Living the dream

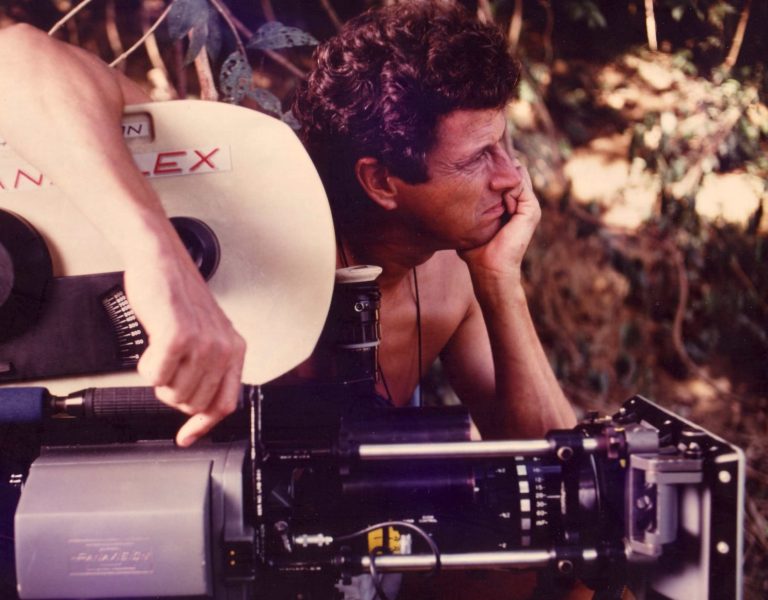

Tasked with breathing new life into a Kurosawa masterpiece, Jamie D. Ramsay SASC relished the challenge of crafting Living’s carefully composed look. Here, the cinematographer lifts the curtain on his work on the film, which reunited him with director Oliver Hermanus.

It’s a story that stands the test of both time and geography: a worn-down civil servant rediscovers his zest for life following a terminal cancer diagnosis. Seventy years ago, the Japanese drama Ikiru (itself partly inspired by Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich) was received to critical acclaim; now Living, which transplants Akira Kurosawa’s story to the West, is charming audiences and reviewers alike with its touching take on life – and death.

With South African director Oliver Hermanus taking up Kurosawa’s mantle for Living, it made perfect sense to bring his long-time collaborator (and fellow countryman) Jamie D. Ramsay SASC on board. The duo have worked together on and off since 2006, mostly recently on 2019’s queer war drama Moffie, which earned Ramsay a Best Cinematography nod at the British Independent Film Awards. Living presented the pair with the fresh challenge of honouring Kurosawa’s legacy yet crafting their own visual approach to the Japanese classic.

“When I read the script, what I really liked – and this is the tricky part when it comes to doing remakes of films – is that line between an homage and having your own language and tipping the hat respectfully to the original,” Ramsay muses. “I thought it sat in a truly British environment so comfortably and proves that this idea of the lonely working man’s plight is a global, timeless story that can be blueprinted onto so many different cultures and times.”

A shared aspect

It was important for both Ramsay and Hermanus to never be overly swayed by Ikiru and the DP watched it just once in early prep. Although the pair clearly didn’t want to create a carbon copy of the original, they were keen to keep Living faithful to its 1950s setting. Shooting a period piece allows him more freedom from a cinematography standpoint, Ramsay notes. “With regard to your style of capture, and how you want to shoot and light it, it always seems to me so much more robust in a period piece. Firstly, you have wonderful reference material to inspire you, but secondly, the world’s your oyster in terms of the visual language.”

An obvious nod to Ikiru comes in using the same 1.33:1 aspect ratio, with the squarer frame serving as an interesting metaphor for the predicament of Bill Nighy’s reformed workaholic, Mr. Williams. Ramsay explains: “Simply put, the box created this structure and rigidity to the image. It came from the idea of a caged, post-war, austere British life where the people were working for the country and not necessarily themselves. It was a life constrained to the social dimensions imparted on society, so if you are from this middle class, that’s where you’ll stay.

“Another aspect to it was the idea of when you shoot with an aspect ratio with high vertical dimensions, you cut off any superfluous information on the sides, which I feel really dials you into the character narrative to a great extent. It really becomes about the individual in the frame. The square of the composition, is also great for group shots because you can quite easily do three or four person compositions that feel personable to each person in the frame, rather than losing the ones on the side and making something of the one in the middle.”

Inspirations and influences

When Ramsay joined pre-production in early 2021, Hermanus had already undertaken an extensive level of research into the project. In their initial conversations about the film’s look, the DP and director’s references focused on stills photography: work by the likes of Saul Leiter, Henri Cartier-Bresson, James Nachtwey and Vivian Maier. Leiter’s voyeuristic style partly inspired the decision to shoot characters with objects in the foreground to create a sense of isolation, even in a busy setting like Mr. Williams’ office. They also sought inspiration from compositions in films such as Letters from Iwo Jima, From Here to Eternity, and Schindler’s List.

Ramsay was aiming for a look “reminiscent of crisp film print that has been hand processed to perfection”. Deciding against shooting on film, he explains: “The print feeling was a more stills photography-driven look – that different way of processing and exposing. Even if film was on the cards, I don’t know if I’d have opted for it because I have so much more control in getting that look on digital.”

The cinematographer likes to get involved as much as possible with the art department on his projects and enjoyed a fruitful collaboration with production designer Helen Scott and costume designer Sandy Powell on Living. One of the first meetings for the project brought together Ramsay, Hermanus, Scott and Powell to pin down the film’s overall mood and colour palette.

“Post-war UK felt quite desaturated and dour, with a lot of concrete, but we didn’t want the film to feel that way,” he says. “One of the things we came to when we were looking at references was that the colour pop came in through characters and props. The background base we kept as greys or desaturated autumnals, then you have your secondary layer, which was going to be your props, which would be carefully chosen primaries. Your third layer, which is Sandy’s world, is the wonderful wardrobe – that was where the key colour personality was going to come in.” To contrast London life with Mr Williams’ joyful segue to Brighton, the team leant on more primary colours for a fun holiday feel.

Another collaborator from Moffie, Company 3’s Joseph Bicknell, was Living’s colourist. During prep, Ramsay sent him a handful of stills imagery, all from post-war UK and using early Kodachrome 35mm stock, and after some back-and-forth and playing around with test footage, they developed some shooting looks that were used on set. “What was great about having Joseph involved in pre-production meant that he was creatively invested in this right from the beginning,” Ramsay comments. “We all knew going in this was going to be a crunchy film, where we’ll lean into the contrast, and he was all for it. We’ve grown this look together with Joseph.”

Lenses and locations

Ramsay’s camera package featured the ARRI Alexa Mini because he wanted to shoot open gate, which was close to the aspect ratio they wanted the film to be finished at. The Alexa was paired with the large-format ZEISS Supreme lenses. “We wanted lenses that were close to a good quality stills lens, that would give you this sort of accuracy of a good quality stills lens – something fairly sharp that would cover the entire sensor and give you a completely accurate image,” he explains. “Any kind of personality that we wanted to add to the image, we wanted to do ourselves and allow it to be something we had control of. The choice of these lenses also allowed us a great feeling of contrast and the way these lenses deal with colour is really precise so they just felt like the right choice for this movie.”

Shooting took place mostly on location across South-East England in mid-2021, and the nature of the location-based shoot came with some inherent lighting challenges. London’s County Hall, which hosts Mr. Williams’ stuffy council offices in the film, proved tricky for Ramsay and gaffer Warren Ewen. It didn’t help, Ramsay remembers, that they shot Living during one of the busiest times in UK film history (the post-pandemic production boom of early 2021), so Ewen and his team had to fight tirelessly to secure the right equipment.

“As any of British Cinematographer’s readers will know, the weather in the UK is never very practical when it comes to cinematography,” says Ramsay with a smile. “We had extreme light changes every day when shooting those scenes. Production designer Helen Scott built the office set in County Hall and we had to build a sub-structure within her design that would host our lighting. The only thing we could do was create a constant interior level and tone, but it was always at the mercy of the exposure of the window. We had to have everything on dimmers and wired into a central unit so we could ebb and flow the interior level in order to have a relationship with the window. Most of the monitor stuff is shooting against the windows, so if the window’s reading at 50%, then the lighting inside will have to be at 50%. And if it opens up to 70%, we’d have to lift everything on the inside to 70%. This was happening from shot to shot, so it was really tough to ride that level and keep it constant for visual continuity. It’s one of those things where if you watch the film and don’t see any jumps, it’s a miracle! A lot of stress and focus goes into something as simple as that.”

Another tricky location was the railway station near the beginning of the film. Filming this in a studio was out of the question so the team decamped to Uckfield’s Sheffield Park Station, but the unpredictability of where the train would come to a stop alongside the platform caused some issues.

“On testing, we realised that the stopping of the train was quite an imprecise science,” recalls Ramsay. “The idea I pitched to the team was to shoot inside the hangar at the train station – they had this big old shed where they kept the beautiful old trains. We created a studio inside it and shot all those movement scenes there with our very keen young film students on either side of the train, shaking it, getting blisters all over their hands!

“We got our amazing grip, Jac Hopkins, to build a huge, moving platform that was on two sets of tracks so instead of moving the train, we would actually move the platform. We chroma-keyed beyond the platform then we would slide five or six extras, then Bill, into place each time. When they arrived at the station, the train is actually static but the whole platform is moving. At the beginning when I suggested it, I think everybody’s eyes were rolling to the back of their head. You know what, this is a crazy idea. But in execution it was pretty simple and I think it worked.”

The making of Mr. Williams

Bill Nighy’s solemn civil servant is one of the performances of the veteran actor’s career and has so far resulted in Best Actor nominations at the likes of the Golden Globes, British Independent Film Awards and Critics’ Choice Awards. His foils include his vivacious former colleague Miss Margaret Harris (Aimee-Lou Wood) and a friendly stranger he meets at a seaside café, Mr. Sutherland (Tom Burke), who both help the older man rediscover what it really means to live.

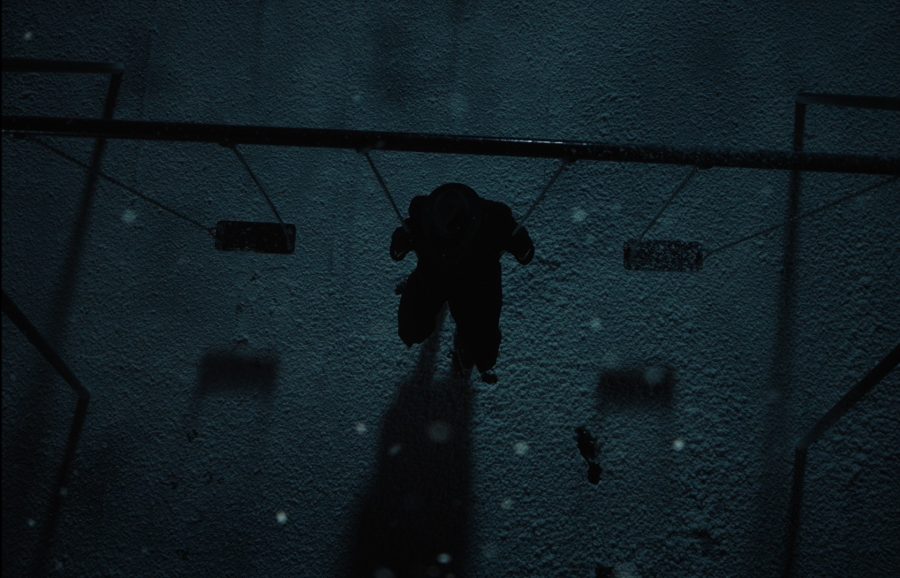

Developing Mr. Williams’ character was aided by Ramsay’s careful compositions. “As Bill’s character gains traction with his choices, the framing allows him to be bolder and more prominent,” says the DP. “As he starts to dominate his circumstance, he starts to dominate the frame more.”

Ramsay also used off-eyeline compositions to enhance the cold, impersonal feeling of the austere 1950s society and the lack of connection between people. He remembers, “A great example for that is the scene where Mr. Williams is having this incredible monologue with Miss Margaret Harris in the bar. He’s confessing his troubles to her and that really affects you emotionally. But this is one of the first times that he really opened up to her. In the edit, Oliver starts to bring that eyeline in closer until a very rare, tight OTS between the two of them.”

A scene in a seaside circus tent heralds Mr. Williams’ decision to start making up for lost time. An important scene for Ramsay, he wanted to mark this turning point in the character’s life as a rebirth and have the interior circus set to feel “womb-like”. Working closely with Helen Scott, they decided the tent’s material would have a red-and-white look that, once lit, would appear skin tone-like. The tent’s lighting would come from the exterior, rather than the key lights being on the interior, and the lighting colour palette would be in the warms.”

“At the point when Bill’s character runs outside and goes to throw up, that’s the birth,” says Ramsay. Here, a run of festoon lighting – a mixture of warm practical bulbs and reds – acted as a metaphor for the umbilical cord. As Mr. Williams’ new friend, Mr. Sutherland, comes to find him, Bill’s character emerges from the darkness – the exact moment of his renaissance. “He’s bathed in a very chiaroscuro way, with one side red and warm as if it’s blood, the DP adds.

An especially poignant moment for cast and crew happened during a scene where Nighy was delivering a touching monologue in a pub. Shooting on location in a traditional inn in the City of London meant grappling with low ceilings and difficulty lighting from the outside, due to the pub being on a main road. Ramsay had to shoot it day-for-night, so couldn’t rely on any outside lighting, and decided to light it practically in a Fifties’ style as much as possible.

“Oliver didn’t want the scene to be interrupted – he wanted it to play almost as a series of masters because Bill had such a stride with his character,” Ramsay recalls. “It was clear from the first rehearsal it was going to be a powerful scene and you could feel it on the crews’ and extras’ faces. It was filmed post-COVID and a lot of people at this stage were dealing with loss. It was a moment where this really resounded with the crew and the cast, what we were talking about and what we were dealing with. Anyone who has worked with Bill will know he’s the most wonderful human and such an inspiring person to have in the industry. In this scene, you’re watching this man who’s had this incredible career play a character that’s coming to the end of his life and it was really heart-breaking. I looked over to my focus puller, Damien Walsh, and we were both choked up. It was one of those moments you remember for the rest of your life.”

Team effort

As much as Living is ostensibly about solitude, Ramsay emphasises how it was a real team effort to craft the film, especially given the post-pandemic challenges, and credits long-time colleagues Walsh and 2nd AC Amy Yeats with keeping his spirits high on set. “We’ve done pretty much most of my formative movies together and they’re a very important part of the team because they are my creative family,” he says. “They’re the support in hard times and the laughs in good times. They’re the ones that you go to when you’re not sure about things. It’s so important for me to have those relationships with my crew because each movie you do is such a huge part of yourself and the time you invest is big portions of your life.”

What are the key lessons he’ll take from the project? “I think the day you stop learning integral lessons as a cinematographer is the day you die. One of the big lessons of this film was having a strength in your decision and trusting your gut. They say the darkest hours are before dawn, and I think that’s the same when executing hard ideas. There’ll be so much pushback, it’s that thing of, if you feel like it’s the right thing, then you must let it go, no matter what.”