HATCHING A FRANCHISE

When Derek Vanlint CSC passed away in 2010, obituaries called him the “Alien cinematographer”. With the help of David Johnson BSC, we look back at the film that defined Vanlint’s career.

Released in 1979, Alien forever changed what sci-fi could look like, sparked a long-running franchise, and established Ridley Scott as a director to watch. Yet for Derek Vanlint CSC it was something of an oddity in a lifetime of shooting commercials. “My experience with feature films was very limited,” he wrote in American Cinematographer. “Alien was to be my first big feature.”

“Derek and I did many commercials together – in the region of 100,” says Scott. “You name it, we did it. Derek and I were a perfect match because I was an operator and he was an ace with his light meter.”

Based at Shepperton in the summer and autumn of 1978, Alien was shot with two cameras, Scott manning a Panaflex while Vanlint operated a Panavision SR. Loading the SR was a young assistant named David Johnson, who would one day be a BSC member and – 25 years after his work for Vanlint – the cinematographer of Alien vs. Predator.

“I was lucky to get the job having recently worked with Adrian Biddle [later BSC] on a commercial,” Johnson recalls of the original film. (Biddle, then a focus puller, also went on to shoot a sequel, Aliens, and many other blockbusters.) “No-one knew we were working on a project that would have such a profound long-term existence and become a franchise in which, in future, I would play a part.”

Before Alien, cinema tended to portray spaceships as sterile environments. Scott, Vanlint and designers Mike Seymour, John Mollo and H.R. Giger changed all that with dark, dingy corridors, blue-collar characters in Hawaiian shirts, and a bio-mechanical xenomorph straight out of a Freudian nightmare.

“Derek and Ridley established this dramatic, low-key, backlit look together and kept it going,” says Johnson. “I think it required a lot of courage from Derek’s point of view, because he was way outside his comfort zone, which at the time was shooting commercials with heavily diffused lights and lenses. I know from experience that it’s sometimes hard when a director has such a strong visual eye because you’re often pushed hard in a direction you aren’t necessarily comfortable with. But Ridley Scott seemed to know exactly what he wanted, and Derek had to come up with the goods.”

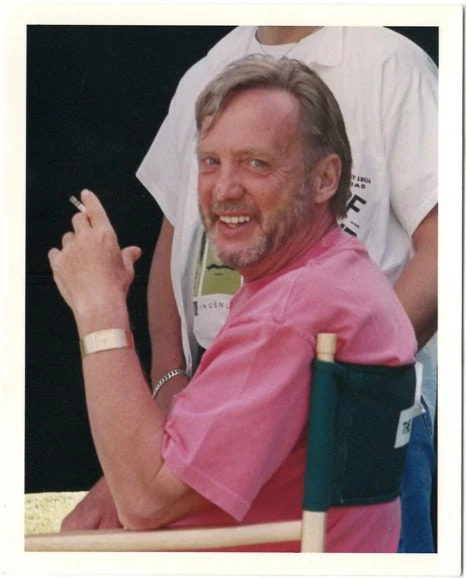

Derek was a master of low-level lighting and suggested the light of the set become the source of the light for the celluloid. Derek had built for himself a lighting desk from which he could raise or lower the source to accommodate the star. Genius!

Director Ridley Scott

Vanlint clearly adapted well, as Scott today attests that “Derek was a master of low-level lighting and suggested the light of the set become the source of the light for the celluloid. Derek had built for himself a lighting desk from which he could raise or lower the source to accommodate the star. Genius!”

The filmmakers frequently used flares, strobes, and smoke to obfuscate the frame, forcing the viewer’s imagination to fill in the gaps, adding both to the horror and the believability. “In those days, smoke machines were bee guns,” notes Johnson, “and we would arrive on the stage to a strong smell of incense which made it feel like we were going to work in a cathedral.”

Another method of keeping the frame alive was scissor arcs, “which in those days were garden shears with carbon rods attached which would create a DC arc, lots of sparks, noise and smoke, and were very dangerous to look at without welding goggles. But the effect they give is pure drama, especially combined with the anamorphic flare and bokeh from the C Series primes.

“Adrian and Colin [Davidson, B camera 1st AC] were under constant pressure to provide rock-solid support with knuckle-biting precision to their focus marks,” Johnson continues. “The film stock was 100 ASA Kodak 5247 and the lenses were wide open at T2.3.-2.8.”

“I still think Derek used to squeeze more out of an anamorphic lens than anyone else,” Scott opines on the DVD commentary. All this despite Vanlint claiming not to be a technical DP, describing his process as “put it up, look at it and light it”.

An iconic moment finds John Hurt’s Kane abseiling into a vault full of alien ova. “The egg chamber had a laser beam effect providing a membrane protecting the eggs themselves,” Johnson states. “This was fairly early in the evolution of lasers in film, and you can see where the bee guns were placed under the beam of light. It looks like the skin of a bubble.”

But this disturbing scene is a mere set-up for the movie’s most indelible moment: Kane’s blood-soaked demise as the alien breaks through his ribcage. When the dailies were screened, “I remember Ridley Scott asking the audience if anyone thought it looked a bit like Monty Python as the chest-burster scuttled across the table. I wanted to throw up,” Johnson admits.

Vanlint’s own response was equally visceral, as he afterwards wrote: “I went out and was rather ill — and I was ribbed quite a bit about that for the rest of the picture.”

“It was a truly fantastic experience working on that movie,” Johnson reflects, “every shot being tailored with great care and respect. Every moment of participation with Ridley, Derek and Adrian was an education. I couldn’t have been more spellbound. That the film spawned so many sequels and prequels is a testament to the integrity of the original.”