On The Run

John Mathieson BSC / Logan

On The Run

John Mathieson BSC / Logan

BY: Trevor Hogg

Trying to catch John Mathieson BSC, as he heads from Buenos Aires to Los Angeles to London to Bangkok all within a week, is not unlike the pursuit of Wolverine (Hugh Jackman), Professor Charles Xavier (Patrick Stewart) and adolescent X-23 (Dafne Keen) through small-town America.

Thankfully, the chase for the cinematographer comes to a conclusion in an LA hotel room, from where the native of Dorset speaks via mobile phone about his work on Marvel Entertainment’s $127m production Logan. He must be tired as he’s doing the interview after taking part in an all-day DI session on the movie with director James Mangold (3:10 to Yuma, Walk The Line) and colourist Skip Kimball at Technicolor.

A frequent collaborator of Ridley Scott (Kingdom Of Heaven, Robin Hood) as well as an Oscar-nominee for Gladiator and The Phantom Of The Opera, Logan marks the first-time that Mathieson has worked with Mangold. “With Ridley, you have to fly by the seat of your pants,” Mathieson notes. “We work fast, using multiple cameras, and he doesn’t shoot many takes. Jim is the opposite of that. He prefers one camera, lots of takes, and doesn’t move the camera that much. Jim is a straight-shooter. He likes a medium-wide Anamorphic lens. That’s the way they used to make old movies. You didn’t get that far from the actors because the lenses weren’t that advanced, microphones weren’t that good, and directors stood by the camera within earshot of the actors listening to what they said. Of course, Jim was wearing headphones sitting in a tent, but we always had that close proximity to people. Although we did lay track, and had maybe 15 days with Technocranes, we didn’t do big showy shots.”

Mathieson describes Mangold’s desire to shot Logan in the spirit of a classic American road movie “fantastic”, and the pair sought inspiration from a celebrated decade of independent filmmaking. “Jim referenced The Gauntlet (1977, dir. Clint Eastwood, DP Rexford L Metz), Thunderbolt And Lightfoot (1974, dir. Michael Cimino, DP Frank Stanley), and I liked Two-Lane Blacktop (1971, dir. Mont Hellman, DP Jack Deerson). Quentin Tarantino and all of us seem to be stuck in the 1970s. Many of the films we grew-up with have made the biggest impressions upon us. In our late-teens we started noticing things, like photography, moods of films, and different directors. We became aware of how strong those movies were, from Easy Rider (1969, dir. Dennis Hopper, DP László Kovács) to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975, dir. Miloš Forman, DPs Haskell Wexler/Bill Butler)”.

The majority of the principal photography, which lasted for 73 days, took place in New Orleans, with locations including New Mexico and Mississippi. “The schedule was fine. It wasn’t tight. I got there in mid-March and we started at the beginning of May. I had about six weeks of pre-production,” he recalls. “It was great fun being in New Orleans. The studios were fine, and the crew was great,” remarks Mathieson. Andy Ryan was the gaffer, Jimi Ryan the key grip, David Luckenbach – who has worked with Mangold previously – was the A-camera and Steadicam operator, whilst Michael Applebaum operated B-camera.

“However, the exteriors had Tupperware skies, endless flatness, long bright days without much mood, and when you did get the sun it was bang overhead and not interesting,” he says. “You can’t power through it with your 18K. You can black things off, but you can’t change it that much. We did go away to Mississippi, to shoot some cornfields, because we wanted an agricultural background. It’s also very flat. We did some nights there, which were more interesting because I could light them. Going to New Mexico was a godsend because you did get all of these shapes, high specular light, stronger shadows, more contrast and big moody skies. Having said that, it’s not a bad thing to have change in your film. You really do feel that they are moving, as the characters do go through different landscapes, although I would have liked to have done a bit more on-the-road.”

Mathieson continues: “It’s always nicer if one can shoot the exteriors first and do the interiors later. However, we went straight into the studios. That was probably taking into consideration the heat and it being summer in New Orleans. We had to get all of those shots done before we left for Albuquerque, Santa Fe and Chama in Northern New Mexico where the film finishes. That was logistical. You want to be bold enough and do a great interior. You don’t want to do step back and not be as strong but sometimes you can get called-out.”

A solid visual foundation needs to sculpted from the outset by the cinematographer, and Mathieson says, “You’ve got to design it. You can’t do everything in the DI. You can’t do much with greenscreen wherever you are. There aren’t many choices. When you have physical shapes, doors, colours, things for people to walk through and touch, and ceilings at a certain height, you can’t make a magical light come down from a ceiling that looks solid. You keep your fingers crossed and do the best you can. Jim wanted to make a real film in real places with real people.”

An important element for Mangold was doing the driving shots on the road rather than on a greenscreen stage. “When we did them for real the wind comes through the window, and the outside burns out,” explains Mathieson. “I needed to keep that feeling of a hot desert outside. I didn’t want this flat perfect exposure inside and nice exposure outside. We had a camera car, a Technocrane on the back and did a lot of rigs. The film doesn’t have amazing Steadicam master shots or some complicated road shot that goes around and around.”

He says the locations added a great deal to the imagery. “In those parts of the country we were moving through things haven’t changed. It’s very Norman Rockwell there. They don’t drive Teslas but pick-up trucks. It’s Americana. Our characters go to small and de-populated places where they won’t get noticed. They end up hiding within the casinos of Oklahoma City, but have to run again. They drive down small little roads, not freeways. You get a lot of texture, like old brickwork, things falling down, rust and dried-up wooden doors.”

"Everyone seems to want to make everything blue and crush it these days. I’m not afraid of colour. It’s a colourful film with mixed lighting sources. I try to go with what’s in the location."

- John Mathieson BSC

“Although we had two ARRI Alexa XT Plus cameras, it was mostly a one-camera deal,” states Mathieson, who utilised Panavision E-series Anamorphic prime lenses, shooting in 2.35:1 aspect ratio, with some visual effects scenes being shot in 4K. “Alexa is a better camera than most others. I did some stuff on the Sony a7. We also used some 10 to 15-year-old domestic home cameras, as there’s a story within the action where someone is documenting nasty things that are going on in a research laboratory, and we were pretending it was recorded on a mobile phone. The footage had this nice video look. The exposure went up and down, and the focus was hunting. The visual effects people used the Blackmagic camera for their effects shots which were re-photographed off a screen with the domestic camera so they could be cut into the rest of that secretive documentary that was being made.”

Mathieson says he did nothing unusual as regards the lighting. “I had an 18K outside, and 20K inside for the big stuff. For night, I used tungsten Wendy-lights rather than HMIs. There are hard lights on people’s faces, and a lot of contrast. Everyone seems to want to make everything blue and crush it these days. I’m not afraid of colour. It’s a colourful film with mixed lighting sources. I try to go with what’s in the location.”

During production, the second unit was never far behind the main unit. “I was always talking to the director Garrett Warren [who also served as the stunt coordinator] and DP Lukasz Jogulla about what they were going to do next. If you’re doing action it is better to use a couple of cameras. If we were shooting just one camera I would lend the second unit one of our crew members.”

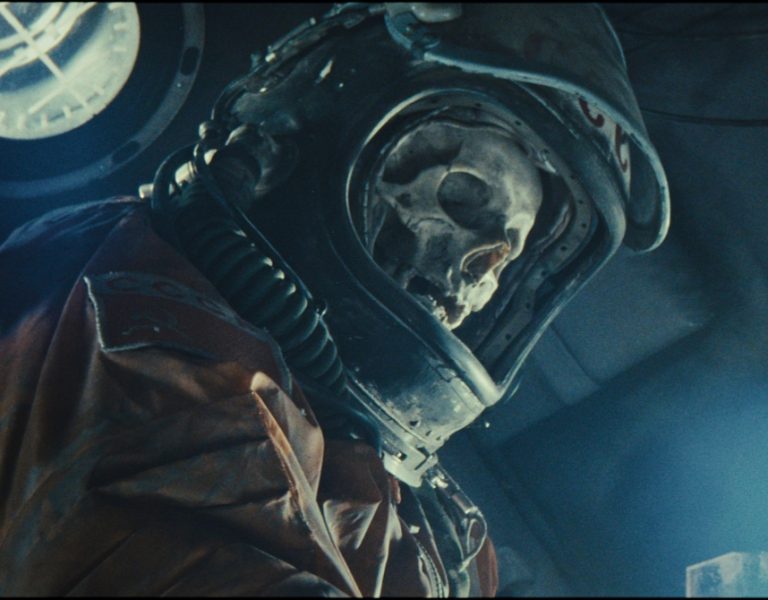

In the movie, Professor Charles Xavier loses control of his telepathic abilities, which Mathieson conveyed visually. “When Professor X has one of his uncontrolled fits, or is threatened or distressed, those around him, including himself, become frozen as he emits a deeply painful sound and an oscillating shockwave,” explains Mathieson. “Chas Jarrett, the visual effects supervisor, asked us to shake the camera, which Dave Luckenbach did quite violently off the end of his Easy Rig. Chas then stabilised the frame by zooming-in taking out the violent movement, but as we had removed the shutter from the camera the image remained fuzzy and oscillating.”

The storyline in Logan sees the aged mutants become the guardians of an adolescent who displays the same attributes of the title character before he reached his full potential.

“Dafne Keen was with us a lot,” states Mathieson. “You always have to be ready to move quickly with a child, because they don’t have the concentration of adults. You have to move at their pace not yours. But Dafne was tough, as long as the day, which was unusual considering the few years she has. Hugh Jackman was ‘on’ every day. He is as long as the day too, and never complains about anything.”

Mathieson says the final cut of Logan reflects the shooting script. “These days some films change totally in the edit, with huge scenes getting dropped and massive reshoots being added. Logan is very much as written. Whilst there are some action sequences, it’s not a cutty film, and was not a difficult film to post. I’m pleased with it.”