Shadows make good movies

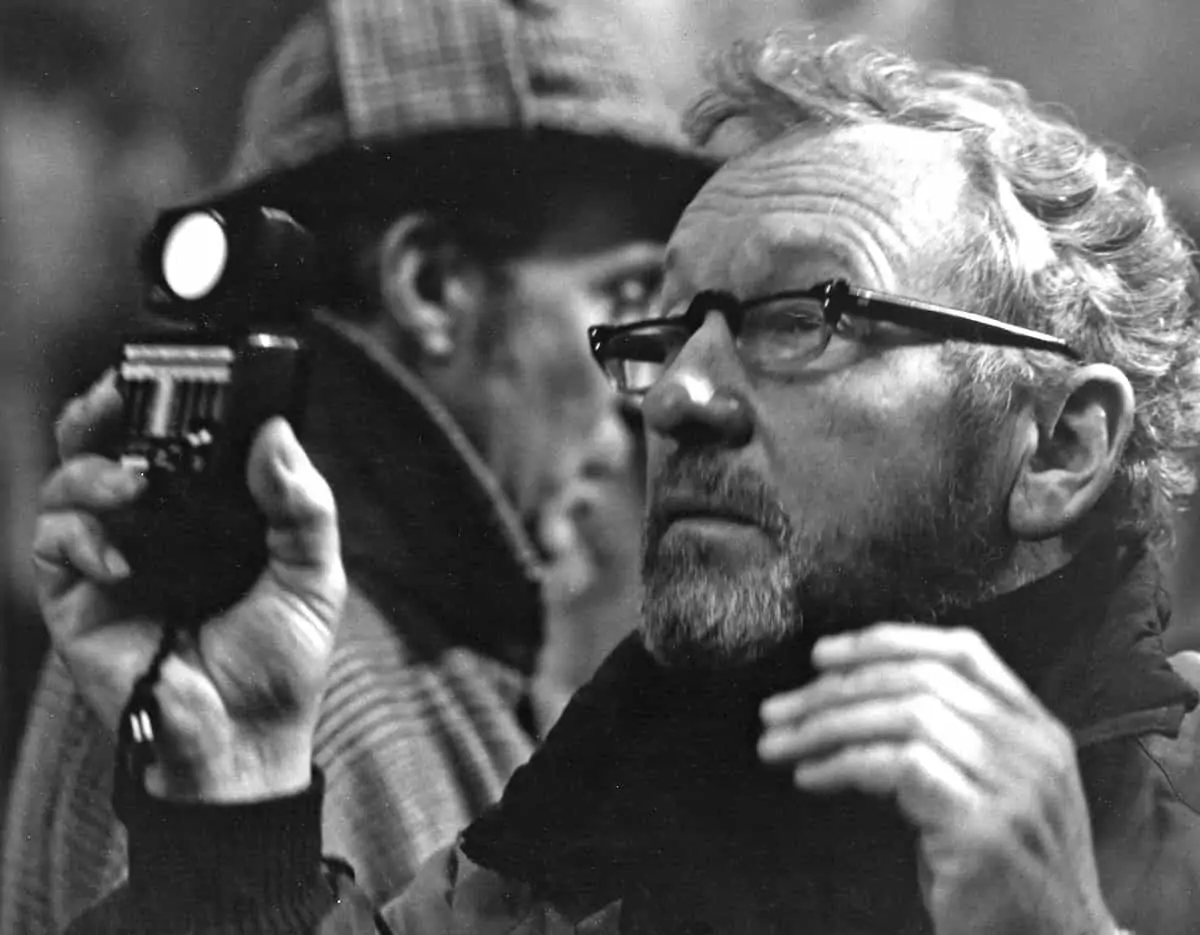

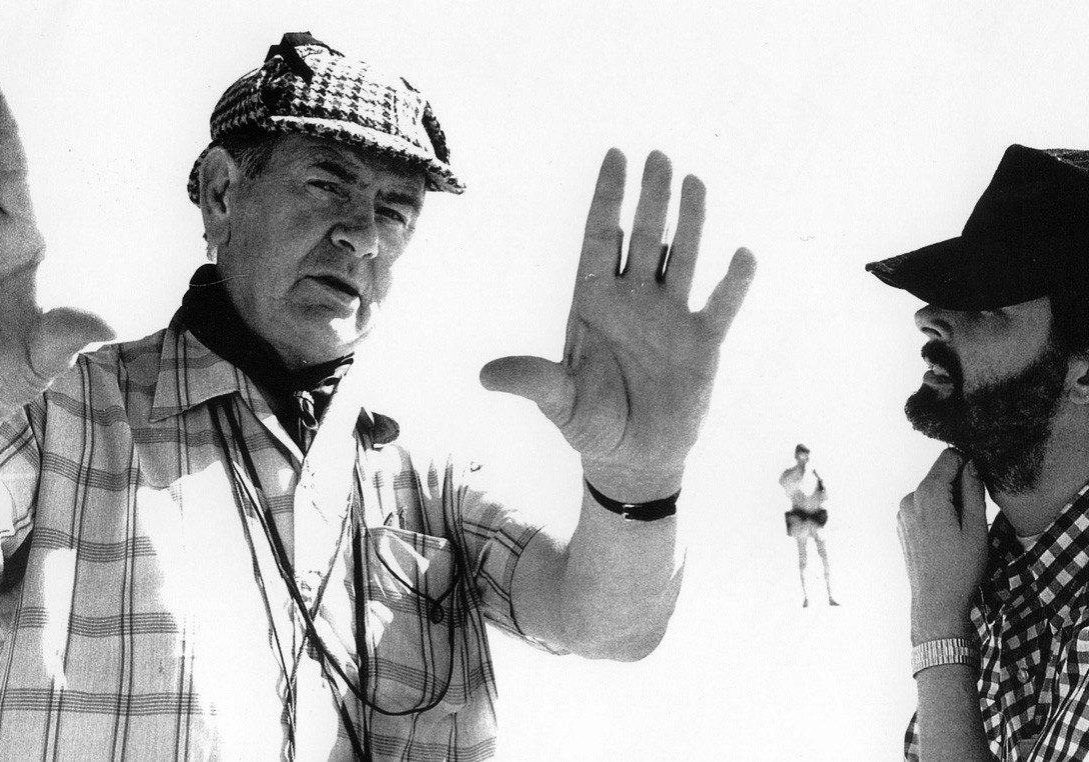

Clapperboard / Gilbert Taylor BSC

Shadows make good movies

Clapperboard / Gilbert Taylor BSC

BY: Kevin Hilton

Most people have some kind of plan in mind for how they would like their lives to unfold, but few of us set definite goals, and even fewer manage to achieve them. Gilbert Taylor, honorary member of the BSC and an acknowledged master of black and white photography, decided when he would begin lighting films and, away from the set, resolved to become a dairy farmer and ended up keeping 250 cows, writes Kevin Hilton.

Now aged 97, Gil Taylor can look back on a career that began in the early 1930s, during which he lit 65 feature films, numerous television episodes and countless commercials. The son of a successful Hertfordshire builder, Taylor started learning his future craft at the age of ten while visiting his father’s brother, a newsreel cameraman. These visits gave Taylor valuable experience in operating and stripping down his uncle’s hand-cranked Williamson camera and developing negatives. “By the time I became a camera assistant, when I was 15, I already knew a great deal about the business,” he says.

Taylor started out in films at the studios of Gainsborough Pictures as an assistant on creaky farces and a romance before his first experience of working with a director who left an indelible impression not only on cinema but on Taylor himself. Alfred Hitchcock was an in-house director during that time and in 1932 directed a chase movie called Number Seventeen. Taylor calls it an "amazing film" because of the "brilliant camera work" by Jack E. Cox and Bryan Langley and the special effects, many of which Taylor did himself, creating early mattes to fill in the roofs of dilapidated buildings. He applied similar expertise in 1955 for The Dam Busters.

Taylor did not work with Hitchcock again until the director returned to London to make Frenzy, but they had stayed in touch and developed a mutual admiration for each other. “Hitch loved me and I loved him,” Taylor says. “He was a gentleman and didn’t want to have anything to do with the camera, leaving anything to do with it to me.” This was partly because Hitchcock prepared every shot on storyboards, but Taylor says in his early days the director was told by cameramen not to look through the lens.

Gil Taylor continued to be busy for the rest of the 1930s, including ten Paramount quickies as operator to “very good” cameraman Ernie Palmer. When the war came Taylor volunteered for the Air Force and had “six years of wartime filming”. By 1942 Churchill was looking for cameramen to fly in Lancaster bombers to document raids on Germany and Taylor joined a small group of operators, which eventually became the RAF Film Unit.

End of the World Pictures

After the war Taylor worked for Two Cities Films, and set himself the target of lighting his first film by 1948. He achieved by becoming director of photography on The Guinea Pig, the first of several social satires by John and Roy Boulting. Taylor’s next film, also for the Boultings, was Seven Days to Noon, which, with Dr Strangelove and The Bedford Incident, is part of a loose trilogy of what he calls “end of the world films”. In it London had to appear deserted but, as Taylor says, the place is never completely empty, so he had to be up at five every morning to start shooting and took pills to keep himself awake for the seven week shoot - and then couldn’t get to sleep for some time afterwards. Part of the film’s unsettling atmosphere is due to Taylor B&W photography, achieved, he says, “with no lights at all”.

Dr Strangelove is noted for its glittering monochrome photography, with deep, heavy shadows, but the handheld camera work also adds to the jarring feeling. Taylor drew on work he had done for both John Boulting’s Journey Together and The Dam Busters, saying that, “The key is not to hold the camera completely still but to let it ‘breathe’ with you, to move with it.”

There was plenty of opportunity to try out this technique on A Hard Day’s Night, during which Taylor and his five operators had to cope with Beatlemania at its height. “We were up against crowds of screaming people,” he recalls. “There was no proper script at that stage and we were following the boys using 10:1 zooms on handheld Arriflexs. We did a lot of close iris stop stuff on that and it tuned out to be brilliant.”

British films of the early to mid 1960s continued to exploit the power of black and white film and much of Taylor’s cinematography was based on his work with the latent image, which involved developing the negative soon after shooting. He says he was also the first to employ bounce lights to put shadow around the set: “The aim was to get a stronger negative and good shadows in the final print. The shadows are what make good movies.

That is certainly true for Taylor’s first two outings with Roman Polanski, Repulsion and Cul-de-Sac. He describes the former as “an exceptional film”, shot at Twickenham - “a marvellous studio that was run like a family business” - with the director acting out much of the action for his performers as his English was a little imperfect at the time.

Taylor ranks Polanski among the great directors, both in general and of those he has worked with, alongside Hitchcock, J Lee Thompson (Ice Cold in Alex, Yield to the Night) and Stanley Kubrick. The director of Dr Strangelove and 2001: A Space Odyssesy, to which Taylor contributed “additional photography”, apparently was not someone who looked over the DP’s shoulder, leaving him to get on with things. Polanski, on the other hand, “worked closely with us and was involved in everything”.

A director for whom Taylor does not have a good word is George Lucas. Star Wars is clearly still an experience that stirs up bad memories, including waiting for Lucas to make decisions: “I decided I wouldn’t do another film with him for anything.” Despite this Taylor spoke up for Lucas when nervous 20th Century Fox executives came to see what was going on, reasoning that the director had already shot so much material something could be put together later, rather than starting again with someone else.

Farms and films

To give some relief from the vagaries of the film business Taylor moved into farming in the late 1960s, keeping a heard of 250 Jersey cows on 150 acres. As strange as it might seem Taylor sees farming and filmmaking as having a lot in common as “there’s always something that can go wrong” but experience and ingenuity often triumph over adversity.

Taylor commuted from his farm to the studio and locations for The Omen, a colour film that has a black and white sensibility to accentuate the growing horror of the story. Taylor says getting the look took a long time and several tests, during which Taylor asked his wife Diane, who worked on many of his film in continuity and other capacities, to get some gauzes. All she could find were six pairs of 10-denier stockings, which Taylor put over the lenses. “When Dick Donner [director] saw the results he said ‘You’ve got it’,” Taylor recalls. “I enjoyed every bit of that film and got on very well with Greg Peck, who was actually afraid Billie Whitelaw was going to stab him in one scene because she was so convincing.”

Less happy was his time on Flash Gordon, which Taylor feels should have stuck to the style of the old Buster Crabbe serials. For the film Taylor constructed a frame comprising 24 1kW lights, known as the DINO lamp after producer Dino de Laurentis. “It produced a lot of light and we paid for it to be made ourselves,” he says.

"[on The Omen] I enjoyed every bit of that film and got on very well with Greg Peck, who was actually afraid Billie Whitelaw was going to stab him in one scene because she was so convincing."

- Gilbert Taylor BSC

Taylor also developed space lights but concentrated on cinematography instead of design, moving into the lucrative commercials market during the 1980s. He made only one foray into directing, helming an episode of the 1960s trendy crime series Department S. Not that he didn’t have offers: “Hitchcock wanted me to co-direct Torn Curtain and I made a mistake in not doing that, although I did fly to the States and they wouldn’t let me in.”

That kind of treatment naturally rankles but Taylor feels the US film industry finally accepted him when the ASC gave him its International Award in 2006. He does not have a display case full of trophies, but won the BSC best cinematography award for The Omen and the Society presented him with a lifetime achievement award in 2001. Unfortunately BAFTA nominations for best British black and white cinematography on both Repulsion and Cul-de-Sac went unrealised.

The film establishment might have taken time to appreciate Gil Taylor’s work, but those who make films and those who watch them have long recognised what he brought to the craft of cinematography, particularly in his black and white films, many of which are now being restored. Above everything Taylor says his main intention was to be “a good cameraman” and he can feel confident he achieved that aim.