Flower Power

Eigil Bryld / Tulip Fever

Flower Power

Eigil Bryld / Tulip Fever

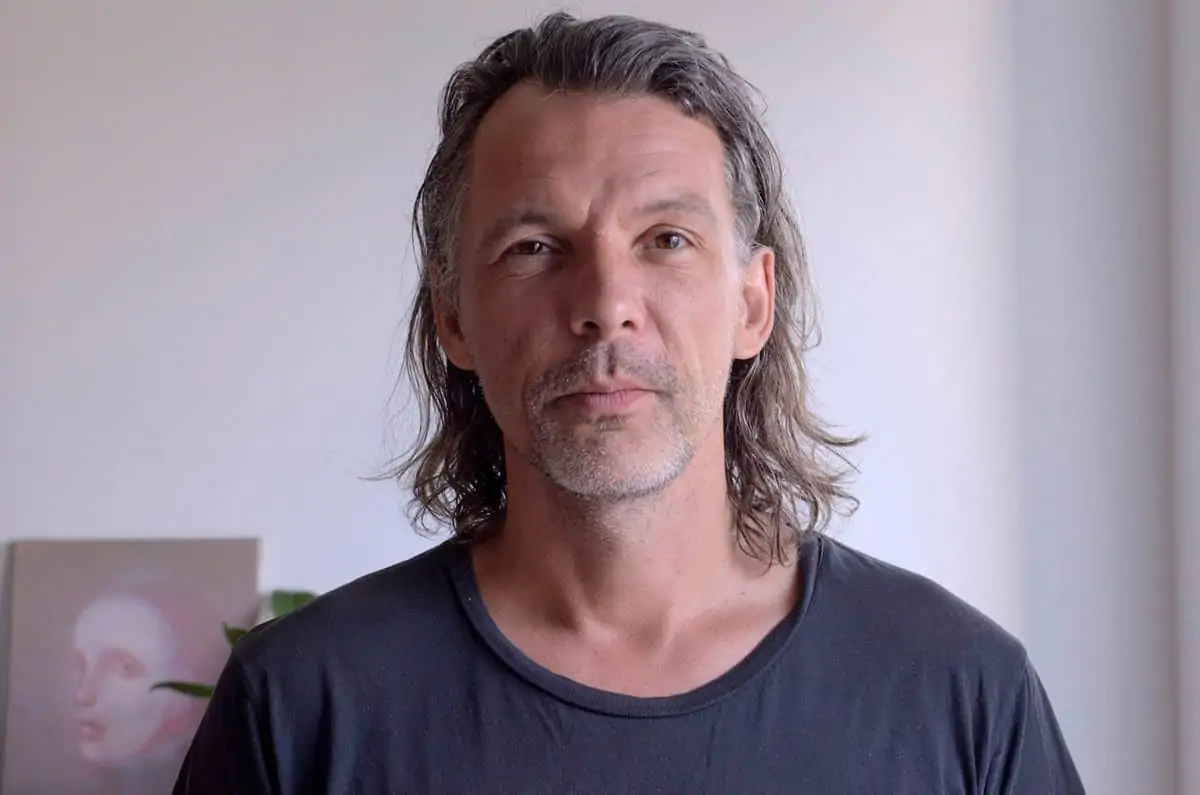

Evoking the time of Vermeer’s 17th century Holland was one of the key challenges facing cinematographer Eigil Bryld and director Justin Chadwick for The Weinstein Company’s historical drama of Tulip Fever. However, whilst the soft purity of the lighting in artworks such as The Milkmaid (1658) and Girl With A Pearl Earring have been the inspiration for many a movie set in that period, and proved a solid starting point this time around, Bryld and Chadwick mentally transported themselves back in time, to imagine what life was really like.

As Bryld explains: “At that time, people would have had peat fires and candles constantly burning, and the interiors and exteriors would have been pretty dense and smokey at times. So whilst we absorbed paintings by Dutch masters like Vermeer, these were more of an initial clue to understanding the environments we would create, light and shoot. Our understanding of what life must have been really like, led us to a concept of what we called ‘dirty lighting’ for this production – with layers of multiple soft-source shadows, mixed colour interior/exterior illumination, lots of real firelight and plenty of atmosphere.”

Adapted from Deborah Moggach’s eponymous novel by Chadwick and Sir Tom Stoppard, Tulip Fever follows an artist (Dane DeHaan) who falls in love with a young married woman (Alicia Vikander), of whom he has been commissioned to paint a portrait by her elderly husband (Christoph Waltz). Set in Amsterdam during the period of tulip mania, the two clandestinely invest in the risky flower market in the hope of building a future together.

Originally, the feature was planned to shoot in 2004, with Jude Law and Keira Knightley as the lead actors, and John Madden directing. However, production was halted as a result of changes in tax rules affecting film production in the UK, and it wasn’t until 2014 that the production got into full swing with a new director and cast.

Shooting took place over 48 days, during June and July in 2014, at Pinewood Studios, where exquisitely detailed sets of the main house, courtyard, tulip traders’ premises and a short length of canal, were built, as well as at Cobham Hall in Kent, Norwich Cathedral, Holkham village in Norfolk, Tilbury in Essex and Kentwell Hall in Suffolk – all standing-in for Amsterdam.

Danish cinematographer Bryld is known for his work in such films and TV shows as Wisconsin Death Trip, which won him the 2001 BAFTA Award for best factual photography, Kinky Boots (2005), Becoming Jane (2007), the highly-acclaimed In Bruges (2008), plus You Don't Know Jack (2010) and Netflix’s House Of Cards (2013), which both yielded him Primetime Emmys. Currently based with his family in New York, where he also shoots commercials, Bryld’s next long-form venture is Ocean's Eight, an all-female spin-off of the Ocean's Trilogy of heist comedies, directed by Gary Ross and set for release in the summer of 2018.

“I had never worked with Justin before, but we had several Skype meetings and rapidly discovered we had similar ideas for Tulip Fever, and I definitely sparked on his ambition, energy and excitement,” Bryld recalls. “We both wanted to respect the period aspect of the story, but did not believe it should be a distant memory or a dusty old costume drama. For it to really come to life, we both thought it should feel modern and relevant, with an engaged camera.

“We discussed the natural light and how it was used in paintings by old masters, and aimed to get the sense of the low sky outside, but with real atmosphere from fires and flames.”

"Although digital gives you plenty of wiggle room on-set, I’m not a fan of tweaking the look day-by-day. I prefer to make any visual changes in-camera, through the lighting, exposure and atmospheric effects."

- Eigil Bryld

Bryld framed the production in 2.35:1, shooting without filtration using ARRI Anamorphic Master Primes on Alexa XTs, which were generally rated at 800ASA. The camera package was supplied by ARRI Rental in London. Paul Donachie operated A-camera/Steadicam, assisted by first AC Jennie Paddon, with Bryld on B-camera, assisted by David Penfold. The gaffer was Mark Clayton.

“Right from the start, we wanted this movie to have a contemporary but epic feeling,” says Bryld. “The obvious choice would have been to use older glass, to render a softer, more poetic result, but I was reluctant to do that as we wanted to have freedom of camera movement to pick up on the detail and textures of the sets and costume, and to keep the look crisp and more square. Older glass can get quite distorted around the edges of the frame, especially on wider-angle lenses, and it is especially noticeable on close-ups. The Anamorphic Master Primes are fabulous lenses that can open up to T2.2, with lots of detail. I was not worried by the sharpness of the image. I knew the smokey atmos would help to subtly soften the image and accentuate the dynamic difference between the youth and maturity of the actors in a kind way. Also, framing in widescreen I could compose for tight, intimate two shots of the lovers, or create a sense of space and an individual’s isolation.”

Prior to the shoot, during extensive camera tests of sets, hair, make-up and costume, Bryld worked with Technicolor in London to develop a single LUT for the shoot.

“I modelled the overall look on a fairly contrasty film stock, and then swung the colour to the cooler side of the colour spectrum,” he explains. “Although digital gives you plenty of wiggle room on-set, I’m not a fan of tweaking the look day-by-day. I prefer to make any visual changes in-camera, through the lighting, exposure and atmospheric effects.”

As for the dirty lighting, Bryld went for multiple soft-sourced shadows, with mixed colour. “I was very mindful of the need to build layers of lighting into the sets, rather than have the light from one perfect side light, and to also clearly differentiate between the different environments in which the action took place. The kitchen, for example is a more pleasurable, homely space, filled with light, whereas the living room has a much more oppressive atmosphere.”

Working closely with his gaffer and the production designer, Simon Elliott, Bryld saw that a range of LED fixtures were carefully concealed in built-in panels, which could be opened or dropped down on hoists as required. To create the appropriate ambience for the different scene settings, DMX-controlled daylight and tungsten LitePanels were judiciously placed in the ceilings in checkerboard formation, supplemented with soft bounce lighting through windows, and real fire light emanating from hearths and candles. Whilst these lighting set-ups delivered a tremendous amount of control, they also helped to support the freedom of camera movement desired by the director, allowing for 180-degree turns and the active engaged style they had originally conceived.

Due to a shooting commitment with Woody Allen in New York, Bryld was only able to attend the DI at Technicolor, with colourist Jean Clement Soret, for a few days.

“Despite the brief time we had together, we got through a lot of the key moments, and I left Jean Clement with the task of maintaining the overall image contrast to keep the sense of shape and volume in the sets. He filled-in the blanks, and think he did a great job.

Bryld concludes: “Tulip Fever is an complex, intriguing story and was certainly a cinematographic challenge. It all came together beautifully in the end, and I believe the story is all the more powerful by having respected that historical period with our approach.”