Bridging the divide

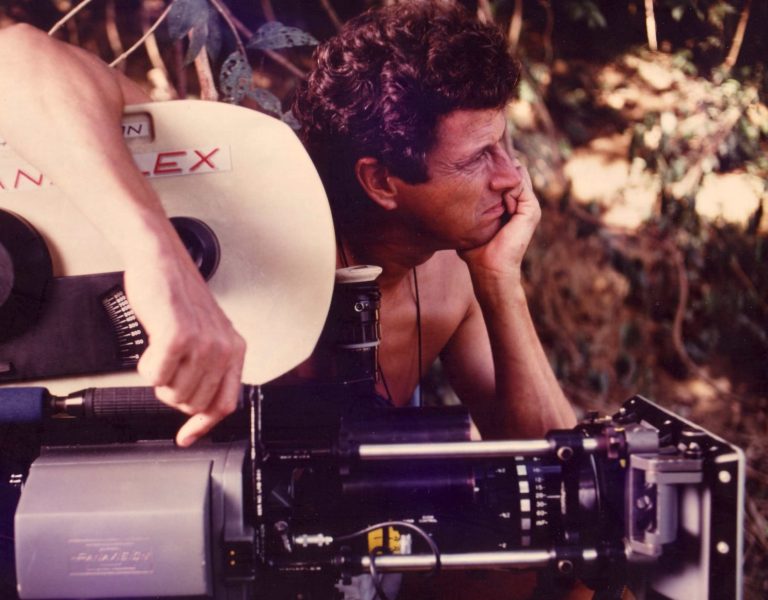

Across his 30-year career, French cinematographer Jean Marc Selva AFC has seized the ever-increasing opportunities to work on international features. Delve into his work on the Hindi-language action film Lakadbaggha as he shares the fun and thrills of finding his feet in the world of Indian cinema.

The universal language of film transcends any linguistic or cultural barriers on set, as Jean Marc Selva AFC has discovered during a career behind the camera that has taken him around the world. Thanks to a lifelong love of travel, the French cinematographer has largely been shooting projects outside of the Hexagone for the past 15 years – including his sixth Indian film, Lakadbaggha.

“I’ve always been enthusiastic about discovering new places, new lifestyles and customs,” he muses. “If I weren’t a cinematographer, I would have probably found something else to do that involves travelling too. If ‘traveller’ was a profession in itself, that’s probably what I’d do!”

Growing up in the south of France, Selva didn’t find his calling for cinematography until he was older. “I realised that filmmaking allowed me to put in practice many of the things I like to do: photography, storytelling, speaking foreign languages, travelling, and experiencing other cultures.”

Highlights of his 30 years in filmmaking include French features like Ce que mes yeux ont vu (dir. Laurent de Bartillat), complemented by international projects including Indian coming-of-age drama No Fathers in Kashmir (dir. Ashvin Kumar) and Morocco-France-Belgium co-production Un été a Boujad (dir. Omar Mouldouira). Ever since he joined the industry, it wasn’t uncommon for him to be sent on shoots around the world; nowadays, he spends half the year away from his home in Paris.

“I love to find the universal elements in the stories I shoot,” he notes. “This one aspect of the story any person from any country can identify with. That’s what I like to build on in my work. Human emotions have no nationality. Wherever we come from, we have an awful lot in common.”

Global appeal

In recent years, Selva has found a particular affinity with the art of Indian filmmaking. Indian cinema has gone from strength to strength: the Indian media and entertainment industry was valued at $26 billion in 2022 and enjoyed its second-biggest box office year ever in 2022, with $1.28 billion in ticket sales. Lakadbaggha premiered in 2023 to a packed house at the Kolkata International Film Festival, where it received a standing ovation. Set in Kolkata and played out in the Hindi language, Victor Mukherjee’s high-octane action thriller follows Arjun (Anshuman Jha), a martial arts trainer-turnedvigilante after his dog, Shanku, goes missing. While trying to find his lost companion, Arjun encounters an Indian black-striped hyena (lakadbaggha is Hindi for hyena) and finds out about Kolkata’s illegal animal trade – a narrative inspired by real events in the city.

Jha and Selva had first met five years prior to Lakadbaggha on 2018’s No Fathers in Kashmir, which follows a British-Kashmiri teenager who meets her Indian grandparents for the first time. This time around, Jha, who is also a producer, brought “an action film, involving chases, numerous Krav Maga choreographed fights between a vigilante and the animal trafficking Kolkata mob,” Selva remembers. “This sounded like fun to shoot and a meaningful story to tell – plus it took place in India, somewhere I love to go to – so I did not hesitate [to accept].”

Lakadbaggha marks Selva’s first project with director Mukerjhee, but they quickly found their shorthand despite a limited prep. In their early discussions about Lakadbaggha’s look and mood, they examined references including Night in Paradise, The Equalizer, and The Night Comes For Us, as well as Bruce Lee’s older films for their “raw” quality.

“Ultimately, films find their own look,” Selva continues. “The more you talk about it, the more you work on it, the look reveals itself to you. The scenes and the place you shoot in invite you to go a certain way with your lighting, your framing. When it stays in your head long enough the film starts to communicate with you on an almost subliminal level. Also, the locations, especially in a place like India which has a very strong visual identity, inevitably bend the look a little.”

Selva tested a variety of camera and lens combinations for Lakadbaggha. For a while he was planning on using the Sony Venice, including its Rialto extension system, but when the Rialto turned out to be unavailable, the ARRI Alexa Mini LF was an ideal solution for the largely one-camera shoot. “I was comfortable using this compact lightweight camera given that I was going to do a lot of handheld work in the fight scenes. Also I needed light and fast lenses as I had a lot of night scenes in very low light situations plus I wanted to have a rather shallow depth of field look,” says the DP.

After a weight, size and look comparison, Selva settled on the Zeiss Supreme prime lenses. “Initially we had been thinking about shooting on anamorphic lenses but decided to crop at 2.39 instead and leave the extra space above and under the picture as we also had a lot of VFX to do.”

Other kit included a Ronin 2 with a Tilta Armorman, a Steadicam, an EasyRig, as well as dolly and tracks. “No crane was used as we wanted to remain raw and real – nor did we shoot drone footage,” he adds.

When deciding how to approach the lensing of Arjun’s character, the filmmakers decided to mix two shooting styles to reflect his double identity – one as a teacher and one as a vigilante. The same principles used for the camera were applied to lighting.

Selva explains: “We had one more subdued and gentle approach for the scenes where the character is seen as a shy courier boy and another style which was more real and raw. For the first one the camera was on the dolly or on a tripod and the moves were cleaner while for the second we were more handheld, almost a documentary style.”

Crafting the titular hyena and integrating it into the visual storytelling involved a thorough collaboration with the VFX team, led by Rajeev Kumar. “Animals with fur are not easy to do, especially while they are moving through space,” notes Selva. “While shooting we had to leave empty spaces in our frames to make room for the animal later. A VFX supervisor was on set with us.

“The animal was created when I was back in France. Many work-in-progress files went back and forth between Mumbai and Paris, when we tweaked many details from quality of movements, perspective, hair and more.”

The film is peppered with intense fight scenes involving Krav Maga, a martial art originally developed for the Israel Defence Forces. The filmmakers didn’t want these to feel slick, but rather feel like a real street fight. To achieve this, they enlisted the help of action directors Vicky Arora of Force Square and Ketcha Khamphakdee of Jeika Stunts.

“The sequences are really long, but luckily we work in slices, so we had to memorise the camera positions for eight to 10 moves at a time,” Selva says. “Crafting the fights involves a lot of trickery and has a lot to do with camera placement to give the illusion that people are being hit. It’s a painstaking process.”

For the cinematographer, shooting these fight scenes was an exciting challenge – the first scene between Jha and some criminals was shot at night in a large industrial compound on the first day of the shoot. “Due to limited availability, we had a very ambitious schedule of five sub-locations in the same night,” Selva recalls. “That put a lot of pressure on the crew right away. The only way to win this fight was to split the electric crew over the different sets. I kept going back and forth between the main location (the warehouse) and the others four to have them ready in time.”

Local intel

To assist him on the shoot, Selva brought in Santosh Singh Kumar, a first AC that he’d met on a previous Indian film whom he trusted and liked to work with. His collaboration with gaffer Mohsin Rehman was new. “His English was not very good,” the DP admits, “but he turned out to be an essential collaborator. Though still young, he already has many years of experience as he started working on film very early in life. Again, this shows that language is not necessarily a problem in filmmaking, which really is a universal language.”

One of the most striking differences that Selva has found between European and Indian sets is the number of crew and their roles. He explains that there are lots more people in the crew than in Europe and it is not always easy to figure out what certain crew members’ roles are at the beginning.

“The DP in India is helped by the first assistant in lighting, much in the way a gaffer may do [in Europe] when they know the DP well enough,” he notes. “They rough out the lighting or even go quite far into it before the DP is there. I do not work like that, so it took some acceptance from the crew.” It can also take some convincing to make the crew do things in a different way than the norm there, like lighting with unusual tools. “I had a scene where I wanted to use sodium vapour lights but could not find them at the rental and had to have them bought. But I could see the electric crew felt a little uncomfortable using them.”

Working in a location as vibrant as India was an exhilarating experience for the DP and, despite its challenges, one he enjoyed. “The working hours can be quite long and the days off not always observed. Other challenges are the noise level, the heat, the dust, the traffic… It certainly is an exotic experience. But one gets quickly used to it when one has to deliver.

“It helps that the crews are generally hard working and dedicated, always helpful and friendly too. The shoot was well organised and the equipment in line with international standards. I would say for a European working there, it requires flexibility as well as endurance.”

Selva returned to Mumbai for the grade, working with colourist Kiran Kota Kumar at Prasad Labs. “He is very fast and very experienced with Baselight,” the DP notes. And it looks like his collaboration with Jha is set to grow even stronger. “We’re developing a sequel, of which I cannot say too much for now. Only that it will bring us back to Kolkata and then in another country yet more exotic and interesting to work in…”

Watch Jean-Marc Selva AFC’s insightful interview with British Cinematographer here, where he tells us more about his career to date and his influences and inspirations.