FIGHTS, CAMERA, ACTION

Boasting slick and mind-boggling stunts, technical prowess, and a distinct style, the hit John Wick franchise has dared to be different. With Chapter 4 the filmmakers endeavoured to elevate the action whilst taking the story to new global and artistic territories.

As a new chapter begins in the action-packed world of hit man John Wick, the imaginative minds behind the fast-paced franchise wanted to take their latest creation in a visually adventurous new direction to expand the bold and brave Wick universe. Chapter 4 sees Keanu Reeves return to lead the action on a quest around the globe to defeat The High Table council of crime lords and tackle powerful assassins of the underworld.

Chad Stahelski, who directed and produced the previous trio of films, is at the helm and his martial arts background continues to impact the slick and expertly choreographed action and stunt sequences at the films’ core. Having entered the field aged 24 as Brandon Lee’s stunt double in The Crow, Stahelski went on to double for Reeves in The Matrix among others before moving on to fight choreography, stunt coordinating and second unit directing and launching his own production company.

“We didn’t want each film to just be bigger than the previous one,” says Stahelski of Chapter 4. “We wanted each to expand on the character and his world. To be better, as well as bigger.”

Reeves, who also serves as executive producer on the film and was in every script meeting and casting discussion, believes the film has “a look and scale unlike anything we’ve seen before. There are no less than 14 major action sequences, including a wild and epic chase through the streets of Paris.”

Having shot the second and third John Wick films, when exploring the fourth’s visual approach, cinematographer Dan Laustsen ASC DFF (The Shape of Water, Nightmare Alley, Silent Hill) agreed with Stahelski it should be “even more powerful and creative, and with even more stunts”.

“Chad was happy with the third movie but wondered if it was the furthest we could go,” says Laustsen. “So, we talked about making the colour palette stronger and looked at where to shoot that fitted with our ambition to be bigger and more beautiful.”

While the second and third films were shot in New York, Stahelski wanted to expand the vision by looking for suitable European cities, leading him to shoot predominantly in Berlin and Paris with additional scenes in Jordan and small sequences in Japan and New York. While the camera and lighting crew key positions largely remained the same in all locations, the grip team changed in Berlin and Paris, and Laustsen was not at the Japan and New York shoots due to filming The Color Purple.

“Chad is keen to film everything on location and it was great to shoot in multiple places but changing location frequently could be challenging as we had a relatively short time in each, but the crew was exceptional at every step,” adds Laustsen.

Creative inspiration was found before the fourth film was a certainty, when Stahelski and Reeves invited Laustsen to join them on a promotional tour for Chapter 3 in Japan. “It was my first time in Japan, and and the colour palette of Chapter 4 started on that trip as we walked around Tokyo and other cities. We were influenced by the strong colours and deep blacks which we later discussed with production designer Kevin Kavanaugh (Only the Brave, Nightcrawler, The Dark Knight Rises) who we worked with on the previous two John Wick films.”

Despite Laustsen being a fan of steel blue, it did not feel like a strong enough colour. In line with the ambition for a bold palette the filmmakers predominantly worked with colours they called Berlin Red and Chad Green.

“We’d seen the neon sign version of Japan depicted many times, but we wanted to go in a different direction. That’s the beauty of John Wick – a colour palette we haven’t seen too often,” says Laustsen, who does not work with a LUT and mainly adjusted the saturation and black for the film. “It’s important our dailies and what we shoot on the day is the way the final movie looks.”

New lensing frontiers

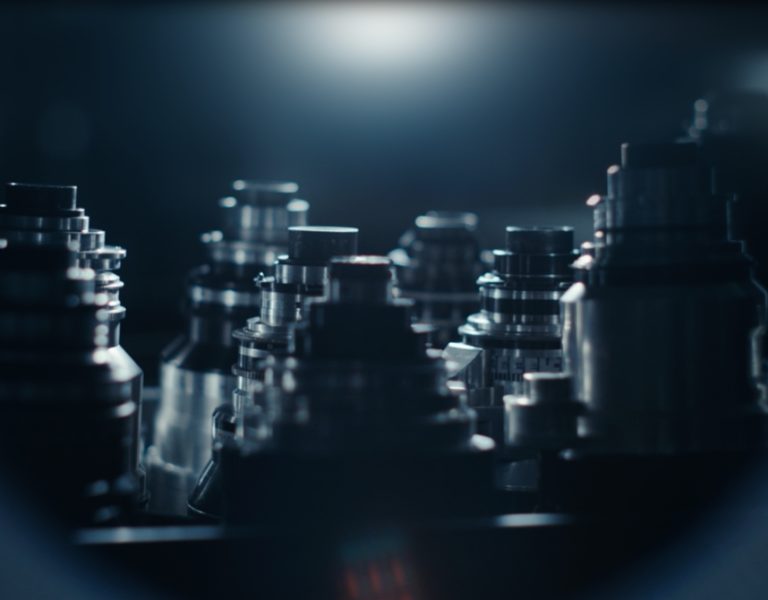

The latest film transitioned from Super 35 to Large Format, shooting with ARRI’s Alexa LF. Having filmed the second and third instalments on ARRI Master Anamorphic prime lenses, Laustsen and Stahelski agreed to shoot anamorphic again but also wanted to explore a new visual approach.

“I’d heard ARRI was making a new set of anamorphic lenses – the ALFAs (ARRI Large Format Anamorphic) – which had been used on The Batman. When we carried out tests with the helpful ARRI Berlin team, we fell in love with the new lenses’ fall off and the lack of depth of field on the long lenses,” says Laustsen.

“We shot T4 all the time, often using wider angles and long lenses and not using the middle part of the lenses much, so the ALFAs were perfect. We also shot a couple of tests with Signature Primes for a reference of how sharp we wanted it to be, but the ALFAs were clear winners and used for 95% of the movie.”

Laustsen also consulted focus puller, Doug Lavender, who he has worked with since collaborating on Nightmare Alley in 2020 and refers to as “a camera equipment expert.” During prep Lavender ensured the cameras and lenses worked as they should, and he remained flexible during filming to adapt to changing environments.

“I happily rebuild the camera many times a day to fit its intended environment and anticipate what will slow down my work, so I’m ready to reduce, protect and modify the gear for each new challenge,” says Lavender.

While in the past a movie could be Large Format or Anamorphic, now there are both in the ALFA lenses used on the ARRI LF sensor, he highlights. And as anamorphic lenses do not focus as close as spherical lenses, he used diopters to bring the focus closer when Laustsen wanted a very large close-up or super close detail. “The ALFAs look so great on big close-ups of faces and many of the close-ups were shot with wide lenses very close,” says Lavender. The bokeh highlights look so nice and is very important for this style of movie which features great looking practical lighting.”

Focus pulling on fast action demands Lavender watch the performers and camera move in real time rather than on a monitor, as “what you see in the monitor has already happened and focus will be late.” As John Wick movies are tightly crafted, there are no excess shots or coverage in scenes. “Every moment must be in focus, even in super-fast action coverage. It’s a lot of pressure but satisfying to be part of,” continues Lavender, who is a believer in not blaming the environment for what could have been solved by pre planning a solution.

Alive with the action

Five stunt coordinators and fight choreographers, led by Scott Rogers, oversaw 14 action sequences – four times that of the previous John Wick films. Stunt teams from Japan, France, Bulgaria, Germany, and the United States who spent months perfecting and safely handling the unprecedented scope and scale of action.

An extended fight sequence that moves between multiple levels and spaces of the Osaka Continental hotel, required more than 50 stunt performers to film for almost a month. Adding to his three decades of fight training, Reeves completed eight months of film-specific training, perfecting his judo and jujitsu skills, and being trained in precision driving and horseback riding.

Laustsen wanted to shoot Reeves and the stunt artists as wide as possible – cutting in for inserts. “It feels like a ballet because it’s so smooth,” he says. “I’ve never worked with a master in blocking like Chad due to his stunt background. He knows exactly what he wants. You also have two or three takes with Keanu because he’s so good, so you must be prepared to capture it.”

Laustsen applauds British camera/Steadicam operator James Frater ACO SOC for his skill when capturing the action, including many long takes demanding a lot of Steadicam. “As well as going wider, Laustsen and Stahelski wanted to shoot even longer takes compared to the previous two films because it aligned with the storytelling and stunt rehearsals.

As Laustsen and Stahelski like to move the camera, believing “it should be alive”, it was often on a dolly stabilised head or a crane. “Some scenes we thought might be shot on a dolly, were captured using Steadicam because James is such a master and it’s much faster. When you’re shooting a ballet of a fight sequence it’s more flexible when you don’t have to put a dancefloor down,” says Laustsen.

Frater enjoyed how collaborative and open to suggestions Stahelski and Laustsen were when making creative and technical choices. “The camera moves a lot, especially in the action scenes as Chad doesn’t shoot action in the conventional way. He lets the action play out in long poetic shots that show the choreography and stunts,” says Frater.

“They know what they want from the camera and exactly where to place it to get the most out of the lighting, stunts, and narrative which made mine and the other operator Oliver Cary’s jobs so much easier.”

Having the lead actor perform most of his stunts added more pressure for the camera operator as “nobody wants to be the one responsible for making Keanu do the shot over and over again.”

Rarely were scenes captured with more than two cameras as every shot was meticulously planned, leaving no need for additional cameras for action scenes. “We used every bit of equipment you can imagine – Technocrane, Steadicam, cable cam, Spidercam, drone. Most of my work was done on the MK-V AR Steadicam, especially the fight scenes. This gave Dan and Chad the flexibility of moving the camera quickly and still feeling stabilised, allowing the action to play out within the frame,” continues Frater.

“Some sequences we’d shoot for weeks, and I’d be on Steadicam all night. I love it though. The biggest challenge is the 18 weeks of night shoots – there’s not much that can prepare you for that.”

Different approaches to framing and movement were adopted for certain characters. Caine (Donnie Yen) – a blind martial artist and Wick’s long-time friend who must turn against him when The High Table threatens a family member – was captured in a calmer way and using more classic compositions whereas more movement was used when shooting Wick.

Space to perform

As the film mainly takes place at night, all lighting fixtures needed to be dimmable for fast adjustments. Following discussions with gaffer and chief lighting technician, Helmut Prein, predominantly LED fixtures were chosen aside from for some larger set-ups in Paris which relied more on ARRI T24 and T12 as Dino lights.

“Dan likes to tweak levels of lights precisely to the image, so every unit was controlled by board operator Anton Meister,” says Prein. “After testing, we chose Creamsource Vortex8s as we faced locations with lots of humidity or lengthy exposure to unpredictable weather conditions outdoors.”

The Vortex is IP 65 – water resistant and sealed - and withstood all weather conditions including when a rig of 30 units were left out in a heavy downpour for three weeks. Prein prizes their ruggedness, colour rendering, control options, and impressive throw of light when used without a diffusion screen. The fixture became the workhorse fixture and despite their popularity the number needed was sourced with the help of MBS UK via ARRI Rental Berlin.

Astera Titan tubes were also heavily used, again offering impressive colours and dimming options and Laustsen suggested using Kino Flo FreeStyle for its colour rendering and skin tones.

As well as a shared taste in colour and exposure – preferring deep blacks – Laustsen and Stahelski are fans of single source lighting. “Dan and I tried to develop a special look for each location,” adds Prein. “Pre-lighting sets became our weekend sport and was very helpful.”

Due to the fast-moving action and to allow performers space and flexibility, lighting needed to be far away, and fixtures could not be placed on the floor. As practical light was also crucial, Prein and the set design team collaborated to choose the best design elements. “Sometimes it might need to be designed by the art department,” he says. “Nowadays it will mostly be LED for its controllability and on Chapter 4 we used mainly 5-6 Colour LEDs.”

Red/Green/Blue/Amber/White was the lighting team’s favourite alongside the special tones of Berlin Rust and Chad Green as key colours for Berlin night lights. For Paris, #117 Steel Blue and 2800° Kelvin Tungsten was the main colour and hundreds of Titan tubes were often used as practicals inside fluorescent housings.

Laustsen also introduced Prein to the “game changing” Riedel Bolero intercom system which offered him, Laustsen, and board operator Meister an exclusive channel.

Ambitious action

Many locations were selected by Stahelski before Laustsen came on aboard, including the space used for the ambitious nightclub sequence where a battle between Wick and Killa (Scott Adkins) takes place and which saw 200 extras, 35 stunt performers, waterfalls, and complex lighting design unite over two weeks of filming.

The Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin served as the exterior of the nightclub and for the interiors the filmmakers built the largest multi-storey set of all the John Wick films featuring extensive practical water and fire effects inside the partially open interior of the three-storey Kraftwerks Building.

The scene was unlike anything Laustsen had worked on, requiring extensive pre lighting of the 400-metre-long, 60-metre-high space and again incorporating strong red and green tones.

“That’s what I love about Chad – he had the idea to shoot a crazy action sequence in a club in water and made it happen with his crew,” says Laustsen. “Doug, James, Helmut and I looked at how best to shoot and light a big stunt scene in those conditions and go as big as we could while making sure everything was waterproof against thousands of gallons of water pulsating from the ceilings.”

Months before filming began, Laustsen sent Lavender a video of a water test in the night club set and in prep the focus puller tested Hydroflex camera bags that could either be handheld or on a Hydrahead on a waterproof camera crane. To keep the lenses clear of water and the cameras cool they used compressed air tanks and hoses to constantly blast air into the housings while shooting.

“I had 40 filled air tanks delivered to set each night for the nine nights we shot the scene,” he says. “It was a sensory overload; much more difficult when you are tasked with keeping images in focus and cameras dry and fog free! It all worked very well but it was a true camera assisting challenge.”

Protecting the cameras in scuba bags also made them heavy and awkward for Frater to use handheld. “We used two cameras either handheld in scuba bags while near the water, on a Chapman/Leonard hydroscope crane or Steadicam AR in the dryer parts of the location,” he adds.

Little haze or atmosphere featured in the film as Laustsen wanted the black to remain pitch black rather than grey. “In the nightclub we used a lot of water mist and steam because steam disappears in a subtle way rather than building, and you seeing the source and it then disappearing,” he says.

On the upper level of the club, the sun needed to be in shot which Prein and Laustsen created using a rig of 85 Vortex8s. “The set decorators put underwater LED ribbons everywhere and Gerd Nefzer and his SFX crew built a water system in the set pumping out 1,000 litres per second,” says Prein.

130 directional battery-operated and IP 65 water resistant Cameo Zenit 200 LED units were used in strobe mode to light the crowd in the waterfall section. Many Robe Pointe moving heads created beam effects when Wick fights his way through the crowd along with many more Vortexes hung from ceiling beams and six T12 side lighting the first section when the camera enters the main hall.

“As the cherry on the cake, we had a circular 3m rig of 12 Robe Pointes cutting through the waterfalls. It was crazy fun,” says Prein, who thanks rigging gaffer Roland Patzelt, rigging key grip Christian Brubach and their crew for helping create those scenes. Adding the additional effects and extensions was complex for visual effects supervisor Jonathan Rothbart and his team, as lights “were spinning in perpetual motion and coming from different sources in different directions.”

Dramatic lighting

Visual ambitions remained high when shooting an extended fight sequence in the Osaka Continental where gun fight action unfolds in an exhibition room filled with illuminated fluorescent glass display cases. Kavanaugh found the perfect solution from lighting design company from Paris, but as not enough were available the team constructed additional units using 8-foot Astera Hyperion tubes.

The filmmakers wanted to create a feeling of unease through the lighting as they also did in a poker game scene in Killa’s lair. Laustsen wanted the light “to be part of the drama and a third dimension in the atmosphere of the scene.”

Initially the poker game – which is held in a secret space beneath the nightclub – was planned to be shot in a small clubhouse, but shortly before shooting the filmmakers switched to a more suitable 50-metre-high space above the main nightclub location. Two cameras on dollies captured the scenes before Steadicam AR and handheld when the fighting breaks out.

“We completely changed the approach, so instead of going small in a hidden space, we shot in this huge place with powerful red lights and moving head fixtures behind Killa,” says Laustsen. “It’s great when you discuss with the director and production designer and change direction.”

Three vents were lit by Elation Proteus Maximus moving lights, creating an effect which Prein likens to sword blades cutting through the room and actors, combined with a “circular accumulation of pin sharp light beams pointing to Killa`s seat and heating up the atmosphere.”

When the action moves to a forest in Japan at night, the crew recreated the feeling of Japan on a backlot in Berlin working with a green and rusty red concept based on many lanterns and key lights. “Like every time we moved to a new set, a lot of time was spent pre lighting in close collaboration with the lighting and camera crew and DITs,” says Laustsen.

“There’s a thin line between beautiful and cheesy. At first, we didn’t think there should be much green in the forest scene, and it should be warmer, but it was getting too romantic, so we decided a strong green contrast colour was best alongside the red. Those colour palettes are so sensitive to exposure – if you go a little too dark or bright, the colour changes drastically.”

Fight or flight

As Wick continues his race to Sacré Coeur for a duel with the Marquis (Bill Skarsgård), he encounters assassins determined to kill him as he attempts to climb a seemingly endless staircase and falls multiple times.

“We did one of the world’s longest stair falls down all 300 steps,” says US stunt coordinator Stephen Dunlevy. “It’s a steep staircase with railings down the middle, drop offs on one side, and ramps with trees on the other side; there was so much to play with stunt-wise.”

Filmed at Rue Foyatier in Montmartre, Paris, over 10 days, capturing the lengthy tumble down the flight of stairs relied on cable suspended Spidercam that follows Wick in a oner from top to bottom and Steadicam operated by Frater. Two cameras were used for going up the stairs – mostly Steadicam AR and handheld. A cable cam tracked in front of Wick as he falls all the way to the bottom.

Little handheld was used throughout the movie as the filmmakers did not find it suited fights played as wide as possible. Mostly A cam was on a dolly and B cam was on Steadicam, but as select sequences such as the stair fall were difficult to shoot and left little space for a dolly, some was shot with handheld and Steadicam simultaneously.

“As a film crew, we had to walk up and down the 222 stairs leading up to Sacré Coeur Bascilica with our equipment many times a night,” says Lavender. “We shot most of the stair scenes in sequence, meaning fighting our way up, following our characters down and fighting back up again. I tried to keep the package a bit smaller for these weeks, but we still needed all our prime lenses, batteries, and support gear.”

(Credit: Murray Close/©2023 Lionsgate)

It was also difficult to light such a large area in the middle of Paris and required Prein’s team to find rooftops where they could place four ARRI T12 backlights on the scenery. “We realised the lights just worked for the first section of stairs,” says the gaffer. “Climbing up the stairs, we found two lanes on the left in which we could place two cherry pickers with two ARRI T12s on Max movers on each.”

At the top of Montmartre, they placed another Condor with two ARRI T24s on remotes and all fresnels were gelled with #117 Steel Blue. “On every roof we could access we parked four to six Vortexes on stands to fill in the darker sections,” he adds. “For the actors we used mainly Kino Flo Selects and handheld Astera Titan tubes were useful for the action sequences.”

As the existing lights were not suitable, they were switched off and the team investigated units which could be photographed without looking like film lights. “The space in the street lanterns was very tight but we managed to install three Astera AX3 Lightdrops in each and hard-wired them to the existing powerline of the lanterns, allowing control of the street lanterns through our dimmer board.”

Need for speed

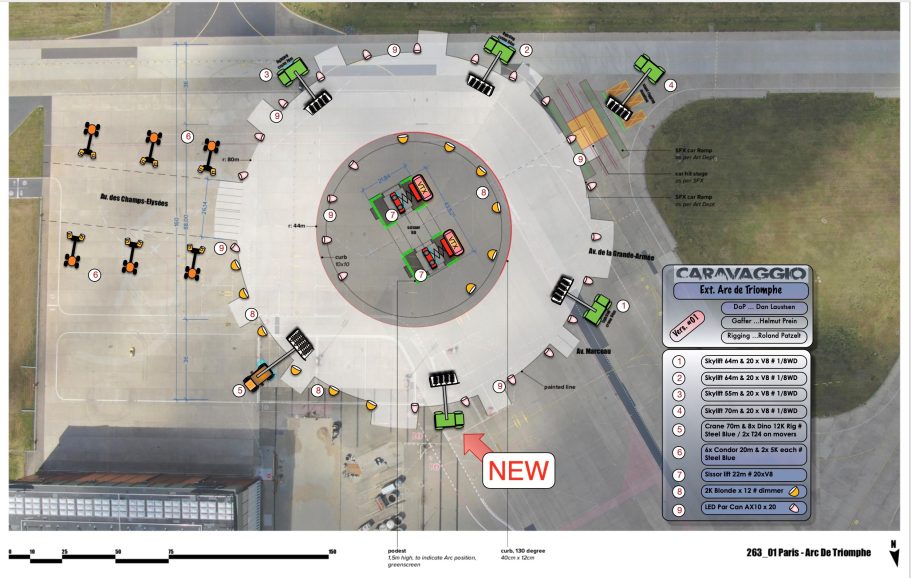

As if water-drenched nightclub fight scenes, and endless stair tumbles were not ambitious enough, the filmmakers added a high-speed car chase into the mix. Culminating in a gun fight in the middle of the traffic circle around the Arc de Triomphe, the scene sees Wick drive a muscle car across Paris, avoiding a raft of killers’ attempts to hunt him down.

Much of the chase – which involved close quarter combat with guns in the street among multiple racing vehicles moving at top speed – was captured at a non-operational airport in Berlin, as it was not practical to close eight lanes of the roundabout for several weeks.

“We did the wire work on the tarmac, and gunfights and judo through several lanes of traffic,” says Reeves. “We’ve had gun-fu in the previous films, and now we have car-fu.”

It was one of the few sequences requiring an additional camera. A drone team was the primary camera for the car chase portion of the sequence, while operator Oliver Cary was in the pursuit vehicle and Frater was either handheld inside the vehicle with Reeves or on Steadicam while he moved around shooting the assassins. Once out of the vehicles they were back into two camera modes, mainly on Steadicam AR, stabilised head on a dolly or handheld.

Lavender believes the scene is a mini movie in itself: “This is one of the craziest traffic circles in the world and to replicate the mayhem took two weeks of night shooting. At least the set was level and smooth and we could roll my camera cart with the various camera builds from one set-up to the next.

“We had a drone team, pursuit car with remote arm and head, used Steadicam, handheld and dollies on track. It was difficult to keep track where we were in the shooting sequence because of the massive volume of shots and constantly moving choreographed driving. “

The sequences had to be lit far away to allow for 360-degree shooting, 20 cars and a drone. Traffic lanes were marked on the airfield for orientation of the stunt drivers and two scissor lifts were installed in the middle of the roundabout to represent the Arc de Triomphe. Both lifts carried 20 Creamsource Vortex8 in each bucket facing towards the circle.

“To mark out the roundabout we spread out 20 Astera AX10 LED pars on the ground of the inner and outer ring. 12 2K Blondes on floor stands created highlights around the lane leading into the roundabout,” explains Prein.

The hero section for the fighting sequence was lit by four Condor lifts – around 50m in height – with rigs carrying 20 Vortex8 each. Three more 70m Condors rounded up the circle carrying the same Vortex rigs, and on the road leading to the Arc de Triomphe there were six cherry pickers, each with two 5K Tungsten as street lanterns. A 70m crane with eight 12K Dinos gelled with #117 Steel Blue and two ARRI T24 provided backlight deep in the back on the driving sequences.

In contrast to the rest of the film, the Arc de Triomphe action adopted a more naturalistic visual approach without a strong colour palette. “We were afraid the scene would become too crazy and confusing for the audience with all the cars and car lights,” adds Laustsen. “Chad’s close collaboration with visual effects supervisors Jonathan Rothbart and Janelle Croshaw and their team was also integral to realising the vision as the footage was rotoscoped and added to the plates of the Arc de Triomphe.”

Sunrise shootout

When elevating the action and visuals, achieving ever more demanding scenes with skill and precision, one of the most difficult for Laustsen was the final sequence – a sunrise shootout between Wick and Marquis at Sacré-Cœur in Paris. For the climactic duel, Stahelski chose to reduce the pace and let tension and anticipation set the tone.

“We needed to shoot that night for day as the only way we could control the sunrise was by hanging many Vortexes on a big rig above the church. We then used a large crane with 4 16K Dinos with full CTO on to create the sunrise as it was slowly lifted and then the visual effects team helped with the background,” says Laustsen. “I’d never done anything like that before. I don’t think many have – it was such a crazy idea.”

The weight of the rig containing 65 Vortex8 for ambient skylight presented a challenge to Prein and his team when flying the rig above the stairs in front of the church. With the help of gaffer Stéphane Bourgoin and rigging gaffer Simon Bérard and their teams the vision was realised.

Chapter 4 plays out in many expansive spaces including a large church requiring an equally gigantic lighting set-up comprising 20 20Ks outside the windows, Vortexes inside and many candles. It was one of the more conventional scenes in terms of shooting, using two cameras – one on a Technocrane or dolly and the other on a dolly.

“The church was a lot of work, but I’ve done that type of scene before and had a clear feeling about what I wanted to do. However, the end sequence at sunrise was more of an unknown,” says Laustsen. “That’s great because you must push yourself all the time which we did through the specialised and consistent colour palette and trying to maintain a feeling of constant momentum.”

Visiting multiple locations also saw the filmmakers shoot in spaces with restrictions such as a scene in The Louvre which they were only allowed to light with LEDs. Creating the sunset feeling in the museum Laustsen wanted demanded many Sputnik lights. “The many other big set-ups included lighting 2km of underground canal in Paris for the Bowery King set which needed lengthy and involved pre lights, and we shot in for around five hours. We spent two days lighting the church sequence for a four-hour shoot.”

Feel the movement

Laustsen was delighted to once again work with Company 3 senior colourist Jill Bogdanowicz (Joker, Thor: Love and Thunder, Spider-Man: No Way Home) who has handled grading duties since Chapter 2. “She’s a fantastic colourist, and it’s great Chad is a director who gets so involved and was in the DI every day,” says the cinematographer.

“Once we choose the colour palette and shoot the movie, the colourist plays an important role in supporting that look. When working with very strong and defined colours you don’t want to change the original concept because then you change everything, the wardrobe, the skin tones.”

Bogdanowicz says of Chapter 4, “we went bolder, with deeper blacks and really strong colour separation.” The essential colour themes, inspired by the key locations, were Paris – “filled with a lot of red, gold, green and some blues,” – and Japan – “which automatically comes up with more pinks, blues and reds.”

Bogdanowicz found the imagery brought enormous richness to the “neg” and used DaVinci Resolve to take the lush photography even further. In the nighttime scene in a cherry blossom-filled forest, the filmmakers, she recalls, “wanted to see and feel the reds and the pinks in the cherry blossoms, while keeping the surrounding blues and greens strong. So, I used a lot of keys and power windows to enhance all the colours even further.”

When colouring scenes filled with fast cuts and rapid-fire action, Bogdanowicz generally pushes colour and contrast further and uses more secondaries to isolate specific elements in the frame than she would otherwise. “You want to make sure the audience really feels the movement and catches the details when everything is going by so quickly. We’d use contrast and power windows to accentuate and shape details, so we could help direct the viewer’s eye, so they don’t miss a sword or a gun or some specific movement in a complex fight scene. Essentially, we’re not just augmenting the colour, we’re using colour to accentuate the choreography.”

Following the action

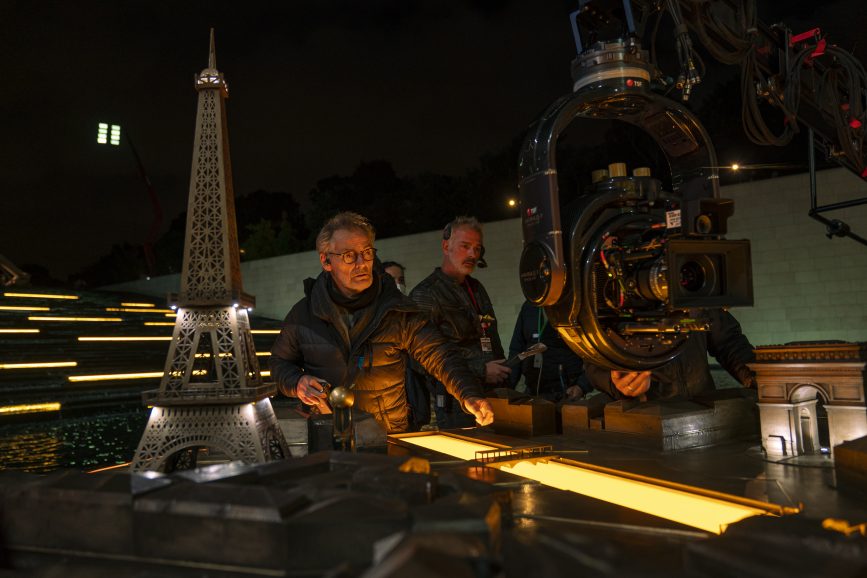

Keen to make this chapter of Wick’s story shine, Stahelski suggested an unusual approach to capture a large-scale action set piece in a French apartment building. The director wanted to adopt a top-down God’s eye view, as Wick enters the building from the street and moves from room to room fending off the enemy in a gun fight followed in an almost video game-like style.

Discussions about the approach involved debate over whether the top of the set should be seen. “We decided that the scene is so unusual the audience wouldn’t mind seeing the top of the set,” says Laustsen. “Chad wanted to have as big a set as possible in a space large enough for the characters to get lost in, so production designer Kevin built all the way out to the walls, leaving little space for lights.”

Kavanaugh designed a space of around 400 square metres which filled one of the stages at Studio Babelsberg in Germany. “Following an involved pre light, we lit ARRI T24Ks and T12Ks with 117 steel blue and the rest of the set was lit using Vortexes and rigs with 12 AX10s to create a flickering light that looks like there’s a neon sign outside the windows,” says Laustsen. “It was filmed over a day and a half – so it was pretty fast shooting – and in one continuous take but then we did a couple of inserts cutting down to some ground fights and then back to the same top shot action.”

The shot was prepped and rehearsed for weeks with the stunt unit and Reeves before stunt coordinator Scott Rodgers plotted the camera move with the Spidercam team. The crew shot it in the Berlin studio using a complex cable cam rig and the interior battles on various floors were then shot by Oliver Cary in an abandoned hospital outside Berlin.

“The scene is one we kept coming back to during the shoot,” says Lavender. “And we always shot at night, even interiors, because we could not black out the sun and have the lighting far enough from the windows to work.”

From multi-level gun fights through to extraordinary car stunts, safety reigned supreme. “Special effects supervisor Gerd Nefzer and his team are so professional and it’s always safety first for Chad, so you feel confident in the cast and crew’s protection throughout filming,” says Laustsen.

“Keanu and Chad are also some of the best shooters in the world when it comes to action scenes and the way they handle weapons is unbelievable. As there have been accidents on sets with guns, Chad worked with an incredible team to guarantee safety was at the forefront.”

For Laustsen, part of the beauty of filmmaking is the teamwork that helps realise the creative vision. “I’ve always loved that about moviemaking, but it gets stronger with each production as you make a film as a team with people who have a passion for what they do.

“I’d be nothing without my crew and that’s important when you’re working with different people – apart from 1st AC Doug who I’ve collaborated with for a few years. Otherwise, I’m working with gaffers, grips, and teams all around the world. I like that system – even if it can be more work adapting each time – because there are so many incredible crews in each country.”