Home » Features » Opinion » President's Perspective »

BSC President Christopher Ross takes a trip into the fascinating world of AI image generation, at the nexus of creativity and technology.

Creation

/krɪˈeɪʃn/

noun

- the action or process of bringing something into existence, of creating something

“The attendees were thrilled by the photographer’s latest artistic creation.”

- the creating of the universe, especially when regarded as an act of God.

“The Big Bang was the moment of the Creation, and therefore the work of God.”

As 2022 draws to a close, so begins awards season, the filmmaking equivalent of the World Cup and Olympics rolled into one. For three months a global series of events, centred around cinematic excellence, aims to highlight this year’s most daring, dramatic, and desirable films. Kicked off in November 2022 by the Frogs of Camerimage, the diaries of cinematographers are filled to the brim with ASC, BSC, Independent Spirit, BIFA, BAFTA, and Academy Award events. Championing the efforts of the global film community is serious business and there are some beautiful examples of the cinematographic craft to be praised in 2023.

Special mention must go to two outstanding Society members for their incredible pieces of filmmaking at Camerimage – Florian Hoffmeister BSC brought home the Golden Frog for best Theatrical Feature for his restrained and intimate photography of TÁR and Erik Wilson BSC was victorious in the Television Series Competition for his eclectic and idiosyncratic photographic approach to Landscapers.

Thoughts of accolades, awards and endowments led me to contemplate the creative origins of each of these projects. What was the launch pad for each of these filmmakers and how did they navigate the creative landscape?

From the first interview, through prep and all the way into post, every stage of the collaboration has challenges and choices to make. The creative collaboration of the filmmaking troupe is set within a never-ending succession of financial demands and deadlines. How do we ensure that these collaborations thrive under such adverse conditions?

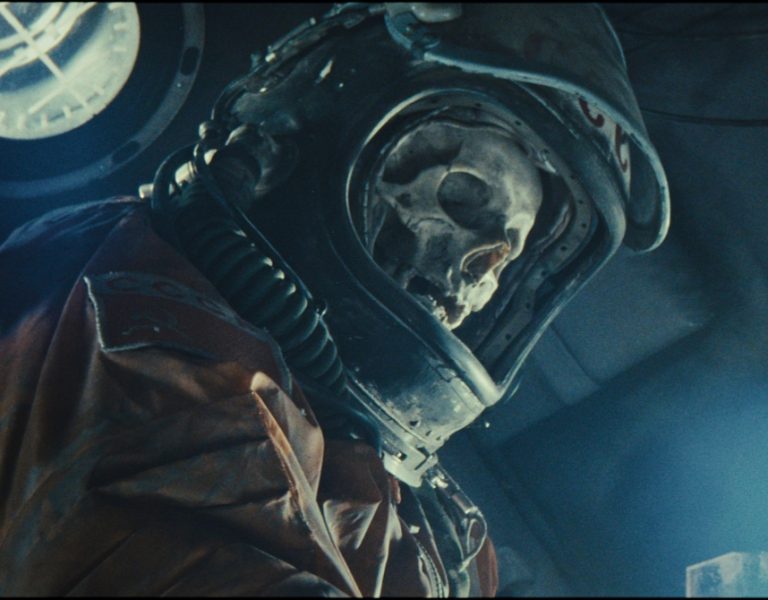

Like many creatives, I spend a few hours (days?) spiralling down the wormhole of new technology and some of the most interesting to surface this year are within the field of AI image generation, most notably Midjourney and Open AI’s Dall-E. I have been utilising both systems as a way of exploring new ways of thinking about projects over the last few months. The idea of partnering our own imaginations with an external source of inspiration is both beguiling and dangerous in equal measure, questioning the essence of creativity.

The creative process was broken down for the first time by psychologist J.P. Guilford and through the 1950s he worked to demystify the cognitive processes involved. He developed a theory of creativity and conjectured that the creative process requires at least three conditions:

- it must produce a novel idea or a response to one

- the resulting idea must solve a problem or accomplish some goal

- original insights must be sustained and developed to the full

As a response to his own work on the cognition of creativity he coined the term “Divergent Thinking” and proposed that it formed the main ingredient of the creative process:

- Fluency: the ability to produce a great number of ideas or solutions

- Flexibility: the ability to propose a variety of approaches to a problem

- Originality: the ability to produce new, original ideas

- Elaboration: the ability to systematise and organise the details of an idea

Can we determine whether our AI counterparts share these traits with us? Where does the artist’s personality sit within this model of cognition? Can we enforce our personalities into the AI process? Will the bots be trained to think on our behalf and really lighten the workload or are we destined for a conflict of interests?

A long time before AI was a reality the critic John Berger revolutionised the way that art was appreciated and introduced the idea of cultural aesthetics in his television series and book Ways of Seeing. He wrote, “Seeing comes before words. The child looks and recognises before it can speak. It is seeing which establishes our place in the surrounding world; we explain that world with words, but words can never undo the fact that we are surrounded by it. The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled.”

It may be that what we are seeing is the (re)discovery of a more childlike version of recognition, inspiration, and creation. As AI bots anchor themselves to simple words and concepts, use them to trigger responses and claw images from the ephemera, there is something both naïve and pure about this automated process. Perhaps cinematographers can learn a thing or two in the process, to channel primitive instincts and to respond with clear minds unencumbered by thoughts of success or failure.

Stay creative.