Monster Mash

Remi Adefarasin OBE BSC / Pride and Prejudice and Zombies

Monster Mash

Remi Adefarasin OBE BSC / Pride and Prejudice and Zombies

BY: Ron Prince

Pride And Prejudice And Zombies is Lionsgate’s hotly-anticipated romantic-comedy-horror movie, based on Seth Grahame-Smith’s 2009 novel of the same name, but written for the screen and directed by Burr Steers. The story mashes-up Jane Austen's classic 1813 novel Pride And Prejudice with elements of zombie fiction.

A mysterious plague blights 19th century England, and the land is overrun with troublesome undead. The feisty heroine Elizabeth Bennet, played by Lily James, is a master of martial arts and weaponry. Uniting with Mr Darcy, played by Sam Riley, they aim to rid the English countryside of the deadly nuisance, and in doing so just might discover true love. Ron Prince caught up with cinematographer Remi Adefarasin OBE BSC to discover more about the production and his creative work.

How did you get involved with the production of Pride And Prejudice And Zombies?

RA: Sue Baden-Powell, the executive producer, who I worked with previously on Cemetery Junction (2010), was looking for a collaborative cinematographer who could work with the director Burr Steers. It’s always best to meet in person if at all possible, but Burr was in LA. So Sue set up a Skype call and we got on very well. Burr, who also wrote the script, preferred to leave decisions about how to shoot scenes to the cinematographer. Anthony Minghella was the same when we did Truly Madly Deeply (1990). I very much prefer this to directors who like to “prove” that they know everything and can lead the unit up a blind alley. Burr concentrated on the story and the performances.

What appealed to you about Pride And Prejudice And Zombies?

RA: I haven’t made a version of Jane Austen’s Pride And Prejudice and would worry about doing the 1813 novel one more time. This film holds tightly to her story and stays period, yet the characters are living in an England that has been infested with the undead for a very long time. There are obviously twists and turns that reveal the freshness of the classic novel.

When you first discussed the look of the movie with the director, how did you envisage the film?

RA: Burr knew straight away that it shouldn’t be a spoof. Characters would never nod to the audience. For the characters it was really happening. When we got together in pre-production we both agreed we didn’t want a bland look, yet we didn’t want to push it too far either. We wanted to create a world you could believe in, yet push the imagery just that little bit further. We agreed that it shouldn’t have a faux desaturated look, and we didn’t want to heighten the saturation either.

What research did you do? What creative references did you look at?

RA: I make it a point not to look at any film that is about the subject I’m about to work on. So, I didn’t look at any versions of Pride And Prejudice, nor any zombie movies. It’s all too easy to watch DVDs around the subject and you end up with a film that is a copy of someone else’s vision, often itself borrowed from an older source. It’s best to shut your eyes and dream-up your own world. To focus on the look for this movie I centred on the work of painter John White Alexander. His use of light is both natural yet magical. I was also inspired by John Atkinson Grimshaw, another amazing painter.

Was there a film vs digital debate? How did you decide on the origination format?

RA: Because of the amount of VFX work, with around 420 VFX shots, and the overnight production of VFX show-and-tell temps, it was clearly favourite to shoot digital. I love film as it is so flexible and always looks good. With digital mediums you have to work harder to give the film an interesting look. Often digital movies are ruined by going too far with the look. With digital work I feel that the backlight has to be minimal, same with accent lighting. I also have this method of using a very, very fine dark brown net that I stretch over the lens (with an ARRI-made holder). I shape a custom hole in this fabric and the effect is to cause a softening and diffusion to the edges of the image.

"To focus on the look for this movie I centred on the work of painter John White Alexander. His use of light is both natural yet magical."

- Remi Adefarasin OBE BSC

Tell us your creative and practical reasoning behind your choice of cameras, lenses, lights and grip?

RA: We decided the best aspect ratio would be 2.39:1 and to shoot open gate on ARRI Alexa cameras. Alexas are friendly and reliable with an impeccable sensor. We used Cooke S4 primes with Optimo 24-290mm zooms. We also had two Alura Zooms, 15.5-48mm and 30-80mm. We shot 2.39:1, open gate, to get a larger image area and also more height top and bottom to allow VFX to steal bits of tree/wall etc. Sometimes they need to clone a bit of an image to cover up mechanical aids to the settings. Also, although we didn’t need it, they could use the extra frame area to stabilise the image. I’ve had a very long relationship with ARRI Rentals and asked to use them as supplier. They keenly support every requirement and are happy to make adjustments or customise equipment if needed.

My gaffer, Jimmy Wilson, has a good relationship with Panalux. We used conventional heads, but made great use of LED technology, which is leaping ahead. My philosophy is that fewer lamps can produce a greater image – not under lighting but not getting multiple shadows by having too many heads with conflicting angles. It can so easily look fake, even on a zombie movie.

What was your approach to the camera movement?

RA: We used a more classic approach to the cinematography – regular dolly moves and some Steadicam shots. My A-camera operator Julian Morson is also a fluent Steadicam operator. We didn’t use much handheld, but when we did it was for a reason and we didn’t give it the extra twitch, which drives me mad when done without reason.

And was your approach to the lighting? And what lights did you use?

RA: Heightened realism was the intention. Neither bland flat light nor downward pointing pars. I aimed for images that were striking yet believable. This wasn’t a red and green gel film in the Hammer style. We used LEDs more than normal to bury lights in unusual positions to add just a sheen or a glimmer in hard-to-get-at places. For example, in the crypt of the church there were many zombies. Since this was a real location it was tricky to light, so the LED’s small profile allowed them to be buried amongst the actors. Some larger interiors benefitted from small LED kicks. I have to admit that the colour reproduction of LEDs is always slightly skewed, so I avoid them on shots of leading actors’ faces. There have been a few space movies recently that use LEDs extensively in the spacecraft, and I often think the skin-tones of the cast could look a lot better.

How much time did you have for prep/pre-production? Where were the locations?

RA: My first Skype call with Burr was on 23rd July 2014. I met with my A-camera operator on 1st August, and the shoot began on 24th October. I had twenty days prep, but these were non-consecutive, so it was a lot longer really. I had a good rapport with designer David Warren and was able to travel to help select our locations. We shot five-day weeks on continuous days and could have stayed at that pace for many more months. The shoot was only 43 days, which was tight considering the scale of the film. We always had two cameras and I operated the B-camera.

We only used a studio on the final day for a few hours. The whole film was shot on locations that were very precious – including West Wycombe House, Hatfield House, Syon House and Basildon Park – so all teams had to take extra care not to damage priceless objects. The rigging of lights was very limited in most locations.

What were your main concerns during the shoot?

RA: My main concern was that each day we had a bit too much to shoot, yet we hoped for a high standard and didn’t want to let ourselves down. We were shooting at the end of the year when the light was beautiful but didn’t hang around for long.

Who were your crew?

RA: The camera crew were brilliant. Julian Morson was my A-camera and Steadicam operator, and Alan Stewart the second unit DP. Jimmy Wilson was my gaffer, with John Arnold our key grip, who was ably supported by Charlie Wall. My B-camera first and second assistants were Leigh Gold and James Perry. Our camera trainee was Katy Ruffy. The DIT was Joshua Callis Smith. My son, René, was 1st AC, with my other son Ben the 2nd AC. René first worked with me on The Hollow Reed (1995) after studying filmmaking. John followed, and then Ben. It’s a good relationship and, like the rest of our team, few words are needed in either direction to convey thoughts.

What part does risk-taking play in your work, if any?

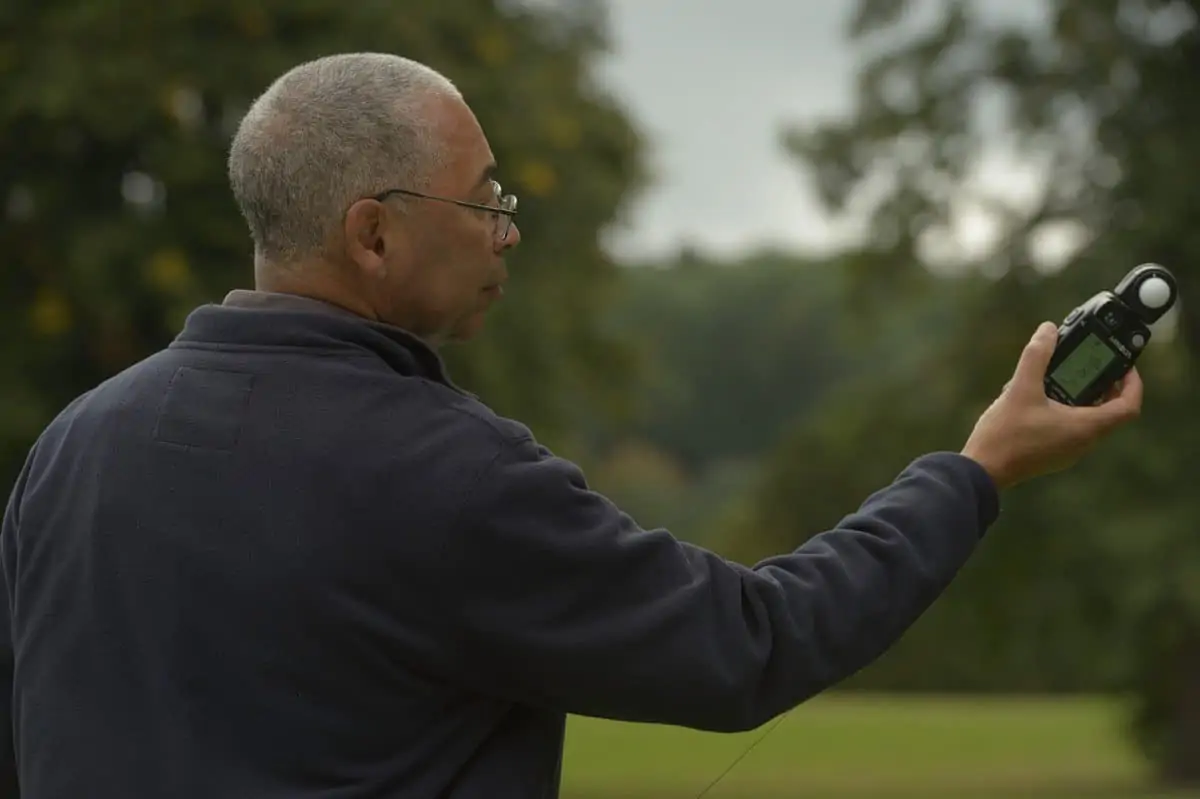

RA: With beautiful film, every shot is a little risk. With experience you know pretty much what you will get when printed. To get bolder, braver images you have to trust your experience, your eye and your meter. In the digital world the result is shoved right under your nose. “Is that too bright?” “Should we be tighter?” “Is that too dark?” The imagemaker can become part of a committee and not the leader. Sometimes more energy is spent defending the vision than creating it. If we had all the time we would like, there would only be one camera. Coverage would be limited and we would never take extra shots just in case they might be needed. In the real world you often find you have to use two cameras, just to get the day done! I like operating the B-camera as the A-camera gets the main vital shot and the B picks up more dangerous bonus images. If I operate the B-camera I know how far I dare go without spoiling the film.

Were there any happy accidents, unexpected things that worked out well?

RA: The cast were mostly very young and came with a fresh talent and knowledge of filmmaking. They all worked very hard and without fuss or complaint.

How did this movie challenge you/push your skills?

RA: With a tight schedule and limited daylight hours during the winter shoot, you had to know where you were heading. There just wasn’t time to change your mind.