “We also worked with a custom 90-degree plate we made for the Flight head to achieve the right camera angle without the wheels being too crazily inverted,” adds Brown.

On one of the Technocrane days, Brown also worked with the Libra head to achieve an effect as if he was being suspended from the crane. “In the Libra’s control unit, where the wheels are attached, there’s a little gyroscope,” he says. “So, you can pull the wheels off, attach a monitor to the unit that the wheels sit on, and put that unit on your shoulder. This means you can look at a monitor and move the camera left and right or change the roll axis which makes it feel like the camera is handheld.”

Some sequences that might appear as one shot in fact comprised of multiple elements. The opening scene of the commercial, when the four actors are walking and notice the wind approaching, is made up of three shots. “We Steadicammed back with the actors as they walked and then as the camera panned, we overlapped that with a static shot that captured the wind approaching, which was created by a helicopter.”

Once that element had been captured, the camera was placed back on the Technocrane, where it spun alongside the actors, as the arm swung to the left. “And then I went handheld as we flew back with the actors which was such an amazing experience,” says Brown.

A unique texture

Open Spaces was captured on Kodak Vision 3 500T 5219 using an Arriflex 235 paired with 14mm and 16mm ARRI Master Primes, with the camera package supplied by Panavision. Brown was delighted the directors pushed to shoot on film as “often with commercials, it’s difficult for the production company to push that through to the agency, because a lot of new creatives haven’t worked on film. So, it can be seen as a bit of a risk because from a viewing perspective there are no HD taps, even though in reality it is not a risk.”

Shooting on film produces a texture that Brown believes cannot be created digitally. “We could capture the extreme highlights we were dealing with” he says. “There were points where I was unable to ride the iris because I was flying on the rig with the acrobats, so I could set the exposure to where I was comfortable, knowing the highlight would never burn out.

“As film stocks are quite clean still, even if you expose well on 500T you don’t feel the grain too much. So, because the highlight range is so good on the 500T we ended up pushing one stop to get a bit more grain structure.”

There were also times when the camera was shooting directly into sun through wispy clouds, which the cinematographer feels a digital camera would not have been able to capture with such success. “It was also incredible to still be able to capture the detail in the clothes – the key aim of the commercial – and not lose any detail, or for the clothes to become too granular due to the grain structure.”

The commercial was framed for a 3:2 ratio as it was considered “a more photographic aspect ratio” and enabled Brown to “keep some of the vertical height of the 4:3” he was shooting 4-perf on the Arriflex 235. “Having that vertical height, meant the actors would sit more easily in the frame,” he says. “And if we did end up misframing a touch if I swung a little too close on the rig, they could just be shifted up a little but still not be compromised at the bottom end.”

The majority of the commercial – which was captured handheld – was shot on the Arriflex 235, with some filmed using the Arricam LT with the Russian Arm and Technocrane. “The 235 is extremely lightweight and we pulled off the eyepiece most of the time because I was operating off a tiny onboard monitor,” says Brown. “The Master Primes are my preferred spherical lens – the highlights hold so well, and the colour rendition is excellent.”

Brown has recently acquired new shape grips which allowed him to twist and lock the handheld bars quickly and move the camera into a variety of positions while it was suspended from a tight bungee wire above his head. “I could just fly and point the camera, knowing I was capturing the actors in the correct place,” he says. “All the batteries, the Teradek, and the operation for the LCS was in the backpack I wore, so the camera package was very light.”

The ambitious feat would not have been possible without second unit DP David Bird – who filled in for one day of reshoots – and focus puller Chaz Leon. “I wasn’t shooting at too deep a stop, around T4. However, I was around 100 feet away from the actors and Chaz was still able to keep it completely sharp.”

Although lighting was mainly natural, shots such as the scene where the actors enter the forest from the field required Brown to work with gaffer Craig Davis to illuminate the space. “It was very dark, so we used 10 Half Wendys gelled with half CTB to create a sunset feeling. The actors wore black clothes, and we were looking up at them, so we needed some sort of an edge light on them as if the sun was poking through. The distance they were travelling also meant we needed a lot of light.”

In the grade, Matthieu Toullet, creative director of colour at MPC, helped achieve a dreamlike quality whilst still ensuring the colour – including the shades of the clothes and the cornfields – was true and not skewed in a warm or cool direction. “We worked with a neutral to warm skin tone with a warm spectral highlight and a black that was a little crushed, but had a bit of density,” says Brown. “Pushing the film one stop then meant we had a little more texture across the mid tones and highlights.”

While most of the commercial was captured in camera, visual effects sorcery from the masters at MPC was vital, seamlessly stitching together sequences, removing wires, and creating CG scenery and photogrammetry.

“The one shot we needed green screen for was where the actors fly over the water. That environment was created in post and then we shot the actors flying over a small strip of water,” says Brown. “So, the interaction and the reflection of them was in camera, but the rest was CGI with a green screen behind them.”

The shot comprised a Russian Arm shot of the actors holding one another and a drone shot captured in the south of England. The end cliff scene was camera tracked and post visualised by MPC with a CG cliff to provide an accurate guide for the drone plate photography. “We combined the plate of the cliff by matching the different cameras in CG, a little beauty work on the cliff edge, and sunset feel for the very end,” says Alex Lovejoy, MPC creative director.

Houdini’s procedural scatter tools were also used to quickly iterate the forest elements. “SpeedTree (tree modelling software) was integral to the forest sequence. It gave us a strong starting point for all the trees and vegetation, allowing us to churn out variations with preset dynamics,” adds William Laban, CG supervisor at MPC. “We also went back to the shoot location with a DJI Mavic Air 2 to shoot some high-resolution pictures to project as textures in 3D. There was a plethora of scatter systems for the forest, custom FX sims for the grass, and water interactions.”

Many people have asked Brown if the whole commercial was created using visual effects. “This is good and bad, I guess,” he says. “But what many don’t realise is how much sky replacement MPC did to match location A to location B. So, the camera would go through a 180-degree spin, with the first 90 degrees at location A and the second at location B. We matched the heights and the time of day, but the texture of the grass and the background was different and had to be completely blended.

“The MPC team never tell you something isn’t possible. They’re fully on board creatively to make the project a success. And because the directors of this commercial, Clement and Leo, are so technically excellent, they were able – with the VFX team and I – to work around any technical issues or challenges faced to realise the creative vision.”