POP-MOTION

Shot in just six days by a small crew dedicated to their craft, the music video accompanying Peter Gabriel’s “Sledgehammer” is still admired as a shining example of stop-motion success. 37 years after the video’s release, two members of the team reflect on the boundary-pushing process of discovery and invention.

Having garnered an abundance of accolades including the most awards for a single video with nine MTV Video Music Awards in 1987 and later being crowned MTV’s number one animated video of all time in 1998, the video to accompany Peter Gabriel’s song “Sledgehammer” has continued to impress music lovers and those working in the creative industries alike.

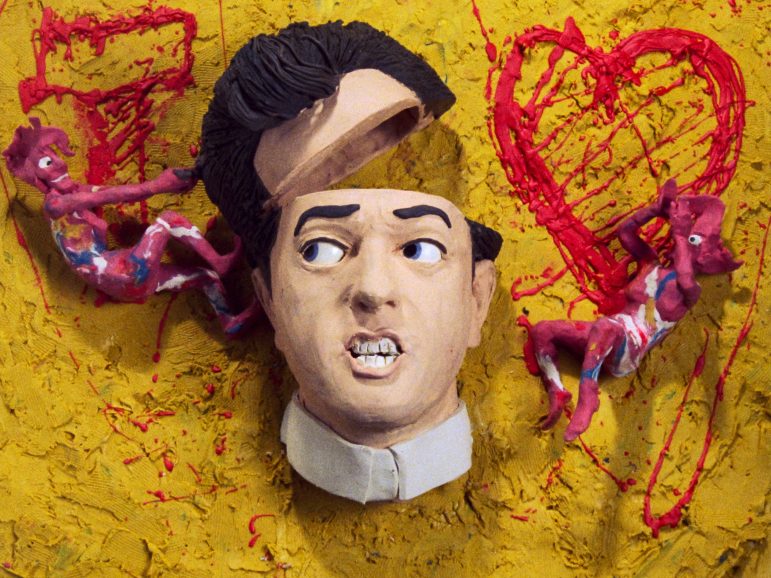

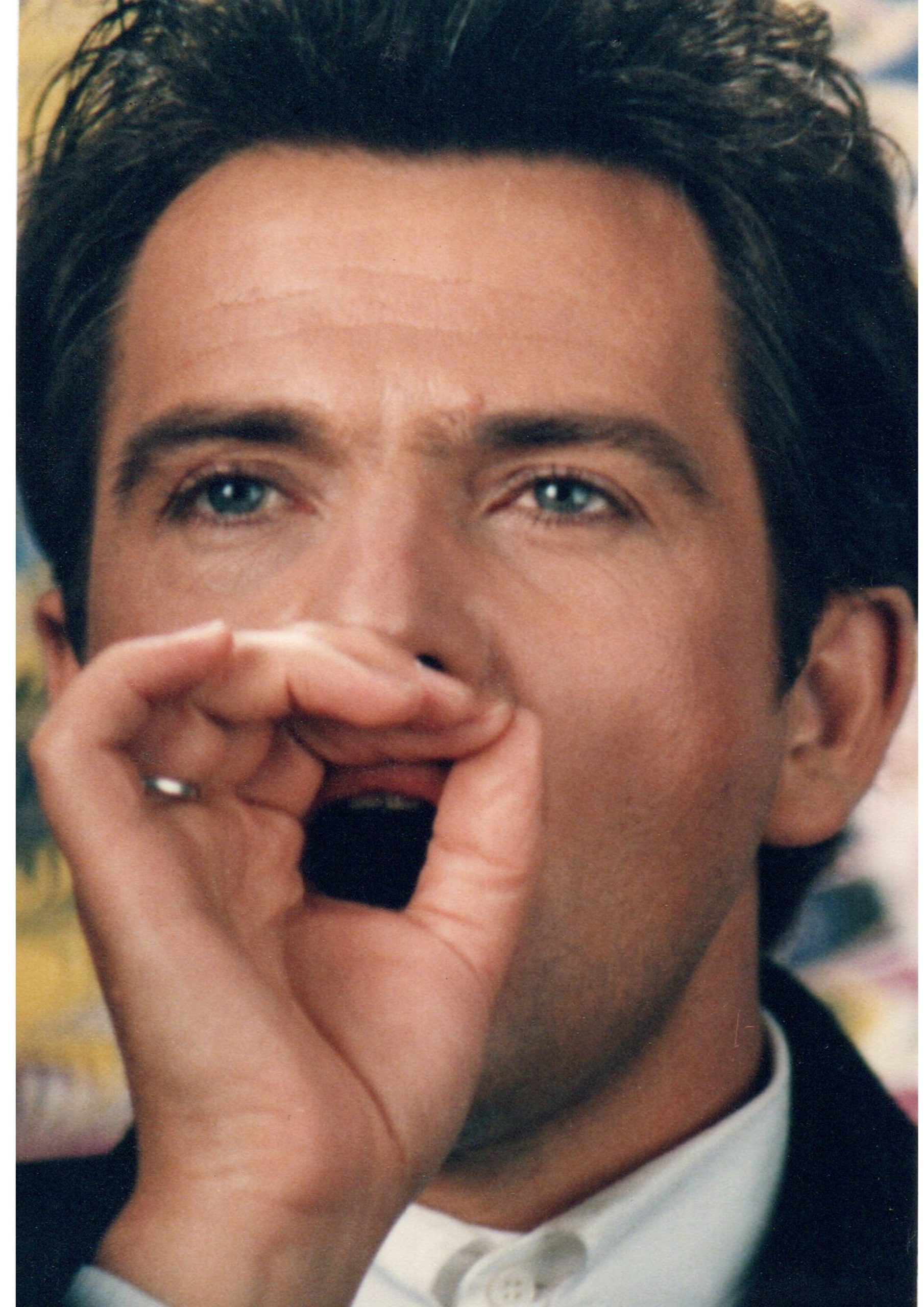

The video’s 1986 release – to accompany the first single from Gabriel’s fifth album So – not only elevated standards in the industry, it has also been a source of inspiration to many ever since. The product of an artistic collaboration between Gabriel, Aardman Animations, the Brothers Quay, director Stephen R. Johnson and a dedicated and talented team of filmmakers, model makers, animators, and scenic artists, “Sledgehammer” features ground-breaking stop-motion, claymation and pixilation techniques. It also required Gabriel to lay underneath a sheet of glass for 16 hours while the action for one of the wild and wonderful sequences was captured one frame at a time. Now that’s ultimate dedication to the craft from musician and crew.

The production marked Aardman’s first foray into the music video world – a creative adventure they were excited to embark on, explains Aardman Animations co-founder David Sproxton CBE who headed up the lighting of “Sledgehammer” as well as being heavily involved in the cinematography. “When the call came to us, we instantly said yes,” he says. “Peter [Gabriel] had seen the work of American director Stephen R. Johnson, who also directed Talking Heads’ “Road to Nowhere” and was keen to work with him too.”

Award-winning cinematographer and stop-motion specialist Dave Alex Riddett BSC (Chicken Run, Wallace & Gromit, Curse of the Were-Rabbit, Robin Robin) was sailing around the Caribbean shooting a documentary when he received the call to join the project. “I’d been away for some time working on commercials, short films, and documentaries and this sounded like the perfect next project,” he says. “I was a fan of Peter, and straight after my documentary ended, I headed back to the UK to work with the Aardman team.”

Prior to heading up the camera and mechanical aspects of “Sledgehammer”, Riddett had some experience of pixilation – a stop-motion technique used to capture some of the music video’s action which sees live actors used as a frame-by-frame subject. “I got into animation initially because it’s the cheapest way to make your own movies if you haven’t got a big budget,” he says. “A colleague Dave Borthwick and I – working as the Bolex Brothers – made quite a few pixilated films because we couldn’t afford models, so we just used real people and got them to move one frame at a time, all shot on a Bolex. My life depended on that camera – it was affordable, reliable and did everything.”

Energy and ingenuity

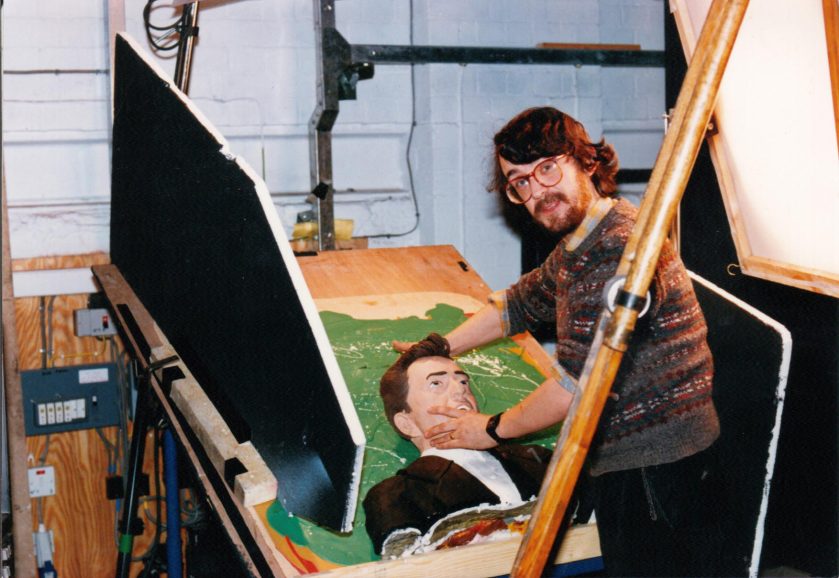

During our interview, Riddett – who has worked with Aardman on a plethora of stop-motion successes – is sat in the company’s studio in Bristol in front of one their first 35mm cameras – a converted Newman-Sinclair on which much of “Sledgehammer” was shot.

Up until two years prior to making the move to the Newman-Sinclair and shooting Gabriel’s video, Sproxton and Aardman co-founder and creative director Peter Lord’s work was mostly shot on 16mm. “This included early work for Channel 4 and series such as The Amazing Adventures of Morph, using the very reliable and versatile 16mm Bolex which many standout series such as The Wombles were also shot on,” says Sproxton.

“But we then shifted into commercial work and needed to up our game to 35mm. Apart from rostrum cameras which were designed to shoot a flat field looking down, only had one shutter speed, and were designed for one lens, there wasn’t really a 35mm camera specifically designed to do stop-motion animation. The special effects cameras were mostly designed for shooting at high or low frame rates.”

The search for a suitable 35mm camera led Sproxton to Bob Sharman, a camera engineer, who had worked with special effects expert, Wally Veevers. Sharman suggested converting an old Newman-Sinclair camera to single frame operation.

“Bob replaced the 200-foot internal loading magazine with a drive sprocket – almost like a Mitchell type drive – and attached a Bell and Howell magazine, creating a complete hybrid, “explains Sproxton. “The camera had a reflex shutter, but we needed a video tap so we could feed that into a tape-based recorder – U-Matic – so the animators could see how their animation was working out. So, Bob attached a low light video camera into the viewing system. That became our prime stable 35mm stop-frame camera for quite some time and captured a lot of “Sledgehammer” and Creature Comforts.”

While the music video was made on “relatively antiquated pieces of equipment”, that was part of its success and charm, says Riddett. “In fact, it’s the old kit, which we still adore, that’s most suitable for stop-frame animation,” he says. “No matter how old those cameras were, each frame was registered beautifully.”

This approach to creating an arsenal of optimal equipment has continued at Aardman – although since 2008, completely digital – where much of the kit is custom built and designed in house, including camera heads that are adapted so they can be motorised and computer controlled to produce smooth camera movements on a frame by frame basis.

“Sledgehammer” was also captured using Mitchell S35 cameras, hired from Joe Dunton BSC’s rental company. These were teamed up with a variety of lenses, including a Cooke 5:1 zoom. Shooting single frame, the cameras captured sequences such as Gabriel in the chair surrounded by a multitude of items and the final scene when he is joined by dancers and extras. The main camera was mounted on the robust Vinten dolly and supported by equally sturdy Moy heads. This set-up was used on most of the scenes except for the scene where Gabriel is surrounded by fruit which was shot on a rostrum camera.

There were no digital image capture technologies at the time to enable easy reference to what had been shot. So, the crew used what Riddett refers to as “quite a crude video assist camera, attached to the camera, looking at the viewfinder graticule”. This image was fed into a low-band Sony U-matic tape deck, which could grab a single frame and allowed the animators and director to see the animation in progress. This single frame U-Matic system was designed in Wales by a company called EOS and was based on a Sony 5850 deck.

Gabriel was shot on several different sets but his head in shot had to be the same size and position in each of them. To assist in lining-up, a previously shot “master frame” of Gabriel was cut from the rushes and inserted behind the camera graticule so the image could be seen when looking through the viewfinder. This allowed very accurate line-up from set-up to set-up.

“So, as I looked through the viewfinder, I could see the image of Peter as well as the image I’d stuck in the graticule and could line everything up. For most of the shoot, that was our reference to keep everything the same. Part of what gave “Sledgehammer” its relatively unsophisticated look was the fact that it was shot on almost “vintage” equipment, with no trickery involved. It was the pure energy and ingenuity that made things work and shines through in the finished piece.”

The final scenes of the video were shot on five cameras and each one was operated independently, there was no way of triggering them all from a central switch. Editor Nigel Ashcroft operated a tape deck which displayed the lip sync for Gabriel to follow. When Gabriel was ready, Nigel would instruct the camera operators to shoot the frame. As the singer mimed the song frame by frame, he needed a reference for each mouth position, so a small monitor displayed a playback of him singing the song a frame at a time.

Fuelling creativity

Filmed in just six days in Bristol at Aardman’s original studio at Wetherell Place in Clifton, and the University of Bristol’s Wickham Theatre, the shoot was a sizeable task to tackle. But with a deadline to meet as the video was due to air on Top of the Pops the following week, the dedicated team were even more driven to produce work that would live long in the memory.

“Six days is not long to create a five-minute animation. Normally a short animated film can take a year or so. So, it was quite daunting, but the way in which we created it in such a short time turned out to be one of its strengths and fuelled creativity,” says Riddett. “It was great because we were normally used to working with small models, but this was a life-size set.”

Turning the ambitious vision into a reality required Gabriel’s face be plastered with emulsion paint in stages, the singer be surrounded with dead fish among other items, and have his hair covered with grease to hold it in place. “We put him through hell, and he was suffering from back problems from needing to remain in position for so long,” says Sproxton. “In the sequence when a train circles his head, the skin on his nose began to flake off where the railway track rubbed against it for hours. It must have been so irritating, but he was a real trooper even when he was uncomfortable.”

Every member of the tight-knit crew – from animators Nick Park and Peter Lord through to model maker Michael Wright and camera assistant Susannah Shaw – shared a love of animation and the process of breaking the action down a frame at a time. Each of the “Sledgehammer” frames captured is a stop-motion masterpiece, bursting with character and colour.

Sproxton and Riddett admit that the striking visuals were the product of a “rather vague storyboard of sorts with an awful lot made up as we went along”. Director Johnson sketched ideas and often adapted them during the shoot. “He wanted a baby elephant at one point,” laughs Riddett. “A real one, and we actually contacted the zoo but of course it wasn’t possible.”

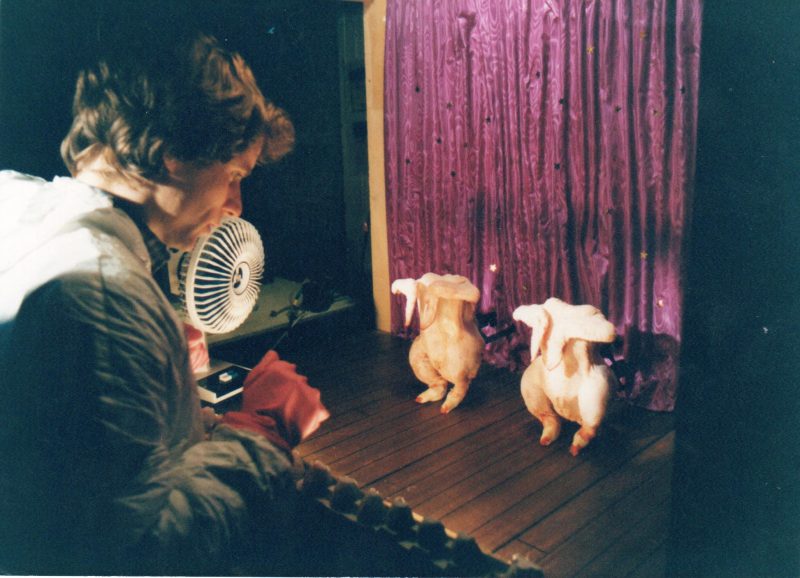

Johnson then changed his mind, instead opting for a chicken which the crew at first assumed would be made from rubber. But Johnson wanted a real chicken, so it was off to the supermarket to buy an oven-ready one.

The resulting unique sequence which sees two dead featherless chickens dancing on stage was animated by Aardman Animations’ Nick Park – animator and creator of productions including Wallace and Gromit, Creature Comforts, and Chicken Run – and shot on an adapted Newman-Sinclair P400 camera (paired with 1950s Cooke lenses) he brought with him from the National Film and Television School in order to complete his graduation film A Grand Day Out. “Nick understood the camera wasn’t very light tight, so between frames, he put a little black cap over the lens and when he was ready to shoot the image, he removed the cap, took the frame, and put the cap back on to reduce light leakage,” says Sproxton.

Master of invention

Aardman’s 2,000-foot studio was subdivided by black drapes to create a space for the dancing chickens to be animated, the main set where Gabriel sat in an old cinema chair, a set for the clay sequence shot by Lord and a set for the ice-head of Gabriel which is shattered by a sledgehammer.

Modelmaker Chris Lyons cast Gabriel’s head in order to create a vinyl mould which would be filled with water and then frozen in a chest freezer. But the freezing process took longer than anticipated. “We only really had one decent ice head and literally could have only one go at it, but then senior technician Glenn Hall who headed up the rigging came up with the idea of mounting the sledgehammer on a pivot so that it would land exactly where we wanted it,” says Sproxton.

In the studio a space was also created for Lord to shoot the animated clay scenes, which featured at one point a character tumbling over a waterfall in a barrel. This was all shot on a Mitchell NC rack-over camera using Baltar lenses. “Those sequences were shot with a locked-off camera, almost like doing rostrum work, and we gave Peter a video assist image by setting up a video camera alongside the film camera,” says Sproxton.

The handiwork of stop-motion animators Stephen and Timothy Quay – better known as the Brothers Quay – also bursts onto the screen. Their distinct style was responsible for memorable sequences aligning with lyrics in which objects interact with Gabriel’s head, from the toy train on a track which was assembled and then shot backwards as the track was removed piece by piece through to fruit enveloping the musician.

Inspiration for the Quays’ fruit sequence came from the extraordinary creations of Czech filmmaker and artist Jan Švankmajer. It was captured at 1/4 second shutter speed and with faster film stock – 400 ASA Kodak 5298 – compared to the Kodak 5248 stock used to capture the rest of the video as the shot needed a good foot of depth of field to keep the fruit on the glass sheet and Gabriel lying on the couch beneath in focus.

To allow the Brothers Quay to animate the objects on top of the glass Riddett fixed a video camera to the rostrum camera to see what the rostrum was seeing. “I literally attached a video camera on the side of the rostrum with a bulldog clip, so I could slip some cardboard in to line it up,” he says. “We had an image the animators could look at which approximated what the rostrum camera was seeing, but it certainly wasn’t state of the art.”

In the same vein of Johnson’s choice to work with a real chicken, the Brothers Quay opted to animate real fish in some shots rather than create models. As the shutter speeds were quite slow for such scenes, not much light was needed, meaning most lights in Aardman’s studio set-up were 1kW or 0.5kW lanterns and rigged to keep in line with Johnson’s desired “fairly flat and colourful” look.

“I put a key light up, shooting through some diffusion material, to keep the shadows quite soft. Peter’s set-up was pretty straight forward – standard three-point lighting and bounce boards,” says Sproxton. “Nick’s lighting for the chickens was slightly trickier because it was a model stage set-up, and we wanted a spotlight effect. As I’d done a lot of theatre lighting, I was familiar with using profile lanterns – projector style lanterns you often see front of house in theatres.”

Sproxton sourced a Strand Pattern 23 classic 1960s theatre lantern which an iris could be placed in and opened and closed with a lever. This allowed him to create a spotlight which would appear on the chicken when the iris opened. “When shooting relatively long shutter speeds – a quarter to half a second – you don’t need 5K or 10K lamps. And when you’re filming chickens, you didn’t want anything too hot, or the chickens would be cooking in front of Nick,” says Sproxton.

Focused on the frame

While filmmakers creating a music video now would likely aim to match the lenses across the focal lengths for colour and look, no lenses were matched when shooting the various sections of “Sledgehammer”. “It hadn’t really occurred to us,” says Sproxton. “We only really used the middle of the lens anyway, so the aberrations you might have got at the edges didn’t matter because we were pretty well stopped down to achieve the depth of field required.”

Unlike more conventional productions, much of “Sledgehammer” was captured at F11 or F16. One of the final scenes – which was shot in a set in Wickham Theatre sees Gabriel joined by backing singers and dancers before extras, members of the crew and Gabriel’s children join him – was shot at a minimum of F8.

The theatre provided the perfect location as fly rails were positioned every foot upon which lights and scenery could be hung. “There were also many lights already in the theatre – mainly 1K and 2K fresnels – and we hired a nine light,” says Sproxton.” The aim was to just saturate the whole scene with soft light. I put a load of the 2Ks on the front of house rails, on one side I placed diffusion material in front of them. They had some modelling but fundamentally the set-up was quite simple, similar to a saturation rig in a TV studio, and with a lot of backlight.”

More cameras were required than previous scenes, with several S35s offering the coverage needed, and a top shot captured by a Bell and Howell. There was a lot of action in the final scenes so the cameras on the studio floor were re-positioned from time to time to capture the action fully. Whereas for the early sequences the camera was locked off, the main camera was panned occasionally during the shot to cover the action, requiring Riddett to quickly calculate how much it should move each frame.

Editor Ashcroft became a form of tape op for the scene, guiding the crew as to what frame number they were about to shoot. He also acted as film editor during the week, piecing the film together on a flatbed editing machine before the negative was put through a tele-cine machine for the final video edit. Lord was able to use a frame-by-frame phonetic break down of the lyrics to help him direct those final scenes. This tied in with the video tape Aschroft was scrolling through.

“There was a lot of liaison between Stephen, Nigel, the dancers and performers on stage, and Peter Gabriel to make sure everything aligned. You’re all thinking in terms of 1/25 of a second for hours on end and breaking it down,” says Sproxton. “It takes forever but it’s exciting as everybody’s very focused on that frame and the next frame you’re about to take.”

When the backing singers and dancers grew a little weary of holding poses, the crew thought on their feet to come up with a solution. “We animated some chairs to move in behind the dancers who could slowly sit down, frame by frame, and be more comfortable,” says Riddett. “That’s part of the joy of it – changing the plans as you are filming. I believe not having a rigid plan helped “Sledgehammer” and opened it up to so many more things.”

New life to a cult classic

The video was shot and then introduced to the world on Top of the Pops in such quick succession that few adjustments were made when the footage was transferred to videotape. “That’s what went out and for years that’s what everybody saw. Sadly, for something that was shot in camera on 35mm film, a pretty poor-quality image went out because it was a PAL 625-line TV image,” says Riddett.

In 2016, Sproxton instigated a search for the 30-year-old original camera negative with the aim of digitally rescanning and reediting it. They found 4,000ft of original camera negative in the Aardman film vault from the shoot.

“That’s 500 feet of film of the music video footage and the rest was test footage which we rescanned in London,” says Sproxton. “That version is high-definition in the best possible way because it’s actual film and is very detailed.”

Bram Tthweam at Aardman completely reconstructed and eye matched the high-definition scan to the original footage and DaVinci Resolve was used to regrade it to match. During the process, questions arose as to whether it should be made to look like the original or like a very high-def scan which would reveal some of the magic behind the video’s creation to the audience.

“They’re delicate questions because what people remember is moderately fuzzy in terms of today’s definition image. What was captured on the negative is incredible, so do we want to reveal how we did it all by showing some of that detail? Do we want to allow them to see the lips that were held in place on the ice head by thread and show every pore of Peter Gabriel’s face?” says Sproxton.

“The restoration of the 35mm neg looked gorgeous, but you could also see the chickens Nick animated gradually degrade, so we removed a little red to make it look less gruesome. But that was all part of it. Stephen Johnson wanted this sense of spontaneity and for it to look like a few people had made it in their garage over a long weekend with things they had found – which was pretty much what happened.”

While achieving such a staggering feat in under a week, the crew endeavoured to capture as much in camera as possible. “That was the aim from the beginning – for everything you saw on screen to have happened in front of the camera,” says Riddett. “I love doing things that way – actually making the magic and seeing the special effects happen in front of you. It’s almost like a theatrical art. We’ve never made anything in quite the same way, and it still stands its ground as being a piece of its time. “Sledgehammer” has a look of spontaneity which is magical.”

The crew were adamant that if it was going to be a handcrafted animated film, it should look like one. “If you were shooting it now, and using all the digital jiggery pokery, it could be put together differently and it would look cleaner and smarter, but it would also be less energised and certainly less organic,” says Sproxton.

“This has been true of Aardman’s later work too. When we made the first Chicken Run film, we were concerned about whether clay models would stand up on a big screen. But we realised part of the joy was seeing the thumb prints in the clay, and the brushstrokes on the sets. Let’s not make it look so smooth and clean that it appears almost CG. Let’s make it look like it’s been animated and crafted and retain that visceral handmade feel.”