THE ROAD TO FREEDOM

Ambitious 10-part Amazon series The Underground Railroad sees James Laxton ASC and Barry Jenkins unite once again, this time to tell a powerful story rooted in the history of the American South and atrocities of slavery. Cinematography with a unique tonal quality and authenticity documents courageous Cora’s epic journey as she fights for her freedom.

Filmmaking is like a dialect, according to James Laxton ASC. In the same way people who grew up in Texas or London speak the same language, but with a different accent, he believes the foundation of film is based around creative “accents”. “Barry [Jenkins] and I learned our visual language in the same place and at the same time when we were at film school together, so there’s an accent in our filmmaking that comes from that shared experience and references,” he says. “Our conversations about filmmaking feel effortless because we’re coming from the same place.”

Since their first meeting at Florida State University, the talent and shared visual language of cinematographer Laxton and director Barry Jenkins have created inimitable productions with powerful imagery and messages that live long in the memory, from their 2003 student short My Josephine through to critically acclaimed and award-winning films such as Moonlight (2016) and If Beale Street Could Talk (2018).

The pair’s latest production of epic scale and ambition, The Underground Railroad, is an adaptation of Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 2016 novel. The real underground railroad was established in the US during the mid-19th century and comprised of a network of people and safe houses that offered help and safety to African American slaves from Southern plantations, whereas the alternate history novel reimagines the escape network as a rail transport system and focuses principally on the journey of Cora and Caesar as they strive for freedom by escaping the plantation where they have been enslaved.

“Often, I will catch wind of something, or Barry will whisper something to me years earlier – it always starts as a casual conversation. Just after we shot Beale Street in early 2017, he began mentioning this project and asked if I wanted to get involved. The book is incredibly inspiring and visual, so off the bat you start thinking about a cinematic language for the series and what it should feel like emotionally, creating a visual blueprint,” says Laxton, who read the book before the script, which Jenkins co-wrote.

“Like any project with Barry, it’s an organic process that began with speaking loosely about the approach. When the script came a few months later, we talked more specifically about the camera, format, and lens choices.”

The Underground Railroad marked Laxton and Jenkins’ first television series and it was clear from the outset that 10 episodes rather than a feature film would be necessary to do the expansive journey and multitude of characters’ narratives justice. “To compress the novel into 90 minutes would cut too much out,” says Laxton. “The chapters that follow Cora’s travels from state to state are very episodic and lent themselves to a series which then required us to think about how to adapt the camera language to suit.”

The scope of the story being told and the way it symbolised part of American history made the production take on a different meaning to projects Jenkins and Laxton had previously collaborated on. “Rather than learning new facts about American history, those lessons became personal in a way they hadn’t before,” says Laxton. “It was important to experience that, and I wanted to be a part of giving that to audiences. As a filmmaker, you take in information and funnel it through your own personal, creative processes.”

Each episode, or chapter, of the Amazon series explores a different stage of the journey, some moving backwards or forwards in time and homing in on different characters’ experiences. To differentiate between episodes, each one adopts a distinct visual language. As Cora’s journey takes the viewer somewhere new with each experience, the cinematography also needed to change which saw the filmmakers draw from multiple references.

Cinematically, a significant influence was Andrei Tarkovsky’s post-apocalyptic sci-fi Stalker (2005) about travellers searching for fulfilment. The creative impact of that journey can be seen most prominently in the first episode. Photographic inspiration was drawn from Australian photographer Bill Henson, whose “haunting” style of night flash photography Laxton admires and had an “eeriness” he felt appropriate for elements of the series, which at times, especially in combination with the tension-filled soundtrack, enters the realms of horror.

The first example of this effect in action is the night-time party in episode one when a boy is whipped for spilling wine on a character’s shirt. The scene cuts to slow motion close-ups of violence with the intention of creating a “heightened sensibility”, drawing from Henson’s flash photography.

His influence was also pivotal in “The Great Spirit” episode. “We even called it the Great Spirit light as it symbolises the characters’ spirits. The idea of incorporating flash photography also came about because in early history some Native Americans did not want to be photographed because they believed it would steal their spirit. I thought we could reference this through flash photography, inspired by Bill’s work.”

Embarking on the journey

Eight months of prep were dedicated to the ambitious series, during which time the filmmakers decided to shoot the entire production in Georgia rather than in multiple states. Traveling to places such as Ohio and New York during location scouting, taught them valuable lessons and allowed them to accumulate colour palettes and ideas about how to capture the different seasons through conversations with 1st AD Liz Tan, the producers, and production designer, Mark Friedberg.

“Due to the role I play within Barry’s collaborations, I’m invited into the process earlier than I might be by other filmmakers,” says Laxton. “It’s a great benefit because those conversations can happen over a longer period opposed to a four- or six-week prep. I was appreciative of this luxury and I think it played a critical part in the way the show looks.”

When embarking on the project, Laxton admits he felt quite daunted by not having attempted a production of this scope with so many locations and large sets. Only select scenes were storyboarded, including complex stunts and effects sequences or the pivotal slo-mo scene of two characters falling from a rope ladder which was shot with Phantom high-speed cameras against blue screen.

“We created a shot list for the first couple of episodes but largely speaking, the rest was not shot listed. The idea of going in without a shot list terrified me, but in the end Barry and I really enjoyed the experience,” he says. “We came up with ideas naturally on the spot that felt very appropriate, without having to sit in an office and drum up a list that may or may not be applicable once the actors are on set. I must also thank our incredible crew, including critical collaborator, A camera operator Jarrett Morgan. He always walked on set in the morning and came up with an approach that felt appropriate to the scene and the blocking Barry had done with the actors.”

Although the 116-day shoot, which began in September 2019, was cut short in March 2020, luckily, the crew were only three days away from wrapping and picked up the remaining scenes in July. Around a third of the series was filmed in Savannah, Georgia, with the latter two thirds in Atlanta. Many of the interiors were sets, including the home interior and attic in the “North Carolina” episode and the saloon in “Tennessee Proverbs”.

The tunnel which two of the characters fall into was shot on an Atlanta-based soundstage with a high ceiling as it was important to capture the characters physically fall, safely on lines, for around 50 feet, as opposed to suspending them while they acted as if they were falling. This required extensive blue screen rigging and a huge set comprising a large blue screen behind the characters, wings either side, a ceiling, and a pad underneath because the scene was captured from multiple angles. “We also worked with a great visual effects team led by Dottie Starling, who did a fantastic job, especially on that scene which was one of the biggest effects sequences,” says Laxton.

The filmmakers endeavoured for the world the series explores to be largely captured in camera rather than relying on visual effects to create elements such as the trains. “Mark [Friedberg] did a lot of work figuring out the best approach to use real trains. As it would be difficult to get a train to a soundstage, we built a 200-foot-long tunnel around a private railroad in a train museum in Atlanta. It was amazing they let us do it and it allowed us to safely shoot actors on real trains without relying on CGI,” says Laxton.

A look that was true to the period was realised through a fruitful working relationship with Friedberg, who Laxton met on If Beale Street Could Talk. Conversations also explored how practical lights could be best built into sets and which LED sources would match the colour temperature of gas-powered lights of the period.

Different perspectives

Having enjoyed shooting with ARRI Alexa systems for many years on a variety of productions, Laxton opted to capture his first series with the Alexa LF and LF Mini. “It’s almost like a film stock which Barry and I are in love with,” he says.

Most episodes were shot on spherical glass and 16:9, with three episodes that contextualise the journey and offer a backstory – “The Great Spirit”, “Fanny Briggs” and “Mabel” – adopting a different visual language and shot anamorphically. “Lenses and format seemed like the right way to go to provide a different groundwork for those episodes opposed to shooting handheld,” says Laxton.

With guidance and insight from Panavision’s Dan Sasaki, Laxton selected the most appropriate lenses to suit both types of episode. “I worked with Dan for weeks, tweaking and changing the lens flare profiles, coatings and bokeh to create a custom look. I was so happy with the end results – Dan augmented a set of the Panavision Primo 70s for the spherical episodes and the T Series for the chapters we needed to shoot anamorphically.”

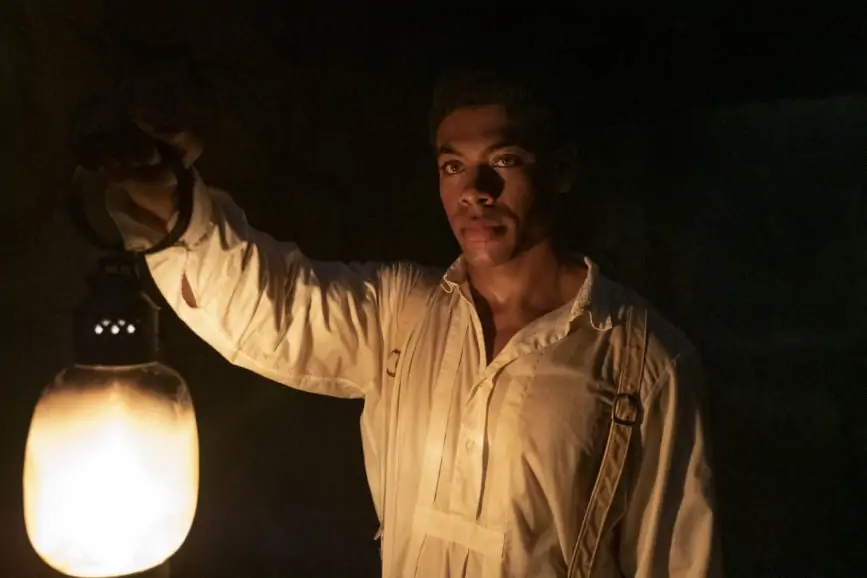

The series focuses on the history of the American South and slavery and the characters looking back at the audience can have a really powerful impact in that storytelling.

James Laxton ASC

While Laxton and Jenkins’ collaborative process has remained the same since they met, each time they take on a project, they attempt to explore a new creative direction that is appropriate to the material. “You see that in Moonlight and If Beale Street Could Talk – the material is different and the aesthetic changes, which I hope is also true for this series,” says Laxton. “We adjusted our visual language; it takes on an eeriness. There is a kind of floating camera that can be seen in our previous work but is much more emphasised here through longer takes and camerawork that moves through spaces in an almost haunting way. Growing up in America, we’re haunted by our past which that symbolised.”

Laxton and the crew were mindful not to exaggerate the trauma or portray the violence in a gratuitous fashion through their camerawork. “The story we were telling is based on truth, but we wanted to avoid using many handheld shots or adopting a documentary technique. We wanted a different tonality, so there is more Steadicam and crane work to create the pace and tension we were looking for.”

Jenkins and Laxton’s conversations often turn to the topic of perspective. While the series includes traumatic scenes, they believed the sequences would have a deeper meaning if they were photographed from a specific character’s perspective. One example of this use of perspective in the visual storytelling is seen in a night-time scene when Cora is being whipped and the camera begins in a high angle wide shot and jibs down, panning away from the violence and finds Caesar watching.

“We felt it would be a personal depiction rather than a gratuitous, dramatic, or violent one,” says Laxton. “Of course, it will still be difficult to watch, but it will come from a place that wants to tell a truthful story but not emphasise the violence for the sake of it.”

As can be seen in the pair’s previous films such as Moonlight, The Underground Railroad employs the technique of characters looking directly at the camera, sometimes set up in poses similar to traditional portraiture and other times featuring a group of people who follow the camera with their gaze as it pans. “The series focuses on the history of the American South and slavery and the characters looking back at the audience can have a really powerful impact in that storytelling. As an audience member, you can feel judged when you’re being stared at by a character,” says Laxton.

“There’s a lot to unpack in those shots, but for me they’re about the characters asking the audience for something – for their time or to be conscious of what they’re watching – or looking at them in an accusatory way. There’s a build-up of energy and emotion so those shots also almost diffuse that and act as a breathing point.”

Shallow depth of field also helped to “transport the audience into the characters’ minds and experiences”. “We wanted people to really get sucked into Cora’s journey as opposed to just witnessing it, so to bring audiences into a character’s perspective we isolated them through framing or shallow depth of field,” says Laxton.

The story we were telling is based on truth, but we wanted to avoid using many handheld shots or adopting a documentary technique. We wanted a different tonality, so there is more Steadicam and crane work to create the pace and tension we were looking for.

James Laxton ASC

Wide shots were used to convey the magnitude of the trauma and violence. “The scale of the slavery in the US was huge – it was a machine; it was an economy and we depicted it in a wide shot in sequences such as those seen in the first episode of the men and women working in the cotton fields. The rows upon rows and infrastructure of it felt like it needed to be depicted in that wide sensibility,” he says. “And in the scenes where the men and women are hanging from the trees, the wide shots convey this was not just a small, isolated thing; these atrocities happened on a massive scale.”

Pivotal points of the characters’ journeys were also captured through top shots which Laxton believes can be “quite a judgmental perspective of an action,” but also like “taking a breath to understand the scale of the story being told. That’s the power of the book, the script, and hopefully the show – to visually represent quite intimate aspects of the characters’ experiences through close-ups, but at times go for top shots that provide scale.”

Certain sequences called for bespoke rigs to be built. Shots in the swamp in the first and last episodes saw a DJI Ronin 2 attached to a custom-made floatation dolly that was pushed along the surface of the water. To shoot in the crawl space that features in the North Carolina episodes, a small, bespoke, low-profile rig – similar to a “four-wheeled skateboard dolly” with a remote head – was created by key grip Michael Price. “This could move around on the floor, meaning I could be next to Barry but still operate a camera to capture all kinds of shots, almost fishing for different angles.”

Incorporating nature in scenes such as these was crucial, from “the interactive and immersive feeling of the swamp” through to conveying the heat in the cotton fields through sweat on characters’ foreheads or the clothing they wore. “All these natural elements needed to find their way into our frames,” says Laxton. “It was not easy to work in those environments but that made the images we captured feel that much more authentic.”

Grounded in truth

One of the most challenging locations to shoot was the train tunnel, partly due to the infrastructure and safety precautions that must be considered when working with moving trains. Many scenes in the tunnel also took place in the dark, other than occasional candlelight, which was difficult, especially when shooting close-ups of characters exploring the spaces.

“We wanted it to feel genuine,” says Laxton. “I always want to feel grounded in reality and real spaces, which for me are motivated from real lights. Trying to figure out how to do that in the absence of light was hard.”

Complex infrastructure and rigging and an expert team of electricians helped achieve the creative ambitions. “Gaffer Kiva Knight, who I’ve worked with for a very long time on Moonlight and Beale Street, was fantastic and led our lighting team when rigging all the LED sources in the ceilings of the tunnel set to give us a soft quality that is controlled in terms of dimmability and colour temperature.”

The rig comprised around 40 2×4 and 4×4 LiteGear LiteMats, built into the sets and hidden by headers the art department created to look like support beams which allowed the characters to walk freely through the tunnel. This same set-up echoed through most of the stations, except for Tennessee which included gas-powered lanterns because the stations become more modernised as Cora travels further north.

Another notable lighting set-up was utilised for the large night-time exterior in episode one – a party scene which required a series of large HMI rigs surrounding the slave quarters which were the size of two football fields. “We then added closer units – one of two 4×4 LightGear LiteTiles LED fixtures and rigged 20×20 soft boxes with 28 LED Astera Titan Tubes to provide a closer source of soft moonlight, coloured blue with a hint of green. This was the formula for the moonlight colour for the whole series.”

Although If Beale Street Could Talk was set in the 1970s, Laxton’s latest production was his first experience of shooting a period piece set so early in history. Previous films he shot had a base light of ambient city streets, but The Underground Railroad’s large exterior scenes were environments devoid of streetlights and motivated from natural sources such as the moon or candlelight. This candlelight was sometimes created by real candles, but occasionally incandescent tubes were placed in lanterns carried by the actors, with flicker gadgets offering control over how they would flicker and interact with the environment.

Authenticity and a truth in the images were of utmost importance, meaning exterior daytime lighting was almost always natural, occasionally introducing some sort of bounce such as muslin. “Relying on the sun to do what it does naturally made sense to achieve a truthfulness of image with integrity. We didn’t want to just put up a big screaming backlight behind a character that seemed unnatural. As so much of our camera language was based around seeing 360-degrees at any given time – we’re moving the camera from one actor to the other, and then turning around to see what someone is reacting to – half the battle was avoiding the director’s monitor being in frame as well as the lighting equipment.”

Unique tonal qualities

When filming a story that spans multiple states in a single state, working in unison with the art, costume and locations departments helped find solutions that would enhance and emphasise each point in the journey. “Using a different LUT for each episode was also key, as was making sure changes were made in the DI to enforce the different stages of Cora’s journey,” says Laxton. “Whenever there was a flashback, we returned to the original colour palette as opposed to keeping it within that episode’s palette to retain that integrity and preserve the idea of how she remembered it.”

The series saw Laxton and Jenkins collaborate once again with colourist Alex Bickel (Moonlight, If Beale Street Could Talk, Ladybird). “He’s such an important member of the team and because of that relationship we do so much work in pre-production, making it more straightforward in the DI,” says Laxton. “Except for a couple of episodes which we switched up a bit, what you see in the final version is the LUT we used on set.”

Those decisions – made early on as opposed to reimagining a new colour palette in the DI – were based around a look and feel that reinforced Cora’s experience. Each chapter had a unique tonal quality, from the muted, homogenised greens enhancing the eeriness of the “South Carolina” episode, which was based around a smaller spectrum of colours, through to “Indiana Fall” where the spectrum widened and more variety was seen in the skin tones.

A scene within the episode that follows – “Indiana Winter” – has a special significance for Laxton not only for its tonal quality, but also for the role it plays in the story when further enhanced by the soundtrack. “The night-time fire-lit scene is a celebration focusing on the love between some of the characters. It’s accompanied by ‘Clair de Lune’, a beautiful piece of music which we also played on set during the filming of that scene,” he says. “There’s just a catharsis to that sequence and something special about that moment after the many horrors that preceded it. Cora has done and seen so many things on her journey and that scene felt like a breath was being taken.”

Taking time to step back and take a break from the hard-hitting and upsetting aspects of the series’ narrative during production was essential. Amazon recognised the experience would be hard for not only the audience but also the cast and crew, so they hired a therapist who was on set throughout. “If someone felt uncomfortable or overcome with emotion or a sense of trauma, they were invited to speak to the therapist which was wonderful. Many people took them up on that and stepped away if it became too much,” says Laxton. “Not everyone might be ready to hear the story and there could be some viewers who also need to take a minute to step away at points as the cast and crew did on set.”

The cinematographer highlights that the production would have been impossible without the incredible energy and work ethic of the crew working in every department. “I had to rely on them in a different way to when working on previous independent and lower budget films. They all did so much, from gaffer Kiva Knight, key grip Michael Price, A camera operator Jarrett Morgan, focus pullers Warren Brace and Alan Newcomb or 1st AD Liz Tan who played a key role in the success of the series and was the spirit that helped us through some of the difficult moments,” says Laxton.

“Sometimes it can be a battle when the budgets are tight which can impact on the schedule. One of the most significant skills this project gave me, which didn’t have those restrictions, was an ability to relax and rely on people when I needed to. The work I’m happiest with in the series are the parts when I was clearly supported in a way that allowed me to be free and trust my instincts and equally to allow other members of the team to express themselves.”