Emmy nominees weigh in, a DP finds his way back to the director’s chair in time to blow up a sand quarry, and another DP deploys a sometimes-overlooked camera on the feature film side.

It’s all happening in this month’s column, if we can keep from wandering too far past our word count!

We were gratified to hear from several of the nominees in the Emmys’ cinematography category. Or rather categories, since readers know they’re broken down into various iterations such as multi-camera half hour series, single camera hour series, outstanding work in a limited series or anthology, nonfiction/reality programming, etc.

We will put aside any Society of the Spectacle-like discussion about what “reality” means, in this context. Though really, it might not ’t be so different than what Lenny Bruce was trying to convey to the titular, and marvelous, Mrs. Maisel, about the walls he tries to break through to meet his audience, and shake them up a little, in the “How Do You Get to Carnegie Hall?” episode of the lauded series. Cinematographer M. David Mullen ASC finds himself nominated once again for his lensing (having won twice previously in the one-hour single camera category for his work on the 60s-set show).

The whole series – as judged by its numerous above and below the line nominations – is humming along at such a high level, we asked Mr. Mullen, what was it about this particular episode – its subplots moving implacably towards the terrific recreation of Bruce’s midnight Carnegie Hall concert – that drew Academy favour?

Mullen says, “the episode visually builds towards this blizzard by the climax — in the background there is often snow falling — so it benefits from the tension and mood created by this limited story time frame of two days. Within that time, there is a wide variety of scenes, from the musical number “Femininity” (a Cabaret-like scene at a burlesque club where Rachel Brosnahan’s Maisel is working) to the Lenny Bruce performance at Carnegie Hall to a sold-out room, that gives the episode some scope.”

Luke Kirby just keeps getting better in the Bruce role, and this episode, recreating the concert held in the middle of that blizzard, may be the culmination of his work in the show.

The storm also meant some changes for Mullen: “Since it is always snowing in this story, for once in the series, I never had any warm sunlight coming through any window — in fact, I played most of the daylight on the cold and soft side, which is unusual for us. For the hospital night scenes, we had a large exterior courtyard seen outside the windows that required key grip Charlie Sherron and his crew to build a huge tent over the top because we were on a daytime shooting schedule. Even though the park lamps in the courtyard should have been tungsten to be period-correct, I had gaffer Jenny Scarlata use daylight LED bulbs in the fixtures so that the snow falling outside always had a bluish tint to them.”

As for capturing those bluish tints: “Our show has stayed with the Alexa Mini with Panavision Primo lenses for almost everything, though we did once shoot a dream sequence on the older PVintage lenses wide-open at T1.4. However, that sequence did not remain in the final cut. For the blizzard sequence, I used an older Tiffen fog filter rather than the Schneider Hollywood Black Magics we normally use. The fogs have a bluish hazy glow that I felt enhanced the snowstorm.”

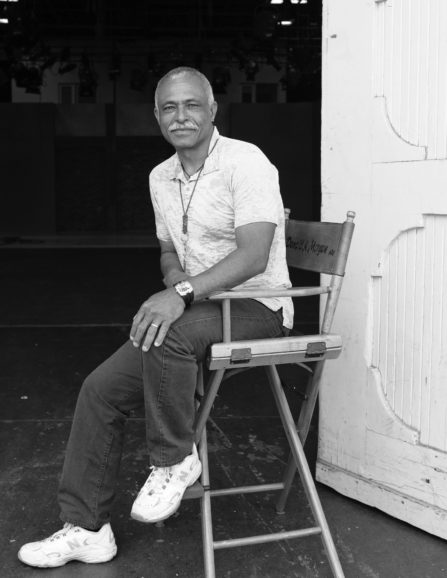

MORGAN’S MUSINGS

Stormy conditions – both meteorological and viral – were also a consideration for Donald A. Morgan ASC, whose annual observations and quotes at Emmy time have practically become a tradition for this column. Morgan finds himself nominated again, after 11 previous wins, in the multi-camera series category for “The Wedding of Dan and Louise” episode of The Conners.

He mentions the complexities of “shooting around Covid, (though) we did pretty good.” The episode itself had a wedding theme. “There was a storm brewing on the way to the chapel. We set up a stage next to our normal one with wind, lighting, and rain! It was a driving sequence with five people in one car, then they pull up to a storm chaser humvee with four people in it, and then they have dialogue between the two cars. When they get to the chapel, they get a tornado warning and the windows get blown out during all that.

“Shooting four cameras throughout all these sequences,” he adds somewhat understatedly, “was a challenge.”

And on the subject of multiple challenges, DP Christina Alexandra Voros talks about the six cameras often used for her nominated episode of 1883, “Lightning Yellow Hair”.

The show, from creator Taylor Sheridan, is a prequel to his highly successful Yellowstone, telling of the cross-country, covered-wagon trek that eventually brought the Dutton family to their mythic, park-adjacent ranch spread.

Voros, like fellow nominee Ben Richardson ASC, also shot episodes of Yellowstone, and – like Richardson – directed them, too. Indeed, she wore both hats – or sat in both chairs, for “Lightning Yellow Hair” as well.

Talking to us from the set of Yellowstone, where she was busily at work on the upcoming season, Voros noted that since essentially the same crews were doing both shows, there was a “tremendous shorthand…such a fluidity and seamlessness the way the team works together.” She mentions her ACs, gaffer, and key grip, and how she not only leans on them, but has always “welcomed a deep level of collaboration”.

She notes that “in a weird way, it gave me more time,” as a director, to work with actors on character, movement, etc. She also observes that in many ways, there were fewer of the usual series lighting demands in the prequel since “it’s a world of sprawling daylight exteriors,” where sunlight shapes the scene, rather than “creating it with electricity”.

Moving through that sunlight, in concert with the horses, wagons, and hopeful pilgrims, were Alexa Minis, sometimes as many as six to capture the action, as she “was thinking toward the cut as I was shooting”. Also, given the tornadoes, stampedes and shootouts in this particular episode, a way to make sure all the necessary action was captured, since, as she once reminded a producer, “horses don’t hit marks.”

Affixed to the Minis were Summilux lenses, or sometimes Fujinon Premista zooms. With the vistas they were shooting “we live very much on the long ends of the lens,” she notes, and it was “not uncommon to shoot through a doubler.”

Ultimately, Voros says, “it was kind of a symphony of everyone’s excellence at their job. That both Ben and I were nominated speaks more to our crew, than it does to ourselves,” as she describes the series as “a team of artists and technicians working at the highest levels under ridiculous circumstances. I think that’s what makes me happiest about the nominations.”

EXPLOSIVE IDEAS

If keeping track of horses in tornadoes keeps with this column’s theme of directorial and DP challenges, so does blowing up a demolition site for a climactic sequence – even before the rest of the scenes on that location were filmed.

So it was for Paul Cameron ASC on the latest season of HBO’s Westworld. Cameron famously shot the series pilot (on film – a medium the show still uses) for creators Lisa Joy and Jonathan Nolan. He frequently collaborates with the pair, having shot films for Joy, and shot – and also directed – subsequent episodes of the series.

For season four, he returns solely to the director’s chair, for the recent “Generation Loss” episode, which features (spoiler alert!) a pivotal forward time jump on which the rest of the season hangs.

The climax for that episode, ostensibly set on the outskirts of a 1920s-era, prohibition and gangster world providing AI-enacted entertainment along the lines of the original Western, Roman, and other lands, was actually shot at New York’s Hudson Yards. And involves explosions that envelope some pivotal characters.

“I pitched the idea to blow it up first,” Cameron says. “The second take is the one that appears in the episode,” which he describes as a “practical explosion with CG dressing”, which also describes the series approach (and evidently a kind of Nolan Brothers philosophy) to FX in general.

So they “blew it up and shot a lot of the gun battle the first night”, concentrated the second night on fine-tuning the gunfight (that narratively precedes the explosion) and, somewhat astonishingly, “completed the sequence in three nights”.

The prepping began about a month ahead, when, Cameron says, “you get a kind of outline,” for the episode you’ll be doing, while “waiting for a script.” And then, “you get the script (and) you see the challenges that lie ahead.”

He was able to meet them in collaboration with DP Peter Flinckenberg, who he describes as having “a very particular style, and a very particular look”, which also “melded very well” with the work of the series’ other cinematographer, John Conroy ASC ISC.

That melding was also important as Cameron was “one of five directors shooting that day” in the Hudson Yards, with “actors going back from one set to another”. He also thanks the actors, like Tessa Thompson and Aaron Paul, who worked with a “shorthand that carried them through a very rushed sequence” which included another of Cameron’s early pitched ideas: “an idea about this stylized lighting and circular camera movement” in a shed, adjacent to the explosion.

Both help underscore the revelation for Paul’s character, as it increasingly ‘dawns’ on him about the years he suddenly realizes he’s lost, and the transformed world his character now inhabits.

Cameron, meanwhile, is quite enjoying the world he now inhabits, describing it as “a very positive time” as he focuses predominantly on directing while “getting close to some big projects” that can’t quite be revealed yet.

But he also remains available to help Nolan and Joy, when asked. “It is,” he opines, “nice to still shoot.”

BLACKMAGIC MOMENTS

Still shooting himself, after starting in production design with the cult favorite Bubba Ho-Tep from the Elvis-and-mummy infused Joe Lansdale story of the same name, is Daniel Vecchione who returns to collaborate with director Diego Ongaro on another indie feature. This one features rapper Freddie Gibbs in a compelling turn as the fictive Money Merc, himself a famous rapper who take a Thoreauvian retreat to a country house in the Massachusetts woods, to try and get past a creative block – only to find he may be reined in by other aspects of his life he’s never previously confronted.

The setting, and some of the now-supporting characters here, were previously seen in Ongaro and Vecchione’s first collaboration, Bob and the Trees, which had its premiere at Sundance.

One of the most unusual aspects of both films is that they were shot with Blackmagic cameras, those ultra-affordable-yet-rarely-deployed-for-features “pocket cinema” cameras that come in 4k, and now 6k flavours.

“The original Blackmagic Pocket Cinema Cameras with late 70s/early 80s era Nikon glass, was an extremely small camera footprint,” he says, making it perfect for that first feature. “After some testing, we decided to shoot Down with the King on two Blackmagic Pocket Cinema Camera 6Ks since they still wanted a very intimate set.

“Connor Lawson was the B-Camera operator, and we had two first ACs and a media manager. There was no G&E department in keeping with Diego’s desire to have more people in front of the camera than crew behind it. The PCC6K’s weight, 13 stops of dynamic range, and the dual base ISO of 400 and 3200 made it a very appealing choice. I leaned heavily on the 3200 ISO for the post sunset blue hour shots that are featured heavily in the film, as well as the night interiors which were lit solely by practicals.”

Capturing the mood-inducing lights were “Atlas Orion Anamorphic lenses, and we used the 50mm, 65mm, and 100mm the most. I really wanted to shoot anamorphic because I thought it fit Money Merc’s character. I wanted the audience to feel something quietly epic and luxurious in the cinematography, and the lens choice with the 2.39:1 aspect ratio really helped with that.”

He adds: “it was a dream to premiere this film in the ACID Section at Cannes.” (Which, however hallucinatory the films may be or not, refers to the French acronym for the Association for the Diffusion of Independent Cinema.)

Meanwhile, the relationships between the lead characters in HBO’s Insecure had also grown increasingly diffuse, as the show entered its final season. In capturing some of that in the college reunion-themed premiere, “Reunited, Okay?”, Ava Berkofsky ASC found herself with her third Emmy nomination in the single camera half-hour series category.

“I’m especially excited to be nominated this year among such exciting DPs,” she told us. The HBO-heavy category also includes Barry, Hacks, Netflix’s Russian Doll, and others. “In terms of being nominated for Insecure for a third time, I’m hoping the academy is responding to the evolution of a look that stays true to its core intention, but has hopefully gotten more bold and nuanced. The show itself got both bolder and more nuanced and I just wanted to keep challenging myself to keep taking those risks visually- especially this being the final season.”

Bold yet nuanced is about as good as a dichotomy gets, bringing up the very contrasts of light and shadow that are, ultimately, the two poles upon which all the work we strive to report on here, rests.

And we’ll see you again somewhere between those axes in about a month. @TricksterInk / AcrossthePondBC@gmail.com