4K and HDR Restoration

Dean Cundey ASC / Escape from New York

4K and HDR Restoration

Dean Cundey ASC / Escape from New York

BY: Kevin Hilton

In the first of an ongoing series looking at the 4k and HDR restoration of classic films, Kevin Hilton talks to Dean Cundey ASC about shooting John Carpenter's Escape from New York and his involvement in the recent remastered version.

The higher resolution and sheer branding power of 4k has reenergised the film restoration business in the last few years. Directors and cinematographers are often involved in the updated versions to ensure their vision and intention sustains but the success of the whole process relies on the quality of the source material. When it came to restoring John Carpenter's cult classic Escape from New York (1981), director of photography Dean Cundey ASC was pleased to find the film elements had been in decent condition.

"People cared about the movie," he says, "It was in particularly good shape and had been generally well cared for. They went back to the original material; I think they were able to find the original negative because some previous restorations had been done from the inter-positive." The main grade was carried out at L'Immagine Ritrovata lab in Bologna, with a review screening organised for Cundey and Carpenter in the US.

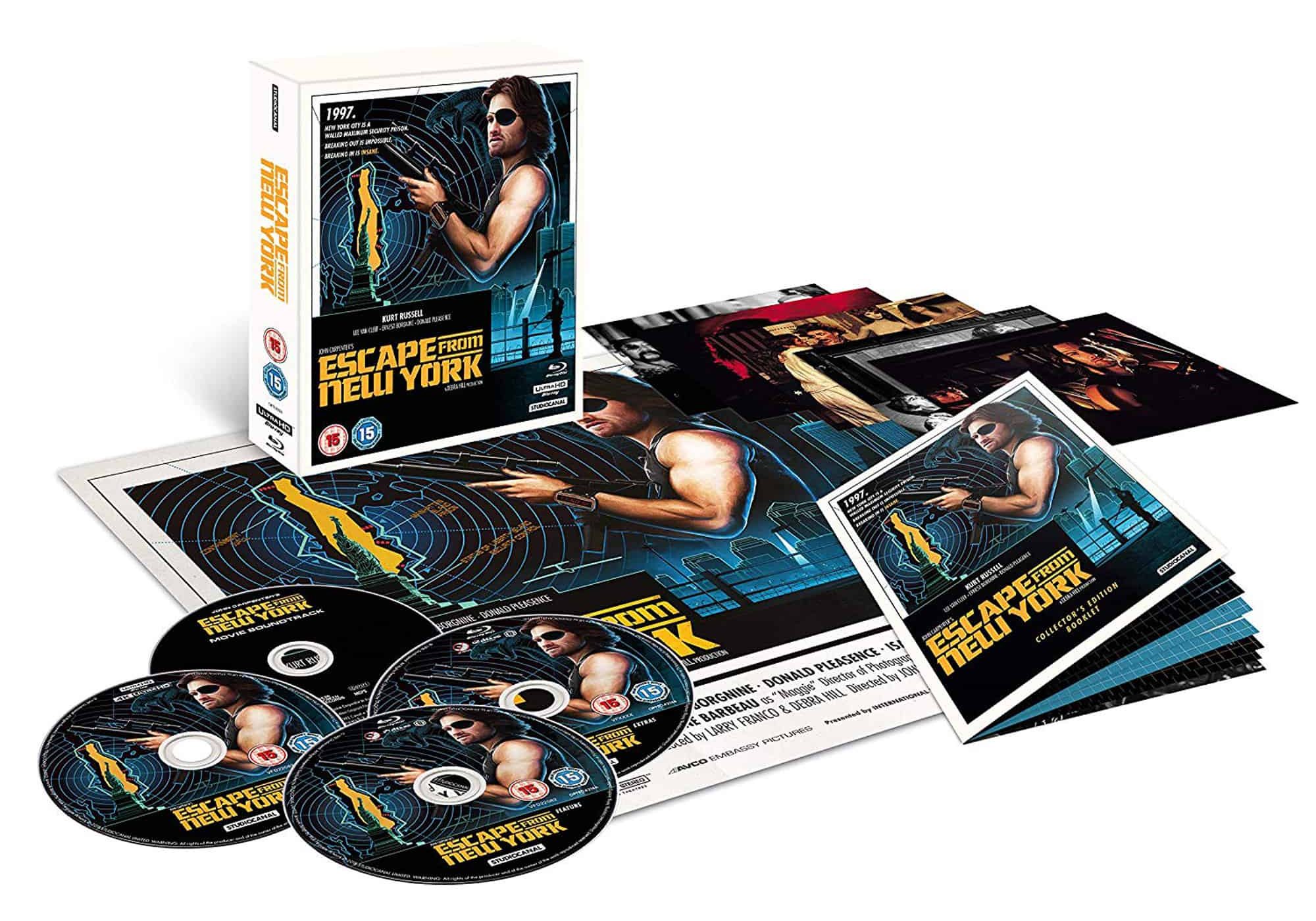

Escape from New York had a short theatrical re-release at the end of last year along with three other restored Carpenter films from the '80s - The Fog (1980), Prince of Darkness (1987) and They Live (1988), the last two shot by Gary B Kibbe ASC - with all four available on Blu-ray Disc. Cundey explains he became involved in the restoration project after a call from Studio Canal, which now owns the rights to the titles.

"They asked if I would be interested in reviewing the restored version, which I was," he says. "I looked at the colour grade with John and we were very pleased to see how bright and back to the original it was. We could interact with it and there were one or two shots I maybe would have changed. In general I was happy with it because nothing had gone astray, which sometimes happens if a colourist has made changes by referring to an old version [instead of the original]."

Cundey shot five films for Carpenter, starting with the horror milestone Halloween (1978), which celebrated its 40th anniversary last year, coinciding with a 'requel' that ignored the previous sequels and picked up 40-years after the original. The Fog and Escape from New York came next, followed by Carpenter's masterpiece, The Thing (1982), and the martial arts fantasy romp Big Trouble in Little China (1986).

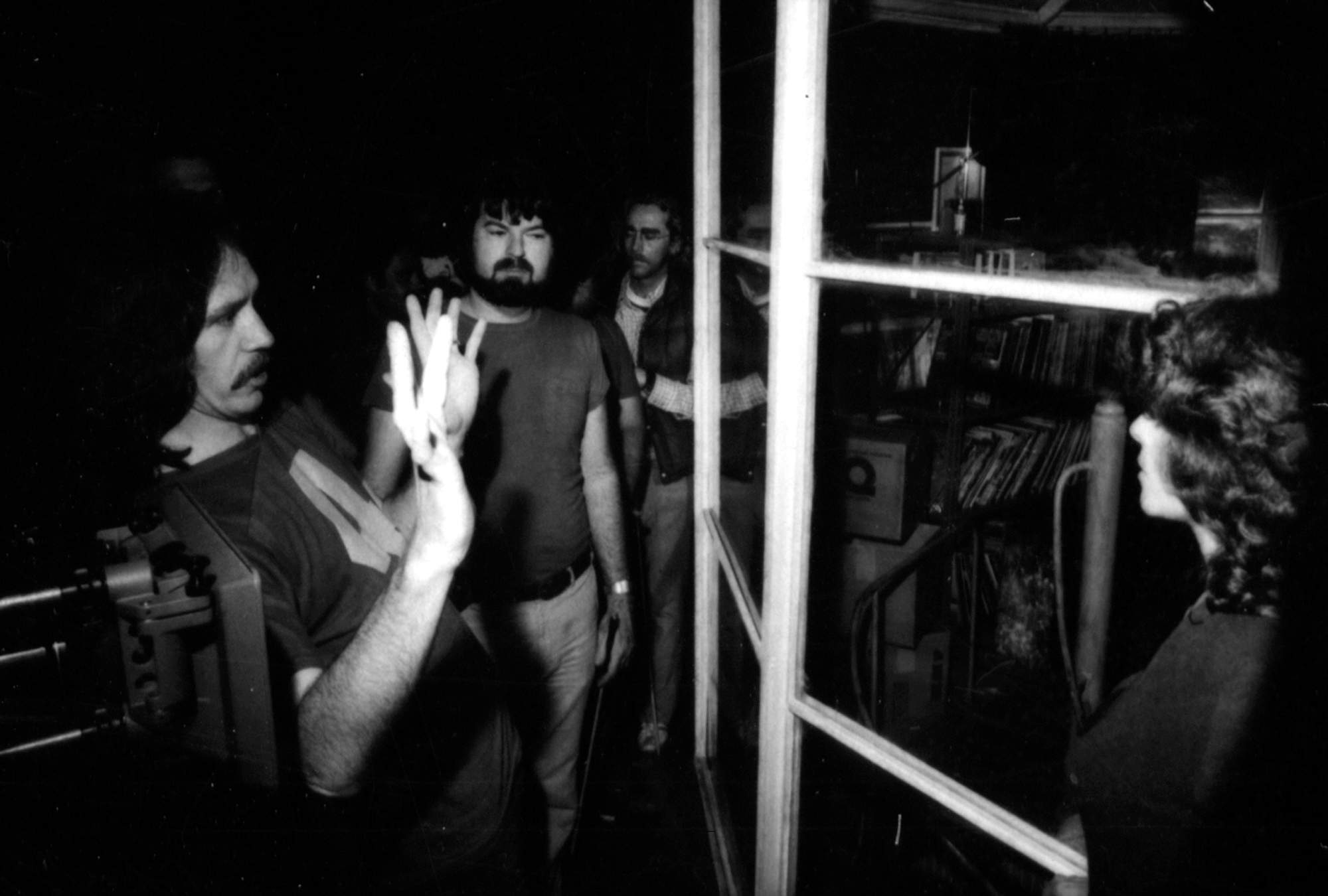

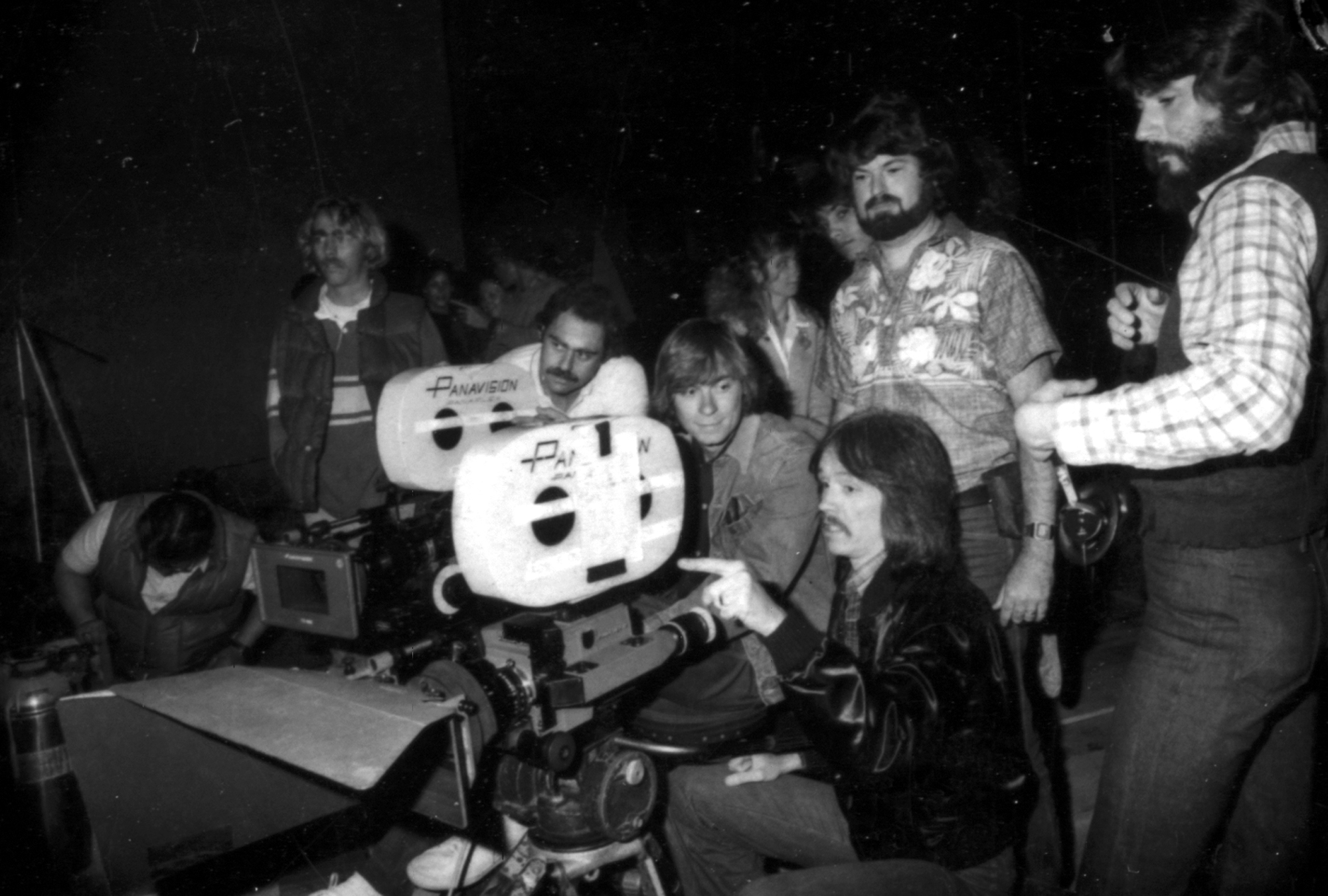

Most of these films had low budgets but Cundey says emerging technologies helped achieve the desired look despite that. "When we made Escape from New York we were at the point where there was new equipment available," he comments. "HMI lights were becoming feasible and Panavision had developed new lenses with the 1.59 T stop, which enabled us to shoot in low light on large expanses of land."

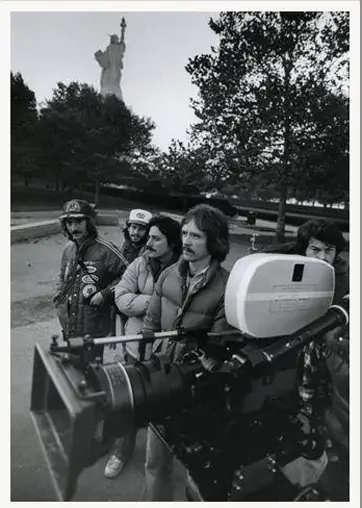

These developments came in useful for Escape for New York, a dystopian action thriller set in the near future with action taking place on a Manhattan Island that has been turned into a self-contained prison. Some scenes were filmed in New York itself, with others in Los Angeles, but the majority of the shoot took place in St Louis. This was partly because several sections of the Missouri city were severely dilapidated at the time and partly because there would have been too many restrictions in New York.

"It would have been impossible to shoot in New York because we couldn't close off streets," Cundey explains. "In St Louis there were five to six square blocks of old buildings that were designated to be torn down and the authorities said, 'Do whatever you want to the streets.' That gave us a great environment in which to shoot because we had the run of the streets and could put lights in buildings."

This urban wasteland was what Cundey describes as the "ideal situation" for a dystopian story, which he says no one else was doing at the time but is more common today. Much of the mood also depends on the production's extensive night time shooting; as Cundey says, the arrival of anti-hero Snake Plissken (Kurt Russell) at the prison processing centre would not have been as effective or interesting if it had taken place during the day: "We knew the film relied on night and darkness."

To achieve some of the action sequences on a tight budget, miniatures and wire-frame animation were used, while the skyline of New York was created through glass matte paintings. "It's very rare or not even done at all these days but I got to experience a technique that was common in the early days of movies," Cundey says.

"When we made Escape from New York we were at the point where there was new equipment available. HMI lights were becoming feasible and Panavision had developed new lenses with the 1.59 T stop, which enabled us to shoot in low light on large expanses of land."

- Dean Cundey ASC

The use of physical special effects typifies much of Carpenter's work and features in many of the films Cundey made with him. "Everything we did on The Fog was real and in front of the camera," he says. "Even for something supernatural and fantastic like that we created the techniques for the camera and it gives a sense of authenticity about it. If you make a film like The Fog you can be tempted to take it in a way that makes it more fantastic but that shows up to the audience it is not believable. We did our best to make it believable."

What is perhaps Cundey's finest collaboration with Carpenter, The Thing, personifies this aim even more completely. Although some stop-motion animation sequences of the shape-shifting creature were created, they were not used. This left the gruesome, body-splitting transformations to be done using prosthetics, models and mechanics. "All the special effects were done on set with real objects and machinery," Cundey says. "We made a big point of trying to do everything practically because there is something about that the audience can believe in. Were it to be done now the audience would sense it was CG and non-existent."

Cundey feels 4k restorations with HDR (high dynamic range) add to the verisimilitude that physical effects can bring to a film in addition to improving the quality and resolution of the overall image. "I very much like 4k," he says. "In a movie that is supposed to be real it [looks] real because you're seeing much more detail. Digital cameras are getting smarter, sharper and better and lenses are being designed and built by computers to get rid of odd artefacts. So when you put a sharp lens on a sharp camera the image is extremely sharp. That's not always desirable because it can show up blemishes on the skin and imperfections in the set design. The irony now is that you can have an extremely expensive, very sharp camera and a very sharp lens but end up degrading the image with a cheap piece of glass in the form of a filter."

Now in his 70s, Cundey continues to work on features and documentaries, with several films either awaiting release, notably the live action fantasy Anastasia, or in pre-production. He observes that these days he is "obligated" to shoot digitally, feeling this way of working has become de facto. "Film itself is a special thing but I have embraced digital," he says. "Everybody can see the shots on set and it allows for more collaboration. Filmmaking has been changing since film evolved into colour and sound. These things are only tools and the intention of any film should be to tell a story and move an audience emotionally. Digital is just a tool as well and most people wouldn't be able to tell you if they were watching something that had been shot digitally or on film."

Dean Cundey is among the most prolific and highly rated cinematographers in US cinema, with other credits including Jurassic Park (1993), the Back to the Future trilogy (1985, 1989, 1990) and What Women Want (2000). He feels his body of work gives him a degree of immortality, with future film fans having the opportunity to discover the films he shot. The 4k/HDR restorations of Escape from New York and The Fog can only encourage that.