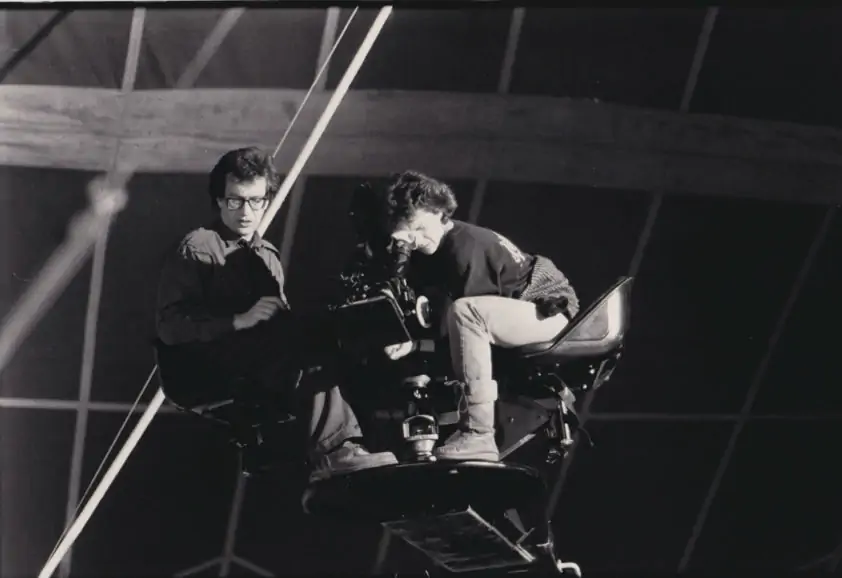

FAITH IN CINEMATOGRAPHY

For Agnès Godard cinema is “life energy, amplified.” One of the most remarkable and talented directors of photography, Godard has charted a consistent body of work for directors including Agnès Varda, André Téchiné, Claude Berri, Carol Morley, and most notably Claire Denis with whom she has shot 15 features. The recipient of the Pierre Angénieux Tribute at this year’s Cannes Film Festival shared highlights from her remarkable career.

Born in 1951, Agnès Godard traces her interest in imagery to her father. An amateur photographer, he took thousands of pictures of “the family, the house, landscapes, the car – everything” and would organise home screenings.

When he died, she assembled 4,000-5,000 pictures. “I realised he was very shy and didn’t talk much but that these images were like a gigantic memory and a kind of conversation,” she says. “They were also all taken under a certain contract – that of love.”

Growing up in the countryside she also learned about nature – “trees, mushrooms, butterflies.” As a teenager, “I would contemplate the light and I would be filled with a certain sensation, asking myself what I could do with that?”

She saw one or two films and was drawn to those that remained a mystery (by Jean Cocteau perhaps).

In part to sate her parents’ desire for her to follow a profession, Godard enrolled in a journalism course after school but the motivation to work with images rather than words compelled a change of career and she switched to Paris film school La Fémis.

“I’ve always been fascinated by the idea that when you see an image of another person looking through the lens there is this never-ending conversation you can have with them,” she says. “It will always remain a mystery, but this is an essential element to cinema. Faces are really the richest landscape.”

Godard was shy, like her father, but cinema was a way of daring to look at someone, she says. “I felt more comfortable trying to capture that look [on camera] than going and speaking to people.”

This is not voyeuristic, although cinema is perfect for that. “I don’t want to be intrusive,” she explains. “It’s more that we can never really know another person or what goes on in their mind but sometimes we watch an expression that says something unique about them.

“That’s why images are powerful. Images can make you feel like you could touch a person but as long you don’t – or can’t – then the mystery will go on and the desire won’t be destroyed. The beauty of cinema is that this feeling can last forever.”

Graduating in 1980, Godard assisted for some of the greats including Robby Müller NSC, BVK on Paris, Texas and Henri Alekan AFC on Wings of Desire. Of Müller, she says, “he was extremely technical and also a kind of a poet. His imagery just left me speechless.”

One encounter was so overwhelming she almost quit cinematography all together. As camera operator, she observed Darius Khondji AFC ASC lighting a scene in Prague in 1992 and realised that he was doing so with such conviction “because of his knowledge and because it suited his personality. He had found a way to light and shoot that suited him.”

She drew inspiration from this, finding the courage to continue to find her own way of working. She calls this ‘faith in cinematography’.

“It’s something I’m sure that all the great cinematographers like Philippe Rousselot, Bruno Delbonnel, Roger Deakins share. Everyone has a specific way to exercise their faith and that means cinematography offers such a wide variety of styles.”

Her own style developed after meeting Rousselot’s gaffer Jean-Pierre Baronsky and on films for Claire Denis (who Godard met on Paris, Texas) including I Can’t Sleep, Beau Travail, Trouble Every Day and Bastards.

“For me, you have to find the music of a scene,” she says. “I think I discovered that by working with the camera on my shoulder. You don’t frame the same way when the camera is on a machine or dolly. On your shoulder you don’t have much time. Your attraction to the subject is intuitive.”

For the same reason, Godard says she prefers the implicit truth of the first take. “At the beginning of my career I was the opposite. I would have to make sure everything was going to work, to rehearse, to be precise. Then I discovered there was something different in the first take because it was the first look. I opened up to the spontaneity of moving or framing to capture something unique and fragile that will be unlike anything before or afterwards.

“It’s also maybe a way to avoid what I would call illustration of the script. I believe that the fluidity of being present in the action produces a profound effect that you can feel.”

While constantly noting small details or wide vistas she might see daily, she is prepared to respond to what she finds on the day of filming.

“If we’re preparing to shoot interiors of a house on location, I’d set the lights, but I will change my mind if the natural light offers me something I find more beautiful. This idea drove me to change the temperature of light in the same movie. For instance, if I agree with the director and art director that we would be mainly in a warm colour temp I would try to keep a moment where we would change that. I’m afraid that by keeping the visual aesthetic the same during a film the audience will get used to it, so I like to change – just as it is in life sometimes.”

Her most recent work, shot in 2020, is La Ligne for director Ursula Meier. Godard says she is never happier than when collaborating. “Making a movie is a succession of collaborators including with my own wonderful crew – gaffer, key grip, camera assistant. Everyone is concentrated toward the same goal and that gives you energy.”

At Cannes 2021, Agnès Godard received the Pierre Angénieux Tribute, given for a director of photography’s impact on the history of world cinema.