LIFE THROUGH THE LENS

With an undeniable passion for filmmaking, Syrian refugee Ayman Alhussein was given the opportunity to explore and nurture his natural talent. During the inspiring transformation that followed he made the leap from being filmed by a documentary crew to stepping behind the camera to shoot a short film inspired by his experiences as an asylum seeker in the UK.

While many filmmakers liken the creative process to a journey, Ayman Alhussein’s unique personal voyage saw him go from being the subject of a documentary about his experience fleeing war-torn Syria to becoming a camera operator on a short film inspired by his time as a refugee in the UK.

“I feel empowered to tell stories now. When you bring people together who care about the story, like we did when making our short film, you can deliver something beautiful and create an impact,” says Alhussein about the transformative experience of shooting short film, Matar.

The journey began with a chance encounter in 2015 when Alhussein met cinematographer Jack Thompson-Roylance and his director brother Boris with whom he runs production company Deadbeat Films when they were shooting a documentary in Calais, France. “It was a very hostile environment in the UK. David Cameron was in power, and refugees were being dehumanised, and we travelled to the infamous Jungle camp to document the situation refugees faced,” says Thompson-Roylance.

With documentary having always defined the visual language of his filmmaking practice, the cinematographer set out to “tell human stories while making real personal encounters along the way”. When the filmmakers met Alhussein at the migrant camp, he became the centre of the documentary project and inspired its title – Ayman.

In 2015, escaping the war and the government, 18-year-old Alhussein fled from his country of Syria and first travelled to Turkey, where he studied dental prosthetics. However, as he could not live there due to not being able to have a work permit as a refugee, he made the journey to Europe while capturing footage on his phone. “When I met Jack in Calais and discovered they were making a documentary we collaborated and my filmmaking journey properly started,” he says.

Once in the UK, Alhussein claimed asylum and wasn’t granted the right to stay and work in the country until two and a half years later. “So, I was in limbo waiting to be interviewed and have my application processed. It was a very bad experience having to report to a police station every two weeks just because I was an asylum seeker. It could have been possible for me to experience modern slavery too in the UK as business owners would approach asylum seekers like me to exploit us for cheap labour,” he says.

“I had a dental prosthetics degree I couldn’t use because I wasn’t allowed to work, but I also had a passion for filmmaking. I didn’t see enough representation of the refugee community in the UK, and I thought maybe I could tell my own stories. So as an asylum seeker, I approached individuals and charities like Choose Love – one of the biggest charities supporting asylum seekers – which later became our impact partners and funded part of our short film Matar which was inspired by my experiences and followed on from the short documentary Ayman.”

Not allowed to embark on any paid work, Alhussein worked on projects for charities for free and completed work experience at production company Screencult and the BBC while receiving guidance from Thompson-Roylance amongst others to enhance his skills.

“In September 2019 I received papers granting me the right to work in the UK which I presented on stage at the Ayman premiere – it was a very special moment,” he says. “The film wasn’t released until then, due to fears of what the government might do.”

An inspiring experience

The next stage of Alhussein’s blossoming film career saw him work as an actor and authenticity consultant on The Swimmers (2022) – the inspiring true story of courageous Syrian refugee sisters, directed by Sally El Hosaini and lensed by Chris Ross BSC. “Working with and being encouraged by people like Sally and Chris inspired me. I thought I want to make something, I’m ready to tell stories from our perspective,” he says.

With a short film narrative in his mind, Alhussein approached Thompson-Roylance and Deadbeat Films and a team was formed including actor Ahmed Malek and Elmi Rashid (The Swimmers) and Alhussein’s friend and fellow Syrian refugee and associate producer on The Swimmers, Hassan Akkad, who joined as director.

“We tried to bring some of The Swimmers team together on Matar such as Deniz Ersoy who’s from Turkey and moved to the UK two years ago. She was A Cam 2nd AC on The Swimmers and took on the same role on Matar,” says Alhussein. “Deniz doesn’t know many people in the UK and was struggling to get jobs. When I brought her on board and introduced her to Jack, Boris, and Hassan, they said how amazing she was. There are a lot of excellent people from different backgrounds who are not being offered opportunities.”

WaterBear – a streaming platform dedicated to the future of the planet with a vast catalogue of free long and shortform documentaries and films – commissioned Matar. Thompson-Roylance feels the short film project stands out due to its docu-fiction approach combined with the lived experience of the crew: “The film champions asylum seekers like director Hassan and Ayman as a camera operator. It delves into documentary but is paired with the cinematic language I’ve been invested in as a cinematographer.”

A behind-the-scenes film (The First Drop of Rain; Making Matar, available via WaterBear) was captured by Deadbeat Impact – a newly developed department within Deadbeat Films – to share this unique approach to storytelling.

While highlighting docu-fiction as a fairly young and unexplored medium, Thompson-Roylance praises filmmakers who have excelled in the genre such as director Benh Zeitlin and cinematographer Ben Richardson ASC and their work on Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012) which was inspired by a true story. Other significant stylistic inspirations included the magical realism and intimate camerawork of Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Biutiful (2010), shot by Rodrigo Prieto ASC AMC; painter Edward Hopper’s isolated characters and use of framing; and photographer Saul Leiter’s use of texture.

“One of the biggest lensing references was James Laxton ASC’s work on Moonlight, including the slow-motion portraits of characters looking into the camera,” he says. “We also discovered he used the Hawk series to create a painterly look with the vintage glass which influenced our choice of lens. This technique was a great metaphor for the disconnection Matar feels from the real world.

“We also played with the docu-fiction approach of using A and B Cam during conversation scenes and a lot of guerrilla shooting was juxtaposed with clear cinematic language. The merging of the two styles providing fertile ground for the project.”

Building a look book before pre-production began permitted Alhussein and Thompson-Roylance to align the way they wanted to tell the story while providing the art department with a visual reference bible. As the project was greenlit quickly, director Akkad, Alhussein and co-writer Brook Driver developed the script whilst creating the shotlist. “It was beautiful to work with a camera operator that early in the shotlisting when the visual language was already aligned and we could have lengthy conversations about the references,” says Thompson-Roylance, who while enjoying operating, found the project liberating as it allowed him to spend more time on the monitor and consider the lighting in more detail.

“It was a very fluid conversation between me as cinematographer and Ayman as camera operator because we’ve been friends for years. It was also an opportunity for Ayman to grow as a cinematographer and I wanted to get him involved in the process as much as possible.”

Flipping the lens

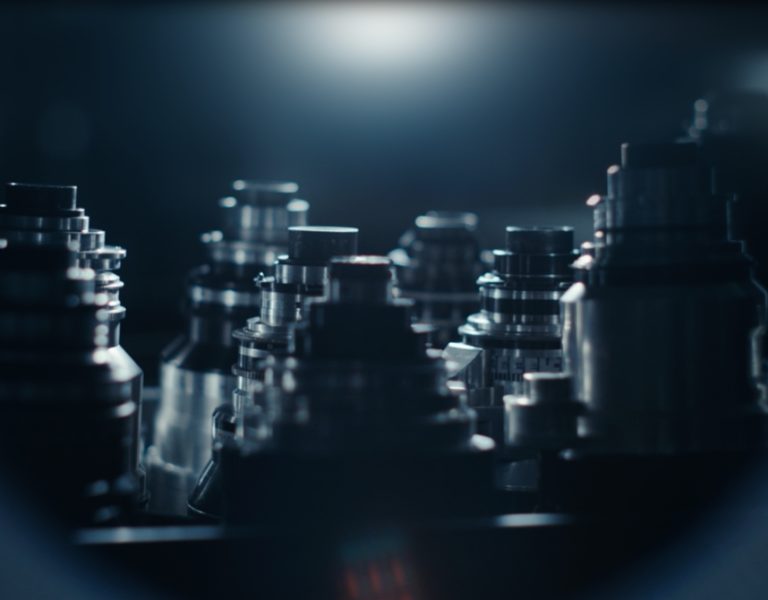

The authenticity at the project’s core was integral in the filmmakers’ decision to work with the Hawk V-Lite anamorphic lenses. “We wanted it to look beautiful, but also have the anamorphic distortion to make people really feel the story rather than creating a buttery smooth image,” explains Alhussein.

As building a diverse crew to create the film was paramount around 40% of the production team were from the migrant community, with a higher percentage on the camera crew. “It was important to work with people who are passionate about the cause and aware of the reality because we wanted to tell the story that is not being told authentically,” says Alhussein. “Rather than just doing the job and going home, our team felt like they were making a change.”

Headed by the team’s Head of Impact, Mabel Evans, and due to the sensitive nature of the subject matter and people with lived experience being on set, Deadbeat Impact employed a mental health officer who cast and crew could talk to if needed when triggering scenes were being captured.

While Alhussein did not need to speak to a mental health officer on set, knowing there was someone there if he needed to gave him confidence: “Making the film was a very special experience but also emotionally difficult at times, especially as I felt like I was shooting myself. Actor Ahmed Malek was amazing and at times for a split second I’d forget I was filming fiction and really be in the moment. That was empowering too as I felt like I was really telling stories of my own.”

Alhussein was exactly the type of camera operator Thompson-Roylance wants on set: “He was calm, considered, and collected, especially after everything he’s been through. It’s helpful for the actors to have that sort of energy on set. It was also a beautiful process because I met Ayman seven years ago, documenting him in a camp, and now the lens has flipped and he’s the one holding the camera, creating the imagery, and reflecting on his own story.

“It was wonderful to see him develop his skills as a camera operator during the shoot. One shot I’m so proud Ayman captured follows Matar through Soho and whips around a corner before falling into shadow. It’s a complicated shot which Ayman became symbiotic with Matar to capture.”

Deadbeat Impact employed a sustainability supervisor and abided by the BAFTA albert certification carbon tracking. “We were also conscious of the type of food we ate, recycling was on point, we used electric vehicles to travel and tried to minimise vehicle usage,” adds Thompson-Roylance. “And in terms of the camera department, it was crucial to keep wattage count down and be sustainable while also being resourceful.”

In line with minimising wattage, the production relied heavily on practical light and used predominantly LED fixtures, with the biggest lamp being an Aputure Light Storm 1200d which they used to punch through windows and motivate the sun. “We used many Aputure fixtures which also meant we were swift and ergonomic when working with LEDs as they could be thrown up quickly and we didn’t have to wait for them to cool down,” says Thompson-Roylance. “Even though we played with cinematic nuances in terms of grip and lighting, we wanted the lighting to delve into realism with a lot of practical lamps, many B7 Aputure bulbs, and Astera Ttitans rigged into existing fixtures.

Having developed a shorthand with Thompson-Roylance over the years, gaffer Alex Rice was aware of the way the cinematographer likes to light, working with a lot of negative fill. To keep the set-up portable, they relied heavily on natural light for exterior shots, sculpting it to create mood and tone.

Art imitates life

Following on from Alhussein’s experiences depicted in the documentary, docu-fiction production Matar is inspired by his encounters as a delivery driver in London during lockdown. “I met a lot of other people who were making a living from being bike couriers, like the character Matar in the film, so we combined my experience as an asylum seeker and those stories I heard when I came to the UK in the script.” Through Hiba Noors involvement in the behind-the-scenes film, they took the lived experience to another level, in that Hiba was living through the experiences of the protagonist Matar, and was invited by the impact team to live sketch the scenes unfolding in front of her.

Shooting took place in Walthamstow – where Alhussein lived when he was delivering food – and other delivery hotspots across London such as Dalston and Soho. These locations and the number of late-night scenes that would be captured there dictated the choice of camera, with the filmmakers selecting the Sony Venice – supplied with the lenses by ARRI Rental – as their A cam, mainly for its dual ISO capabilities and ability to achieve an impressive exposure when shooting at 2500 ISO.

When experimenting with camera bodies and lens sets during a test day at ARRI Rental, the Venice also stood out due to the Rialto mode which played a pivotal role in how Matar was shot, allowing Alhussein to be more liberated in his camera operation when working with the extension system to remove the front image block of the camera.

“Shoutout to Joe Harvey, our incredible rollerblade operator, who came to the prep day, rigged up on the Rialto with a Mōvi Pro camera movement system and was an absolute delight speeding along during the shoot, beautifully tracking Matar,” says Thompson-Roylance. “As most of the film takes place following Matar’s bicycle, we needed creative ways to capture this. The cinematography and camera operating always aimed to immerse the audience in the landscape of the main character. I also must commend 1st AC Juan Minolta who I’ve worked with for about six years. Even when we were shooting Matar wide open on a long lens whilst simultaneously tracking and dollying, he’d still keep it sharp.”

The team worked with a muted palette, with an emphasis on beiges and browns against the red delivery bag (inspired by The Red Balloon) signifying Matar’s determination. Using the look book as a reference, the filmmakers built a custom LUT with colourist Jonny Tully at Cheat which was carried all the way through production. “The LUT highlighted reds but also brought in the blues as we shot in winter and wanted to embrace the coldness while still having these little pockets of warmth in the practicals, with orange and red hues symbolising hope for the future,” says the cinematographer. “It was so great to have those conversations with the colourist earlier so everybody could get on board with the visual language.

“The only thing we didn’t have during the shoot was grain, but Cheat use a process where the grain is authentically built in.”

The addition of film grain to digital material is the final seasoning of the overall look and feel to many grades at Cheat. “Just as a beautiful dish can be ruined by cheap sodium chloride salt, a great grade can be ruined by bad grain,” says Toby Tomkins, senior colourist and founder of the post house. “Grain shouldn’t simply be slapped on over the top, so colourists at Cheat ensure that the grain is well embedded with the digital material, so that it doesn’t feel like an overlay.

“As well as the matching of the source material to the desired grain level, our colourists also dial in different amounts of grain to different tonal ranges (shadows/midtones/highlights) and can vary the amount across colour channels to better emulate real film, and if departing from our emulation, find a texture that is perfect for the project.”

To show the emotion, narrative journey, and catharsis of Matar while highlighting the feeling of alienation and insecurity some sequences used mixed media in the form of surveillance cameras and daunting top shots captured by GoPros with intercom effects created using VFX. Bodycam footage captured using a Sony FX6 was an effective tool to convey disorientation, especially in the first montage when Matar is making deliveries by bike.

“The bike plays a key role in the story. The film is about opening a window for people to understand and get an insight into the lives of these shadow communities. Matar is a cool guy trying to survive and the film is also about his love affair with his bicycle that is allowing him to make a living, conveyed through macro shots of him lovingly assembling it in the garage,” says Thompson-Roylance.

“Those close-up shots of the detail of the bike, his hands and his emotions, make you connect with the person as the closer you are to them, the closer you are to the story,” adds Alhussein. To achieve this the filmmakers often used diopters due to the limited close focus of the vintage lenses. The Hawks were also combined with Tiffen Black Satin filters to enhance the look.

The final scene was powerful for the filmmakers to shoot. It sees Matar, having fled from police, get hit by a police van and then thrown into the back of the vehicle. “In terms of our visual approach, it suddenly becomes disorientating, and the handheld camera work is very shallow, followed by a juxtaposed God view top shot,” says Thompson-Roylance.

“The final shot is one of my favourites and references Saul Leiter’s framing within the frame. It’s an uninterrupted oner of Matar in the back of the van as the call-to-action text appears to the side of him. We lit it with a DMG Dash inside the van to create a very high contrast ratio and his breath against the window is devastating because he becomes nothing more than an animal who should be locked up to the police. It’s almost like he’s been dehumanised.”

The synergy between the two projects – documentary Ayman shot on a Sony Alpha A7S II and DJI Ronin system as an almost meditative cinematic journey and short film Matar captured on the Venice – is clear in such scenes. “In the documentary you discover that to reach the UK I travelled between Paris and London in a suitcase. It was so hot and sweaty I couldn’t breathe. That is connected to the scene in the back of the van and Matar’s breath on the window,” says Alhussein.

In March this year, when the premiere screening of Matar took place at the Soho Curzon in London, all three films – the documentary, short and behind-the-scenes – were shown back-to-back. “To see this journey and progression in terms of storytelling and cinematography was powerful,” says Thompson-Roylance. “Ayman is like a microcosm for the refugee experience, and that journey, and development has been really emotional.”

Continuing that journey, and following feedback received from those who have seen the short, the team are now planning to develop the script into a feature film. “After the premiere, people reached out and said how powerful it was, especially those from the migrant community, my refugee friends and Hassan’s refugee friends. They said they felt represented in this film and found it very authentic,” says Alhussein.

Having spoken to DPs who have experimented with shorter shooting days on features, Thompson-Roylance would like to follow suit when shooting the feature-length version of Matar to benefit from additional time to review footage and have discussions mid-shoot.

Creating change

The impact campaign which has been prominent from the beginning of the project will continue to be integral when developing Matar as a feature film which will then be used as a catalyst for social change. “The timing of the film couldn’t be more important. Five days before the premiere, UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak announced the Illegal Immigration Bill banning refugees, and we had an emergency meeting to change the call to action in the film to highlight exactly what’s going on at the moment.”

As well as encouraging people to sign Choose Love’s petition through the production (which received 2,500 signatures just from people attending the premiere), the filmmakers organised pop-up events in Soho with Choose Love and WaterBear inviting people from the migrant community to screenings of the film followed by a Q&A with some of those who created it. Deadbeat Impact are keen to continue the legacy of the campaign and approach to storytelling through initiatives throughout Refugee Week (19-25 June) in partnership with Counterpoints Arts and the film’s existing partners.

“If we can take anything away from this project, it’s the empowerment it can give young asylum seekers because it’s a real journey for refugees living in the UK and it was a pretty depressing time for Ayman initially, feeling a lack of support,” says Thompson-Roylance.

Alhussein believes he is “one of the lucky ones” to have met Deadbeat Films and the production company that offered him work experience while he was an asylum seeker. “I must also thank Chris Ross. When we met on The Swimmers, I told him I wanted to make films but didn’t know how to get into the industry as it’s hard being trusted as a refugee. You come to this country with nothing, you’re fleeing war, and you have to start a life from scratch.

“Chris then offered me a job on his recent film, The Greatest Escaper, as a trainee where over a few months I learned the etiquette of film sets in the UK and it marked a big shift for me from being a one-man band shooting charity videos and corporate films to collaborating with Jack on short film Matar where we had more resources.”

Alhussein values the help of individuals such as Ross, Thompson-Roylance and other fellow filmmakers including camera operators Ilana Garrard ACO Assoc. BSC and Steadicam operator, DP Jamie Cairney, Hannah Jell (who was also camera operator for some scenes in Matar) who provided support and advice along the way which has helped him get to the position where he could shoot Matar.

“There are a lot of people who want to tell their stories. Some might argue people should be hired if they have enough skill to do the job, not based on their race or where they come from. But we’ve proven when working on The Swimmers – with Hassan and I acting as consultants – that people with lived experience can help make a great film. They just need to be given the trust and opportunity to prove themselves.”

Recognising how difficult it can be for asylum seekers in the UK and inspired by Matar, Deadbeat Films are planning to build mentorship programmes into their future shoots, funded through corporate sponsorship. “We want to build a programme to be able to work with young people like Ayman, who wouldn’t usually be given the opportunity and platform to develop their skills, and hopefully help create the next generation of diverse filmmakers,” says Thompson-Roylance.

Alhussein continues: “We will be looking at placements on film sets initially. But it won’t just be for filmmaking; the impact plan of Matar is to develop a model where if someone from a migrant background is interested in engineering, web design or anything else, we will try to connect them with companies or agencies who could offer work experience. That’s what I did when I was an asylum seeker. It’s not paid but when you’re just sitting around doing nothing, it’s not good for your mental health, so this sets them up so they’re ready to go, they have a skill and can have a career.

“As everybody has really connected with Matar, especially those from migrant backgrounds, we would like to work with people from diverse backgrounds once again to create the feature length version and continue the story.”