WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION

The latest collaboration between Hoyte van Hoytema ASC NSC FSF and Christopher Nolan sees them take on their most groundbreaking creative project yet, bringing the fascinating true story of “father of the atomic bomb”, theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, to the screen.

With over twenty years of experience as a cinematographer, Hoyte van Hoytema ASC NSC FSF has worked with such celebrated directors as Spike Jonze (Her), Sam Mendes (Spectre) and David O. Russell (The Fighter). But it’s his decade-long relationship with Christopher Nolan, a filmmaker renowned for his love of the IMAX format, that has seen him now recognised as one of the world’s leading directors of photography.

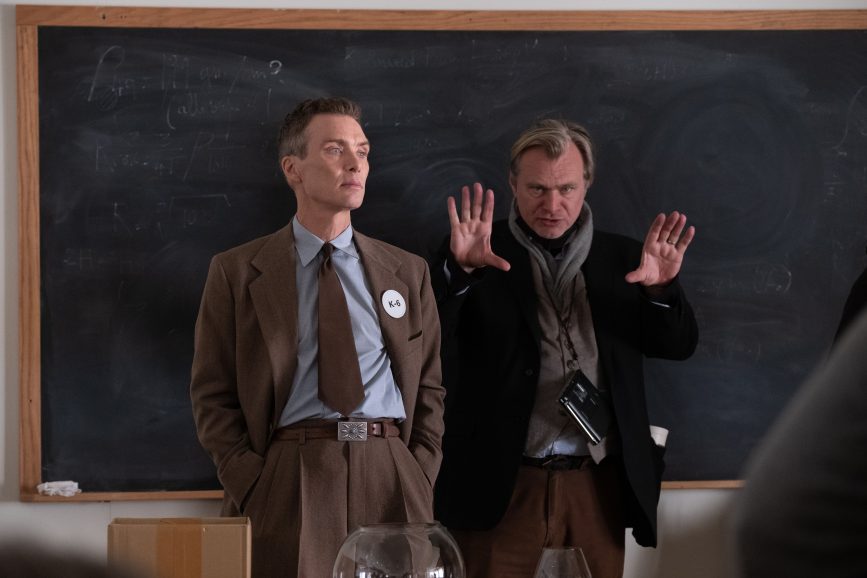

After coming together for sci-fi Interstellar (2014), they reunited on World War II drama Dunkirk (2017), which saw the Dutch-Swedish DP nominated for an Academy Award, and espionage tale Tenet (2020). As complex as these productions were, they pale next to Nolan’s latest film Oppenheimer. A WWII-era biographical drama about the “father of the atomic bomb”, theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, starring Cillian Murphy in the title role, it marks Nolan and van Hoytema’s most groundbreaking collaboration yet.

Typically, though, it began in a very understated way. “It kind of always goes the same with Chris,” explains van Hoytema over Zoom from his home in Stockholm. “He starts figuring it out. We go for lunch. He says, ‘I’ve got something new’ and then usually he invites me to read it at his house. As always, he doesn’t make a lot of copies of his scripts. So, he controls over seeing who reads it.”

This time, van Hoytema, was prepared in advance, knowing that Nolan was taking inspiration from Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. “I think he used the book as very firm ground material. And found within that his own narrative structure, and because of that, he asked me not to read the book first and wait for the script.” Absorbing Nolan’s dense document was just the first stage of an exacting process.

“To a certain extent,” the cinematographer says, “we felt like we somehow had to grasp the grand principles of quantum physics, as well as finding a way for us to make the audience understand it. And, of course, quantum physics is a very abstract form of physics. And there are very few people in this world who really understand it on the level of J. Robert Oppenheimer…he’s a genius. And my mind, for sure, doesn’t even tip to the places that he could go. Yet, we felt as filmmakers we could understand things on an intuitive level.”

Again, he and Nolan resolved to shoot on IMAX 65mm where possible, so captivated are they by the clarity of the images large-format photography can bring. “IMAX is constantly innovating, and they’re constantly helping us solve problems or make those cameras better,” says van Hoytema. “I always compare that camera to, in a way, a Formula One car. It needs a lot of care and a lot of love. But anything that gives images like that, you wouldn’t expect less. It’s not an off-the-shelf thing that just shoots school pictures. In order to get to that very specific level, it just needs service and a very meticulous guidance.”

Van Hoytema has long been a convert of shooting on IMAX, and even recently lensed Jordan Peele’s sci-fi mystery Nope (2022) using the system. “When you shoot on IMAX and you can get something in camera, for an analogue print, you’ll never have to scan your material, digitalise it and then put it back to film, right? If you get something in camera, you can make a contact print of it, which means that for that specific shot, you’ll preserve the full 18K resolution. Which is the richest way to capture anything. There’s not a more refined, not a more depth-giving medium in the world than doing it exactly in that way.”

Nolan has been using IMAX ever since 2008’s The Dark Knight and has long been evangelical about projecting his films in the rarely-used 70mm. “15 perf IMAX 70mm is the highest quality imaging format that’s ever been devised,” he recently stated in a behind-the-scenes promotional film about IMAX usage in Oppenheimer. As van Hoytema explains, “This would have been a very, very different film, if this was a film that had [used] digital cameras. I mean, for starters, the size of the IMAX frame…the way the lens allows an amount of light through and then projected over the big area of negative…it is a very visible enhancement of texture and depth.”

The magic mix

As was the case with van Hoytema’s earlier collaborations with Nolan, Oppenheimer uses a “magic mix” of IMAX and the more “workhorse” 65mm cameras. Unlike the noisy IMAX machines, which make recording actors’ lines almost impossible without recourse to Additional Dialogue Replacement in post-production, shooting on the Panavision Panaflex System 65 Studio Camera allows for the recording of sound and dialogue. “And this film, in comparison to other films, is very dialogue heavy,” he adds.

Yet Oppenheimer presented other unique challenges, with Nolan keen to shoot sequences in both colour and black-and-white. While colour makes up the bulk of the film, detailing Oppenheimer’s subjective experience, the black-and-white scenes show a more objective view of the story. Nolan hasn’t shot in black-and-white since his sophomore feature, Memento (2000), which was filmed on 35mm anamorphic. Returning to black-and-white for Oppenheimer represented a huge test. “We’ve been talking for ages…that our big pipe dream would be to shoot black-and-white film on the big format,” says van Hoytema. “This felt really like the right time.”

His early education at the National Film School in Łódź had already prepped him. “I grew up with black-and-white, in Polish film school. The first two years, we were only allowed to touch black-and-white film, because it narrows down and simplifies very much the way, as a photographer, you can divide an image into lightness and darkness, as opposed to lightness, darkness and colour. So, it’s all about contrast, and it’s all about filtering out what is important and purely doing that with light levels.”

Shooting black-and-white on big format was easier said than done, however. “The problems were that black-and-white film for 65mm didn’t exist. Kodak didn’t produce it, and it didn’t exist in the world. And so we had to ask Kodak to manufacture it for us. There’s a lot of technical challenges with it. For instance, the fact that you cannot just easily run black-and-white film through a camera specifically made for colour, which all has to do with the thickness of the emulsion and the breakability of the material.”

It was a “time of experimentation”, as van Hoytema puts it, as Kodak began sending prototype 65mm black-and-white film stock in sealed boxes to the Oppenheimer team. More was to follow. With the production using the IMAX MSM 9802 MKIII and MKIV cameras, the pressure plates used to hold the film inside each machine needed to be adjusted to accommodate this unique stock. “It was a slow process…even though everybody was excited about it. Nobody really needed convincing,” says van Hoytema.

Initially, the traditional hair-and-make up tests were shot in black-and-white. Nolan and his close team projected the footage at IMAX AMC Universal CityWalk in Los Angeles. “We just realised that this is so special and so beautiful,” says van Hoytema. Even then, there were still many issues to overcome. “I mean, the static in the film is different, the susceptibility to dust is different, the scratching of the negative occurs in different places, or the baths in the lab need to be agitated differently. Otherwise, you’ll get fogging issues. Even though it sounds simple, it’s not obvious at all…we had to keep a very keen eye on the whole process.”

Lensing wizard

At this stage, van Hoytema was something akin to a conductor of an orchestra, working with film specialists, lab technicians and camera engineers. He teamed up once again with Dan Sasaki of Panavision, as they began to devise special equipment for the shoot. “He’s like a lens artist/engineer at Panavision. He’s a wizard when it comes to building optics. He’s somehow that ultimate bridge between visions and dreams and the engineering that is needed to do it…so he’s always with us, developing new things, different lenses and optics that work very specifically for the film.”

In the past, on commercials, van Hoytema has used a ‘snorkel’ macro lens that enables shooting in unusual conditions. “IMAX didn’t have a lens like that. So, Dan built us the IMAX equivalent of a ‘snorkel’ lens – which is a huge, long tube, that was also waterproof, so we could drive it into an aquarium, for instance, and shoot underwater with an IMAX camera or shoot extreme macro shots of particles. It had all to do with the fact that we wanted to see physics, we wanted to be within the world of atoms and, of course, we couldn’t build lenses the size of atoms!”

Away from these specialist tools, van Hoytema favoured 50mm and 80mm lenses – the “two focal lengths that really touch the sweet spot of immersive-ness in IMAX”, he says. “In this case, with a film that consists for a huge percentage of portraits, you have to think very differently about your lenses, than when you do a film that is all about vistas…the 80, it’s a tighter lens, but you can use it also as a wide lens by going further away. And then the 50…you sometimes use it just for pure functional reasons…like you cannot get your camera closer, but you want to be a little bit closer.”

Also collaborating with his regular focus puller Keith B. Davis, this period of development thrilled the cinematographer. “Myself, I love building things,” he explains. “I always get a big kick out of enabling shots or enabling ways of storytelling that you haven’t seen before, and especially in these times where people think they can do whatever they can come up with in CGI…I always like to challenge myself and find the equivalent of a good CGI [shot] in the physical world, because I just think that the physical world brings us a certain level of tangibility that is unobtainable in CGI.”

With the production primarily shooting in Los Alamos and Santa Fe, New Mexico, where the Oppenheimer-led Manhattan Project was secretly established, one of the film’s most spectacular scenes is the ‘Trinity’ test – the first ever detonation of a nuclear weapon, which took place on July 16, 1945, in the Jornada del Muerto desert. Ever the advocate of practical effects, Nolan charged the film’s visual effects supervisor Andrew Jackson of recreating the ‘mushroom cloud’ style explosion without using CGI.

“I mean, the Trinity test is not just an explosion that goes off, but dramatically there’s a lot of stuff happening prior,” says van Hoytema. “We create reality as far as we can. And with smart cutting and generating excitement and action, you hook yourself into the run up towards Trinity.” It was a sequence that took months of forethought. “It’s not like people think…we go out there, and we just set up a big explosion and shoot it with a lot of cameras. Effectively we are a one-camera shoot, so every shot that is made is pivotal. If it’s a close-up or if it’s wider, it’s pivotal to the experience of that event.”

For many of the scenes, van Hoytema was keen to keep the lighting as naturalistic as possible. “With the big format, more and more, I’ve gotten through the years more confident in not over-lighting things, because the format itself has such a natural and wide latitude,” he says. “The big format really doesn’t lie. It is so pure a way of acquiring information and acquiring images that that you cannot get away with things you normally would get away with. And for me the answer is simplification. Find the good places to shoot. Play your scenes smartly and use the natural light.”

While many shooting locations were where the actual events took place, some soundstage-based sets were built by production designer Ruth De Jong. “There’s a White House set, that for practical reasons, we had to build all in the studio,” explains van Hoytema, noting that it immediately presented problems of aesthetic continuity. “Imagine you have a film that has all natural locations and suddenly has a totally artificially-lit set, it gets under even more scrutiny…and then you’re shooting 65mm!”

His approach was a case of softly, softly, as he attempted to simulate reality. “You have a huge amount of light power giving very little effect, because you have softened the light so much. You’re effectively creating an outside world bubble. So, you end up working with all this light power, and then you’re sitting inside a room, and you’ve just about got enough of a reading on your light meter. Those are challenges…to make them [the scenes] feel tangible and scruffy and real like they’re supposed to feel.”

When it came to the grading, the production again worked with FotoKem colour timer Kristen Zimmermann, who previously worked on Dunkirk and Tenet. “She is a pure colourist in the classic way of colour timing,” says van Hoytema. “Chris and I would go in and watch the reels with Kristen…we would literally call out colours. More magenta or more green or a few points brighter, a few points darker.” It is, says the cinematographer, very different to creating a Digital Intermediate (DI) and using a tool like Power Windows to adjust colours accordingly.

“Your analogue film doesn’t have that, but in my opinion also doesn’t need that. So, it’s a very pure way of making prints.” In these analogue sessions, watching the film in real time allows you to experience the film and get a feel for the colours. “I love that process,” he adds. “And I also love that process, of course, because you’re colour timing, and you’re never dealing with compression. You’re literally watching contact prints of original negatives, and you see things straightaway in your colour time sessions with such an immense depth.”

Now Oppenheimer is ready for its global release, the final prints are said to span over 11 miles, weighing 600lbs – with over one hundred 70mm prints made and shown around the world in theatres with specialist equipment. “Everybody has, of course, to be the judge themselves, but I watched the 65mm film prints, as well as the IMAX film prints,” says van Hoytema. “They all have something very special in the way they look, I think, because of this whole elaborate process. It’s something that I think you can’t replicate in a different way.”