Just one language - visual language

Across The Pond / Mark London Williams

Just one language - visual language

Across The Pond / Mark London Williams

By the time you read this in March - which side of the "Ides" you find yourself on - the Oscars and award season itself will be, as previously noted, further in the rearview mirror than usual.

This is mostly due to Oscar having gone on an earlier-than-usual date in February, putting more daylight between it and our top-of-the-month column. So - busy now making sure your hands are thoroughly and frequently washed - you may no longer be thinking of Roger Deakins' cinematographic storm through award season, Parasite's surprise win, or anything similar, as your attention turns to more immediate questions: Not just the hand-rinsing, but when does the ramp up to Emmy nominations start? (Well, now, actually).

And given those larger considerations outside the normal purview of this column, other immediate questions would concern some of our usual round at spring shows like NAB and Cine Gear, but will there still be a "NAB," as least as we've known it, this year, or will larger "existential exigencies," to coin a phrase-of-the-moment, make themselves known?

The NAB has already sent out a press release saying, for now, their show will go on (as did the Olympics), though events like Disney+'s European press launch in London has been canceled, the Hong Kong filmart delayed until August (at least), along with other cancellations and postponements. Deadline is keeping a good running tab of these, but "stay tuned," as they used to say on the TV side of things, before binging and season-long episode drops existed. Perhaps, if nothing else, streaming will be further ascendent if more and more people wind up being shut in. Studios may even have to finally tinker with online "week of release" availability of feature films, if this keeps up.

But we get ahead of ourselves. A little.

Back on the feature side, though you know about Mr. Deakins' taking home Oscar gold, what you may not know is that they only gave him time for two questions in the press room, before ushering him off to the front of the house again for the broadcast. We here at BC got to be one of those questions.

What did we do with our allotment of 50% of all queries for the Best Cinematography winner? Well, we asked, essentially, if he had a "Plan B" for shooting 1917, if ARRI hadn't come up with the Large Frame Mini about a year earlier than planned? What was his backup camera?

He chuckled and said, essentially, he never had one: "I knew they would come up with it. I mean, I've worked with ARRI for so many years - well, all my career, really. So I got a sense that they were going to make a Mini version of the LF. And we went - (my wife) James and I went to Munich and we talked to Franz (Kraus - then the managing director) and talked him into making it about a year earlier than he intended. That was all."

All, indeed! To paraphrase Mel Brooks, it is good to be Roger Deakins! Especially when you need cutting edge equipment earlier than reckoned on.

As for the other 50% of his questions, one of our colleagues noted how many different types of film Deakins had done over his career, and what was it that excited him about this film? To which he answered: "The subject, you know, the subject and working with Sam again, frankly. You know, I've done three films with him (Revolutionary Road, Skyfall, and 1917) and they were all - they were three great experiences. So, yeah. That and World War I, you know."

And with that, he was off his seat in the front.

But the name of Mr. Deakins, CBE, had come up the day before at the Independent Spirit Awards, as well. That would also be due to your humble correspondent, who asked the winning cinematographer there, The Lighthouse's Jarin Blaschke (who'd also been nominated for an Oscar), about the kind of aesthetic he and longtime collaborator, director Robert Eggers, were after - especially as they seemed to be tacking toward the opposite technological end of the spectrum than many of his "full frame," digitally-minded colleagues.

One of whom, of course, would win the Oscar the next evening. Blaschke - shooting on B&W 35mm Kodak film, and using an aspect ratio not generally seen since Fritz Lang's M - allowed that he'd recently "had the honor of meeting Roger," and that it "felt strange" to have such a distinctly different working methodology.

Blaschke talked about getting out of film school and seeing people "spend lots of time coming up with clever LUTs," - a "clever LUT" being a turn of phrase that could only come from a DP - but allowed that "whether it's (easier) coverage, or simplicity in lighting, that's what (he and Eggers) are after.

Besides Blaschke's doff of the cap to Deakins, there were other shout-outs to DPs during award season. Noah Baumbach, whose Marriage Story won him Indie Spirit's best screenplay award ("I kind of hate writing - I love other people's writing") and his ensemble the Robert Altman Award, specifically thanked Robbie Ryan for his collaboration on the project. And the next night, in his acceptance speech as best supporting actor, Brad Pitt gave a shout out to "big, bad Bob Richardson," and while we wanted to follow up on that remark backstage, too, the sea of hands proved insurmountable, before Pitt returned to his seat.

"Designers - like DPs - just use one language - that is visual language."

- Ha-jun Lee, Production Designer of Oscar-winning Parasite

Perhaps the production designer of Parasite, Ha-jun Lee, winning the Art Directors Guild award for Contemporary Film Design, about a week prior to the Oscars, said it best when observing that designers - like DPs - "just use one language - that is visual language." Sadly, though, a further expounding on that language was missed when ADG bestowed its lifetime achievement award on designer Syd Mead, whose work on Blade Runner, along with director Ridley Scott and cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth, resulted, of course, in one of the greatest expressions of "visual language" in cinema history.

But, Mead, alas, passed away, at the end of December, so we never got to hear him expound on the fruitful vocation of being a "visual tourist," as described by director Denis Villeneuve, who presented the William Cameron Menzies Award to Mead's partner, Roger Servick. Mead, who worked not only in films, but on automobiles, video games, theme parks, brought "revolutionary designs" to his work, Villeneuve added.

Meanwhile, helping to guide not so much a revolution, as a reboot, is cinematographer Sarah Cawley, who has taken over the cinematic reins of the NBC drama Manifest, in which a planeful of passengers disappears for five years, only to suddenly return - not only having to integrate back into a world where they were all presumed dead, but dealing with strange manifestations that may be a kind of celestial insight, or "Calling," as it's, well, called - of how to make best use of their Second Chances, and perhaps prevent further tragedies.

"Season two," Cawley explains, "had a producing director (Joe Chappelle) who was new, so we did a kind of reboot with the look - we wanted to take the Callings in a more stylized direction."

While keeping the basic look of the sets, the Callings are a bit "smeary and blurred" on the perimeter of the shots, owing to "a Lensbaby - you take your regular lens off the camera. It's not exactly a tilt-shift lens, but it's similar." That allows them to shoot eyes (or sometimes ears, as "the Call"comes) to "make it more immersive - I think it helps the viewer."

Cawley was shooting primarily on "an ALEXA Mini with Panavision Primos - Panavision (in NY, where Cawley, and the show, are based) is very supportive. We had a number of special gear requests" - beyond the Lensbaby, for underwater shots, fire sequences, etc. - "and the supplier came through with them all."

LiteGear also came through with a 4x4 "LED unit with its own snap grid," which, she says, "really looks beautiful at the top of a shot, in addition to the time saved." Though the look they were going for, especially with exteriors, was more vintage than LED: "We had a number of locations that had existing sodium vapor streetlights - and some places we brought them with us. The world we created was New York City with sodium lights."

But it was back to LEDs, with nary a trace of sodium vapor in sight, at the one trade gathering we did make this month: The Digital Cinema Society had its annual lighting expo, held on the soundstage of IATSE 80 (the grips' local).

Like a miniaturized Cine Gear, but "lights only," though ARRI still had a table there, as did our friends at BB&S, currently awaiting parts from China so they can ship out some of their new lights, and Tiffen, the latter, with their Lowel line, and an emphasis on some of their own budget-priced LEDs.

But the main charm was the center area, where throughout the day, vendors could show and annotate - in live fashion - their latest gear, whether Fresnels from Mole Richardson, printed photographic backdrops from Rosco (the "matte painting" of the digital era), or more.

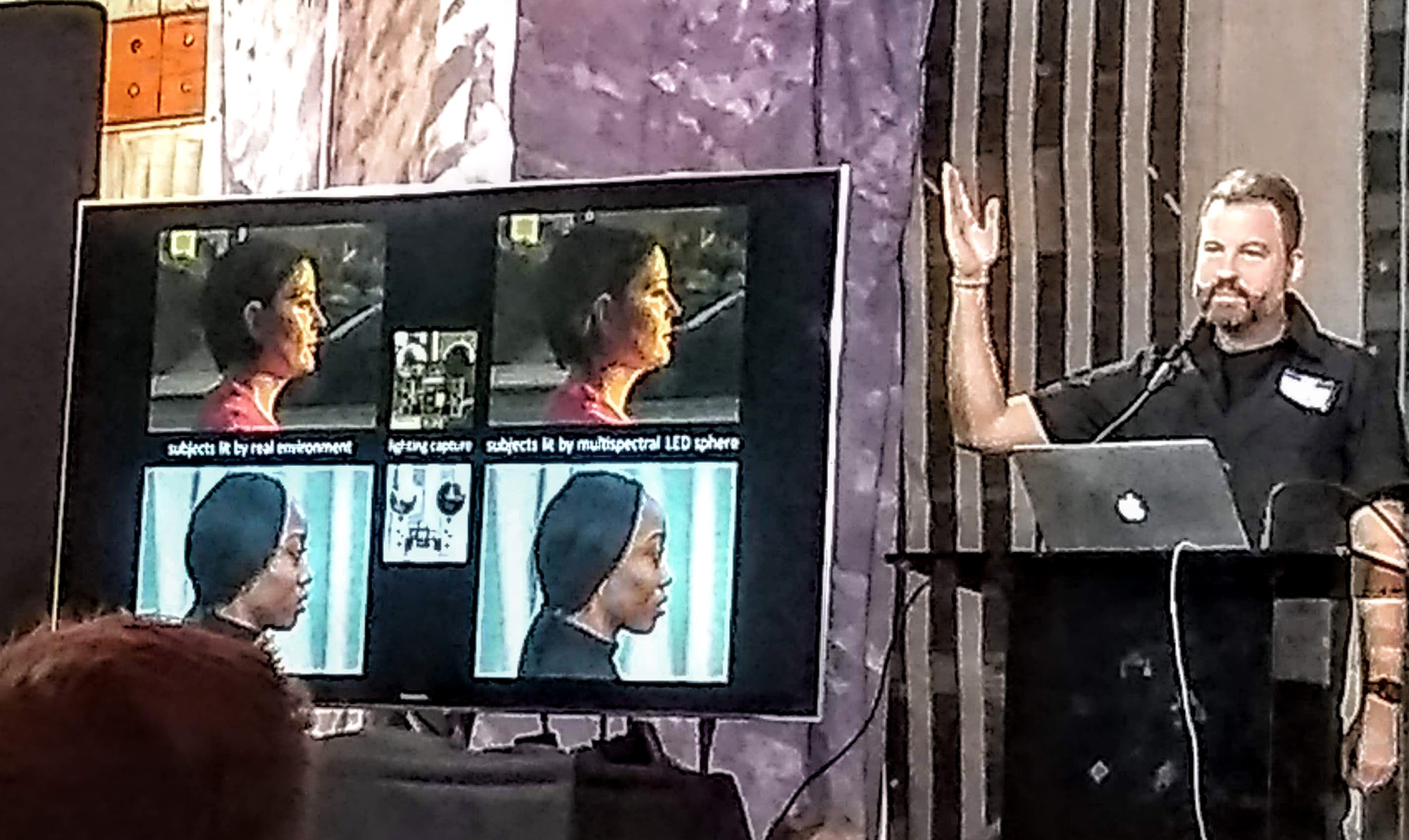

Somewhere between lunch time and a putative happy hour, there was also a panel, not quite "led" by Steven Poster ASC, since each panelist simply stood and presented, usually with slides, for about five minutes each. The topic was "SSI," or "Spectral Similarity Index," a tool that lets you know, as the VES' Paul Debevec (also a member of the Academy's Science & Technology Council) said, "whether light will do predictable things," even if - or especially when - you're changing set-ups, locales, and lighting sources.

One of the benefits of the digital age, then, as Poster later concluded, was these new tools-the products representing "remarkable light science," as he called it - allow for "repeatable and reportable color management systems."

We'll be reporting back here, on light both predictable and otherwise, in a month. In the meantime, drop a line: @TricksterInk or mlondonwmz@gmail.com