Shades of Grey

Phedon Papamichael ASC / Nebraska

Shades of Grey

Phedon Papamichael ASC / Nebraska

After three films together – Sideways, The Descendants and now Nebraska – Alexander Payne and Phedon Papamichael ASC share a working relationship built on intuition and instinct.

For their latest undertaking, the filmmakers journeyed to numerous tiny towns on the Great Plains of the US, including burgs in Montana, Wyoming, South Dakota and Nebraska, where Payne grew up and still maintains a home.

Papamichael brings a unique perspective to his work, having been born in Greece and raised there and in Munich before heading to the US and forging a cinematography career. Today, his credits include more than 50 narrative projects of astonishing range, including 3:10 To Yuma, Walk The Line, The Ides Of March, The Million Dollar Hotel, Knight And Day and the forthcoming The Monuments Men.

Nebraska brought Papamichael his fourth Golden Frog nomination at the Camerimage International Festival of the Art of Cinematography. Two-time Oscar winner Haskell Wexler ASC compared the film to an album of Ansel Adams photographs, saying of Papamichael, “Somehow, he even lit the skies!”

At the film’s centre is a curmudgeonly and doddering man, played by Bruce Dern, and his patient and somewhat aimless son, played by Will Forte. The old man believes in a sweepstakes con, that says he only needs to report to the head office in Lincoln, Nebraska to claim $1 million. His son agrees to accompany him, partly because he doesn’t have much better to do. Along the way, they visit the old man’s home town, where old, bitter conflicts are renewed. As is true in the entirety of Payne’s oeuvre, the tale is laced with a healthy dose of sharp-eyed comedy.

Payne and Papamichael made a bold decision to present Nebraska in austere B&W, with a 2.40:1 widescreen aspect ratio. Despite the audacity and persistence that was surely required to see this plan through, they both downplay the thought process that led to B&W, wary of over-analysing.

“Some photographs just look better in black and white,” says Papamichael. “Why should films be any different? Alexander and I saw this story in monochrome from the beginning, and my first job was to determine the best way to achieve that.”

During the testing phase, Papamichael performed side-by-side tests with ARRI Alexa, RED Epic, Eastman Double-X Negative Film 5222, Kodak Vision3 500T 5219 film stock with the colour removed in post. He eventually settled on a recipe that used ARRI Alexa cameras with film grain added in post. The images shot with 5222 film were used as a benchmark. Nebraska was one of the first feature films to use the Alexa’s anamorphic-to-4X3-chip capability.

Another important ingredient were older C-series Anamorphic lenses from Panavision, which had rehoused older glass, upgraded mechanics and improved consistency and sharpness.

“We were able to get a nice, film-like quality by using older lenses and adding grain,” says Papamichael. “The Alexa captured full-colour images, giving us extended low light capability – I wasn’t shooting on a 200ASA B&W film stock – and a good approximation of the final B&W image on set, which was a big help.”

"Some photographs just look better in black and white, why should films be any different?"

- Phedon Papamichael ASC

Papamichael’s crew included his longtime gaffer, Rafael Sanchez, and key grip, Ray Garcia. The A-camera operator was Jacques Haitkin, and the camera crew included Jeff Porter, Martin Moody and Steve Wolpa. The DIT was Lonny Danler, and the second unit team included director of photography Radan Popovic and Harry Zimmerman.

The Alexa’s sensitivity came in handy in the restaurants and bars Payne chose. The entire film was done at actual locations. Papamichael shot in them with little or no change in set dressing and only subtle lighting augmentations.

One particular scene that illustrates the filmmaking approach shows the family of Dern’s character as they pull up to a farmhouse and attempt to steal back a compressor that has been a sore spot for many years. As they drive away, it’s revealed that the compressor they have stolen is not the one in question. They attempt to return it to the barn, at which point the farmhouse’s family shows up. In keeping with the overall approach, the scene is blocked, shot and lit very simply.

“It’s precise, effective storytelling,” says Papamichael. “I think that scene could almost stand on its own as a short film. The audience is usually laughing throughout at the awkwardness. We composed the frame very carefully, and often allowed the actors to work within that frame. You can sense the desolate landscape at the edges of the frame. There’s no extraneous cutting. The lighting is almost all natural, available light. There’s an authenticity to the filmmaking that is in harmony with the setting and the story.”

The DI was done at Technicolor with Skip Nicholson, who was also intimately involved in the preproduction testing. “We used the DI to fine tune contrast and the grain level,” says Papamichael. “At one point, we brought in Paper Moon [1973; shot in B&W by Laszlo Kovacs, ASC] and compared the grain in that film print to what we were adding to our image. It was pretty close.

“We were also able to use colour correction on the full-colour image files to control some aspects of the image,” he says. “For night scenes, if an uncorrected HMI or 20K tungsten unit is providing a kick or atmosphere in the background, you can easily bring that up or down slightly without affecting the rest of the image, as long as it’s a particular colour. We didn’t do a lot of that, but it was a great tool to have.”

After Nebraska, Papamichael went to Europe to film The Monuments Men with director/star George Clooney, reprising their collaboration on The Ides Of March. For The Monuments Men, which follows World War II military men as they pursue stolen art treasures, Papamichael used a combination of film and digital, and shifted freely between anamorphic and spherical, using spherical master primes for wider shots, and using film for day exteriors and Alexa for low-light situations.

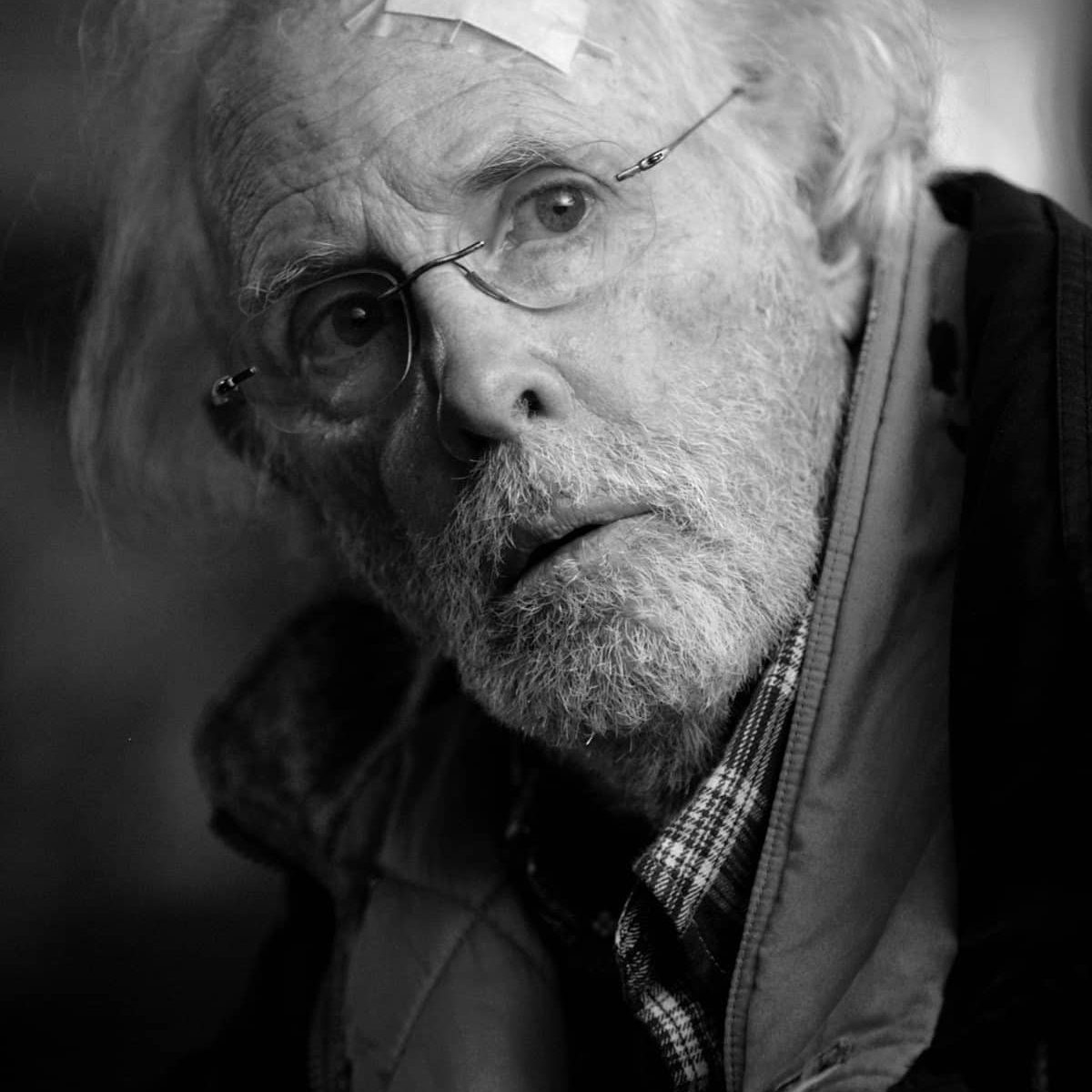

“The response to Nebraska has been very gratifying,” says Papamichael. “I love the kind of filmmaking that we do with Alexander. It’s a live process, something organic and human that starts as an unconscious, instinctual gathering of aesthetics, and becomes something that at its best, approaches art. Working with Bruce Dern was such a pleasure – the textures we captured in his face and his hair were ghostly at times. With the widescreen frame, we could shoot him in close-up and capture his humanity while maintaining the stark, powerful landscapes in the frame. And shooting B&W was fantastic – every cinematographer’s dream.”