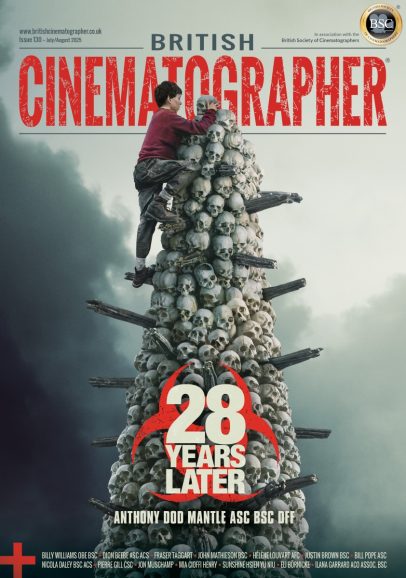

David Heuring: “Nothing Beats The Big Screen”

Mar 15, 2021

NOTHING BEATS THE BIG SCREEN

On 3 December, Warner Bros. announced that its 17 films scheduled for 2021, including Dune and The Matrix 4, would be released simultaneously in theatres and on the company’s streaming service, HBO Max. Jason Kilar, chief executive of WarnerMedia, cast the decision as future-savvy nod to the fans, and necessary, if painful, innovation. Many filmmakers took it personally.

The conflict is of course another example of the eternal tension between the creative minds behind “the liveliest art” and the business side. And with some budgets fast approaching $1 billion, each side needs the other to succeed.

Is the move yet another death knell for the theatrical experience? Will the pandemic, which is accelerating change in so many areas, render the multiplex a sad relic of our “before” lives? I’m not making predictions, but we have heard rumors of demise for 60 years, through the advent of television, VHS, DVD, the evolution of digital technologies, the improvement of the home experience, and yes, streaming. And in a more general way, while the example of the buggy whip can be instructive, many of these changes have brought positive effects along with disruption. I don’t know the number of professional cinematographers in the world today compared to 50 years ago, but I’m confident growth has been exponential. Generally, the quality of the cinematography in dramatic content on streaming services is consistently nothing short of extraordinary. Cinematographers tell me that their opinions and contributions to these projects are valued and respected to a much greater extent than in previous eras of home entertainment. The infrastructure today is capable of delivering and displaying the work of cinematographers with nuance and power exponentially greater than in years past. That can only help the art of cinematography and its practitioners.

But in the world of cinematography, we know that the full power of the medium can only be achieved on the big screen. Spectacle has been a crucial aspect of cinema for more than a century. The social aspect of the theatrical experience can be a joyful enhancement, but we must admit in certain circumstances it can be a detriment. Prior to COVID, the theatre business model was surviving despite good quality big screen entertainment in widespread use at home. Some observers predict a renaissance for theatrical presentation, speculating that once people are again free to safely congregate outside their homes, theatres will be packed.

But spectacle alone does not define cinema. In an essay in the March 2021 issue of Harper’s Magazine, Martin Scorsese bookends heartfelt reminiscences of Fellini films with observations about the nature of cinema, which he contrasts with the notion of mere “content.” He links cinema to artistic creation, emphasising the foment that occurs when filmmakers inspire each other. Scorsese’s opinion is that “the art of cinema is being systematically devalued, sidelined, demeaned, and reduced to its lowest common denominator.”

In a recent tangentially related essay in American Cinematographer, John Bailey ASC wrote of his recent change of heart regarding the future of the cinematic art. Bailey, a recipient of ASC and Camerimage Lifetime honours, and a recent president of Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, noted that since he began as a student projectionist at USC, technology has put the entire surviving history of motion picture art, often pristinely restored, into easy reach. He says that to see the latest VFX blockbuster on the same bill as Paul Wegener’s 1920 film Der Golem is to see “past and present cinema intersect, overlapping in wondrous ways. Who knows where the next generation will take the art, gifted with this inheritance?” Bailey concludes with optimism: “So, a pox on the dystopian vision of cinema’s future.”

In ethical terms, the question of the Warner-HBO Max decision remains. We in North America have long been envious of the rights of the artist in Europe. Hollywood’s violent labour history in the 1930s can be seen as an early manifestation of this struggle for respect in the US In the 1990s, the ASC and the DGA were deeply involved with the Artists Rights Foundation, which was formed to win consideration for the actual makers of films. Today, IMAGO addresses these issues regularly. In fact, one of the central reasons for the formation of IMAGO was solidarity and the power of speaking with a unified voice in such matters. A century ago, the ASC was founded in part as a way for cinematographers to share information, to solve common problems, and to defend the prerogatives of the cinematographer with loyalty. In 1949, the BSC was formed along similar lines, with one objective being “To further the application of the highest standards in the craft of Motion Picture Photography.”

These noble goals must be continually sought after by all of us who love cinematography, at every opportunity. In his Harper’s essay, Scorsese says, “We can’t depend on the movie business, such as it is, to take care of cinema… Those of us who know the cinema and its history have to share our love and our knowledge with as many people as possible. And we have to make it crystal clear to the current legal owners of these films that they amount to much, much more than mere property to be exploited and then locked away. They are among the greatest treasures of our culture, and they must be treated accordingly.”

BY: DAVID HEURING

(Photo by Yousef Linjawi)