Consummate Filmmaker

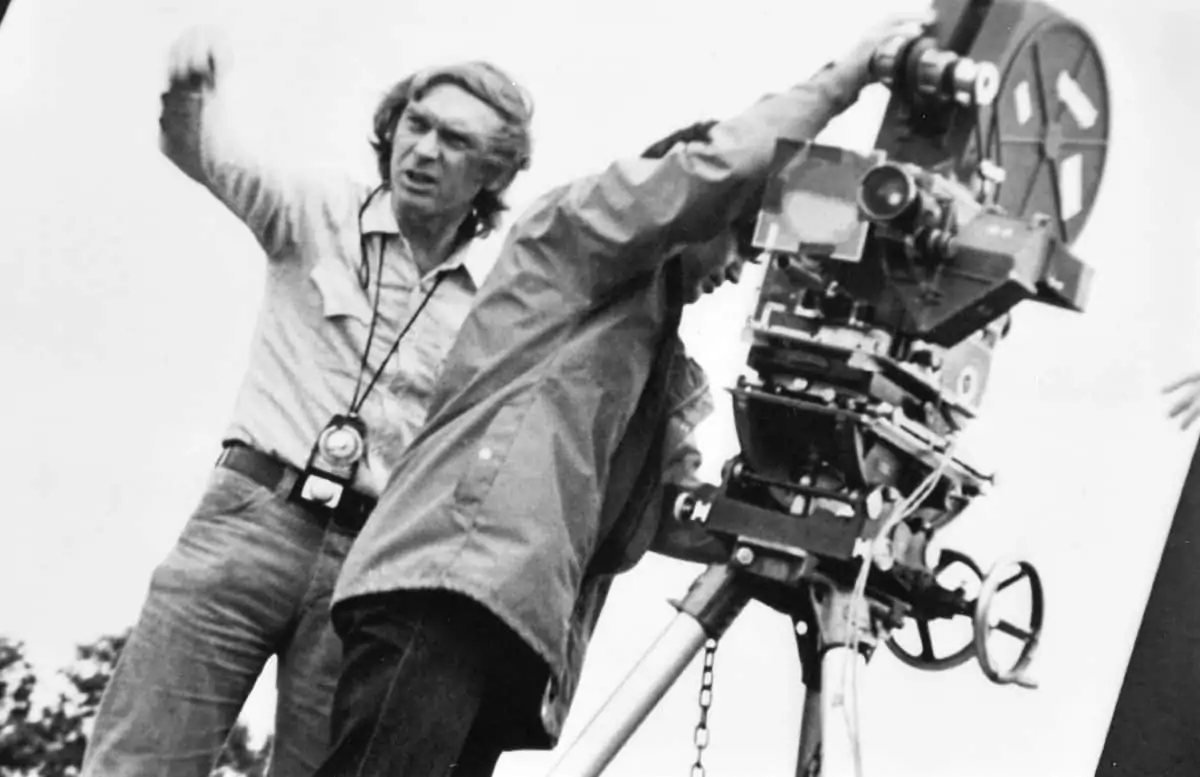

Clapperboard / Peter Macdonald BSC DGA

Consummate Filmmaker

Clapperboard / Peter Macdonald BSC DGA

BY: David A. Ellis

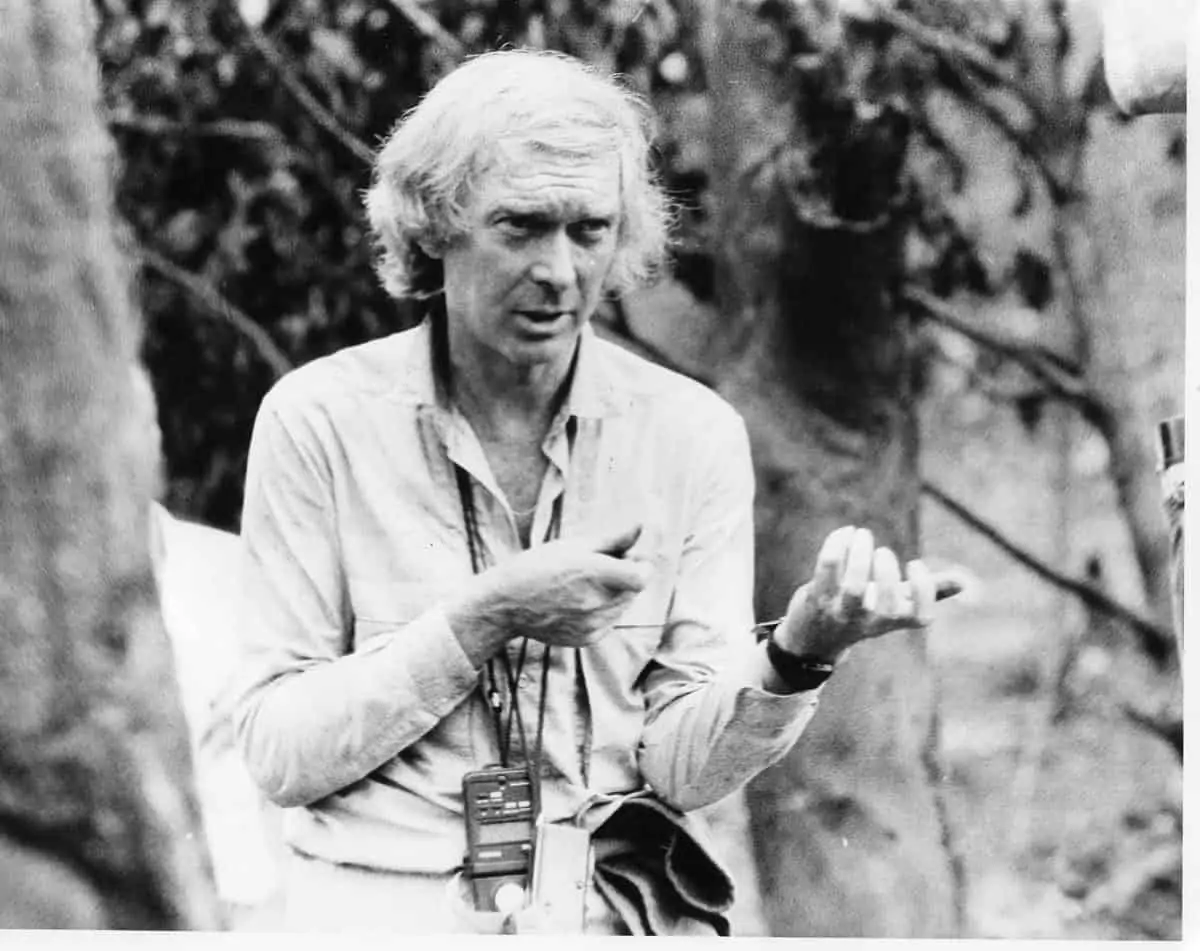

Notable cinematographer, director and producer Peter MacDonald BSC DGA was born in North West London in June 1939. He attended secondary school, leaving at fifteen. During a long a successful career in the movie production business MacDonald made many friends, one of whom, cinematographer Mike Brewster, worked with MacDonald on a number of movies including Harry Potter.

Speaking about MacDonald, Brewster said: “I first met Peter over thirty years ago on the second unit of The Empire Strikes Back. We have worked on many projects together and he became my friend and mentor. I have worked with many great and talented people, but I consider Peter to be the most consummate filmmaker of them all.”

What were your first memories?

My first memories were during WW2. They were fear, noise, smoke and a great uncertainty. Even as a five year old I realised it was serious. After the war, life was very grey and your playground was a bombsite.

When did cinema come into your life?

The cinema was for me and many others, during and after the war, escapism. It was an escape from reality – from a world that was hanging in rags. You saw films and believed them, even though later you found out it wasn’t true. America wasn’t full of heroic cowboys and Doris Days singing over a white picket fence.

How did you enter the film industry?

My first job was working for an Australian newspaper and, funnily enough, Mike Roberts, who became a camera operator, was in the same office. We both wrote to the cinema advertising company Pearl & Dean, and the following week we were both on the floor as clapper boys at Southhall Studios. It was there I met cinematographer Geoffrey Faithfull, who was head cameraman at the studio. He was a lovely man and one of my mentors. From there I went to Walton Studios to work on the TV series Robin Hood, followed by Sir Lancelot. During that period we were shooting Sir Lancelot in colour.

When did you first meet Geoffrey Unsworth BSC, with whom you worked a lot?

I met Geoff Unsworth for the first time on Night To Remember (1958). We were on the backlot at Pinewood. I did two or three weeks work on it. I started as a clapper boy. Then John Alcott BSC, who pulled focus, took some leave, so I took over as a very nervous focus puller. At that time I didn’t get to know Geoff or Johnny Alcott very well, but I was impressed with the calm way they worked. A little while later they were looking for a clapper boy. Clapper loader Ken Coles, who went on to become a cinematographer, recommended me. I did two or three films with Geoff as a clapper boy and then worked with him on Half A Sixpence (1967) as focus puller.

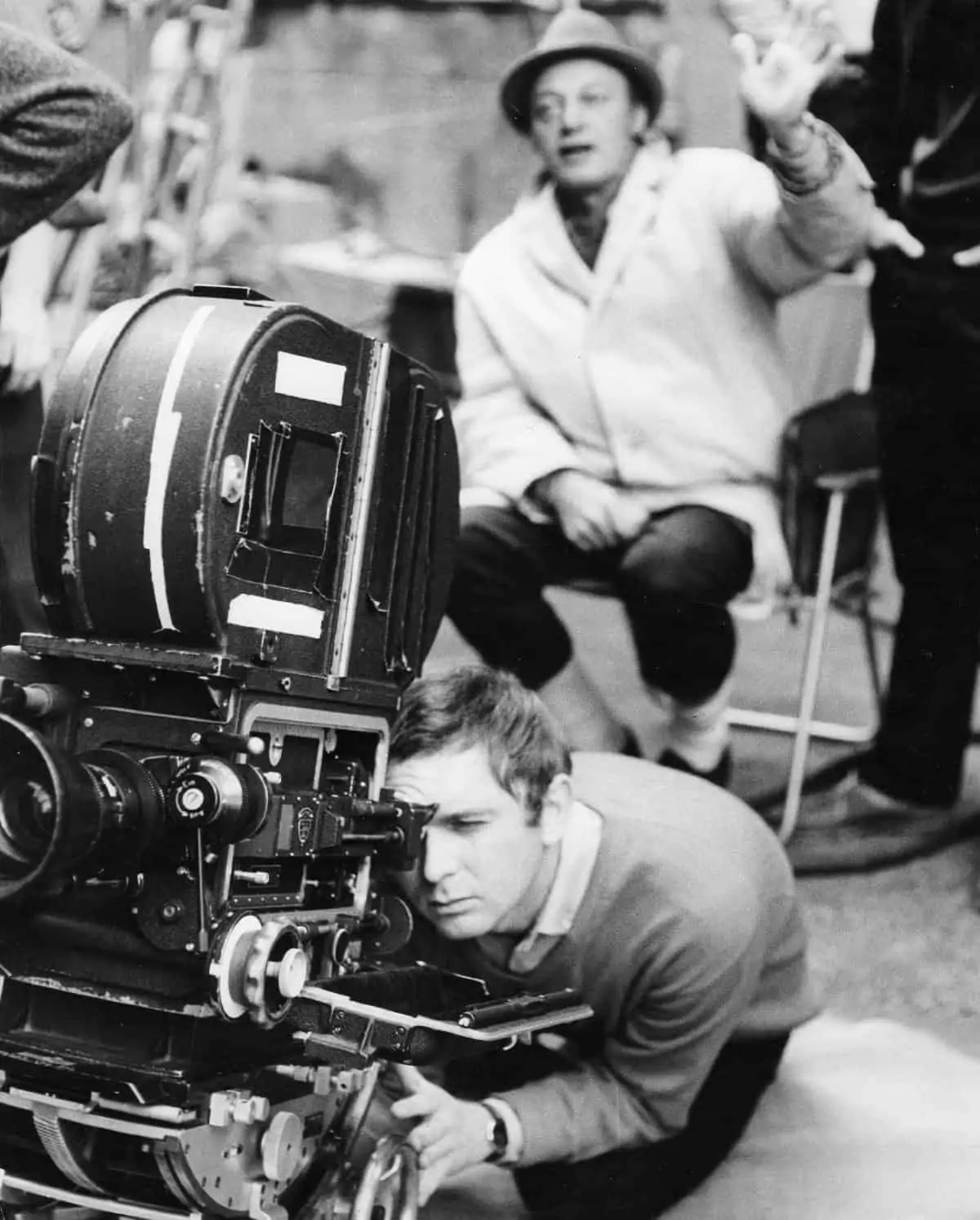

When did you become an operator?

I worked with Geoff on The Bliss Of Mrs Blossom (1968) as a focus puller. We got behind schedule and the director Joe McGrath and Geoff said we needed a permanent B-camera, so they gave me the job operating it. These were good times; the 10:1 zoom had just come out. It was the Sixties and anything was allowed. After that Jack Cardiff BSC contacted me to operate on Girl On A Motorcycle (1968). I was given a two-week trial. I guess I must have passed it and for the next few months we travelled Europe with a French and British crew.

What films stick in your memory?

Geoff Unsworth and I spent many years working together, which was a joy. Not only was he a great cameraman he was a beautiful person. I had John Campbell as focus puller and Frankie Batt as my dolly grip. We were just like a family. I guess the highlights at that time, filmwise, were A Bridge Too Far (1977) with director Richard Attenborough, Murder On The Orient Express (1974) with director Sidney Lumet, who was an incredibly good director, and Cabaret (1972) with Bob Fosse, who I regard as one of the best directors I have ever worked with. For that, Geoff won an Oscar and deservedly so. These were exciting days and you learned something different from each director. Funnily enough, I often felt that sometimes you learned more from a bad director because you learned how not to do it.

When did you get the opportunity to direct?

I was offered the job as second unit director/cameraman on Zulu Dawn (1979). David Tomblin was going to direct it with me. After the first day he said, “I think it’s better if there is only one director. You direct and I’ll organise and keep you out of trouble,” which he did. I then went on to direct the second unit on many films including The Empire Strikes Back (1980) Excaliber (1981) and Cry Freedom (1987).

You only did five films as a DP, when did you start?

My first DP offering was Secret Places (1984), directed by Zelda Barron. The film I am most proud of as a DP is Hamburger Hill (1987), the story of the Vietnam War, which we shot in a rain forest in The Philippines. Several years after its release I was in Washington at the memorial for the dead. I met some veterans and they said the film gave a truly realistic look of the war.

How did you get the job of main unit director on Rambo 3?

After my last film as a DP I got a call to go to Israel to work on the second unit of Rambo 3. I arrived on the day of shooting so knew nothing of the politics. I found out later that many people on the main unit were being sacked. Eventually the director, Russell Mulcahy, was fired. Because I had worked on Rambo 2, Sylvester Stallone suggested I take over the main unit as director. Looking back I would say working on it was the most difficult time I had in the business.

"On Cabaret the producers wanted a glossy Hollywood musical. Bob Fosse didn’t. He wanted a smoky atmospheric film that told the story."

- Peter Macdonald

Have you any industry heroes?

There is Geoffrey Unsworth BSC, who I always looked up to. David Watkin BSC in my opinion was the most original cameraman. He was very inventive, even though he pretended it didn’t matter. Alex Thomson BSC did wonderful work and I felt he never got the acclaim he deserved. Another is Australian Robert Krasker for his black and white work. Finally, I admire the American, Haskell Wexler. I have met him a few times and he is still enthusiastic and making films at 88. He made a documentary called Who Needs Sleep, which focusses on a young camera assistant, who was killed in his car after working long hours on the set.

Would you name some of the great directors you have enjoyed working with?

The top of my list is Bob Fosse. I loved working with Sydney Lumet, who was the most precise director I have ever met in my life. John Boorman was fantastic and Richard Donner was superb on Superman. Others include Tim Burton, Sir Laurence Olivier, Barbra Streisand and Alfonso Cuaron.

Would you tell us a little about the Harry Potter movies?

I worked on the first four Harry Potter films. They were very exciting and the digital world was taking off. For once we had enough money and time to make the magic work.

What are the best/worst moments on the set?

I think the best was on Cabaret because I had a very good working relationship with Bob Fosse who was very open to suggestions. In rushes he would say, “by the way that is Peter’s idea, not mine”. On Cabaret the producers wanted a glossy Hollywood musical. Bob Fosse didn’t. He wanted a smoky atmospheric film that told the story. He had helped reinvent the musical and I guess the Oscars proved who was right. My worst moment was on The Assassination Bureau (1969) with director Basil Dearden. Dearden said, “Ah the apprentice operator, there goes my schedule.” I thought the world was going to collapse on me.

What were the last two films you worked on?

They were Guardians Of The Galaxy and Johnny Depp in Mortdecai.

Finally what do you do away from working in the film world?

I enjoy classical and jazz music, travel, reading theatre and movies. I would like to add that I have many great memories of working on movies.