Artistic Eye

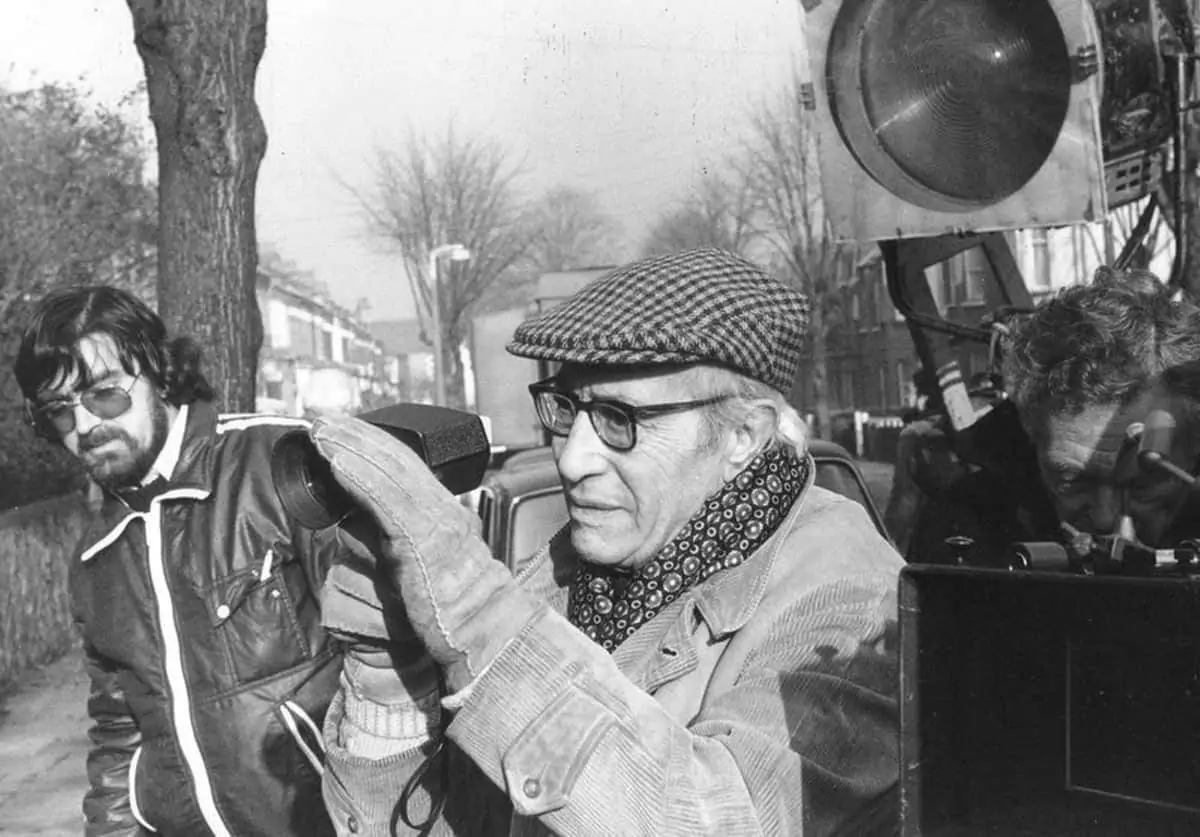

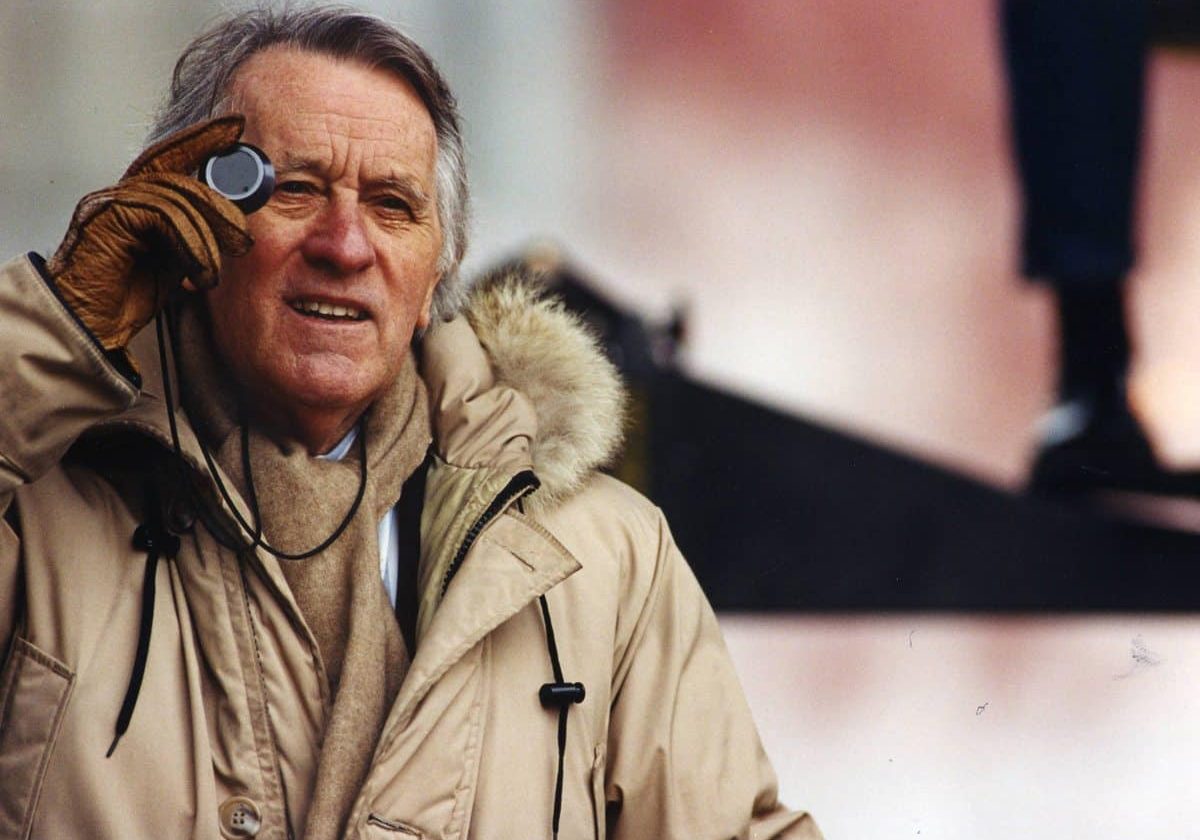

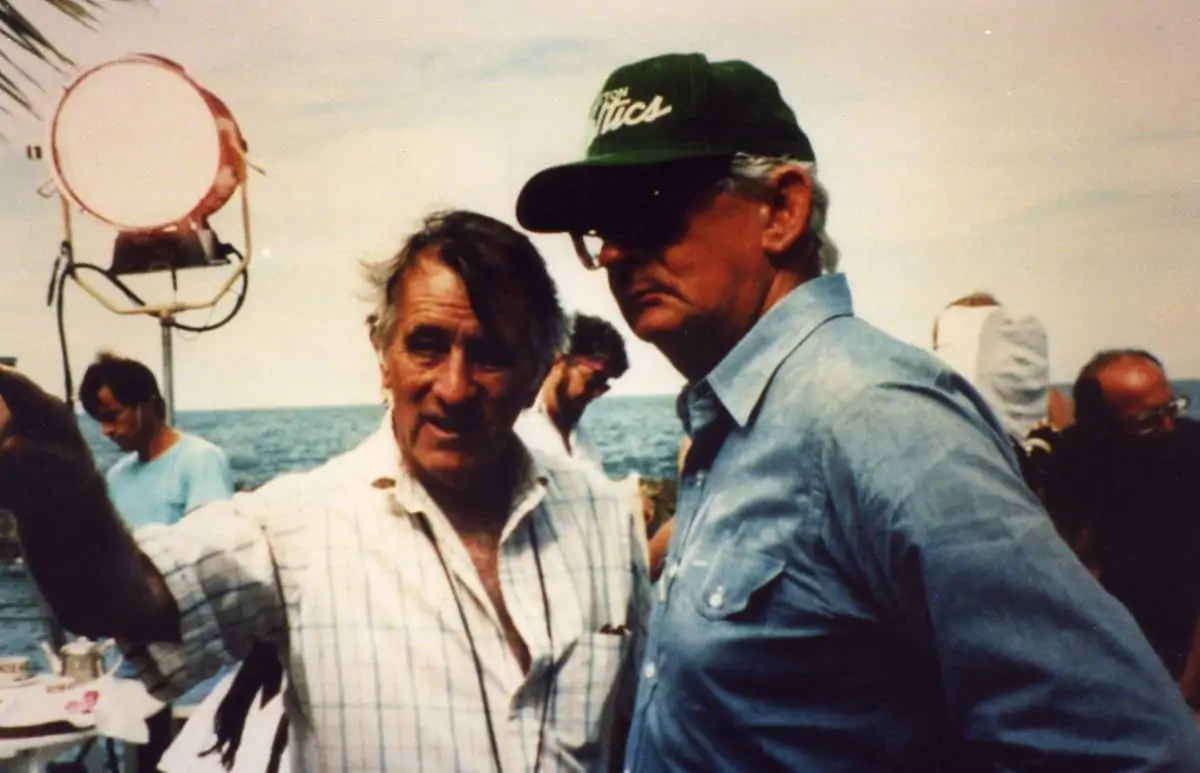

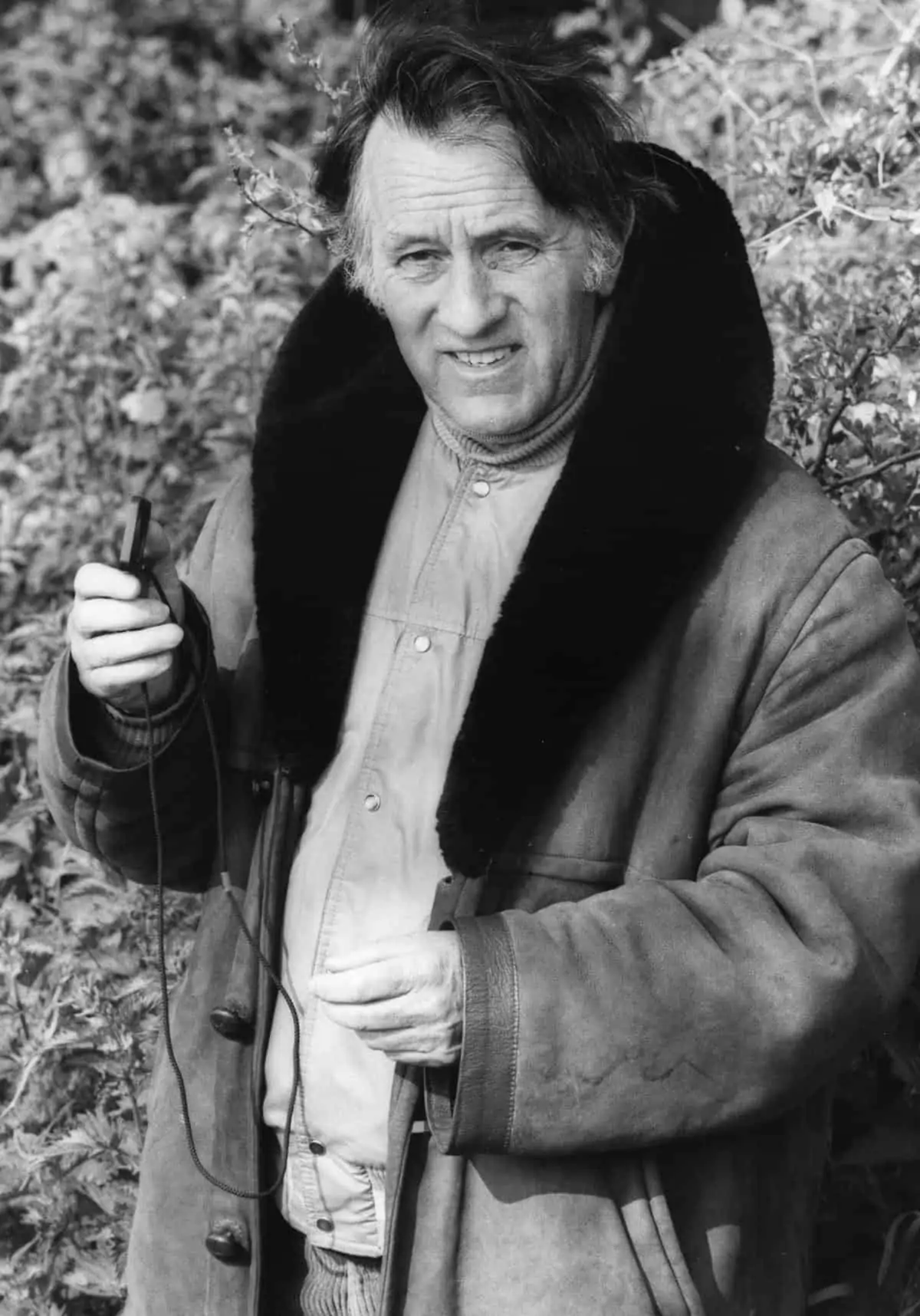

Clapperboard / Freddie Francis

Artistic Eye

Clapperboard / Freddie Francis

The late Frederick (Freddie) William Francis was born in Islington, North London in March 1917. After leaving school he went to a technical college to study engineering. Whilst there he wrote an essay on film and was given the chance to visit the Gaumont British studios in Shepherd’s Bush, West London. This inspired him to try and get into to the film business, in which he went on to win two Academy Awards for cinematography, and a cult status as a director.

He saw an advertisement placed by stills photographer Louis Prothero. He got the job, remaining with Prothero for around six months, during which time he did some work at Ealing studios on Stanley Lupino pictures.

Francis went on to get a job at British International Pictures (BIP) Elstree as a clapper loader. His first film as a clapper boy was The Marriage of Corbal (1936), photographed by Otto Kantureck.

Later in 1936 he met Oswald Morris, who became a great friend. Morris said: “ I was working at Pinewood studios on a quota quikie, and in those days a cameraman would ask for a ten foot test at the end of a 1,000ft reel. This was torn off before the film was sent to the laboratory and processed at the studio. Freddie was there doing these tests, and I can remember him coming on to the floor with a print to show the cinematographer. That is where I first met him.”

During WW2 Francis was in the Army Kinema Service (AKS) shooting training films. He was first based at Aldershot and then at Wembley studios. Francis said: “ I went into the AKS and that is when I really started. I started operating and became a DP, which was great. It took a war to do it, but one got a lot of training.”

After the war he became a camera operator. His first film was The Macomber Affair (1947). For this he went to Africa with Oswald Borradaile and John Wilcox. Later he teamed up with Oswald Morris. Morris took him on as his operator on his first film as DP, Golden Salamander (1950).

Describing Francis, Morris said: “He was a wonderful operator, very experienced. On Moulin Rouge (1952) we were expected to do all sorts of strange things with the camera. Freddie was throwing the very heavy three-strip Technicolor camera around very well and it was a great help to me because I was occupied lighting it. Our characters worked wonderfully well. Our interests were the same, we loved ribbing each other and there was great banter between us. Freddie was great.”

Morris and Francis worked together on several pictures, the collaboration ending with Moby Dick (1956). Francis was DP on the second unit. Francis’s first offering as a main unit DP was A Hill In Korea (1956), shot in Portugal. A young Michael Caine was technical advisor. Other notable films include Room AtTthe Top (1959) and The Innocents (1960), both directed by Jack Clayton, who became a good friend of his. The Innocents was one of Francis’s favourite films. It was shot in B&W and in cinemascope. Clayton didn’t want it in scope but had to relent. Francis created an effect that at times gave a non-scope look that worked very well. He said it was the best film he had ever photographed. Asked if he usually worked with the same crew, he said: “I got the same crew if I could. I made the point of trying to get the same operator and chief electrician, which was the most important thing. If you could get those two you were home and dry.”

In 1961 he made his debut as a director on Two And Two Make Six. He went on to direct a number of horror films for Hammer at Bray studios and Amicus at Shepperton. He also directed two for the short-lived company Tyburn. These were The Ghoul (1975) and Legend Of The Werewolf (1975). His first was Paranoiac for Hammer (1963). Asked about the Hammer films, he said: “They usually took around six weeks to shoot, working from eight until six, five days a week. There was very little overtime. Hammer didn’t want to spend any extra money if they could avoid it. It was only on the rare occasion we went past six.”

In a filmed interview Francis said, “ The Hammer organisation, for a certain period was a great success, but it was set up on business lines rather than artistic lines. If any of us could get any artistic points in we would, but the overall operation was a business, financial situation.”

His widow Pamela Francis was asked if he loved directing as much as cinematography. “I think he loved directing, I think it wasn’t as successful as cinematography, but it was a question of breaks. Normally he had very good reviews for the pictures that he directed, but he was pigeonholed in the horror genre.”

"Our characters worked wonderfully well. Our interests were the same, we loved ribbing each other and there was great banter between us."

- Oswald Morris

Francis never regarded himself as technical. Pam Francis and Gordon Hayman said he had a good eye for cinematography and directing. Francis said: “I read the script and see how it should be shot in my mind. I then go on to reproduce it on the screen.”

Francis returned to cinematography. His comeback film was The Elephant Man (1980), directed by David Lynch. One of Francis’s favourite operators’ was Gordon Hayman. Hayman said: “I had just finished a film with Mike Hodges directing and Karel Reisze had been in touch with Hodges looking for operators. I had an interview with Reisze for the film The French Lieutenant’s Woman (1981). A couple of days later I got a call from Freddie, who was to be the DP. He said, ‘We have never met, I don’t know you – we have some extra shooting to do on The Elephant Man, which will take three days, are you interested?’ I accepted and that was the start of a long collaboration.

“Freddie had a great sense of humour, he said, ‘I’d like you to do these three days because we may hate the sight of each other.’ I enjoyed working with him very much.”

Francis returned to directing for The Doctor AndTthe Devils (1985), The Dark Tower (1987) and Tales From The Crypt (1996). On The Dark Tower he was credited as Ken Barnett. Pam Francis said: “Freddie took his name off the film because he was let down by bad special effects and other things. The name Ken Barnett was put on the film by the producer.” He returned permanently to cinematography following Tales From The Crypt.

Francis won a number of awards, including Oscars for Sons And Lovers (1960) and Glory (1990). Hayman operated on Glory but wasn’t credited due to a mistake. In his Oscar speech Francis praised Hayman, calling him, “My wonderful operator Gordon Hayman.”

Francis did quite a bit of television work including The Saint and Man In A Suitcase. When asked about working in TV he replied, “It’s no good asking me about my TV career because I have forgotten what I did in TV. I’ve probably forgotten not because I’m getting to the age where I forget everything, but I wasn’t very interested in them anyway, I found it very dull.” However, Pam Francis said he enjoyed working on the Black Beauty series.

Francis loved making films and shot his last film The Straight Story in 1989 at the age of eighty-two. He was asked by his biographer Tony Dalton, “What is the best advice you could give a cinematographer today?” Francis replied, “Don’t do it unless you love it, otherwise it’s a terrible job.”

Francis died on 17 March 2007. There is a bench that is dedicated to him in the Rhododendron walk at Pinewood studios.