FUTURE PAST

Against the bomb-strewn backdrop of the Second World War, a clever pair of sisters, Thom and Mars, are hard at work creating something extraordinary: LOLA. But despite its name, the titular star of Andrew Legge’s found-footage feature is not a woman, but a revolutionary machine capable of intercepting broadcasts from the future.

LOLA offered a fascinating premise that allowed DP Oona Menges to do some cinematographic time-travelling of her own – and have a ball while doing so. “There were cameras that I hadn’t seen for 20 years, so it was like meeting old friends again,” she remarks.

The idea for the black-and-white project was sparked by one of Legge’s award-winning short films, The Chronoscope – although in LOLA, the fantastical machine would look into the future rather than the past. LOLA would equip Thom (Emma Appleton) and Mars (Stefanie Martini) with a unique insight into events to come, both later in the War and beyond. Much to their glee, the sisters can enjoy sneak previews of Bob Dylan and David Bowie’s chart-toppers decades before they’re launched.

Legge enlisted the help of Menges, whose recent work includes The Host and Different For Girls, to help him craft Thom and Mars’ monochrome worlds. She recalls how his “phenomenal” script resonated with her, especially given the current fragile situation of the world and how our activism can turn so easily to eco-fascism. “The film felt like a really timely warning,” she says. “It felt like a film about love at a time in our world when we really need that, and a warning of how ugly we can get.”

Working with a director like Legge was a refreshing experience for the cinematographer. “He has this genuine empathy and love for sororal relations. I’ve not worked with a man like that before. It was really tender how he wanted to portray the sisters, and he’s the father of two daughters himself. I think it was Hopper who said, ‘Great art is the [outward] expression of an inner life in the artist’ – there were all sorts of threads in this film that came together.”

Authentic angles

The Irish-Welsh co-production marked Menges’ first job since the pandemic began and prep commenced in August 2020. A key reference for the cinematographer was It Happened Here, the 1964 alternative history film by the great Kevin Brownlow, Woody Allen’s 1983 mockumentary Zelig, and Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle for Algiers, the newsreel-style war feature, for inspiration. Like these three films, having LOLA feel as authentic as possible was essential to Legge and Menges’ philosophy. “It was amazing how liberating it was having a director that absolutely insisted it had to be real and in-camera,” she remembers.

This ethos of authenticity stretched to choosing era-appropriate kit, from clockwork and sync-sound to motorised and non-sync cameras, all of which were carefully selected to play a specific role in the story. Menges remembers how Legge pushed against using anything modern, even if it was just the camera body, but they also had the film’s budget to contend with. So, the DP headed to Joe Dunton BSC’s camera cornucopia to find the perfect machines.

The workhorse was originally going to be an Arriflex 35BL4, which Menges describes as a tank. “I thought, no matter how old it is, you could drop it and it wouldn’t break,” she smiles. There was also the 16mm Arricam ST (with its three lenses on its turrets) that wasn’t sync-sound; a 35mm Newman Sinclair (reputedly the same one tossed out of a window on A Clockwork Orange); and Legge’s own 16mm Bolex, which would play a prolific role.

Alas, the DP remembers arriving in Dublin as the crew were prepping and finding the BL in chunks on a table: “The one camera I thought wasn’t going to break!” It meant they needed to find sync-sound cameras they could rely on, so they ended up with a modern Arricam LT as A camera and an Arriflex 416 16mm as B camera.

Through the lens

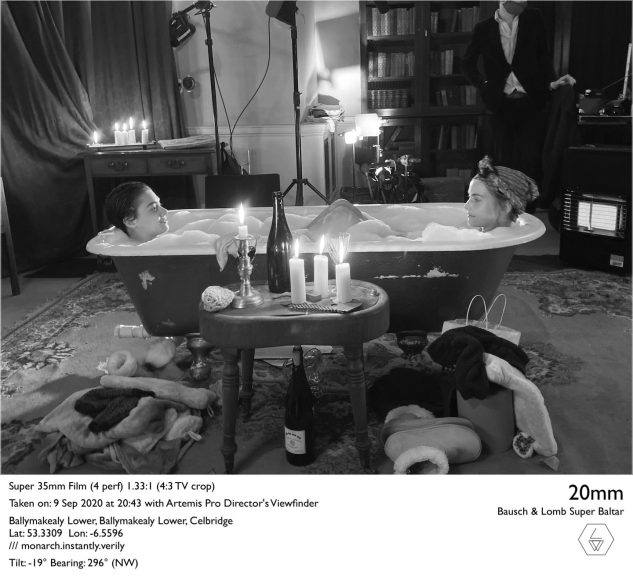

There were seven cameras used in all on the film, complemented by a range of vintage glass, including Cooke Panchros, Bausch + Lomb Super Baltars, and Zeiss Super Speeds T1.3 for the two ARRI cameras, and the Bolex came with an Angénieux. “The three sets of lenses were all producing different looks for different parts of the film,” she notes.

The team sourced archive war footage to emulate in the present-day. While some digital manipulation was required (for Hitler to feature in the film, for example), on the whole, everything was done in-camera. “The big trick was blending stuff,” she says. “A lot of the stuff we were trying to match to was really high-contrast, 35mm stock, so it was trying to achieve that. There’d be other stuff that was looking under-exposed – it would be milky and faded, like it hadn’t been fixed properly. I did a lot of testing to try and explore different ways to reproduce those effects, so we knew how to blend what we were shooting.”

During production, Menges lived in a basement flat at Legge’s house in Dublin and the bathroom was turned into an impromptu darkroom. “We were cooking negative, and we were pulling film all over the place and jumping up and down on it to scratch it!” It was a task the loader had started to do, but he couldn’t keep up with distressing thousands of feet of film before he even managed to load it for the cameras, so Menges and Legge would take the rolls home on the weekends. “These were all the things that as a young camera assistant I was taught not to do, but the great thing was it meant we knew all the ways to get all these things because of our background in film,” she adds.

The stock they settled on was Kodak Double-X, although they had originally wanted to do cross-processing and Ektachrome and “really go wild”, as Menges put it. Pandemic-enforced restrictions, however, meant they had limited options. Cinelab in London was the film laboratory, while Cardiff’s Gorilla Group led post-production.

Turret trick

Legge was keen to keep lighting as naturalistic as possible, with limited film lights. Menges, working alongside gaffer Simon Magee, used the Lightbridge CLRS system. They opted for practicals with incandescent tungsten bulbs, and managed to dig out a lot of ancient film lights from Dunton Cine.

Some scenes, such as a dramatic hanging scene, required a brighter approach. “Back in the day, when they needed such high stops to shoot film, lots of the old newsreel had lights in frame and very harsh light which Andrew was eager to emulate,” she says. “So, there are quite a few scenes that were very harshly lit as we embraced that.”

LOLA herself provided some light, but not without her challenges. “Her projector suddenly dimmed to half the luminosity that there had been when we were building her, but we didn’t have the technicians because of lockdown,” remembers Menges, “so there were situations where our carefully planned transitions (of different handling of the negative) had to be rethought as in low light levels with black and white all the colours tended to reflect the same values – whilst we were embracing the murky look of some old negative throughout the film we had to be careful not to overdo it.”

Smooth operators

In an interesting twist, Legge and Mars’ actress Stefanie Martini also doubled as camera operators. In the film, Mars boasts the very first sync camera, designed by her scientist sister. “When you’re giving the camera to an actor without a video tap you dont actually know you’ve got the shot , and Stef was also trying to perform a part in which it could be considered unfair to lay that responsibility on her , so we built up a huge amount of trust for each other and in the end I was playing Stef’s character Mars’ when I was operating too. We did a lot of passing backwards and forwards, and Stefanie was fantastic – she was quite instinctive with it.”

While a lot of the shots in LOLA were one-take, there were lots of hidden cuts enabled by the choice of camera. One trick Menges recalls was changing the turret on a lens mid shot, which they then shot a plate of so the editor could switch to a different shot and it wouldn’t show.

Working on this project was clearly some of the most fun Menges has had on a production. But did she have a favourite camera? “I love them all equally because they’re all different. They all have their own character – it’s like when you own an old car and it develops a character of its own. They’re like your children – you can’t say you like one better than the rest!”

Comment / Amelia Price, chair, sustainability committee, PGGB