Personal Portraits

Dick Pope BSC / Bernie

Personal Portraits

Dick Pope BSC / Bernie

BY: Ron Prince

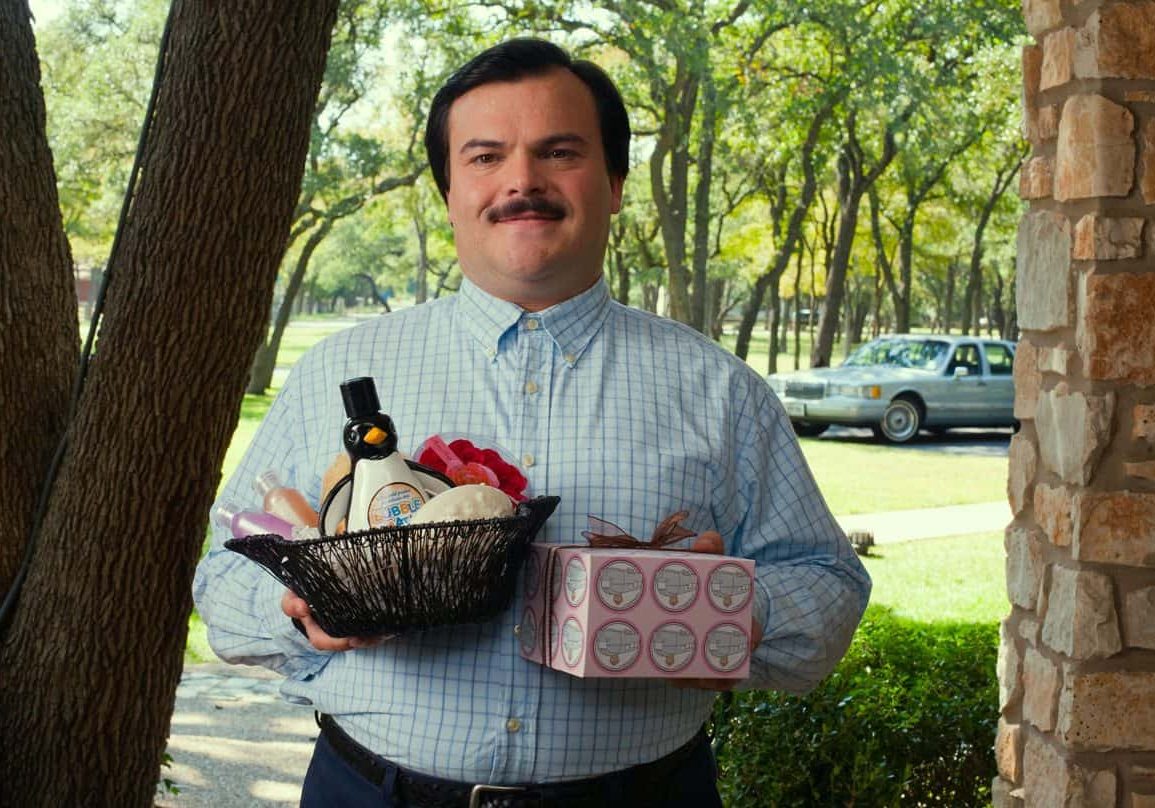

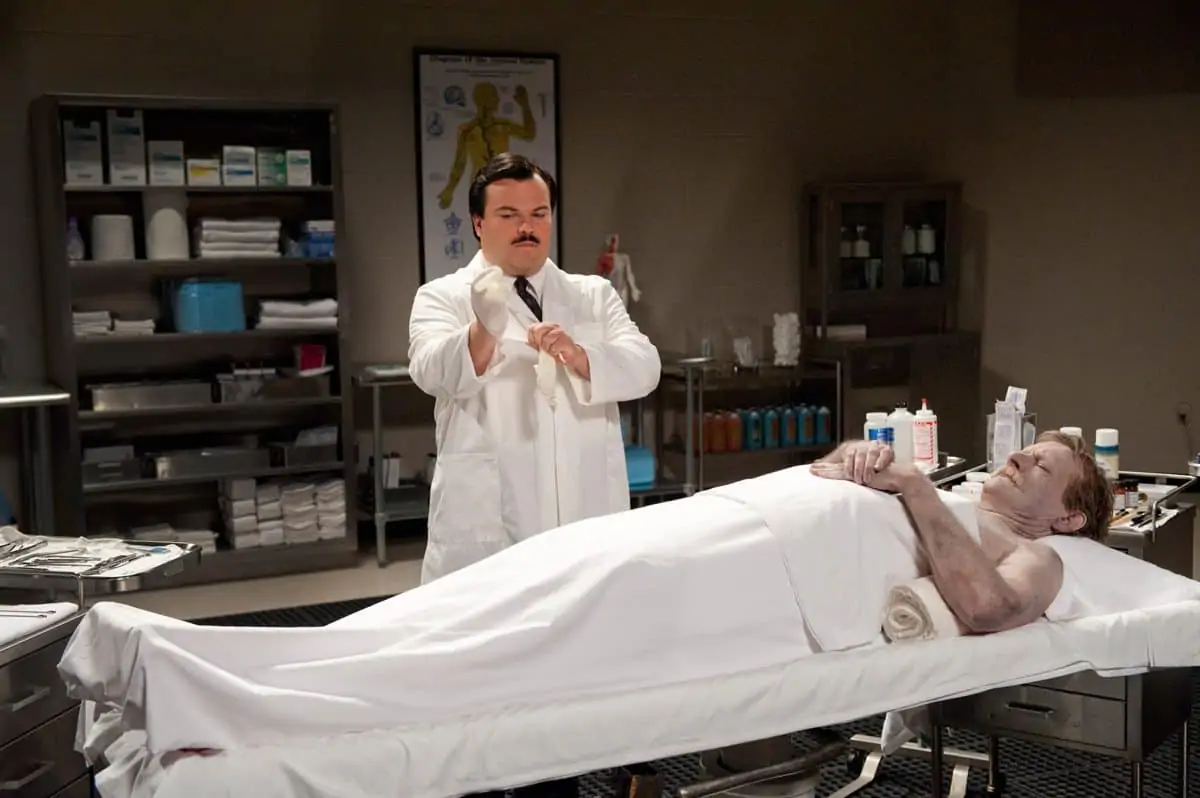

In a small Texas town, the much-loved local mortician strikes up a friendship with a wealthy, but much-loathed, widow. When he kills her he goes to great lengths to create the illusion that she's alive. That’s the premise behind Richard Linklater’s latest movie, Bernie, starring Jack Black and the eponymous hero, and Matthew McConaughey and Shirley MacLaine.

The feature, based on real events in Carthage, Texas, cleverly combines interviews amongst local townspeople as they recount events and elaborate on the characters, with staged scenes with the principal actors.

The $6m production was shot by Dick Pope BSC in and around the town of Bastrop, which doubled for Carthage. It is Pope’s second film with Linklater, the pair having collaborated on the BAFTA- and BIFA-nominated Me And Orson Welles (2008). Unlike, their previous film, Bernie is very much about portraits of the townsfolk, an aspect that typifies much of the work Pope has accomplished with British director Mike Leigh. Bernie was the cinematographer’s first full digital shoot. Ron Prince caught up with him over Skype, to chat about his experiences…

How did you get involved with the production?

Rick had seen my work on Topsy Turvy (1999) and The Illusionist (2007, for which Pope was Oscar-nominated) – both period films and both set in theatres so he asked me to shoot Me And Orson Welles, also largely set within a theatre. I got on great with him, and he must have liked what I gave him as he asked me back to shoot Bernie.

What appealed to you about Bernie?

Firstly, being asked back again by Rick – he is a cool guy to work with. Bernie is a completely different type of film to Me And Orson Welles, and I was attracted by the challenge. I loved the script too. It’s a very affectionate, personal portrait of a small town in Texas, near where Rick lives, and it was his first film with Jack Black since School Of Rock.

It’s also partly in documentary style, which greatly appealed to me, with many portraits of local characters both real and imagined, as witnesses to the events that unfurled. But the clincher was that the film has a big US courtroom scene, which is something I’ve always wanted to shoot.

What research did you do?

The biggest research I did before I arrived in Texas, was to shoot a short film for Mike Leigh in London, called A Running Jump, commissioned for the 2012 Olympics, which I shot using the then very new ARRI Alexa. That was invaluable as a learning curve, as I had hardly shot digital before. This film with Mike, and the extensive testing I did at MovieTech, were ideal for me to get to grips with the camera and the workflow. A Running Jump is a very colorful, quite crazy film, with Eddie Marsan in the lead, that we shot over three weeks. I discovered that the Alexa is quite straightforward and, apart from the electronic viewfinder, offers you a film-friendly experience, and I loved the results. We used the Codex on-board recorder and I knew that the long runs before changes would be invaluable for Rick as he likes to turn and turn without interruption.

When you first discussed the look of Bernie with Richard Linklater, how did you envisage the film?

Intimate and naturalistic, set in a wide variety of locations, building a warm, compelling portrait of Carthage.

What was the working schedule?

Brutal! The shoot was a total of 30 days. We spent around seven days shooting dozens of interviews, each one at a different location, and shot these first. We then had 22 days with the principal actors. Although it was blindingly fast, we mostly managed to keep to five-day weeks with little overtime.

What aspect ratio did you select?

Bernie is not a landscape movie; there are no big Texan vistas. It’s character-driven and so in keeping with the intimate subject matter, I chose to go with 1.85:1.

Can you describe the portraits?

The portraits (or ‘gossips’ as Rick called them) appear throughout the film to flesh out the backstory, and are counterparts to scenes with the principal actors. Most of these feature ordinary towns people who remembered the characters and the events that took place. We shot them at home or in their workplaces, documentary style, and I used a very still, unobtrusive camera, so the audience aren’t sidetracked and can just get to know these folk as they reveal their thoughts and feelings. It’s quiet, observational filmmaking – one of the things I love.

Tell us your reasoning behind your choice of cameras, lenses, film stocks, lights and grip?

Rick already wanted to shoot digitally and I sold him the idea of using the Alexa about six months before we began. But when we finally kicked off there were still only a total of 30 Alexas in the USA and it was all a bit of a struggle. The SxS picture cards we were going to be using only got enabled by ARRI just before we started, and trying to obtain our second camera was interesting. In fact, Steve Speers, my 1st AC, purchased an Alexa, which arrived on the very last day of prep, resulting in much relief all round, particularly on Steve’s face!

For the portrait work we wanted long, uninterrupted takes and the smallest crew and profile as possible to make the subjects feel at ease. The Alexa, with 444 Pro-Res LogC was perfect for that. I used the 18-70 Optimo zoom so we could maintain a very low profile with no fuss concerning lens changes. As Rick conducted the interviews, I used my own judgement as to the framing and size of shot, and used either natural light or very small lighting units powered locally. There was no generator, lighting or grip truck. We kept the gear to an absolute minimum so it would fit into a single van so we could move on to the next location as speedily as possible. However, the main part of the shoot was with big stars and the full ‘movie-comes-to-town’ experience. For this I employed a full grip and electrics package, and used mostly Cooke S4 prime lenses unless we were on a crane.

Where did the kit come from?

Apart from some that Steve Speers supplied, most of the camera gear came out of MSP in Dallas, run by Marc Stephens. The camera situation was a bit of a worry as the Alexa was still so new, but MSP had a great relationship with ARRI and got us our main camera. Their gear was really good.

Was the camera generally on a dolly, handheld or on a Steadicam? The portrait sections were on sticks. On the main shoot there was no Steadicam, a joint decision by Rick and I, and were mostly on a dolly or a hothead on a crane. The only hand-held was where the camera became a TV news-gathering camera with the footage generated onto TV sets.

Did you shoot at practical locations, on sets, or both?

There was no studio work. We shot the entire film at locations, although some sets were built within those locations.

"It’s quiet, observational filmmaking – one of the things I love."

- Dick Pope BSC

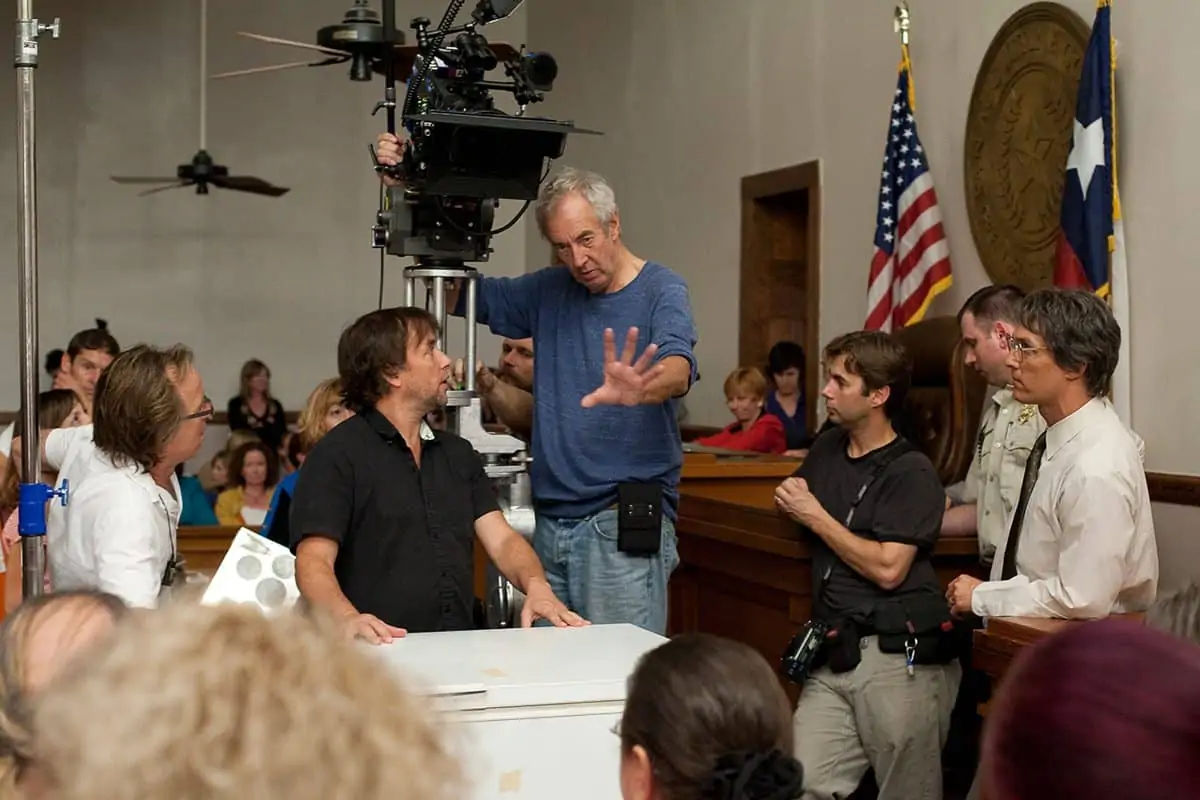

You said always wanted to shoot a US courtroom scene. Tell us how you approached this.

I’m a great fan of courtroom dramas, like 12 Angry Men. For Bernie, I wanted a pretty classical look, a real Southern feel, with slow moves on dollies into the witnesses, the accused, defendants, the judge and his gavel. I love all that, and the process of plotting it out. It’s one of my favourite parts of filmmaking – how to shoot for best emotional effect. In this courthouse to ensure coverage, and to meet the schedule, we shot with two cameras.

For the theatre work in Me And Orson Welles, we had scale models of various sets with actors, and Rick and I would sit there for hours devising how to shoot every set-up. We didn’t go that far on Bernie, but we did talk endlessly in prep and at the location, mapping out exactly what we wanted to do.

The courthouse in Bastrop is wonderful, late 1800’s, built from wood, but it’s at least 30ft up, on a high first storey with bare windows . I couldn’t be at the behest of the sun, and we could have a scaffold rig or cherry picker outside to bring light in through the windows because we were often looking straight out, and weren’t allowed to touch the extensive gardens below. So I asked Bruce Curtis, our very creative production designer to reinstall old-fashioned wooden plantation shutters over the windows. This allowed me to smash 18ks against each window from down below in the gardens. These wooden shutters lit up like they were being blasted by sunlight and I could adjust them to direct the light up onto the ceiling and bounce back into the room. I also had diffusion frames made that could slip onto the windows behind the shutters when we were looking that way. This combination gave me a natural but subdued light. As there were no lights on the floor, we could quickly move the cameras 360 degrees and when the sun went down, no problem.

What were your main concerns during the shoot?

Moving fast to make the days whilst protecting the look, as we had such a tight schedule, with multiple location moves most days. So I had every location as pre-rigged as possible. I was also concerned about using the only recently enabled picture cards as our recording device, but they worked just fine with never a problem.

What part does risk-taking play in your work, if any?

Well, to me, one of the biggest risks I feel I take is jumping on a plane with my meters and flying off alone somewhere to work with what is often a complete bunch of strangers.

Were there any happy accidents, unexpected things that worked out well?

Finishing the film on time!

How was the experience of shooting in Texas?

Fantastic! Austin, what a city. I totally loved it and could have settled there quite happily. I had a great local crew. Mark Manthey, had previously gaffered for Emmanuel Lubezki, on Tree Of Life, also out of Austin and also with minimal equipment and a small crew, so he was the perfect choice for me. My key grip was Marc Andrus, terrific, as was Dustin Cross, our DIT. Dustin is one of America’s top DITs, and it was reassuring to be able to look over his shoulder on set. He even delivered the timed and synched dailies to us on Apple iPads. Brilliant. Steve Speers, my superb 1st AC was not-Austin based, but came down from Minneapolis, where six months before I had worked with him on ‘The Convincer’.

Where did you do the DI?

I graded the film at Deluxe Digital in LA, over the course of ten days, with colorist Kevin O’Connor. One of the great things about shooting digitally is that in the DI suite, once everything is applied correctly, the files transfer and snap-in so consistently well onto the screen – certainly good enough to share with the director and producers from a very early stage.

Will you ever shoot on film again?

Yes definitely. If there’s still celluloid around it would be fun to shoot on film again, but I have not shot any for two years. The commercials have all been on the Alexa too. But I would certainly not write film off. Only a few months ago I was on the main jury at Camerimage, and viewed all 15 films in competition plus quite a few others as well, and got an overall perspective of film and digital side-by-side. It’s not a matter of one versus the other for me, but film has a different look, and it’s very pleasant. Perhaps it’s the grain but, whatever, it looked rather good and made me feel just a little nostalgic.