Hard Light

Larry Fong / Super 8

Hard Light

Larry Fong / Super 8

At the recent Cine Gear industry confab, held on the backlot at Paramount Studios in Hollywood, a screening of Close Encounters Of The Third Kind (1977) was followed by a discussion with cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond ASC, who won an Oscar for his work on the film.

“What I like about this film is that it’s not perfect,” said Zsigmond. “It still holds up quite well, but what draws you in is a feeling of authenticity, despite the fantastical elements.”

Zsigmond noted that he pushed the film a stop to slightly “step on” the images so that they would be seamless with the many optically done visual effects shots overseen by Doug Trumbull ASC.

Thirty years ago, when those images unspooled before a young Larry Fong, they connected. Fong, who is today a top Hollywood cinematographer, says that Close Encounters Of The Third Kind stayed with him because it featured an ordinary man facing extraordinary circumstances, unlike some other fantasy epics of that era. “It was one of the few times where I felt really transported to that place,” Fong recalls.

Today Fong’s credits include 300, Watchmen and Sucker Punch with director Zach Snyder. He has also photographed episodes of Lost, including the memorable pilot, which was directed by J.J. Abrams, who also helms his latest project, Super 8. The film was executive produced by Steven Spielberg, the director of Close Encounters.

Super 8 features everyday kids growing up in Ohio who by chance film a train passing through town. Something unnaturally powerful threatens to bust out of a train car.

“Super 8 is clearly a nod to those science-fiction films of the 1970s,” says Fong. “It was an opportunity for me to try and emulate that feel and tone.”

Close Encounters was photographed in anamorphic format. Fong’s first step in echoing the feel of Close Encounters was to choose the anamorphic film format.

“Flares were also an important aspect of our look,” he says. Anamorphic lenses produce flares in a characteristic way. “There was never really a question – anamorphic is what J.J. loves anyway, and that’s how his past two films were done.”

Abrams’ two previous feature films were Mission: Impossible III and the very successful reboot of Star Trek. He also directed and created television shows such as Alias and Lost.

The production of Super 8 was mounted for about five weeks in West Virginia, which stood in for Ohio. There were also nine weeks of work in the Los Angeles area, including time at locations and on sets at studios in Playa Vista.

Hollywood Rentals provided the lighting and grip equipment and services on Super 8 (which had a working title of Darlings). The company worked closely with crew and production to meet its challenging budget and demanding schedule. The Playa Vista facility, managed by Raleigh Studios, is a sister company to Hollywood Rentals. This studio and Hollywood Rentals are no strangers to large Paramount features. In fact, Super 8 was produced at this facility simultaneously with another popular Paramount film, Transformers: Dark Of The Moon, due to be released in 2011, in some cases entailing the productions to schedule themselves around each other. In all, Super 8 required the delivery of over a dozen 53’ truck loads of equipment to their sets.

Bits and pieces of the home movies made by the kids show up in the film, and the entire piece plays under the end credits. These images were shot with smaller gauges – Super 16 and Super 8 – to retain the right lens characteristics and depth-of-field.

Second unit cinematographer Bruce McCleery created black-and-white military documentary footage which, in the story, was shot at Area 51 in Nevada. According to legend, the military hid alien life forms and other secrets there. A Super 8 camera was borrowed from Pro8MM in Burbank, who also did the transfer using an HD scanner. Fong and McCleery used the same film stocks that were loaded in the 35 mm Panavision cameras: Kodak Vision3 500T 5219 and Vision3 200T 5213.

“The 5219 seems to be one of the best stocks yet,” says Fong. “We pushed it a stop for all the 35mm night scenes, because we needed the stop with the long lenses. We did a test, and it looked great. The grain holds up. I wouldn’t have minded more grain. I’m not afraid of grain at all.”

In fact, Fong found he had to boost the grain a bit on the Super 8 and Super 16 material. “It’s incredibly sharp,” he says. “The registration was bad, of course, but the transfer techniques now are excellent, so grain wasn’t really an issue.”

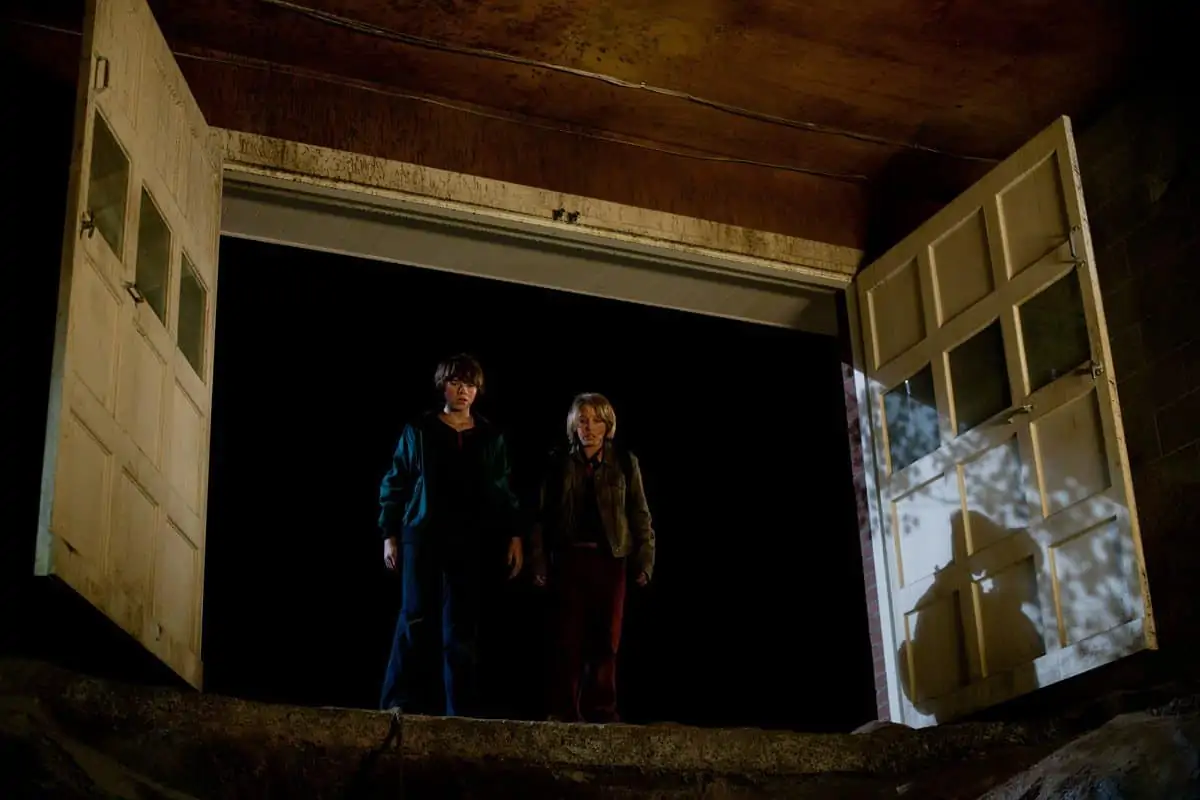

Hard light was another key aspect of the look. “In learning to light with hard light, you really learn to appreciate the skill of the cinematographers who came before us, like Vilmos, and what they could do,” says Fong. “With hard light, you have to pay more attention to the angle, and to the eyelines, and it’s less forgiving in some ways, because it’s more specific.”

"In learning to light with hard light, you really learn to appreciate the skill of the cinematographers who came before us, like Vilmos, and what they could do."

- Larry Fong

Fong notes that Abrams thrives with a spontaneous approach, and he adds that shooting anamorphic doesn’t hamper that in anyway.

“I’ve been interviewed for movies where the director says they have to shoot with HD or digital cameras because the camera is smaller, and they’ll get more done,” he says. “I say that once you put the mattebox on, and the monitor and the zoom lens, and the person who is always connected to the camera, the difference in size is only a matter of degrees. How does that get you through five more pages a day, or trim a week from the schedule?”

Fong finds the aesthetics of image creation much more engaging than the technical aspects, which he sees as a means to an end. “I have good friends in our field who are obsessed with technical things,” he says. “But that’s not why we get paid, and that is not what makes the movie memorable. For Super 8, I knew in my head how the movie should feel, and even if it wasn’t technically accurate, it was right.”