DISTORTED TRUTH

What we see may not be what is going on. Similarly, memories can distort and tell very different stories with the passage of time. These uncertainties form the basis of psychological thriller Chloe, which called for cinematographer Catherine Goldschmidt to create the look of these different realities, switching between them to eventually reveal the truth.

Chloe, created by main writer and director of three episodes Alice Seabright, starts as an examination of social media aspirations – central character Becky Green (Erin Doherty) alleviates the drabness of her life by obsessively scrolling through the Instagram account of the glamorous Chloe (Poppy Gilbert) – but soon becomes more sinister.

After Chloe’s unexpected death, Becky, takes on the persona of ‘Sasha’ to ingratiate herself with the dead woman’s friends. “The brief was clear that we would be with Becky entirely and the whole show would be shot through her point of view,” says cinematographer Catherine Goldschmidt, who had been discussing the possible look of the show with Seabright when plans changed due to the pandemic.

“There was a point where I was supposed to shoot the whole thing myself and then I contracted COVID when I should have been prepping with Amanda Boyle [director of the remaining three episodes]. I said she should have somebody to prep with, so Steven [Ferguson] came on board. But it was Alice’s wish that we all collaborate, so it feels like one cohesive story with a visual arc.”

In the end, Goldschmidt shot the first three episodes and Ferguson took over for the remaining three. “There are different visual threads going on,” Goldschmidt say. “The present day, flashbacks, and Becky’s anxiety flashes, where she’s imagining things. There are also fantasy sequences, which have a different tonality.”

Shooting was on a Sony Venice, with Panavision Primo Artistes as the main lenses. “I find the Venice incredibly versatile when it comes to creating different looks,” she says. “It has two native ISOs, and you can crop the sensors in a variety of ways, which I thought would be a great tool to capture the different looks.”

Becky’s home life in the rundown flat she shares with her mother is presented as slightly grubby, for which the Venice was cropped in Super 35mm mode rated at native ISO 2500 but pulled down to ISO 1250. “We wanted to fight against the typical tropes of making Becky’s world dull and grey. We felt it ought to be messier in terms of colour palette, with sodium vapour lights coming in from the street and the blue glow of the phone, for example. This is in contrast to Chloe’s world which is very presentational and controlled colour wise.”

This glossier lifestyle is first seen through the Instagram pictures Becky looks at on her phone. These start out as still images of Chloe, her rich, well connected husband Elliot (Billy Howle) and their entourage and then come alive. “We wanted to give the still to moving sequences an extra glossy sheen because it is the most aspirational imagery in the show,” says Goldschmidt. These sequences are high contrast, saturated in colour and because of the square format of social media, are framed quite centrally.

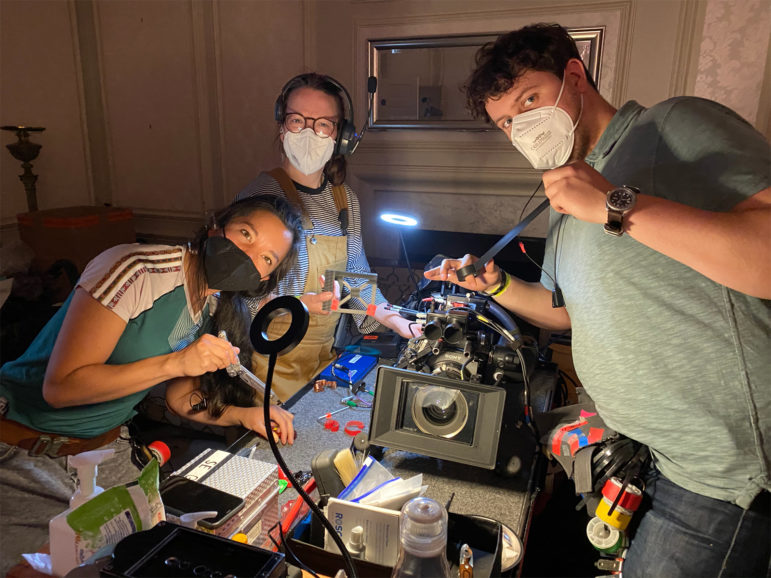

“When Becky becomes Sasha and enters Chloe’s world, we chose to shoot the entire 6K, large-format sensor to show the scope and potential of her new, exciting, and glamorous-seeming life. I rated the camera at the native 500 ISO for a very clean look. Whereas Becky’s past, shown in flashback, we shot on a Canon 8-64mm S16mm zoom, cropping the sensor size right down, highlighting the intimacy of her memories but also their somewhat narrow point of view. Here, I rated the sensor at 2500 ISO, and we also rebuilt it into Rialto mode, allowing us to move the camera more freely in this stripped-down form.”

Another look in the drama is what Goldschmidt describes as “the in-between place”, where Becky interacts with Josh (Brandon Micheal Hall), a marginal figure on the art scene that she meets while masquerading under yet another name. “Josh is the middle ground, where Becky is still sort of being Sasha but is also being more herself. To do this we used colourful lighting and some moving camera. When Becky’s at home, there’s a lot of handheld work, the movement is quite organic. When she’s Sasha, there is more Steadicam, dolly, and stick-mounted work. But with Josh, it can be anything. In his apartment we used neon and when they go to a bar there’s more colourful light sources. We wanted to have a little more fun with Josh because that’s what Becky is doing.”

Steven Ferguson adds that there is a sense of movement throughout the show, most of which is motivated by Becky. “We would often build the blocking around Steadicam developers – shots built by A camera operator John Hembrough – and every visual decision was guided by Becky’s subjective experience,” he says. “The only time we moved away from motivated movement was in the scenes in Elliot’s house, where we would employ creeping push-ins and slow zooms to suggest a sense of being watched, or a ‘presence’. This helps achieve the sense of a haunting that Amanda [Boyle] was after.”

The second half of Chloe feels more like a horror film or ghost story as Becky realises what happened to the title character and that the same could happen to her too. Rather than overt horror movies, the cinematographers used psychological stories of isolation, paranoia, and control as references. For Ferguson, it was Todd Haynes’ Safe (1995, DP Alex Nepomniaschy), Swallow (2019, DP Katelin Arizmendi), Martha Marcy May Marlene (2011, DP Jody Lee Lipes) and Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite (2019, DP Kyung-pyo Hong). The last film in particular informed the lighting choices from episode four onwards. “There was a move away from warm tungsten sources into more mixed hues plus green and sodium gels providing a dirtier look to the world of privilege Becky used to look at enviously,” explains Ferguson.

Goldschmidt’s main reference was Anthony Mingella’s The Talented Mr Ripley (1999, DP John Seale ASC). “In the second block the story becomes more of a thriller,” she says. “The work we had to do in the first block is more about the character and getting the audience connected to Becky and her very subjective experience. Alice and I watched a lot of films before shooting, but the touch point for us was The Talented Mr Ripley, which has a similar complicated and untrustworthy character – an outsider who you can relate to, despite all the despicable things they wind up doing.”

Like Ripley, Becky is not the most likeable of protagonists but, unlike Ripley, the viewer comes to understand her motivations and ultimately feel sympathy for her. A process that benefits enormously from the look of the different worlds she passes through on her way to a form of resolution.